Post-punk culture but also pop culture, a constructive and active rebellion against the contemporary art system, a small workshop in the center of Carrara where works made with a wide variety of expressive techniques (sculpture, painting, silkscreen printing, installations) are born: these are the elements that make Fronte Acciaio Cromato (F.A.C.), an artistic group born in 2015 in the city of marble, founded by Germans Stefanie Krome and Dominik Stahlberg, recently joined by Chinese Erika Gao. “Acciaio Cromato” is the almost literal translation of Stahlberg and Krome’s last names into Italian. “Front” is because their art is a kind of perpetual struggle: against a system made up of galleries, dealers, public relations that usually tends to cut off independent artists, and then again against speculation, against the arrogance of certain intellectuals, against the claim that art always has to say something, against conformism. All of this is done by exploiting the mechanisms of provocation (right from the name: F.A.C. refers, by assonance, to a well-known interjection of disappointment in English), but without letting it remain an end in itself.

Their works generally come to the audience in two times. The first half is precisely that of provocation: the images that the Chromed Steel Front proposes to the viewer are almost always uncomfortable, disturbing, could also be perceived as aggressive, but sometimes also as funny. The second half, on the other hand, is one of reflection, partly because F.A.C.’s works are anything but immediate. Their meaning often does not end at the image alone: one must read them deeply to establish a connection with them. “The majority of the public,” they declare on their website in a kind of manifesto explaining the basis of their actions, “is no longer attracted by too silly slogans or coercive stylistic measures.” And that is why Maurizio Cattelan ’s name echoes among their references: art, according to them, must be like a hammer. It must break, it must make people discuss. If necessary it must also hurt. But it can also make people smile: there are no prescriptions. The important thing is the dialogue with the audience: Stefanie Krome tells us that often even the most reluctant people change their attitude in front of a work of art, and welcome it, if a discussion is initiated. Relational art that feeds on post-punk aesthetics to desecrate, satirize, open horizons.

|

| Dominik Stahlberg, Stefanie Krome and Erika Gao |

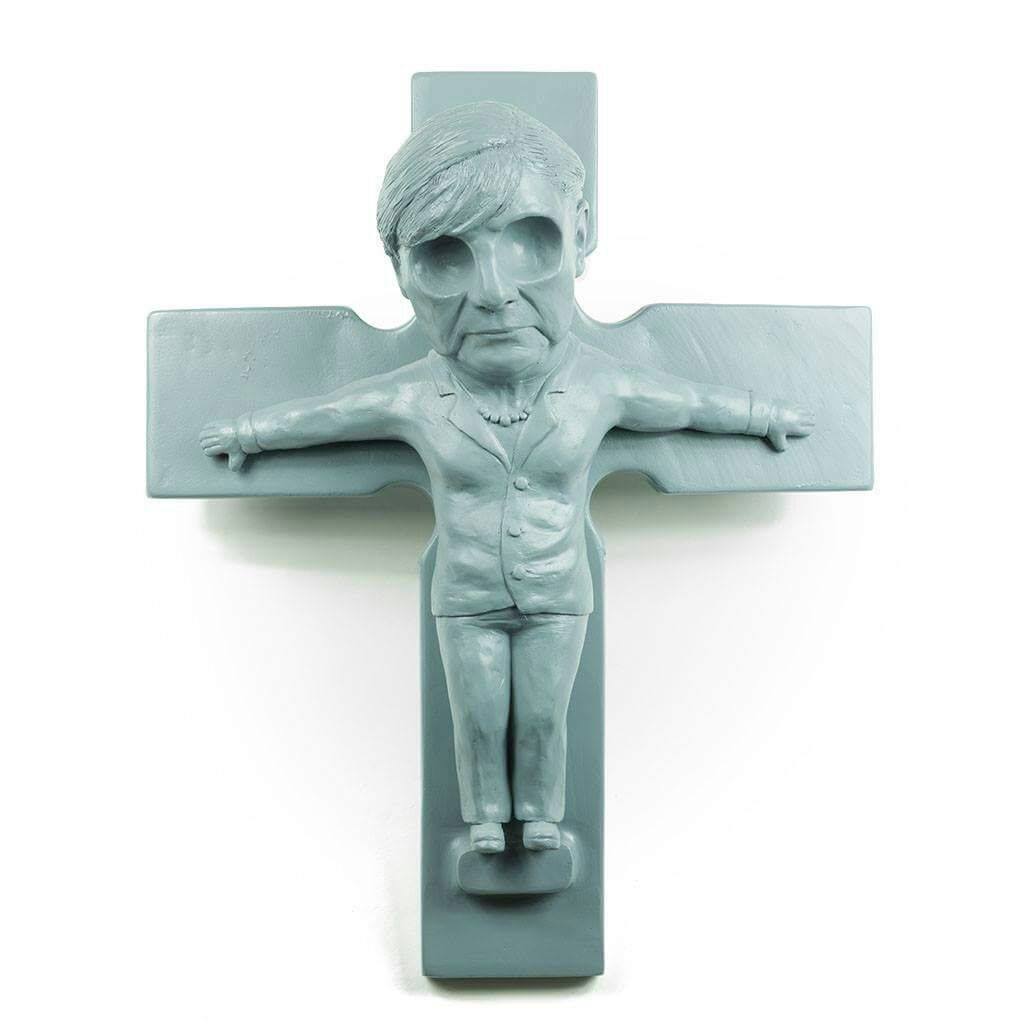

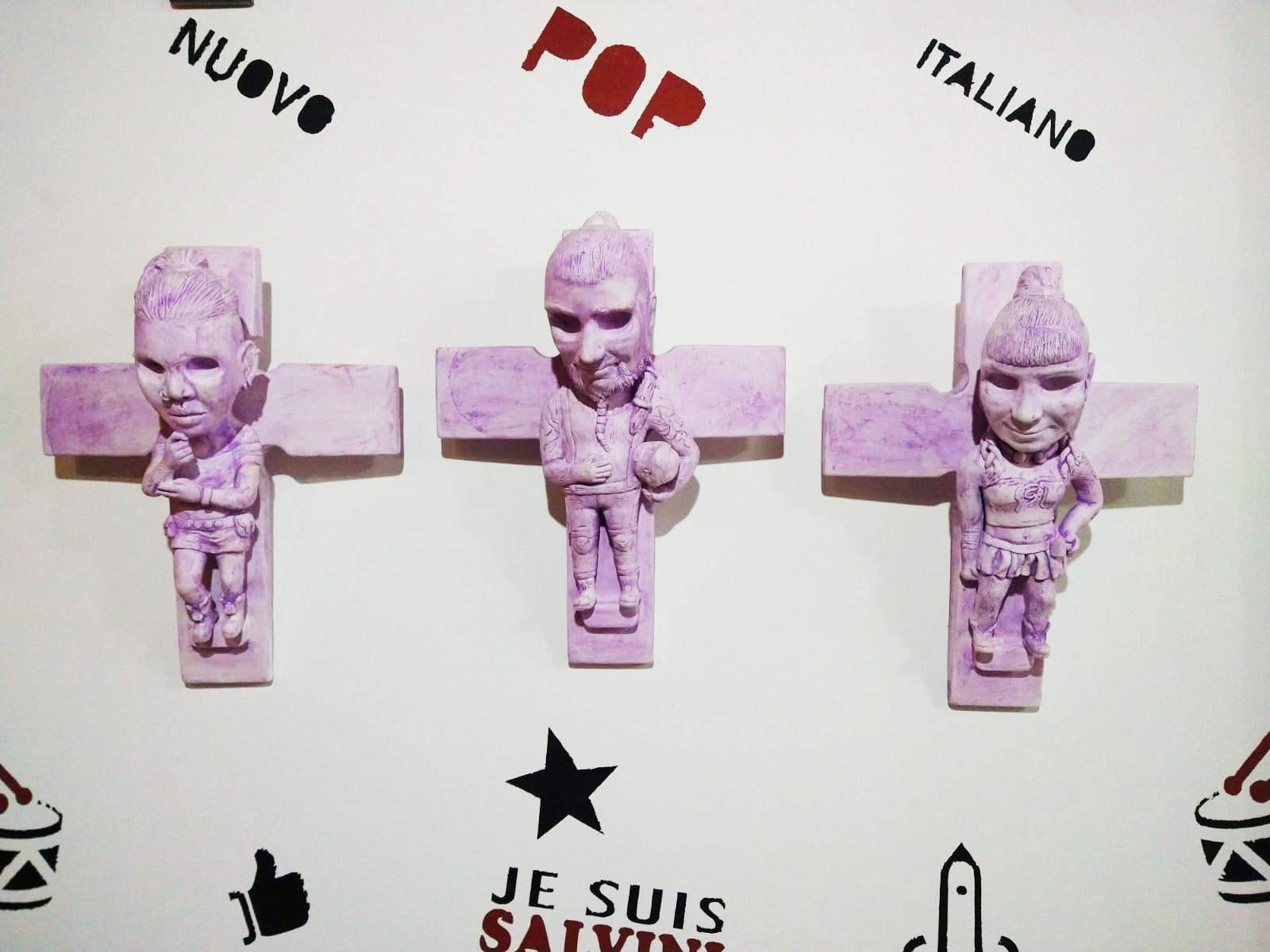

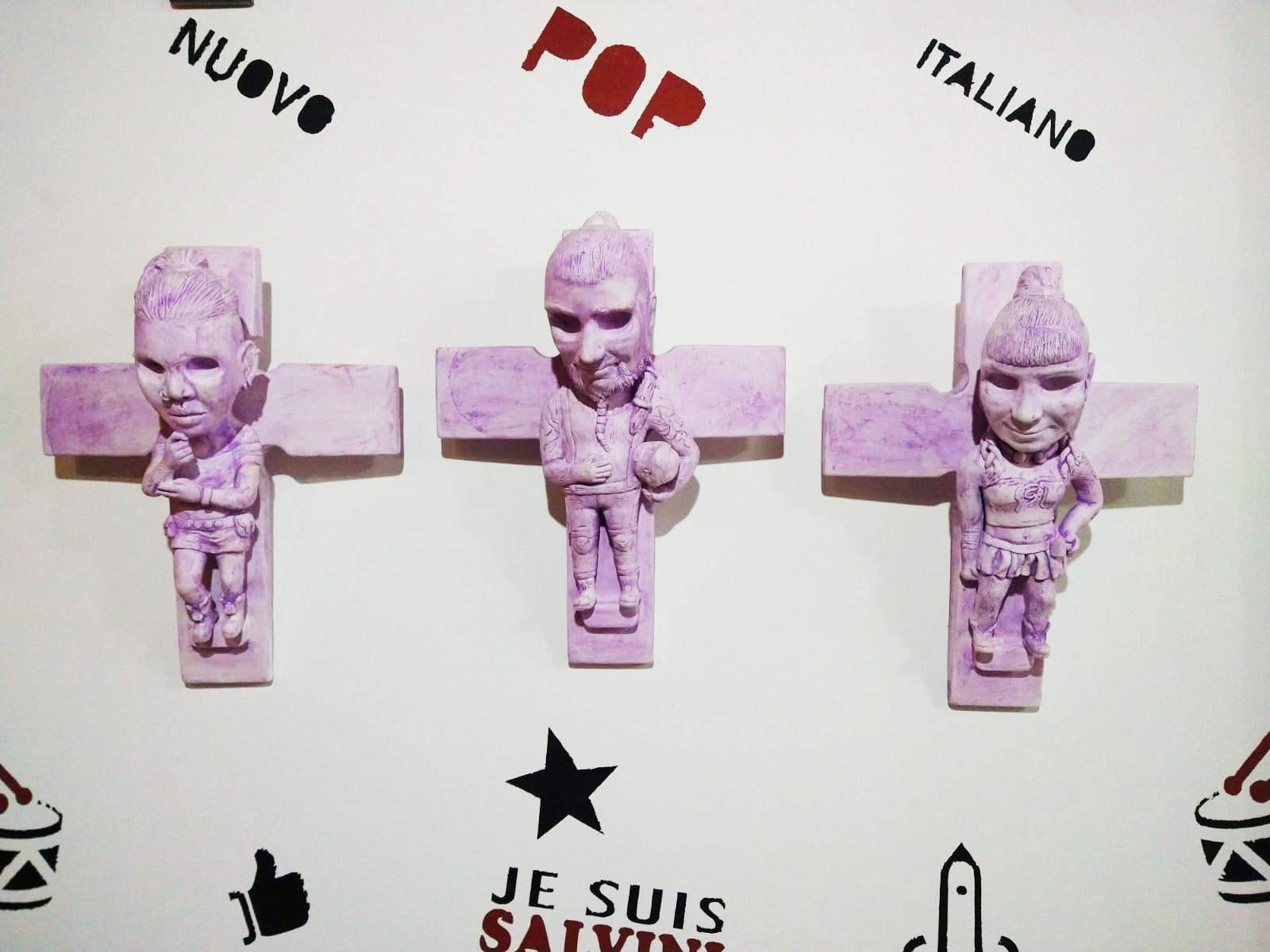

These are the intentions behind their best-known project, Cruxials: bizarre crucifixes made of organic resin depicting well-known and lesser-known figures. There’s Angela Merkel, Beppe Grillo, Michael Jackson, Lemmy Kilmister, Star Trek’s Dr. Spock, and then there are all the personalities of Carrara, from the director of the Academy of Fine Arts to the bartender in the historic center, not to mention the colorful characters who populate the city’s alleys night and day. Stefanie Krome explains that these works are not meant to be blasphemous, nor are they meant to be judgmental, although the first impact may make them seem so: the basic idea is that everyone has his or her own cross and carries it with them throughout life. The cross is thus elevated to a symbol of the evils that afflict our society, and thus becomes a means by which well-defined problems are identified and circumscribed. But there are also other keys to interpretation, one of which is very topical in the age of social media and easy judgments: in our world, the artists of F.A.C. explain, it takes very little to be crucified, to become thieves to be thrown to a bellowing crowd that shouts Crucifige at you (and Crucifige is moreover the title of the exhibition that in 2018 had presented Cruxials to the public). So, let everyone already have their personalized cross!

Several Cruxials are on display in the gallery-workshop of the F.A.C.: a splendid environment on Via Finelli, in the historic center of Carrara, a stone’s throw from the Cathedral. On one side is a forge where F.A.C. produces works in resin, plaster, marble, and stone making limited use of machinery and following traditional techniques (they also have a press with which they produce their silkscreens). And on the other, an exhibition space where their works are made known to the public, when they are obviously not out in the world at exhibitions and shows. The activity of Krome, Stahlberg and Gao, after all, is frenetic: in independent art circles, their names are well known. Stahlberg is a member of NO!art, an anti-art, avant-garde, internationalist movement that arose in New York in the late 1950s and was animated by the purpose of disrupting the more traditional art world, dominated by fashions, consumerism, and imperialism. Krome, on the other hand, is the coordinator for Italy of Sculpture Network, an international network of sculptors. Both of them grew up in the German Post-Punk culture of the 1990s, and studied sculpture. Krome has been in Italy since 2005 (so much so that she now calls herself “Italian by choice”): she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara and the University of Leipzig, and has participated in numerous sculpture symposia around the world, from Italy to Mexico, from Scotland to China, from Greece to Thailand. Studies at the Carrara Academy of Fine Arts also for Stahlberg and Gao: sculpture for the former, graphic design for the latter.

|

| Angela Merkel’s Cruxial |

|

| The Cruxial by Luciano Massari, director of the Carrara Academy of Fine Arts. |

|

| Erika Gao at work on a Cruxial |

|

| The three members of F.A.C. in Cruxial format. |

It is precisely sculpture, after all, that is the art form that gave rise to the group: both Krome and Stahlberg left Germany (they are both natives of Hildesheim, near Hanover) with the desire to study this art form in Carrara, having left with the myth of the city of marbles. And then, as Stefanie Krome further explains, they fell in love with the city and its atmosphere to the point that they decided to stop under the Apuan Alps. The Cruxials dedicated to the city’s characters, a sort of “Three-Dimensional Encyclopedia of Carrara,” as they call it, also manifests a desire to take root firmly in a community known to be historically very closed to newcomers (this has been the case for centuries: it is no coincidence that in Carrara, even with all the marble at its disposal, a true local art school was born only in the eighteenth century), and in a city that years ago, after carving out a prominent place for itself in the art world, had a much more pronounced international vocation, and that has been lost over time.

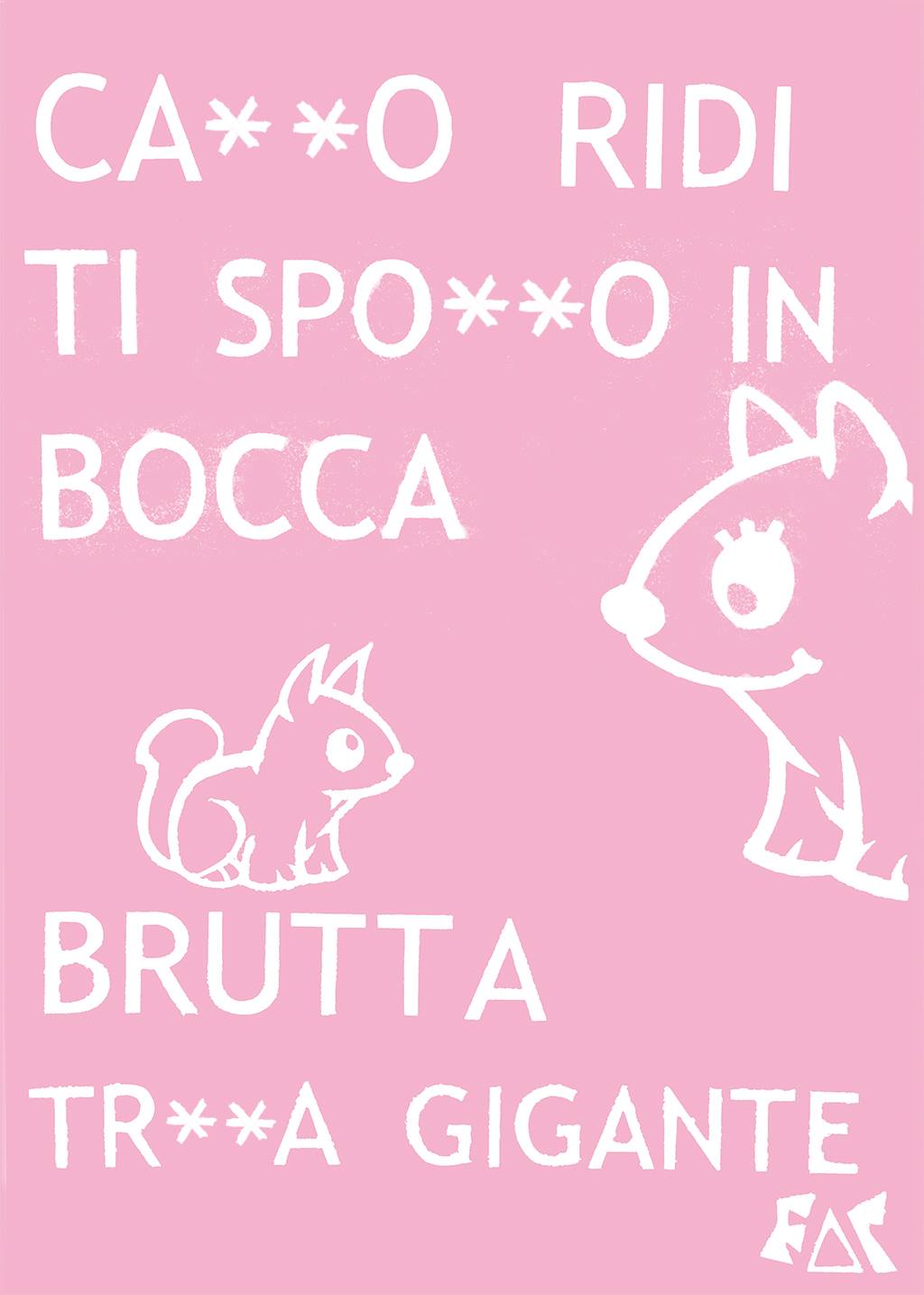

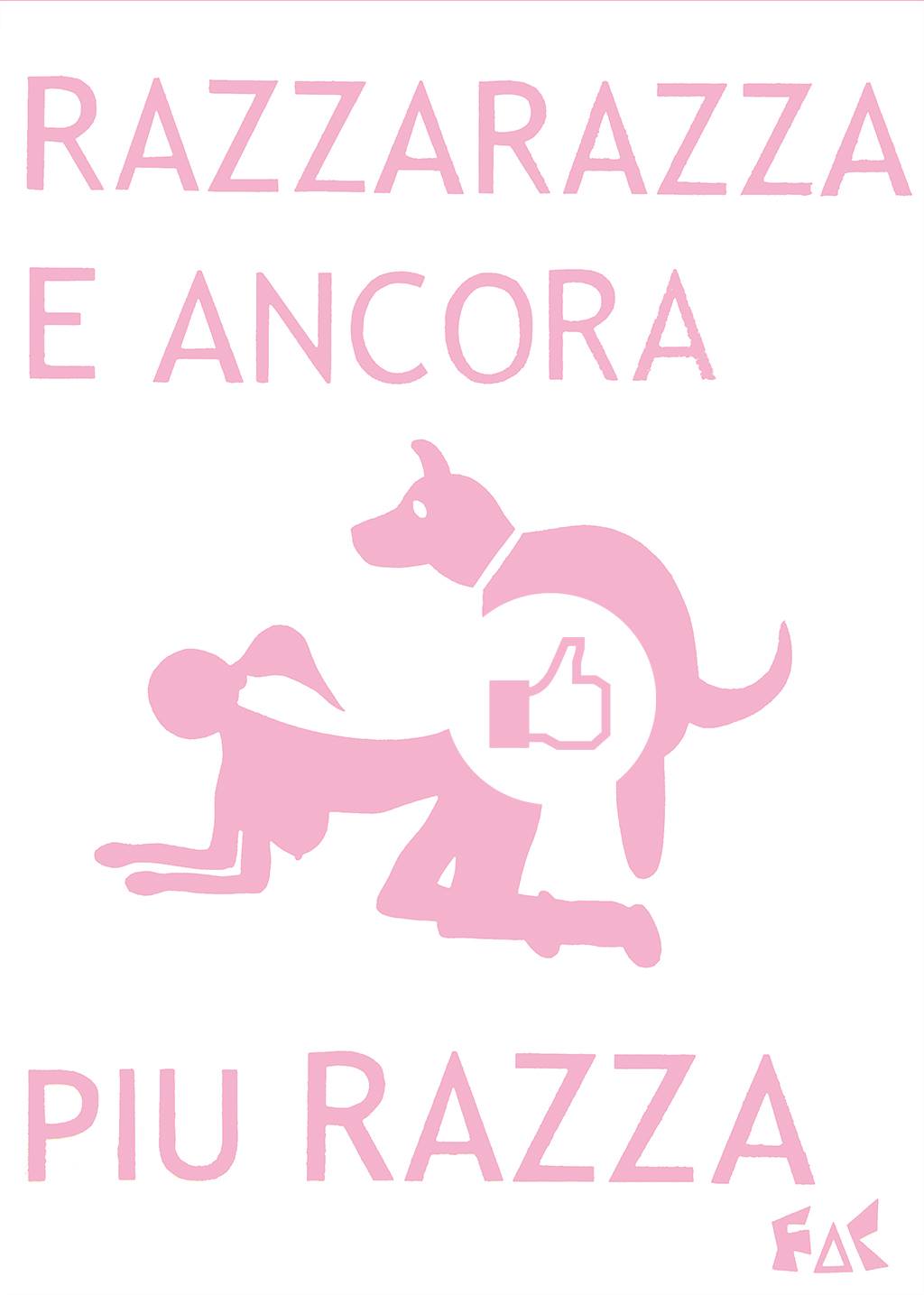

And settling in, however, has not been easy: it speaks of uprooting, adaptation, and diversity of cultures the Serigrafixe series, where Krome and Stahlberg included some equivocal phrases (and often even insults) that they heard spoken during their first years in Italy and whose meaning they could not understand. To let the audience “get angry or laugh with us,” say the F.A.C. artists. And so here are phrases like “You fucking laugh, I’ll cum in your mouth, you giant cunt,” or even “fuck me doggy style,” “It’s always good to be overrated,” and then a provocative amplexus with a dog and a woman (“Race, race and even more race” to protest the idea that certain races can rise above others, because in the end it is life in all its forms and with all its “genetic crossovers” that wins, with all its difficulties and complications, of course, but the loser is always those who thought to put limits and stakes).

|

| Opera from the Serigrafixeseries |

|

| Work from the Serigrafixeseries |

It will be easily noticed how in almost all the works of the F.A.C. the different tones of pink prevail: the reappropriation of this color, belittled by advertising and relegated to the role of color for boring little princesses or the prevailing tone of clothing for “pussies and transvestites,” is also one of the theoretical foundations of the Chrome Steel Front. Pink, Krome and Stahlberg assert, is the first color we see when we are born. It is a way of feeling that has nothing to do with the divisions between genders (it is perceived as such simply as a reflection of a canon imposed on us from childhood), and it is also, if you will, a way to unhinge machismo. Pink becomes almost a way of life, the most nonconformist of colors.

In the future of the Chromed Steel Front is what the Front has always tried to do: create opportunities for meeting, confrontation and dialogue through art. Over time, their space has become a popular place to visit, not least because visiting it means retracing the history of their young production, as works from the group’s beginnings, exhibition posters, as well as works in progress are displayed here. And meanwhile, the Front continues to work on new works and projects. Art, said their countryman Blixa Bargeld, is not something you do when you can do it, but when you have the urge to do it. And the Front always vividly feels the ardor of this need.

|

| Everyone has their own cross. The provocative art of the Chrome Steel Front. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.