To rediscover, at least visually, a painting that has been out of everyone’s sight for a good eleven years as a result of dramatic vicissitudes, is a great event: an event that needs to be shared with as many people as possible, in this case by showing some details of the canvas, still unpublished, during the restoration still underway in Kiev.

This is a wounded masterpiece, dramatically scarred by its negative history, wonderfully “naked.” I would like to convey feelings, giving everyone a chance to see how a great painting, though wounded in its greatest essence, color, can, at least I hope, convey some wonder. The painting is so beautiful and powerful that one cannot have the right to hide it from the world.

Of course, talking about yet another painting that is more or less attributable to Caravaggio may seem like a tedious and, above all, repetitive topic, given the large panorama of studies on new and old canvases by the master that “resurface” now cyclically in the debate among scholars. Therefore, I do not want to dwell on the history of this painting that has accompanied so much of my life (having dedicated all my work to it for three years) and that so many already know perfectly well; however, some hints are also necessary in order to place this work in the right space-time dimension. Of this Capture of Christ, which had been in Odessa since the early twentieth century, the whole story has not been written, in the sense that from the documentary point of view we have certain news of it only from 1868, when it appeared in Paris, for sale at the prestigious auction house in Rue Drouot No. 5, a time when it appeared to be owned by one of the most famous collectors of that time, Alexander Basilewsky. It was titled Le Baiser de Judas and was attributed to Caravaggio, being part of a sizable lot of artworks (mostly paintings) that Basilewsky decided to sell since in the meantime his interest as a collector had turned to another genre and historical period: the Christian Middle Ages, expressed in all its possible artistic forms. At that auction, however, the painting found no buyers or was even withdrawn from sale, perhaps because it had attracted the attentions of the brother of the future Tsar Alexander III, who had been able to admire it on his Paris visit the previous year. As to why the painting was not sold there is no certain information, what is known for sure is that Le Baiser of Judas was given by Basilewsky specifically to Grand Prince Vladimir Alexandrovich, who, by virtue of his great interest in art, shortly thereafter became president of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, in whose 1874 catalog it is found under number 264.

From then on the painting, confirmed in its attribution to Caravaggio, always remained in Russia first and in theSoviet Union then, in the various locations of the Odessa Museums, until the early 1890s when, after studies of the Mattei archives by the young Francesca Cappelletti and Laura Testa, news emerged of a Capture of Christ sold by the Matteis to William Hamilton Nisbet and also the receipt of a 1626 payment made to the otherwise unknown Giovanni d’Attili for a copy of the same work. International critics took a clear line, calling the Odessa canvas the copy commissioned by Asdrubale Mattei for 12 scudi, whereas the rediscovered canvas in Dublin (National Gallery of Ireland) with the same subject was considered the original, namely the one owned by Ciriaco Mattei painted in 1602 by Caravaggio for 125 scudi.

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ (early 17th century; oil on canvas, 134 x 172.5 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| Caravaggio, Capture of Christ (1602; oil on canvas, 133.5 x 169.5 cm; Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland) |

There will be an opportunity in the future to present the results of the research so far achieved through the careful analysis of the radiographic results, along with the rigorous sifting of the pigments used in the Odessa canvas, as well as the type of the canvas itself, data that already allow for a serious reconsideration of whether the painting could be the Mattei copy. The material used fits perfectly into the “Caravaggesque palette,” at least according to a study by Claudio Seccaroni(Some considerations on Caravaggio’spalette, in Caravaggio’s painting technique, “Kermesquaderni,” edited by Marco Ciatti and Brunetto Giovanni Brunetti, Nardini, Florence 2013): both the canvas and the colors used in the Odessa painting appear to be of far too expensive quality to justify the low amount of money paid for the copy, but we will certainly have occasion to return to this subject in more detail in the future.

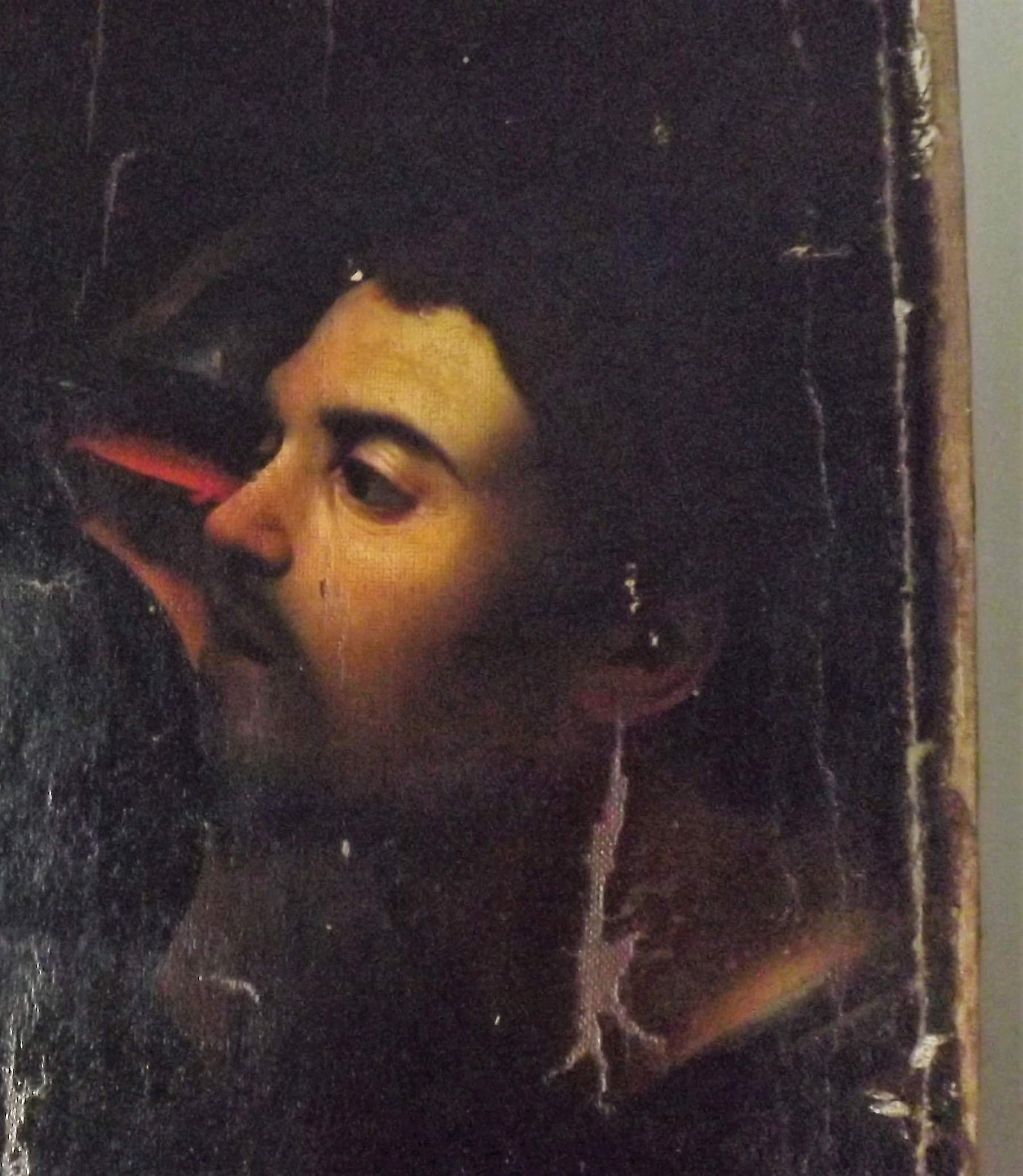

The real news comes from the analysis of the X-ray, which shows differences and afterthoughts usually unthinkable for a copyist who has before him the painting he is to reproduce. Not to mention, of course, the central figure: the Christ, who appears completely different from what the original should be while all the other figures are definitely the same. The figure of the Savior expresses other feelings than, for example, in the Dublin version: he is certainly full of holiness, sorrow, and perhaps even resigned and certainly aware of his fate, but he does not express a sense of helplessness in the face of what is to happen to him; on the contrary, he seems serene, in stark contrast to all the other figures in the composition, an expressiveness of the Redeemer that is not found in the other known versions.

Despite these incontrovertible basic considerations, the Capture of Christ in the Odessa Museum of Western and Oriental Art, long attributed to Caravaggio, had fallen substantially into oblivion after the discovery of the other version in Dublin. The new political and, above all, economic situation in Ukraine certainly did not allow the attribution of a painting, however prestigious, to be dealt with. It was only in 1998 that the canvas managed to cross the borders of its home country for the first time to be exhibited in Munich, then its exhibitions followed one another with some frequency in the following years, until the exhibition organized by Vittorio Sgarbi at the Palazzo Reale in Milan in 2005, when it was presented in the catalog with strong doubts about its “non-attribution” to Caravaggio. For the first time in many years, the term “replication” coined by Maurizio Marini found support, at least in raising the question of further verification on the work. The theft of Odessa’s The Capture of Christ in 2008, following its last exhibition in Düsseldorf (2006), no longer allowed opportunities for further research and verification. Immediately before the exhibition in Germany, in June 2006, the painting underwent a quick conservation restoration, with a careful and thorough radiographic and photographic examination, which, however, no one bothered to analyze, at least judging by the absence of documents in question: I was able to view all the files of that intervention which confirm the astonishing results already visible in the radiographs taken by the Grabar Restoration Center in Moscow between 1953 and 1955, and it is clear that we are not dealing with a trivial copy, almost certainly not the “famous” copy by Giovanni d’Attili, a painter about whom there is no other information. This was evidently known to the person who, perhaps, commissioned the otherwise unjustified theft, an operation that was not the most difficult but certainly daring given the considerable size of the canvas (134 by 172.5 cm) and its location. The episode continues to leave much puzzlement in the field, since the thieves did not at all consider (at least apparently) other paintings with “certain attributions” and certainly of great value such as, for example, the two Evangelists, St. Luke and St. Matthew, by Frans Hals, among others of a much more “transportable” size without having to cut the canvas (as was done) than a simple “copy” from Caravaggio.

|

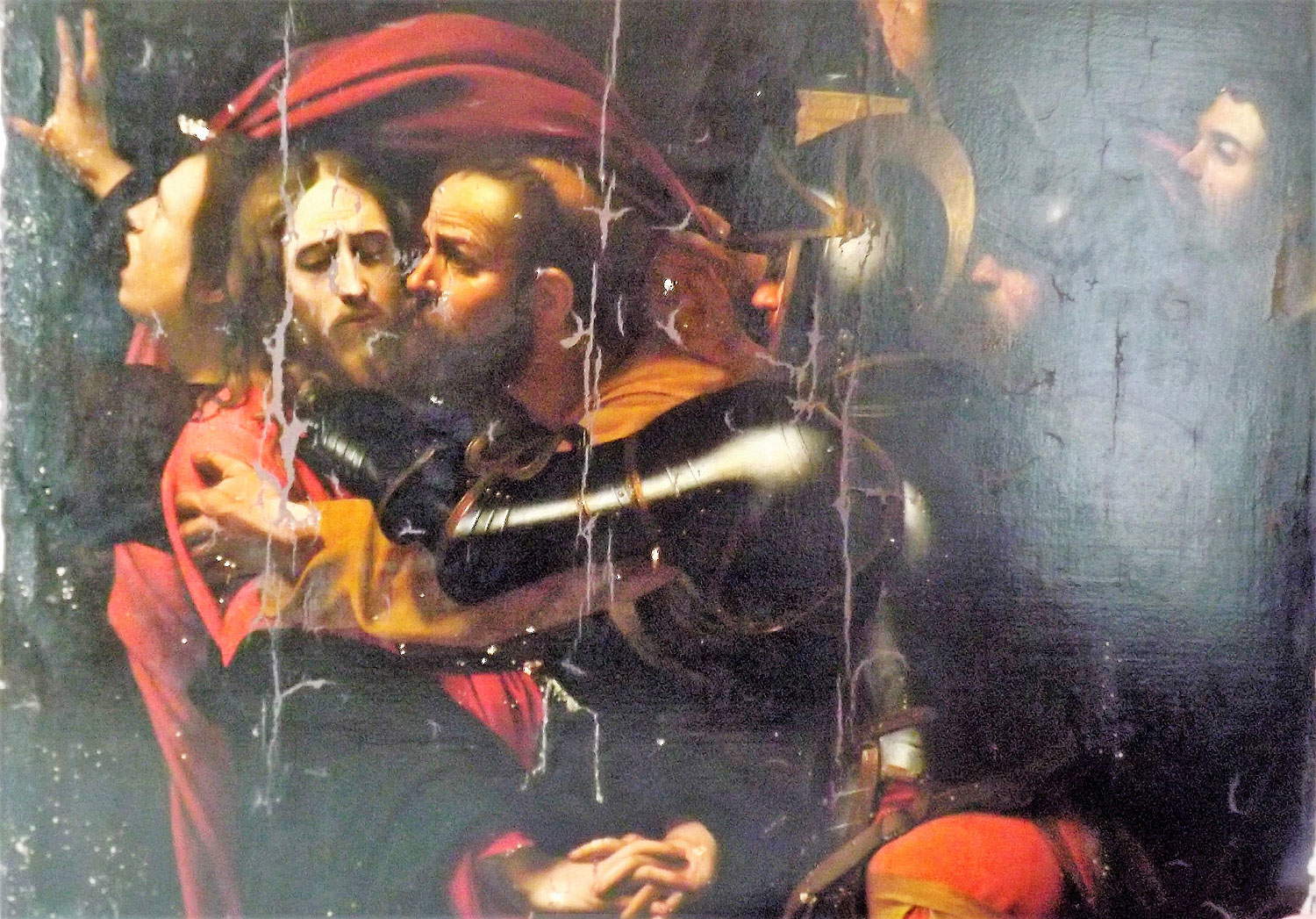

| Odessa’s The Capture of Christ during restoration. Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

| Odessa’s Capture ofChrist, detail of Judas’ kiss (during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

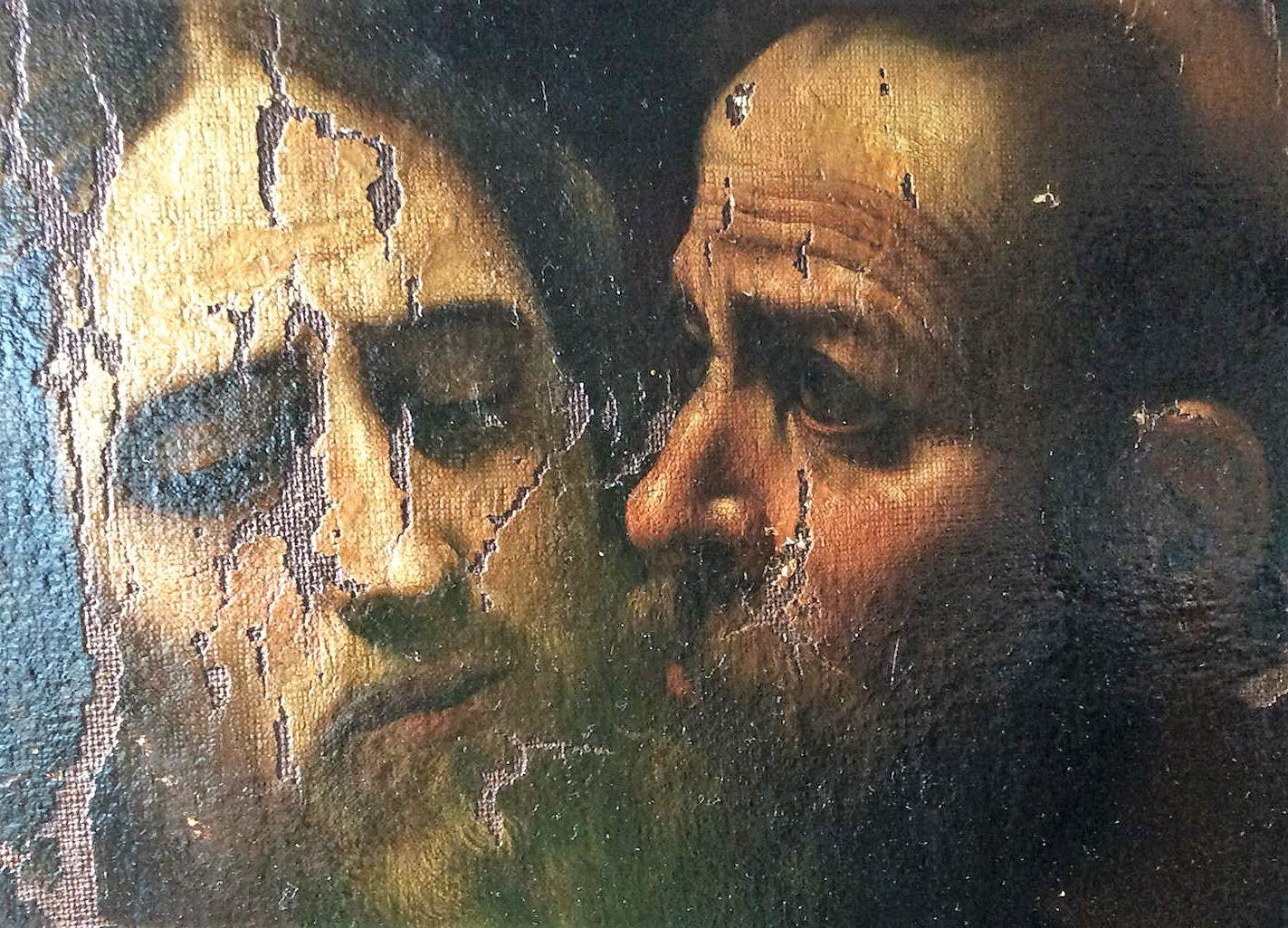

| Odessa’sCapture of Christ, detail with the faces of Christ and Judas (during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

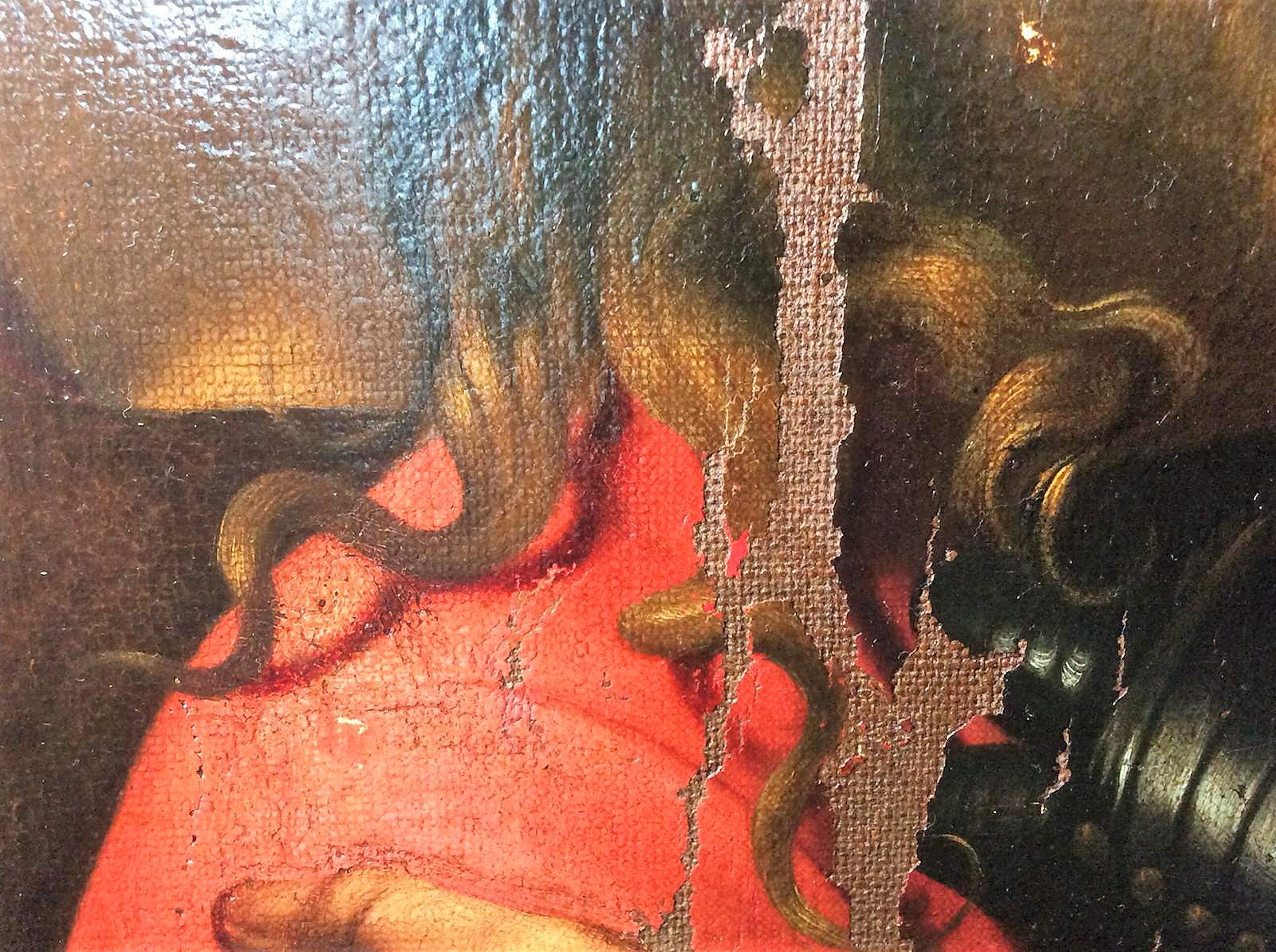

| Capture of Christ of Odessa, detail with Christ’s lock of hair (during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

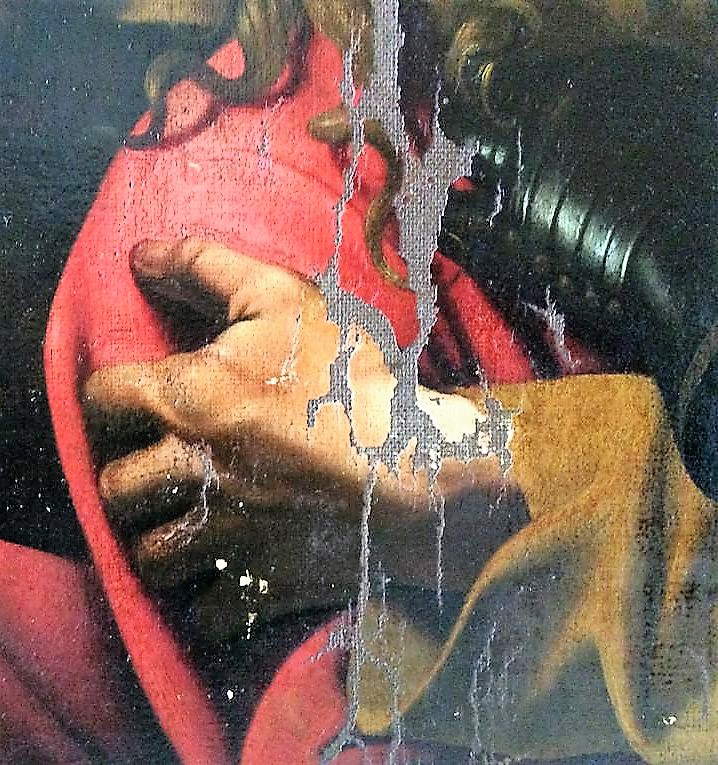

| Capture of Christ of Odessa, detail of Christ’s hands (during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

| Odessa’sCapture of Christ, detail of Judas’ hand (during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

| Capture of Christ of Odessa, detail of the servant’s hand(during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

| Odessa’sCapture of Christ, detail of the servant (during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

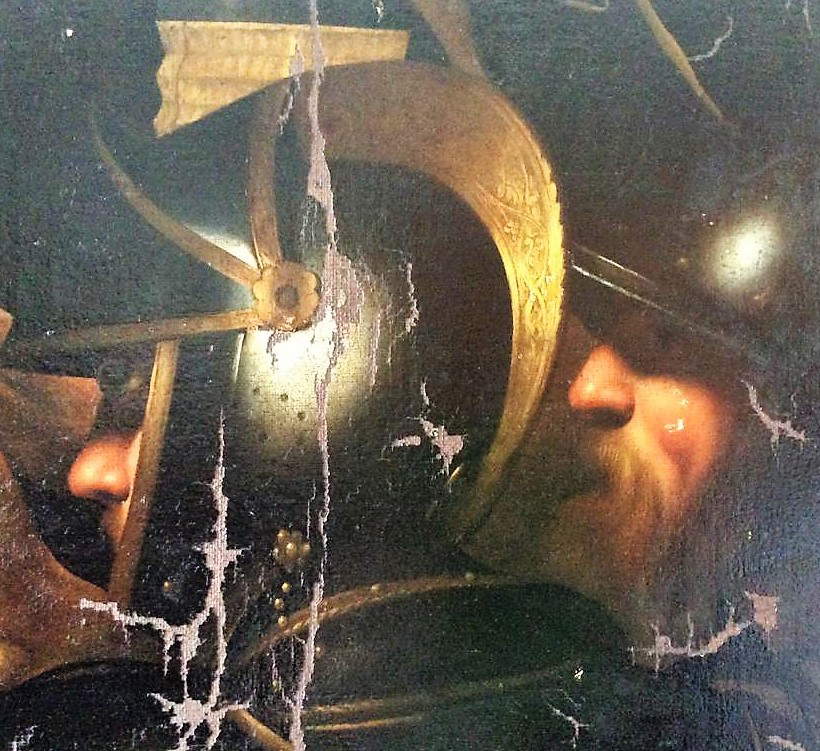

| Odessa’sCapture of Christ, detail of the soldiers (during restoration). Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

|

| Odessa’sCapture of Christ, detail of the upper left corner with brush strokes that could reproduce leaves. Ph. Credit Nataliia Chechykova |

But here we enter an affair that has all the characteristics of an international detective story and that has not yet found its final judicial solution, while the study of the work carried out by the writer, initially intended for the realization of a dissertation at theUniversity ofFerrara (rapporteur Francesca Cappelletti and co-rapporteur Giulia Silvia Ghia), later also found the interest of the heads of the Museum of Western and Oriental Art in Odessa, my hometown, of which this canvas has always been an admired and envied symbol. Thus, around the search so many people in Ukraine and Italy became enthusiastic, and great was the support of everyone, so much so that in the month of July just past, a meeting in Kiev with the Capture of Christ, finally live. Here is now deposited the painting under restoration, and the photos I attach to this brief report I believe may highlight not only the real artistic value of the work, “without makeup” and with all its wrinkles in evidence, but may perhaps also finally reopen the debate on the true author of the valuable canvas, which I do not believe can belong to the hand of the misunderstood d’Attili, as I will try to demonstrate shortly in a more detailed study.

*Many people have supported me in this research, starting with the already mentioned Francesca Cappelletti and Giulia Silvia Ghia. Therefore, I want to mention at least the director of the Odessa Museum, architect Igor Poronyk, and all the staff, especially art historian Ludmila Saulenko who first of all, as long as her illness allowed, guided me in the study with great fairness. And then I cannot forget with affection my friend Svitlana Stryelnikova, Director of the Ukrainian National Center for Research and Restoration, who opened to us her laboratories in which, despite the decidedly limited means available, her staff and specialists are doing excellent restoration work. The Judiciary of Ukraine, in particular the Podilsky District Court of Kyiv, granted permission to visit the painting during its restoration, showing, in full compliance with legal rules, a sensitivity and attention to such an important national asset as this Capture of Christ. Last but not least, I want to mention the cooperation of the whole “Italian group” and of the great and convinced friend of this painting, the Ambassador of Italy to Ukraine Davide La Cecilia.

The author of this article: Nataliia Chechykova

Storica dell'arte, Consulente per l’Arte Italiana del Museo di Odessa.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.