The School of Barbizon was a French painting experience at the turn of the first and second halves of the 19th century, a current in a broader European art movement that tended toward the affirmation of naturalism in art, and which made a significant contribution to the establishment of French 19th-century Realism.

It was a loose association of artists who worked in the village of Barbizon, located just outside Paris near the Forest of Fontainebleau between the 1830s and 1870s. The members of the School had different interests and artistic styles, but they mainly focused on landscapes and outdoor painting, with a common desire to elevate this pictorial genre from the background of classical scenes to a subject in its own right. The countryside and the ancient trees of the forest, as well as the workers in the fields around, exerted a strong attraction of rediscovering natural beauty away from the city, inspiring several generations of artists.

The Forest of Fontainebleau began to attract artists as early as the 18th century, including neoclassicists Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld, Théodore Caruelle d’Aligny, and Alexandre Desgoffe. The painters were attracted not only by the wild and varied landscape, but also by French fables and legends related to the forest. It was, however, the arrival in the early 19th century of Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (Paris, 1796 - 1875) and Théodore Rousseau (Paris, 1812 - Barbizon, 1867), who moved there permanently in 1846, that made the area a magnet for other artists. First and foremost, Jean-François Millet (Gréville-Hague, 1814 - Barbizon, 1875), who went to live in Barbizon with his family in 1849 to escape the political and social turmoil of the capital and who there died there, along with Charles-François Daubigny, Jules Dupré, Narcisse-Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, Constant Troyon and Charles Jacque, among others.

In the early 1820s, Corot began sketching and painting landscapes around Fontainebleau. Although he never actually lived in the area, he also returned there frequently in 1829 and 1830 and was an influential and active supporter of other Barbizon artists. In the early 1830s, the development of the railroad system from Paris made easy travel to Barbizon possible, and the opening of the inn, “Auberge Ganne,” ensured that artists had a place to live, work, and share ideas and modes of painting.

From 1833 Rousseau began to stay in Barbizon for long periods, in which he would explore the environment by engaging in sketching and painting outdoors. His passion for the forest and landscape made him a natural leader of the group and attracted other artists there, united in pictorial excursions and influenced by his practice and motivations. In the following decades, the village of Barbizon and its environs became a primary artistic destination, particularly during the uprisings of 1848 that caused many Parisian artists to flee to the seemingly safer countryside. Hundreds of paintings and photographs were made during this period, depicting the area and its rural life.

In the eighteenth-century neoclassical tradition, landscape painting was considered relevant only if it was presented in an idealized style and as the backdrop of an academically supported historical or classical narrative. In the early nineteenth century there was growing enthusiasm on the part of young pupils for a new, more realistic rendering, not tied to the historical landscape, but to the vision and study of detail, as had been the case with the Dutch painters of the seventeenth century. At the same time, a number of others were beginning to draw outdoors around Paris.

In reaction to the stylized and idealized representations of figures and landscapes of neoclassicism, most Barbizon artists approached painting naturalistically, capturing the scenery they saw truthfully, making careful observations and painting outdoors to faithfully reproduce the colors and shapes of the countryside. Although many of their works feature figures, most of them are untethered from a narrative. Indeed, it was intended to assert that the actual landscape itself constituted the main subject of the work. The exception to this view was Millet, who extended the concepts of naturalism to the human form, focusing on workers in the rural area around the village, often including social commentary in his art.

At the same time, in the first half of the nineteenth century, themes of Romanticism were spreading in Europe, and in France, which seem to have influenced some Barbizon painters. In many countries, Romantic painters were turning their attention to nature and outdoor painting in works based on close observation of the landscape, sky, and atmosphere. Some artists emphasizing humans as one with nature, others depicting the power and unpredictability of nature over humans, in each case devoting themselves to depicting the subjective reaction, the inner life in relation to the surrounding nature. This influence on the Barbizon group can be traced to the work of British artist John Constable (East Bergholt, 1776 - London, 1837), whose landscapes combined a naturalistic treatment, based on careful observation, with a Romantic sensibility.Constable’s work was first exhibited in Paris in 1824, and members of the Barbizon School drew inspiration from his naturalistic dedication, broad brushstrokes and loose style in contrast to the traditions of Salon and academic painting.

The so-called Barbisonniers, Barbizon painters, developed Constable’s freedom of brushwork, experimenting with various techniques including applying multiple layers of paint over other paint that was still wet, and then completing a canvas in one sitting, and collectively focused on the effects of sunlight on nature. Many worked affirming the use of loose brushstrokes and a personal style, unlike traditional academic painting. All of these artists, despite their partly romantic inspiration, emphasized the simple and ordinary rather than the terrifying and monumental aspects of nature. These experiments had a profound impact on the later work of the Impressionists. Unlike their English landscape contemporaries, they had little interest in transient effects and atmospheric variations, emphasizing instead permanent features, painting solid, detailed forms in a limited range of colors.

Each Barbizon painter had his own style and specific interests. Corot became famous with works suited to official taste, but he found his most authentic path by painting landscapes in secret, constructed firmly for broad masses of color, captured from life and at the same time interpreted through his own sensibility. “No one taught me,” he wrote, “my instinct drives me and I obey it,” revolutionizing the obsequious technical attitude of his contemporaries. The revelation, which led him to be among the leading French landscape painters of the 19th century, came to him in his travels to Italy in discovering the Mediterranean light, and then as he continued to move around France in search of ever new subjects.

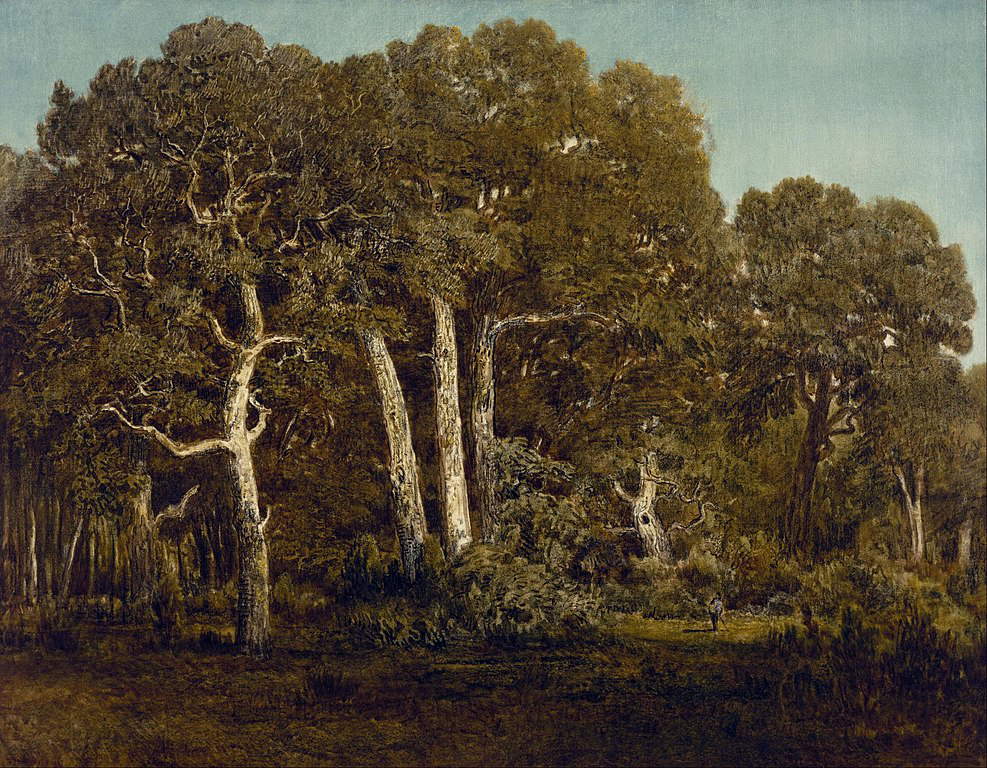

Barbizon’s leader, Rousseau, focused on views of vast expanses and intricate looming trees, combining objective naturalism and his own artistic subjectivity to bring out a majestic and mysterious landscape painting, achieved mostly with small, highly textured brushstrokes. In scenes such as The Great Oaks of Bas-Bréau (1864), one senses how for the painter, and others in the group, the figure of man was easily overlooked, suggesting human presence as minor among the ancient trees.

The most detailed and close-up scenes were those chosen by Dupré, who tended to express the movements of nature. And while Daubigny favored lush greenery and images of quiet contemplation and harmony, Díaz de la Peña mostly painted the dark forest of Fontainebleau from within, mottled by the sun. Troyon and Jacque devoted themselves mostly to placid scenes with livestock.

Millet, the only major painter of the group for whom the exclusivity of pure landscape was not important, made paintings of peasants at work that celebrate the nobility of daily, working life in the fields. Rather than depicting forest scenes, Millet was attracted to the plains stretching from Barbizon to Chailly, where he observed groups of intent workers, introducing to a theme dear to Realism, the depiction of the social conditions of the humble. His painting The Gleaners (1857) is iconic. At Barbizon, Rousseau and Millet were close friends and developed their own styles, respectively.

After suffering for some time from a total lack of recognition, the Barbizon painters began to gain popularity beyond mid-century. Most of them gained official recognition from the Académie des Beaux-Arts and great prizes for some paintings; but it was at the end of the nineteenth century that their School was particularly appreciated. The historical importance of the group was instrumental in establishing landscape painting, pure and objective but free from classical conditioning, as a legitimate and appreciated genre.

|

| The School of Barbizon, the French landscape painters of the nineteenth century. Themes and styles |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.