Two large monumental tanks, a cult building probably dedicated to Hercules and an articulated funerary complex from the Republican age: these are the latest discoveries of preventive archaeology excavations conducted in the eastern quadrant of Rome, in the area of Acacia Park 2, along Via di Pietralata. The investigations are overseen by the Special Superintendence of Rome of the Ministry of Culture, directed by Daniela Porro, and are part of a larger urban planning program that covers an area of about four hectares. Launched in the summer of 2022, the excavations are still ongoing and are returning an exceptionally interesting archaeological context, extending over about one hectare, documenting a frequentation of the area lasting more than seven centuries.

The scientific direction of the research is entrusted to Fabrizio Santi, an archaeologist from the Special Superintendency of Rome. The data that have emerged so far outline a sequence of occupation ranging from the 5th-4th centuries B.C. to the 1st century A.D., with traces of a more sporadic presence between the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D. as well. At the center of the identified context is a long road axis from ancient times, which crossed the area in an area characterized by the passage of a waterway, which flowed into the nearby Aniene River. Once the excavation operations have been completed, it is planned to launch a study aimed at defining an enhancement plan for the area, with the goal of returning to the city a new piece of its most ancient history.

“It is precisely in contexts like this,” explains Daniela Porro, Special Superintendent of Rome. “seemingly distant from the best-known sites of the ancient metropolis, that elements emerge that are capable of enriching the narrative of archaeological Rome as a diffuse city and that have contributed in a decisive way to its development. The modern suburbs thus prove to be repositories of deep memories, yet to be explored. Moreover, these findings confirm the importance of preventive archaeology as an indispensable tool for urban development to be associated with protection and accompanied by greater knowledge and appreciation of our heritage.”

“The identified tombs constitute important evidence of the occupation of this part of the suburbs by a wealthy family group, while the two monumental basins open up exciting research scenarios,” says Fabrizio Santi. “They could be structures connected to ritual or, less likely, productive activities or related to water collection: a thorough scientific study will allow to contextualize these findings and understand their role within the ancient landscape, in order to return to the community the authentic meaning of these testimonies of the past.”

The road represents one of the structuring elements of the site. The road axis is divided into two distinct sections: one closer to the present Via di Pietralata, made of beaten earth, and another in the direction of Via Feronia, dug directly into the tufa bank. Although the travel of the area must have been already older, the first evidence of a regularization of the road axis, oriented from northwest to southeast, dates back to the mid-Republican age, around the 3rd century BC. At this stage a massive retaining wall was built of tufa blocks, later replaced in the following century by a structure of uncertain workmanship.

In the 1st century AD the road was still in use and underwent further interventions. It was provided with a new beaten track and bordered by masonry in opus reticulatum, a sign of a more monumental arrangement of the route. The portion of the route in the vicinity of Via Feronia shows a period of use between the 3rd century B.C. and the 1st century A.D. and preserves, in its earliest phase, evident carriageway furrows incised in the tufa cut. From the 2nd-3rd centuries AD, a number of modest pit burials, arranged along the road axis, seem to document the gradual abandonment of the road and the transformation of its role within the landscape.

The road led to a small cult building, a sacellum with a quadrangular plan, small in size but of great symbolic and archaeological interest. The structure measures about 4.5 by 5.5 meters and is built with masonry in uncertain tuff work, with traces of plaster still visible on the interior walls. In the center of the room, in axis with the entrance, a square base of white-plastered tuff was found, which can be interpreted as an altar or part of an altar. On the back wall, also in the center, a masonry forepart must have served as a base for a cult statue.

The excavation revealed a particularly significant finding: the sacellum was built on top of a now disused votive deposit. Numerous votive offerings were found within this deposit, including heads, feet, female figurines, and two terracotta cattle. These are materials that direct the interpretation of the site toward a cult related to Hercules, a deity widely worshipped along the nearby Via Tiburtina, from Rome to Tibur, where there were several temples dedicated to him. Some bronze coins found in the context allow dating the construction of the sacellum between the late 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C., placing it fully in the Republican age.

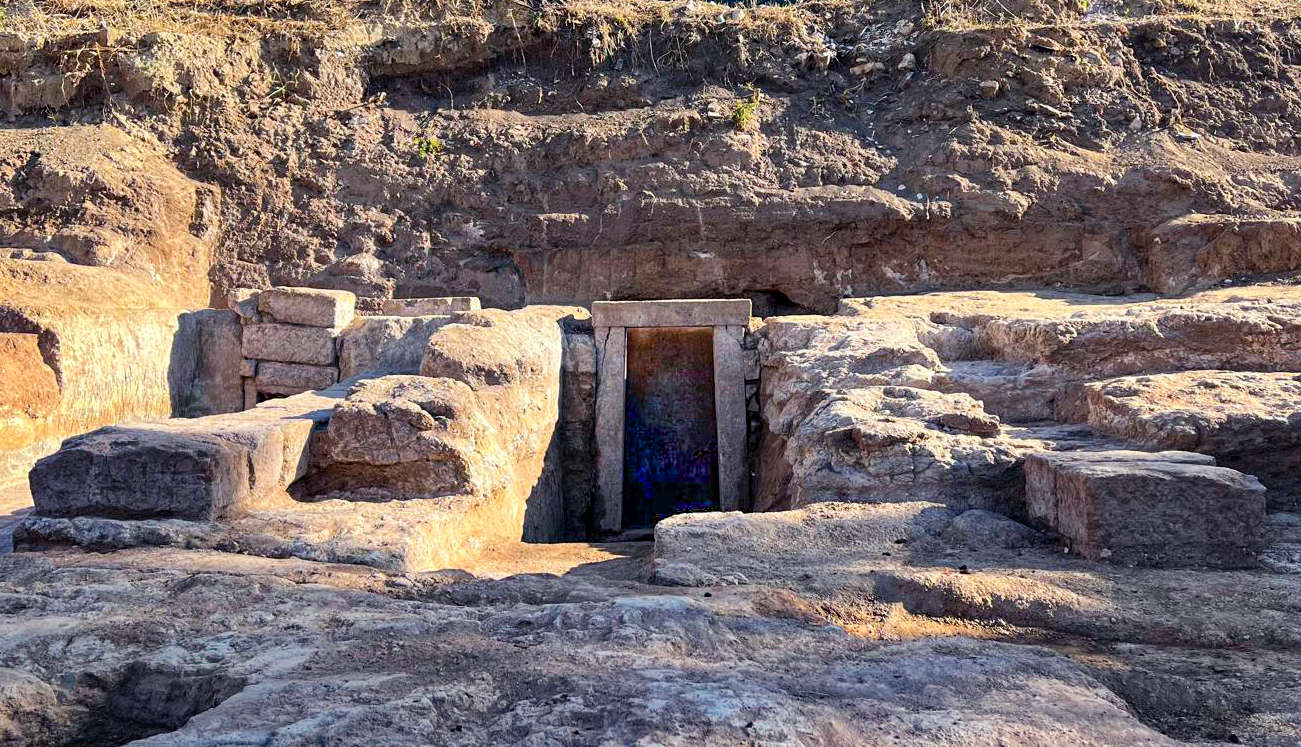

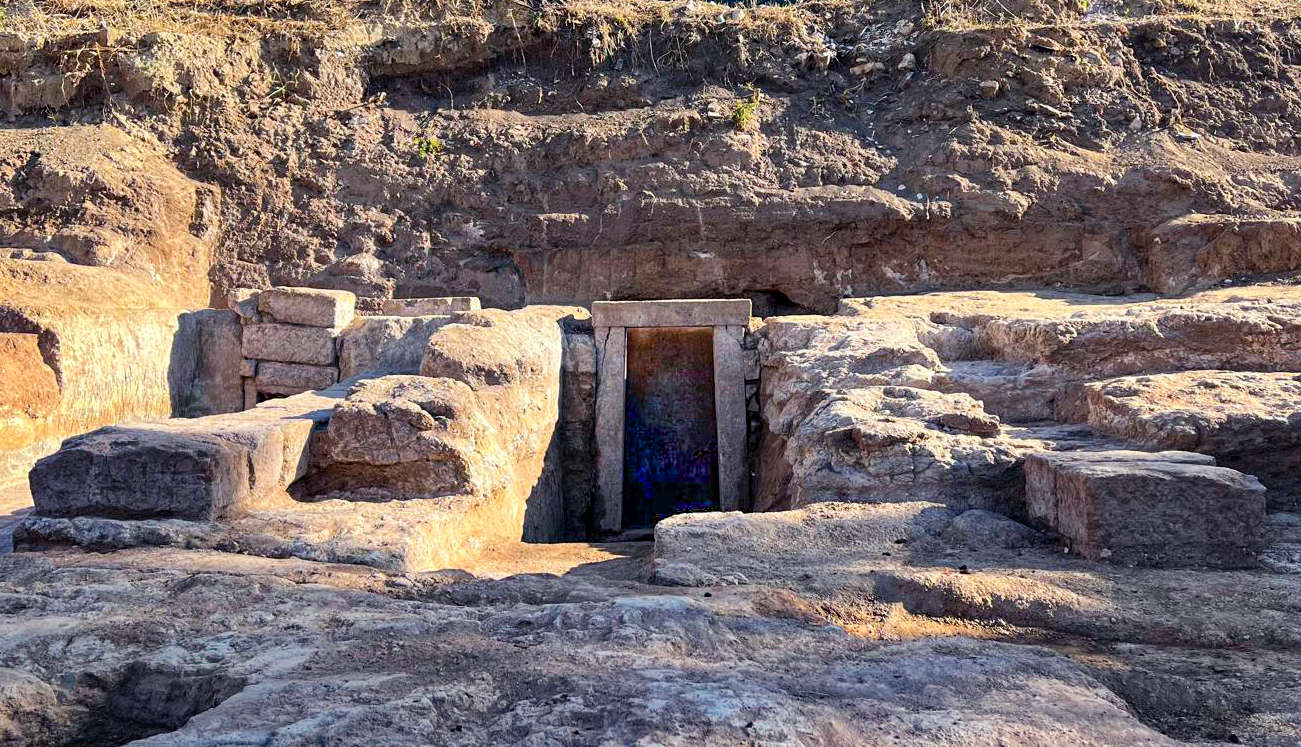

On the tuffaceous slope sloping down from Via di Pietralata, a funerary complex of considerable importance has also been identified. Two distinct and parallel corridors, the so-called dromoi, lead to two chamber tombs datable between the fourth and early third centuries B.C. The first, designated Tomb A, features a monumental entrance to the inner chamber carved into the rock. The portal, made of stone with jambs and lintel, was closed internally by a large monolithic slab. A large sarcophagus and three urns, all made of peperino stone, were found inside the burial. The grave goods included two intact vases, a black-painted bowl, a depurated ceramic jug, a mirror, and a small cup, also black-painted.

Tomb B, probably made at a slightly later time but still in the Republican period, in the 3rd century B.C., was enclosed by large tuff blocks. The chamber has on its sides benches intended for the deposition of the deceased. Among the human remains an adult male skeleton was identified, of which only part of the skull has so far been recovered. On this element the sign of a surgical drilling was recognized, a testimony of great interest for the history of ancient medicine. The two tombs were part of a single funerary complex that must have featured a monumental facade of tufa blocks, which has now largely disappeared. In fact, some elements appear to have been removed and reused as early as Roman times. The monumentality of the whole suggests belonging to a wealthy and influential gens, active in this area of the territory.

Among the most impressive structures that emerged from the excavation is the so-called east basin. It is a monumental structure about 28 meters long by 10 meters wide, with a depth of 2.10 meters. The basin was built in the 2nd century B.C., as indicated by the masonry techniques in opus incertum. From the 1st century AD onward, the structure seems to gradually lose its function, entering a phase of abandonment that culminates in its final closure at the end of the 2nd century AD. The concrete masonry was originally covered with a compact white plaster, now almost completely detached, of which only a few traces remain. The entire basin was crowned by a cornice of large tufa blocks. In the center of the two long sides are barrel-vaulted niches, while on one of the short sides a dolio was identified embedded in the concrete casting. On the other short side a small ramp lined with worked tufa blocks is preserved, but it does not reach the bottom of the pool.

Beyond the presence of water and collection systems, the function of the structure remains uncertain. The materials found, including architectural pottery and ceramic fragments with graffiti, suggest a possible cultic use, although a use related to production activities cannot be ruled out. The basin was fed by a system of channels that conveyed water both from the natural watercourse and from the slope still visible on the side of Via di Pietralata.

A second monumental basin, termed the south basin, has been identified not far away. This structure is dug into the tuffaceous bank and measures about 21 by 9.2 meters, reaching a depth of about 4 meters. The walls of the basin are lined with masonry made of irregularly arranged squared blocks, which can be dated to the 2nd century BC. A century later, additional masonry walls of reticulated opus quadratum and tufa were added, delimiting the top of the basin. Access was via a ramp made of large tufa paving stones, resting directly on the ground, followed by a second, narrower ramp made of concrete and paved with rectangular slabs, which allowed access to the bottom.

Even for the southern basin, the function is not yet clearly defined, mainly because no water adduction or outflow channels have been identified so far. However, the structure bears some significant similarities to the basin recently discovered at Gabii by the University of Missouri in collaboration with the Archaeological Museums and Parks of Praeneste and Gabii. In particular, the type of basalt paving of the access ramp draws comparison with the Gabii context, dated to the 3rd century B.C., for which a hypothesis of a sacred function has been advanced. The ceramic material found in the fill layers of the Pietralata basin suggests an abandonment during the 2nd century AD.

|

| Major archaeological discoveries in Rome: a sacellum, republican tombs and monumental basins |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.