It may sound strange, but in order to better understand the development of the art of Carlo Portelli (early 1500s - 1574), an artist who has never been to Rome to our knowledge, it is necessary to start precisely from Rome: in 1539 Francesco de’ Rossi returned from the Urbe, today known as the Salviati from the surname of the powerful cardinal who was his patron during his long stay in Rome, which lasted a good eight years. Salviati was returning from Rome with all the baggage of artistic and cultural experience he had accumulated during those years, and for Florence the painter’s return was probably one of the first opportunities for comparison with the results of Roman Mannerism, which Salviati began to make manifest in certain of his paintings produced in the 1640s: chief among these is perhaps the Charity preserved in the Uffizi Gallery. The relatively large number of paintings devoted to the theme of Charity that we also find in Carlo Portelli’s production should come as no surprise: in addition to being a theme that the artist clearly cared a great deal about, it was one of the most fashionable subjects in Florence at the time. All of Portelli’s paintings that deal with this theme are on display at the exhibition Carlo Portelli. Eccentric Painter between Rosso Fiorentino and Vasari, running at the Accademia Gallery in Florence until April 30, 2016.

|

| Paintings at the Carlo Portelli exhibition |

Returning for a moment to Salviati’s Charity, we said that it is a work steeped in Roman Mannerism: the pyramidal setting typical of Raphael’s Madonnas, the sense of solemn classicism also of Raphaelesque origin, the Michelangelo-like vigor, the strong light that makes the details shiny, the colorism of bright, vivid hues. The artist exerted a considerable fascination on Portelli, who made his own some of Salviati’s innovations to enrich his own highly original style, the result of a mixture of inspirations and personal flair that is probably unparalleled in all of Florentine Mannerism and shines with an unsuspected as well as surprising modernity.

|

| Francesco Salviati, Charity (c. 1543-1545; oil on panel, 156 x 122 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

The Charity of Casa Vasari in Arezzo, made around 1545, is Carlo Portelli’s first painting on the subject. The woman shows the typical characteristics of the allegory of this virtue, which would be precisely drawn up in 1593 by Cesare Ripa in his seminal Iconologia, the treatise that would be an invaluable source for the compositions of a great many painters from every corner of the globe. Thus, Charity is a “woman clothed in a red dress, who in her right hand holds a burning heart, and with her left embraces a child”: the red dress, the color of blood, symbolizes the sacrifice that “true Charity” can entail, while the burning heart and child emphasize “that Charity is a pure affection and ardent in the soul toward creatures.” Often the woman is depicted bare-breasted, nursing one of the children: for there is no gesture more charitable than feeding another creature. These are all traits we find in Portelli’s painting (who, however, in keeping with depictions more congenial to the taste of his time, painted small burning braziers instead of the burning heart).

Portelli used to alternate between paintings that reached very high levels of quality, with meticulous and precise finishing touches, and works whose outcome was not very happy in terms of mere pictorial quality: the Charity of the Casa Vasari falls into the second case. This does not mean that the painting is devoid of interest, because despite the fact that it is a work chronologically very close to the Salviatesque example, there are many elements that Carlo Portelli inserts following his own inclinations. Starting with the putti: unlike what was happening in Salviati (and in a great many other contemporary artists, even among the greatest), Portelli decides to characterize them individually, without paying too much attention to the fact that the putti, rather than angelic creatures, might resemble children who are not even too pretty (in fact: far from it). After all, Carlo Portelli’s goal was not the search for beauty: it was the search for artifice. Theelongation of the figures and their swirling arrangement, almost as if to create a spiral, should also be read in this key: these are expedients borrowed from the art of Rosso Fiorentino (1495 - 1540), Carlo Portelli’s most constant (and perhaps most authentic) point of reference throughout his career.

|

| Carlo Portelli, Charity (c. 1545; oil on panel, 110 x 82 cm; Arezzo, Casa Vasari) |

In fact, with fully Rossesque outcomes (although with the composition still indebted to Salviati) is the Charity preserved in Madrid, at the Prado: it is a painting of the 1950s whose attributional vicissitude has been anything but linear, since by tradition it has always been assigned to Giorgio Vasari until, in 1913, Hermann Voss first proposed the name of Carlo Portelli, accepted by almost all critics (Roberto Longhi was among those who expressed opposition). Compared to the Charity of the House of Vasari, we are dealing with a painting of quite a different quality, one that reaches such heights of refinement that we can place the work among Portelli’s most successful. And critics have always recognized this: even at the Florence exhibition it was presented as the highest example of Charity in the Valdarno painter’s production.

The complexions, following the example of Rosso Fiorentino’s art, become paler, and the expressions of the characters, in keeping with the refinement and even the taste for the bizarre that connoted Florentine Mannerism, become almost grotesque: this is the case of the putto that pops up behind the left shoulder of Charity, who offers us an indecipherable grimace, halfway between weeping and laughing. A small masterpiece of bizarre affectation. And, compared to the Charity of Casa Vasari, the proportions become even more elongated: just look at the sleeping putto occupying the entire bottom edge of the composition. The formal elegance of the painting is also evident from the scheme with which Portelli arranges the figures: the putti, in particular, are arranged around the Charity in a chiasm, that is, as if they were the arms of an imaginary X. Moreover, Portelli does not spare his skill and care in certain details executed with very high precision: this is the case of the jewels with which the Charity is adorned, or of the simple but refined relief decoration of the flaming urn embraced by the putto in the upper left.

|

| Carlo Portelli, Charity (c. 1550-1560; oil on panel, 151 x 115 cm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

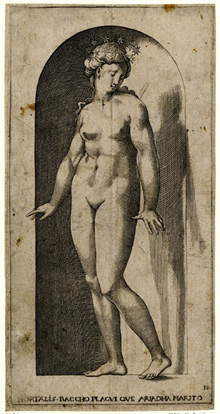

| Gian Jacopo Caraglio, Ariadne, based on a drawing by Rosso Fiorentino (1530; engraving on paper, 21.2 x 10.8 cm; London, British Museum) |

As we have anticipated, in Holland the work, dated to the late 1550s, has been juxtaposed with the French school of the time: the reference is to the school of Fontainebleau, the locality where Rosso Fiorentino moved in 1530, becoming court painter to Francis I. Rosso’s presence at Fontainebleau exerted a most notable influence on French painters, who immediately took him as an example because of the strong charge of novelty that the artist had brought with him to France. And he, in turn, renewed his own style: the strong imbalances and disorientation of his Florentine works began to be replaced by a greater preciosity combined with a certain monumentality and a more studied search for sophisticated solutions (evident especially in the use of cold lighting), although the basic nonconformist charge was not altered in any way. These are elements that began to manifest themselves in Rosso’s art as early as the late 1920s, during and after his stay in Rome, in which the Florentine artist had had the opportunity to come into direct contact with Roman art. Carlo Portelli had somehow managed to come into contact with these novelties: the most plausible hypothesis is that he had seen the etchings of Gian Jacopo Caraglio, taken from several of Rosso’s drawings. The figure of Charity would refer in particular to those that appear in the cycle of the Gods in the niches: Portelli’s Charity retains the statuesque grandeur and elongated forms typical of Rosso’s inventions. And furthermore, Portelli updates such inventions with the diaphanous coloring and cold colorism of the last Rosso, combining these features with strong chiaroscuro: striking are the sharp contrasts between the areas in light and those in shadow. All this contributes to the painting’s almost abstract, art deco ante litteram air.

|

| Carlo Portelli, Charity (c. 1555-1560; oil on panel, 126 x 78 cm; Maastricht, Bonnefantenmuseum) |

Not distinguished by the same charge of innovation, or even the same level of quality, is a late Charity, for which a date roughly between 1565 and 1570 has been proposed: however, the painter, having reached almost the end of his career, still has something to say and some original invention to offer. The painting is part of the collection of the small Museo del Bigallo in Florence, which collects the legacy of the Compagnia del Bigallo, an institution that, in the Florence of the time, provided assistance to the poor and needy. The theme of Charity therefore suited a painting to be donated, probably as an ex voto, to the Compagnia: this was probably the genesis of Carlo Portelli’s work.

A work in which we see again the red robe of Charity and the burning brazier: a return to tradition, in short. The cold chromatic range of the Maastricht painting is also abandoned in favor of coloristic solutions that have already been widely experimented with. Entirely new, however, is the affective outburst of Charity, who stretches out to affectionately embrace and kiss one of the accompanying putti. Portelli, however, in keeping with his own taste, avoids presenting us with a scene pregnant with intimism; on the contrary: the refinement of the composition still constitutes, and perhaps even more than ever before, a distinctive feature of his style. Because here Carlo Portelli experiments with an unprecedented structure: that is, he arranges the figures on the sides of an imaginary right-angled triangle, with the right angle at the bottom right, in correspondence with the child playing with the flaming urn, and arranged along almost the entire lower edge of the painting going to complete, with the mother’s foot, one of the sides of the triangle. The other consists of a vertical line on which Portelli arranges all the faces of the putti, and the triangle is closed by the mother’s body on the diagonal. And even if the characters have to assume unnatural and contrived poses to allow Carlo Portelli to draw his own geometric figure, patience: the purpose of his art is not the pursuit of naturalness. The little boy who appears on the left, who seems almost inserted with the sole purpose of filling the void that he necessarily had to create, is dressed in commoners’ clothes: he is probably a young man who has received assistance from the Compagnia del Bigallo.

|

| Carlo Portelli, Charity (c. 1560-1570; oil on canvas, 103.5 x 78 cm; Florence, Museo del Bigallo) |

Carlo Portelli’s artistic journey obviously does not end with these paintings, which nonetheless allow us to familiarize ourselves with some of the salient features of his style. Having the chance to see all these paintings, together, in a single exhibition and on the same wall, is an excellent opportunity to learn more about this extraordinary and original interpreter of Florentine Mannerism: lovers ofsixteenth-century art, and in general those who are fascinated by anintellectual and sophisticatedart, need only go to the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence until April 30, 2016 to see not only the paintings by Carlo Portelli we have mentioned in this article, but his almost complete production, gathered precisely for the Florentine exhibition.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.