Three works of exceptional quality, three variants on the same theme (that of the Holy Family), three paintings that speak of an artist, Bartolomeo Cavarozzi (Viterbo, 1587 - Rome, 1625), eager to escape for some time from the fierce competition that inflamed the art market in early 17th-century Rome and, therefore, intent on embarking on a long journey that would take him to Spain and make a stop in Genoa, in order to find new opportunities to express his art to the fullest: an experience destined to change the face of his painting forever. These are the elements that make up the exhibition Bartolomeo Cavarozzi in Genoa, curated by Gianluca Zanelli and set up at the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola, on the wall that usually houses the magnificent portrait of Giovanni Carlo Doria on horseback, executed by Pieter Paul Rubens, and momentarily absent due to a transfer to the Gallerie dItalia in Piazza Scala for the exhibition on the legacy of Caravaggio. And as is typical of the small exhibitions set up by the Ligurian museum, always animated by very solid research projects and laudable dissemination intentions, even the one that has Cavarozzi’s three canvases as its protagonists is appreciated for its precious quality, refinement and the depth of the scientific project.

At the basis of the exhibition, as anticipated, is the journey that Bartolomeo Cavarozzi made to Spain, where he stayed between 1617 and 1621, stopping in Genoa both on the outward journey and on the return: the stages and motivations of the journey have been reconstructed in great detail by scholar Marieke von Bernstorff, who gives a timely account of it in her catalog essay. The painter from Viterbo was part of a delegation that was accompanying Cardinal Antonio de Zapata to the Iberian peninsula, who had been entrusted with the task of reaching his native country from Rome to bring there the remains of Francisco de Borja y Aragon, the Jesuit general who had died in 1572 and who a few years later would go through the process of beatification first and then canonization (he would become a saint in 1671). But that is not all. Receiving Zapata and his entourage would be the Duke of Lerma, Francisco Gómez de Sandoval Rojas y Borja, a favorite of King Philip III: the sovereign harbored a desire to complete the Pantheon of Spanish kings in the Monastery of the Escorial, and for that reason Zapata brought with him Giovanni Battista Crescenzi (Rome, 1577 - Madrid, 1635), a nobleman, collector and amateur painter who had a reputation as a great connoisseur of art, since at the time the artistic judgments that were considered most authoritative were those made by those who possessed practical knowledge of the subject and had tried their hand (or continued to try their hand) with brushes and paints. Zapata probably thought that Crescenzi had been able to advise the king during the stages of organizing the work, as well as during the progress of the work. Crescenzi, as an art agent, another trade that he successfully carried out, thought of taking some of his protégés with him to introduce them to the demanding Spanish patrons, and Bartolomeo Cavarozzi was among the painters who were on close terms with him. It was, therefore, a decisive stay for the artist, then in his thirties, who was able to extend his clientele and update his language thanks to the contact with a new artistic reality and the possibility of consolidating relations with the other artists that Crescenzi had brought with him, first and foremost the Flemish Gerard Segers (Antwerp, 1591 - 1651), who shared with Cavarozzi a “pictorial style.” writes von Bernstorff, “which can be defined for both of them as an elegant adaptation of Caravaggio’s formal language,” and which “was oriented to the needs of the art market,” since “Segers’ and Cavarozzi’s works in some respects corresponded to the expectations and taste of Spanish patrons, who, rather than artistic invention, particularly appreciated forms of representation aimed at favoring decoration.”

Also of fundamental importance was the Genoese sojourn, the real subject of the exhibition: it is verisimilar that Cardinal Zapata and his retinue had stopped in Liguria for a couple of months, although we do not know the real reasons for the stopover (which was probably necessitated by security concerns). In fact, an unpublished note attests that the cardinal stopped in Genoa for “a month or two” and that he stayed in Pegli, in all likelihood at the villa of Carlo Doria, Duke of Tursi, one of the leading politicians of the Republic of Genoa: it therefore seems more than fair to assume that Cavarozzi had used the time spent in Genoa to study the works present in the city, to make frequent visits to churches, studios and collections, and to entertain relations with potential patrons. Observing the quotations and references that can be found in his paintings, we can assert with certainty that the artist used to frequent the collection of Giovanni Carlo Doria, the great collector who belonged to a different branch of the family than the one from which the Carlo who had hosted Cardinal Zapata and provided him with galleys to travel to Spain came: and this also because, specifies in his essay Daniele Sanguineti, who is credited with reconstructing the relationships Cavarozzi forged in the city, “Giovanni Carlo’s taste could not have been more in line with the proposal of attractive modernity practiced by Cavarozzi and based on the restitution of reality by means of the image painted in a blandly but decidedly Caravaggesque key.”

|

| The Bartolomeo Cavarozzi exhibition in Genoa |

|

| The Bartolomeo Cavarozzi exhibition in Genoa |

Cavarozzi, in fact, had been able to refine and smooth out the most extreme points of the innovations introduced by Caravaggio in order to propose to his patrons a style that, while not renouncing that truthful representation of the natural that had changed the course of art history, was at the same time capable of satisfying the needs of a clientele with an elegant taste and who appreciated harmonious, balanced compositions, pervaded by a certain sweetness that, in the Genoese works of the Lazio painter, softens the characters but does not alter their real presence. The first work one encounters in the exhibition, a Sacra famiglia preserved in Turin in a private collection but once belonging to the Spinola family, immediately appears to the visitor as a summary of the experiences and suggestions Cavarozzi had accumulated up to that point: a purely Caravaggesque substratum updated on the best the artist could find in Genoa. In the composition, Saint Joseph appears set back in an unusual manner compared to traditional iconographic customs, with the result that the dazzling light that falls from above affects only the Madonna and her child, giving their figures an almost monumental emphasis. We cannot establish with certainty whether this is a painting executed directly in Genoa, or whether it is a work on which the artist worked during his Spanish sojourn: however, it is undeniable that the work presents many points of contact with what Cavarozzi had been able to see in the Ligurian capital. Sanguineti noted how the child’s attitude appears almost identical to that of the putto that appears in the lower left corner of Rubens’ Circumcision preserved in the Church of the Gesù in Genoa, which was commissioned from the great Flemish painter in 1604 by Marcello Pallavicino, a Jesuit, who intended it to be destined precisely for the house of worship located near the Ducal Palace.

Another “Genoese” motif that returns in Cavarozzi’s painting is the pose of Saint Joseph, who rests his chin on his right hand and shows an expression characterized by a dreamy gaze, which avoids meeting the eye of the observer: this is an attitude similar to that of one of the characters who appear in theEcce Homo of the sanctuary of the Infant Jesus of Prague in Arenzano, near Genoa, a painting that Gianni Papi already in 1990 had referred to Caravaggio himself (although critics, on this last point, disagree). And again, the layout of the main figure recalls that of the Holy Family with St. John the Evangelist and an Angel, a work by Giulio Cesare Procaccini once in the collection of Giovanni Carlo Doria and now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. Of the provenance of Cavarozzi’s painting we know nothing, but it is certain that the painter made it for a Genoese patron, since there is a substantial theory of other works of art in Liguria that, in whole or in part, reproduce it: it is enough to consider the San Secondo invoking the protection of the holy family over the city of Ventimiglia, a work by Giovanni Carlone in which the holy family is completely identical to the one that appears in Cavarozzi’s work, or copies such as the one by Giovanni Andrea De Ferrari, or even Domenico Fiasella’s Sacred Family from the Rizzi Gallery in Sestri Levante (and Fiasella was, moreover, a painter with whom exchanges with Cavarozzi seem to have been fruitful and reciprocal), in order to have robust elements of evaluation that allow the commissioning of the painting now housed in Turin to be referred to the Genoese sphere.

|

| Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, Holy Family (1617; oil on canvas, 156 x 118 cm; Turin, Private Collection) |

|

| Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, Holy Family, detail |

In the center of the wall, the visitor encounters the Sacred Family with St. John today owned by the Robilant+Voena gallery, but once in the collections of the Spinola d’Arquata family: discovered and published in 1916 by Roberto Longhi (who nevertheless proposed an attribution to Orazio Gentileschi, only to correct himself in 1943 and refer the canvas to the master from Viterbo), the work has a particularly complex history, retraced and reconstructed with great detail by Matteo Moretti in the catalog entry he compiled. Interestingly, the painting is mentioned in two files of the Documentation Center for History, Art and Image of Genoa, from which we learn that the work was exhibited for some time at the Palazzo Bianco museum, with erroneous attribution to Guido Reni: the datum is significant because it testifies to a further evolution of Bartolomeo Cavarozzi’s style, who with this painting, the later of the three exhibited in the small Palazzo Spinola review, would seem to attest to his own knowledge of Guido Reni’sAssumption executed for the Durazzo altar in the Gesù church and sent to Genoa in the summer of 1617, at a time after the departure of Cardinal Zapata and his retinue for Spain: it is therefore safe to assume that Cavarozzi had the opportunity to study the Bolognese’s work during his probable second stay in Genoa.

In fact, the Holy Family of the Viterbo artist appears cloaked with evident suggestions of Reni, particularly evident in the face of the Virgin: a type that differs from those that had appeared up to that time in similar paintings and that, on the other hand, shows a clear rapprochement to the ethereal Madonnas of Guido Reni, such as the one that appears in theAssumption of the Gesù church. Sanguineti then pointed out the close dependence of the Saint Joseph on anAssumption apostle, whose features (the long white beard, the gray hair, the long straight nose, the deep eye sockets, the rather pronounced cheekbones) are taken up as much as the posture, in profile, and even the expression. Then there are further new elements, starting with the remarkable landscape piece that represents a departure from the typically Caravaggesque somber backgrounds and within which, Matteo Moretti specifies, “an imposing crenellated structure can be seen , which seems to recall the ancient architecture of the manors and fortresses that still dot the hills of the Viterbo area, such as the castle of Torre Alfina, near the Sasseto woods, whose towers, with their more hanging arches rather protruding below the battlements, recall the concise Cavarozzian depiction in the background.” a passage so precise as to suggest that the artist wanted to include, in the work, an immediate echo of his own land. And again, a new element is the child who frets in his mother’s arms and tries to reach Saint John, as opposed to the more placid children who instead populated the homologous scenes performed earlier. Such as the one seen in the last painting in the exhibition, the Holy Family from the Pinacoteca dell’Accademia Albertina in Turin, a work probably referable to the artist’s Spanish period: of the three paintings, it is the one in which the rendering of the textiles evokes the greatest feelings of tactility. The preciousness of the fabrics and their precise, almost hyperrealistic description was a motif particularly appreciated by Spanish patrons, and Cavarozzi, in this work, demonstrates a mastery of it evidently acquired to better satisfy his new clientele.

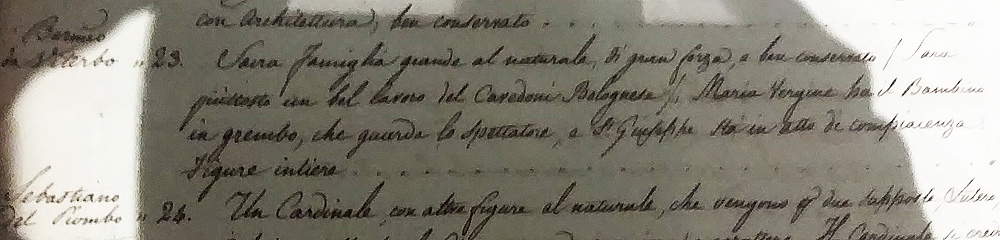

The painting is first mentioned in an inventory drawn up in 1706 as an attachment to a deed that conveyed to Costantino Balbi, a leading member of one of the most prominent families of the Genoese nobility, a substantial number of paintings by his late father Bartolomeo: these included Cavarozzi’s Holy Family, which was held in high esteem, comparing it to works by Rubens, van Dyck and Titian in the same collection. The work left the family’s collections in 1823, with destination Turin, and came to the Accademia Albertina a few years later thanks to a donation made by Vincenzo Maria Mossi di Morano, who probably bought the work from the last heirs of Costantino Balbi. The Madonna’s face, imbued with sweetness and lightly veiled with melancholy, her dignified pose, the tenderness of the child clinging to his mother’s robe, the good-naturedness of St. Joseph leaning on his staff, combined with the technical details (the aforementioned tactile rendering of the fabrics, the refinement of the highlights that highlight the draperies and bring this realization close to the works of Orazio Gentileschi, the admirable care of the forms, almost “maniacal,” as Sanguineti points out) denounce that attempt to mitigate the most extreme peaks of Caravaggio’s art that Bartolomeo Cavarozzi pursued at this stage of his career. Next to the painting on display is a document from 1823, a list of paintings that Costantino Balbi iunior received as an inheritance from his grandfather, namely the aforementioned Costantino Balbi, preserved in the Spinola Archives and in which the painting by “Bartolomeo da Viterbo” is recorded as “Sacra Famiglia grande al naturale, di gran forza, e ben conservato / Sarà piuttosto un bel lavoro del Cavedoni Bolognese /; Maria Vergine ha il Bambino in grembo, che guarda lo spettatore, e S. Joseph stands in an act of complacency. Intiere figures.”

|

| Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, Holy Family with St. John (c. 1620; oil on canvas, 195 x 140 cm; London, Robilant+Voena) |

|

| Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, Holy Family (c. 1617-1620; oil on canvas, 176.5 x 132.9 cm; Turin, Pinacoteca dell’Accademia Albertina) |

|

| Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, Holy Family, detail |

|

| The mention of Bartolomeo Cavarozzi’s work in the list kept at the Spinola Archives |

It is possible to read the Palazzo Spinola review, which looks at a decidedly narrow period (the years examined are those between 1617 and 1620), as a moment of insight into a not minor episode in the history of Genoese art, since Bartolomeo Cavarozzi’s stay in the city, however brief it had been, nevertheless had an echo destined to resonate for some time in the city: many were the Genoese who boasted in their collections a painting by Cavarozzi, whom it is possible to identify as one of the first artists (he can be placed side by side with Orazio Gentileschi and Simon Vouet) to have spread Caravaggesque instances in Liguria. The 1710s and 1920s represented a crucial moment in art history for Genoa: it was during this time that the local school saw the presence of numerous artists from outside the city (in addition to the aforementioned Gentileschi and Vouet, the names of Rubens and van Dyck are worth mentioning, but the presence in the city of Flemish artists was dense, and these relationships are well investigated in the exhibition on Van Dyck and his friends currently underway at Palazzo della Meridiana), as well as the return of many Ligurian artists who had spent decisive periods of study abroad, such as Domenico Fiasella, who returned to Sarzana in 1616 after spending several years in Rome. These were all experiences that enabled Genoa to become an artistic hub of international caliber: Cavarozzi’s presence constitutes an important piece of this mosaic, and the exhibition succeeds in framing this piece with great precision and punctuality, presenting the public with three extraordinary works that offer one of the most elegant declinations of Caravaggism, rendered by the painter whom biographer Giulio Mancini described as “of very pleasant habits [...] all reserved and modest [...] universal of all things et con tutti i modi d’operare.” The timely information panels in the room also make us aware of the fact that Cavarozzi’s works once present in Genoese collections have been dispersed, and the exhibition is therefore an opportunity for three of these works to be reunited, thus having a chance to return to Genoa after centuries.

Of particular importance is the highly enjoyable and thorough catalog: in addition to the essays by Marieke von Bernstorff and Daniele Sanguinetti, which, as mentioned, focus the one on Cavarozzi’s trip to Spain, the other on his Genoese sojourn (the conclusions are summarized in the final “notes for a biography” compiled by Gabriella Aramini), and the entries compiled by Gabriele Langosco, Daniele Sanguineti and Matteo Moretti, the catalog consists of an essay by Giuseppe Porzio that tries to give an (affirmative) answer to the question of the “Bartolomeo Cavarozzi painter of still lifes,” and a contribution by Gianluca Zanelli around the disregard of Costantino Balbi iunior’s collection. The catalog thus presents the novelties that have emerged from the studies, thanks to which it has been possible to retrace with some precision the years in which Genoese art began to be marked by Cavarozzi’s inspiration, in addition, of course, to the movements that the Viterbo painter made between 1617 and 1620, even if the lack of documents at the moment does not allow us to have a more precise picture than that proposed by the review and which we have tried to summarize here: a volume that is therefore configured as a valuable tool that completes a valid and quality review.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.