Kazimir Severinovič Malevič (Kiev, 1879 - Leningrad, 1935) was one of the leading Russian artists of the 20th century and is considered one of the pioneers ofgeometric abstractionism, one of the leading exponents of theRussian avant-garde, and the greatest artist of Suprematism (the Suprematist avant-garde was in fact founded by him in 1913). An artist who went through a historical period of great transformations and upheavals (including the October Revolution, which was destined to have a major impact on his art), Malevič invented an art completely detached from the natural world, as he was convinced that art’s task was not to imitate nature: consequently, he was convinced that the only possible language was that of total abstraction based on elementary geometric forms and essential colors. The artist himself defined Suprematism as “the dominance of art over the objectivity of real appearances. ”The new avant-garde was first theorized in 1915 in the manifesto of Suprematism written together with the poet Vladimir Majakovsky (and at the same time the first Suprematist works were presented to the public, in an exhibition in the city of Petrograd, today’s St. Petersburg), and then the concepts were further developed in 1920 in the essay Suprematism, or the World of Nonrepresentation.

According to Malevič, abstract art was superior to figurative art: hence the origin of the term “suprematism.” Indeed, the Kiev artist believed that figurative art was “a slave to nature,” so the goal of an artist’s research had to be theessence of art itself, which could only be reached through works based on pure forms and pure colors. The Suprematist experience was short-lived, as the newSoviet regime (theSoviet Union was born in 1922 after the dissolution of the Russian empire) focused on art with a strong social value (and this especially after Lenin’s death in 1924), thus incompatible with Malevič’s ideas. The artist moreover had relations with the German avant-garde, and given these ties he was also arrested and had to suffer the destruction of part of his notes. At the end of his existence, he had to resign himself and devote himself to figurative painting created, however, in accordance with his poetics of pure forms. However, his experience was fundamental to the development of further avant-gardes, such as the constructivist avant-garde, and the art of Malevič it also had some impact on design. “I came out of white, landed in white, and arrived in theabisso,” the artist declared, “here is suprematism. I put all the colors in the sack and tied a knot in it: here is the free white abyss, linfinite, they are before us.”

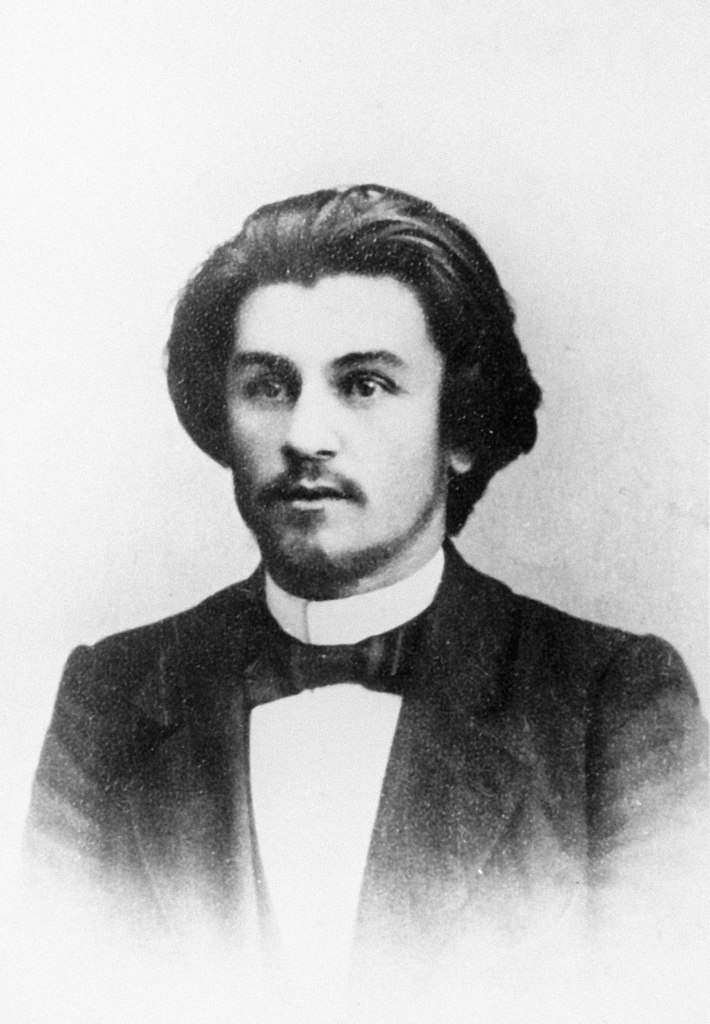

Kazimir Severinovič Malevič was born on Feb. 23, 1878, in Kiev to Severyn Malewicz, an agricultural technician, and Lyudwiga Alexandrowna: the artist’s parents were Poles who, after the January Uprising, that is, Poland’s rebellion against the Russian Empire in January 1863, moved from their native Poland to Kiev, which was then part of Russia. Malevič himself felt Ukrainian or Polish, although later in his life he denied any nationality. Because of constant relocations due to his father’s work, Malevič had a spotty education, although he managed to study at an agricultural school. He manifested, however, from an early age a marked aptitude for drawing. In 1896 the family moved to Kursk and the young Malevič found employment here as a technical draftsman, and in 1901 he married Kazimierza Sgleitz, also a Pole. The artist had tried to enroll in the Moscow Academy of Fine Arts but had to suffer the hostility of his family, especially his father, who was opposed to his son’s artistic passion. However, in 1904 Kazimir, having become independent, moved with his savings to Moscow and began studying at the local school of painting, sculpture, and architecture, starting in 1905. Fundamental for the artist was the viewing of Claude Monet ’s Rouen Cathedral in the collection of patron Sergei Ščukin, which provided the artist with a decisive contribution in the orientation of his art.

The artist participated in a public exhibition for the first time in 1907, when he exhibited twelve sketches in the fourteenth exhibition of the Moscow Artists’ Association, alongside other artists then little known but destined to become greats in art history, such as Vasily Kandinsky, Mikhail Larionov, and Nataliya Goncharova. In 1909 Malevič married on his second marriage to Sofija Rafalowitsch, and the following year, in December 1910, he participated in the first exhibition of the “Jack of Diamonds” (“Bubnovyi Valet” in Russian), a group of avant-gardists that included Larionov, Lyubov Popova, Moisey Feigin and other Russians, among others. The group’s goal was to update Russian art in the wake of the achievements of European art (these painters and sculptors looked mainly to the France of the Impressionists and Paul Cézanne). In 1912, after Larionov and Goncharova split, who felt that the Knave of Diamonds had become too Westernized, the pair founded the group “The Donkey Thing,” which Kazimir Malevi&ccaron also joined; joined, and exhibited at the first exhibition, also held in Moscow (the title of the group provocatively referred to the mockery of the critic Roland Dorgelès, who at the Salon des Indépendants had exhibited some paintings made by a donkey with its tail, presenting them as works executed by a fictitious Franco-Italian painter named Joachim-Raphaël Boronali). Malevič at the time had approached the avant-garde of Cubofuturism, but soon departed from it to found his own avant-garde, that of Suprematism. It was in 1913 that he created the work Victory over the Sun, which can be considered the debut of Suprematism, but the new avant-garde would not be formalized theoretically until two years later, in 1915, with the manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism. The New Pictorial Realism, with Black Square on the cover.

Malevič who in the meantime in 1914 had also presented some of his works at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, also organized his first exhibition in 1915, at the Dobyčina gallery in Petrograd, but received fierce criticism. In the meantime, the artist continued to work on his avant-garde, and in 1917, after the October Revolution, he obtained the post of supervisor of the Kremlin’s national art collections and also became chairman of the art section of the Moscow City Soviet, as well as a lecturer at the Petrograd State Art Laboratory. His painting had begun to make a name for himself right around the time of the revolution, so much so that in 1918 he and Michail Matjušin got a commission for some decorations in the Winter Palace. In 1919 the artist moved to Vitebsk at the invitation of Marc Chagall, who had founded a school of folk art in the city. In 1920 Malevič founded the “UNOVIS” group, the “Champions of the New Art,” and in the same year his daughter Una was born.

Malevič’s period of great activity continued with the launch of the 1922 Objekt magazine, which was created with the aim of bringing artists of different nationalities into dialogue. In 1922 all the artists active in Vitebsk moved to Petrograd, whereupon, in 1925, after the death of his second wife, Malevič married his third wife, Natalija Mančenko, but things had begun to turn bad for him: after Lenin’s death and the advent of the Stalinist era, the artist fell out of favor, as Stalin and his entire bureaucratic apparatus, unlike Lenin, rejected avant-garde art. The artist therefore found himself working as a teacher at the State Institute of Art History, and as soon as he could, in 1927, he left Russia on a visa so that he could travel to Germany, where he visited the Bauhaus and got to know the artists who belonged to the important school in Dessau. Returning to Russia and resuming his work at the Institute of Art History, he tried to revisit his theories to try to circulate them anyway despite the hostility of the Stalinist regime: his return to figurative painting, with Suprematist elements, is from this period. However, because of his foreign dealings, Malevič was arrested and interrogated by the KGB on charges of espionage, and subsequent threats of a death sentence. He was imprisoned for two weeks and released in early December. His art, meanwhile, was being fiercely mocked by regime critics, for whom Malevič s painting was a negation of all that was good and decent. Malevič thus found himself forced to return to the practice of realistic art. He found a job at the Russian Museum in Leningrad and remained there until his death on May 15, 1935 from cancer. After his death, there were no more public exhibitions of his work in the Soviet Union: his complete rehabilitation occurred only after perestroika, and the first comprehensive retrospective of his art took place only in 1988, in St. Petersburg.

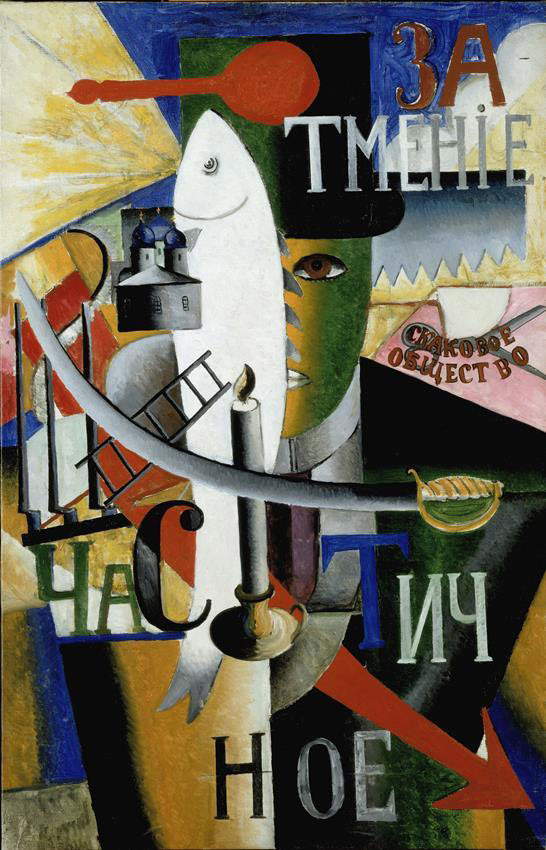

Malevič’s earliest works date from the early years of the twentieth century and are deeply influenced by the French art of those years: the artist, in particular, looked toImpressionism and French painting in general (his models of reference were Monet and Cézanne, but he also worked by looking to Symbolism and Pointillism, as well as Russian folk art and the country’s figurative tradition: the strong schematization refers precisely to the traditional art of the Russian) and proposed a painting still with a figurativist stamp. In the early 1910s his interests veered toward Cubism and Cubofuturism, so much so that in this period works characterized by two-dimensional forms and simplified colors predominate, but the look at reality is not yet abandoned, for it is still portraits or scenes of everyday life that are represented by the artist according to the canons of the Cubofuturist avant-garde. Figures are thus reduced to shapes such as cones, spheres and cylinders (e.g. Office and Room of 1913 or Englishman in Moscow of 1914, where some words are also inserted, as is typical of Cubofuturist art), already hinting in this an interest in reducing to the essential. The masterpiece of this phase is undoubtedly The Grinder, a work in which the protagonist is broken down according to the dictates of Cubism, but in a manner that does not shy away from also conveying the sense of movement rendered through sequences of identical juxtaposed forms.

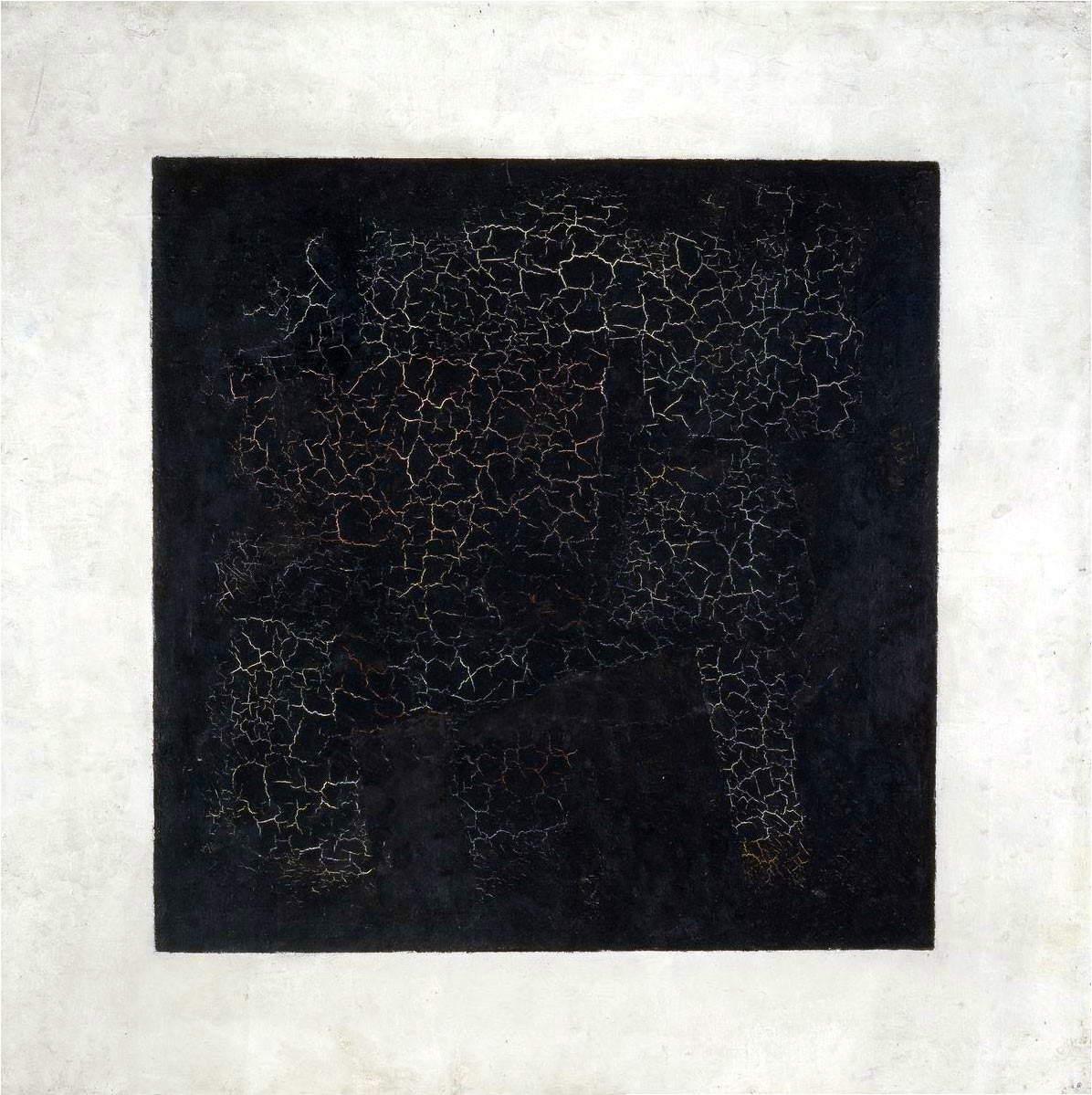

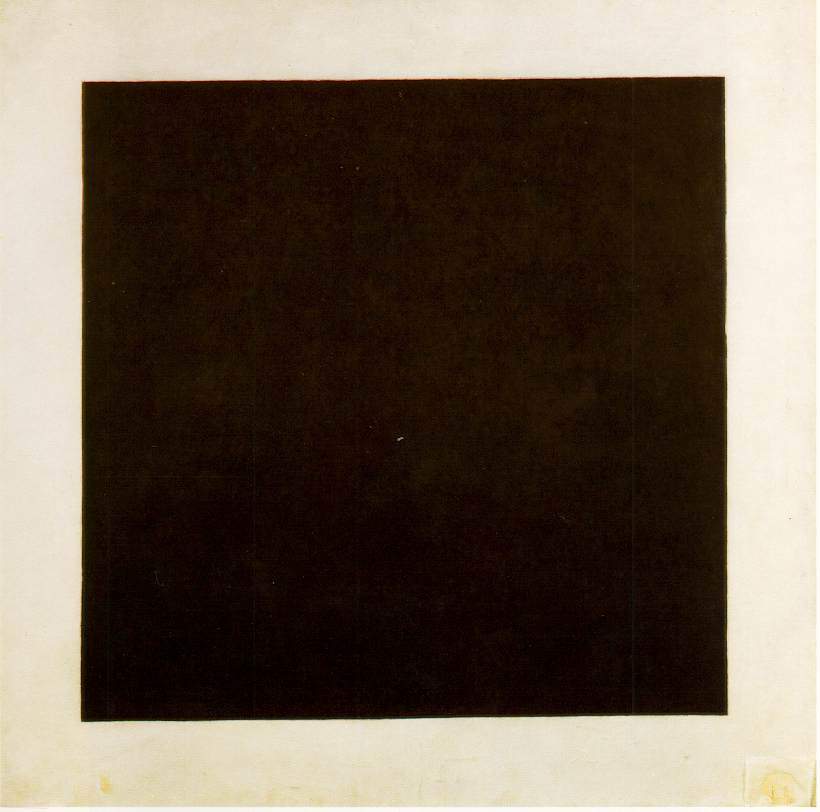

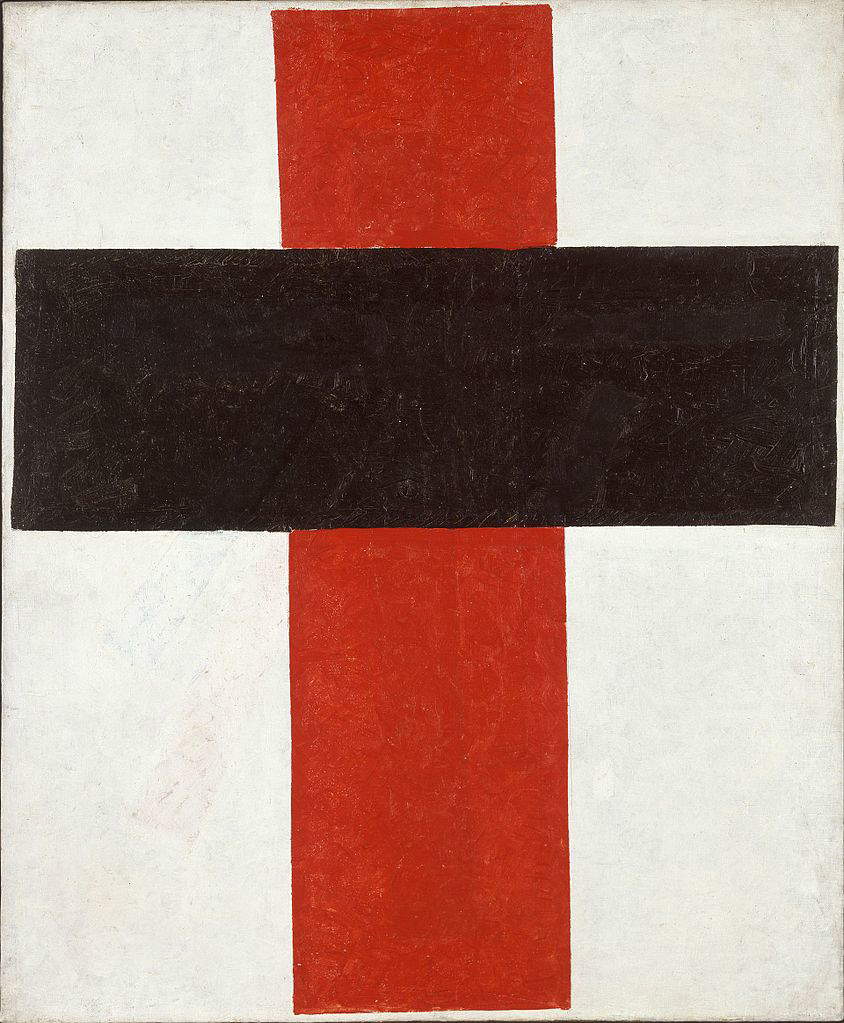

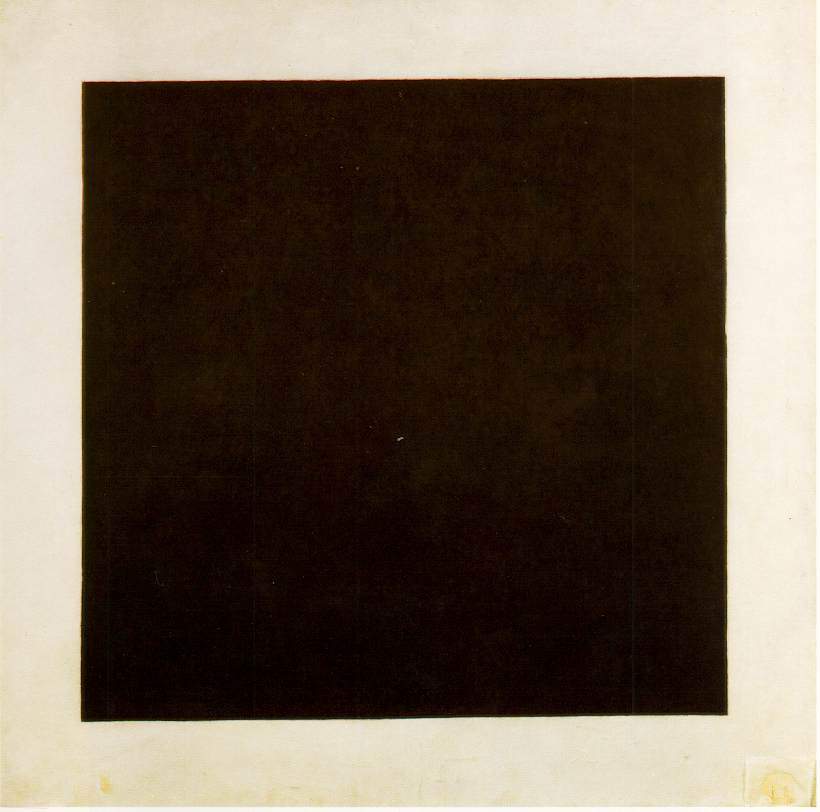

An invention of the Malevič cubofuturist are the so-called “alogical” compositions, a term he coined for his assemblages of geometric figures, words, and reproductions of works of art such as the Mona Lisa. Famous in this sense is the Composition with Mona Lisa of 1914 kept at the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg: in this painting we already find some of the elements that will be the basis of Suprematist poetics, such as squares of pure color. Malevič s art changes radically after the writing of the manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism, a work in which Suprematism is defined as the “supremacy of pure sensibility in the figurative arts.”Abstraction, for Malevič is thus the supreme schematization of forms leading to “pure expression without representation.” Symbolic of this poetics is the celebrated Black Square on a White Ground of 1915, now preserved at the Tret’jakov State Gallery in Moscow. According to the artist, only pure forms (the square, rectangle, circle) and pure colors (black and white, blue, red and yellow) are able to express the essence of art. This language also nurtures the aspiration to become autonomous from experience and thus to become universal. Also from 1915 is the painting Red Square. Pictorial Realism of a Peasant Girl in Two Dimensions, where a red square on a white background is the protagonist. “We, the Suprematists,” he had to write in the text accompanying the first Suprematist exhibition, that of 1915, “open the way for you. Make haste! For tomorrow you will no longer recognize us.” Not only that: the artist had also presented himself with a certain polemical streak (“I turned into the zero of forms and pulled myself out of the junk of academic art,” the painter wrote).

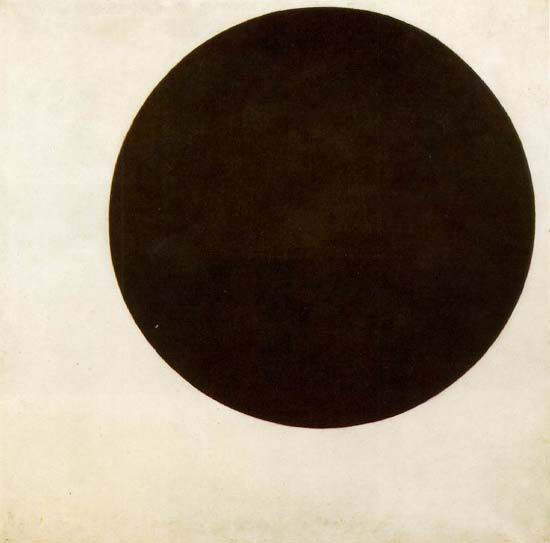

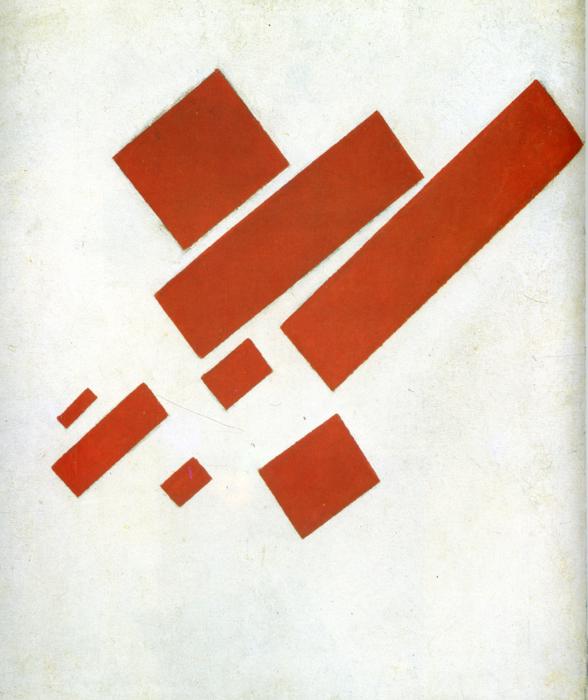

Two tendencies can be detected in Malevič suprematism: the first is the so-called “of the squares,” the second is the “cosmic,” with compositions such as Eight Rectangles from 1915 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, for which works are painted that respond to the artist’s idea that the new suprematist art form is also suitable for expressing humanity’s tension toward the cosmos. Art was for Malevič a tool to elevate humanity.

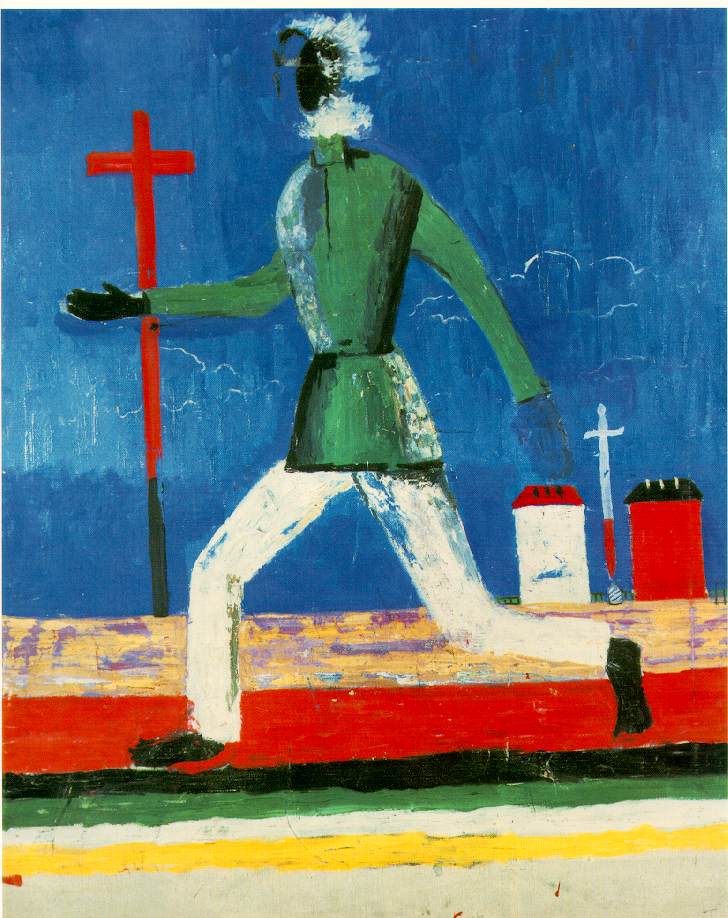

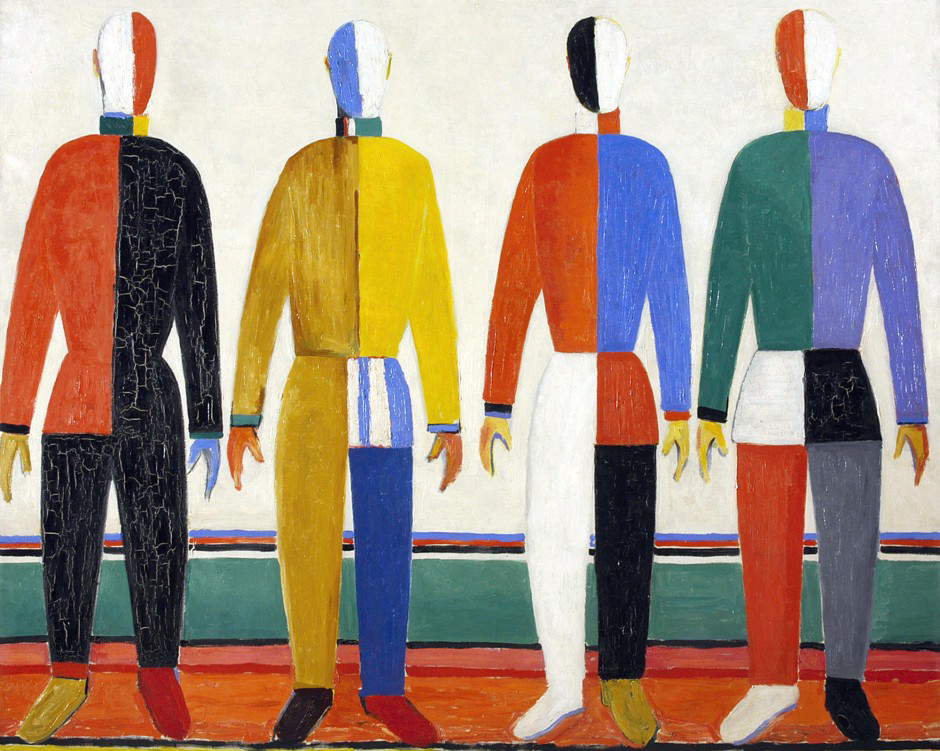

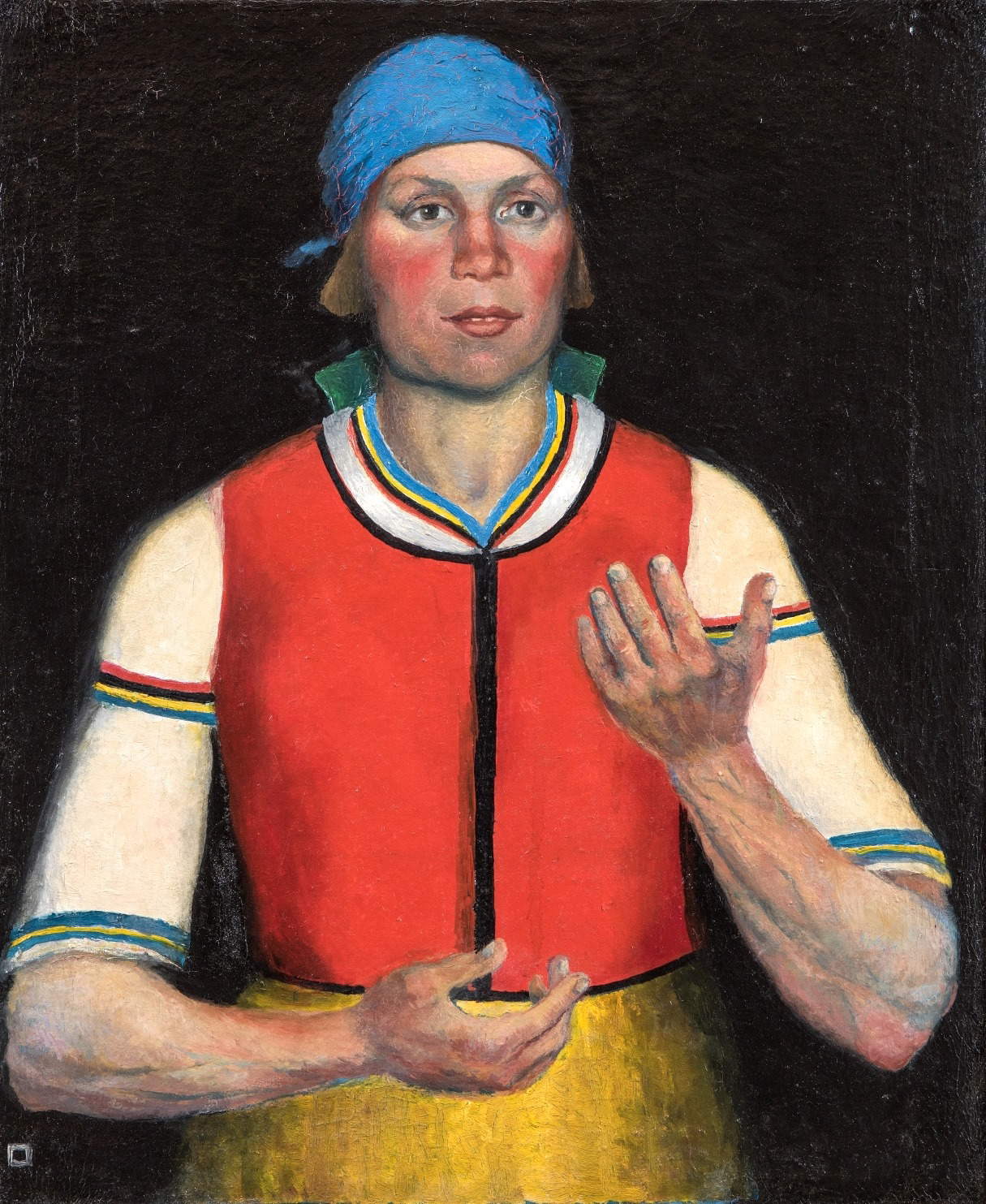

For the rest of the 1910s and the early 1920s, Malevič continued to create Suprematist works, but he had to radically modify his art after the death of Lenin and the rise of Stalin. Malevič was in fact forced to return to figurative art in order to continue working, and he invented images whose protagonists were the so-called “Budetljanje” (“those who will be”), faceless figurines without individual connotations that were meant to represent the Russian peasant world and people. Even these works, however, were not looked upon favorably, so the works of the extreme phase of Malevi&ccaron’s career; mark a return to a naturalist painting (the 1933Workwoman and The Artist’s Wife of 1933-1934), where the only concession to the avant-garde that was are the pure colors used for the clothes.

The main works of Kazimir Malevič are located outside Italy, and particularly in Russia. The main nucleus is at the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg where the main masterpieces of the Suprematist period, such as Red Square, Black Square, Black Circle, and Black Cross, are located. Many of the Cubofuturist paintings from the early 1910s, on the other hand, can be found at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, which houses one of the world’s most important nuclei of Malevič’s works, the largest outside Russia (in fact, the Dutch institute was the first European museum to promote the Kiev artist’s work). Notable works by Malevič can also be found at the Tret’jakov Gallery in Moscow (second only to the Russian State Museum in terms of the importance of the nucleus of Malevič’s works in Russia), the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, MoMA in New York, and the Ludwig Museum in Cologne.

In Italy, the only important work by Malevič (an Untitled painting from 1916) is kept at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. A major retrospective exhibition of the artist was held at GAMeC in Bergamo from Oct. 2, 2015 and Jan. 24, 2016, with works from Russia and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam: never before had such a significant nucleus of works by Malevič arrived in Italy. Since the works of the great founder of Suprematism are practically absent in Italy, to see them in our country one has only to wait for temporary exhibitions.

|

| Kazimir Malevič: life and works of the founder of Suprematism |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.