by Jacopo Suggi, published on 19/07/2021

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Mario Puccini. Unintentional Van Gogh," in Livorno, Museo della Città , from July 2 to September 19, 2021.

In the 20th century, in a sunny Italian province, a branch of artists was giving birth to one of the most interesting artistic experiences on the peninsula. In the city of Livorno, the twentieth century saw an inexplicable proliferation of outstanding artistic personalities, astounding when one considers the size of the city and its certainly not ancient artistic tradition.

“Leghorners are individuals outside the group even when they form a group,” says Vittorio Sgarbi: “different, solitary, irreducible,” in short, “anarchists.” There are many important names that make up this group, of which Amedeo Modigliani is surely the most famous, while Mario Puccini (Livorno, 1869 - Florence, 1920), who was, on the other hand, highly appreciated during his lifetime, remains quite unknown to the general public. If Livorno was ungrateful to Modigliani, so much so that the news of his death was given only through a skimpy newspaper blurb as he was the brother of the Honorable Giuseppe Emanuele Modigliani, upon Mario Puccini’s death many artists and intellectuals rallied around this figure, who was already looked upon with much respect in life, and experienced as the true heir of the great master Giovanni Fattori. Puccini was juxtaposed with the Macchiaioli master not only because he had long been watered down by his lesson, but also because of that isolated, shy character, far from worldliness and intellectualism, often masked behind a mask of an uncultured painter, which both artists cultivated.

One wanted to see both as proponents of a painting where the real was instinctively mediated through great artistic sensitivity, a rather limiting view of Puccini’s art. It was precisely to honor the remains of Mario Puccini that the Leghorn artists formally constituted themselves into the Gruppo Labronico, a group that celebrated a century of activity.

|

| The portrait section, second on the right Puccini’s Ave Maria juxtaposed with Silvestro Lega and Giovanni Fattori |

|

| Mario Puccini and Giovanni Fattori in comparison |

|

| The comparison between the master Fattori and Puccini on the figure of oxen |

|

| Glimpses of the port of Livorno so beloved by Puccini |

|

| The works of Alfredo Müller, Plinio Nomellini and Benvenuto Benvenuti |

|

| The Unintentional Van Gogh section |

Last year the centenary of Amedeo Modigliani’s death was celebrated in Livorno with a major exhibition, but because of the pandemic the exhibition dedicated to Mario Puccini, who also died like Modì in 1920, could not be held. But today, fortunately, we no longer have to deprive ourselves of the wonderful experience of encountering the art of Mario Puccini: the great monograph opened in Livorno last July 2 comes 6 years after the exhibition Mario Puccini: The Passion of Color held in Seravezza in 2014 and curated by the same curator of the Livorno exhibition, Nadia Marchioni. And fortunately we are not in front of one of those now overused exhibitions reproposed over time identical, renewed only partially in the title. No: the Livorno exhibition, Mario Puccini. Unintentional Van Gogh, as every exhibition should do, does not give up nurturing new research and studies, documentary insights, clarifications and art-historical reconsiderations, and the much richer catalog than the previous one is proof of that.

The works in the exhibition are for the most part unpublished, and this was made possible also by the important collection of Ugo Rangoni, made available by his heirs. It is a collection never before seen on display and whose works, some eighty in number, have long been locked away in private rooms. The Livorno exhibition aims to rekindle interest in this extraordinary figure, and we are confident that to some extent it will achieve the hoped-for success.

Entering the halls of the Museo della Città, a first section frames Puccini’s beginnings as a painter and particularly as a portrait painter-a production he would later deal with infrequently. Here we see Puccini’s pupillage at Fattoria Firenze, and Silvestro Lega’s reference for a naturalistic and intimist painting, evident in works such as Ave Maria. The two great artists are featured in the exhibition and shrewdly placed in comparison, as are some works by Plinio Nomellini, whose tangencies with Puccini are evident. The two were often close, and Puccini would later look again to his colleague, almost of the same age, drawing updates for his painting.

|

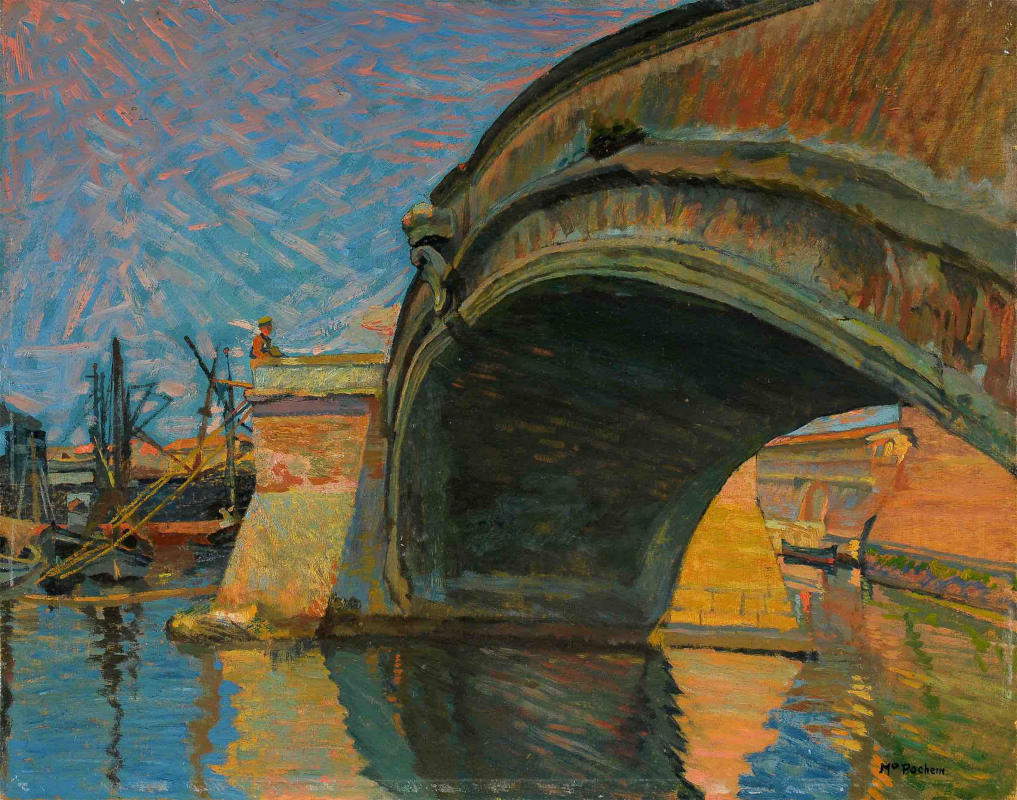

| Mario Puccini, The Bridge at the Sassaia (oil on panel; Rangoni collection) |

|

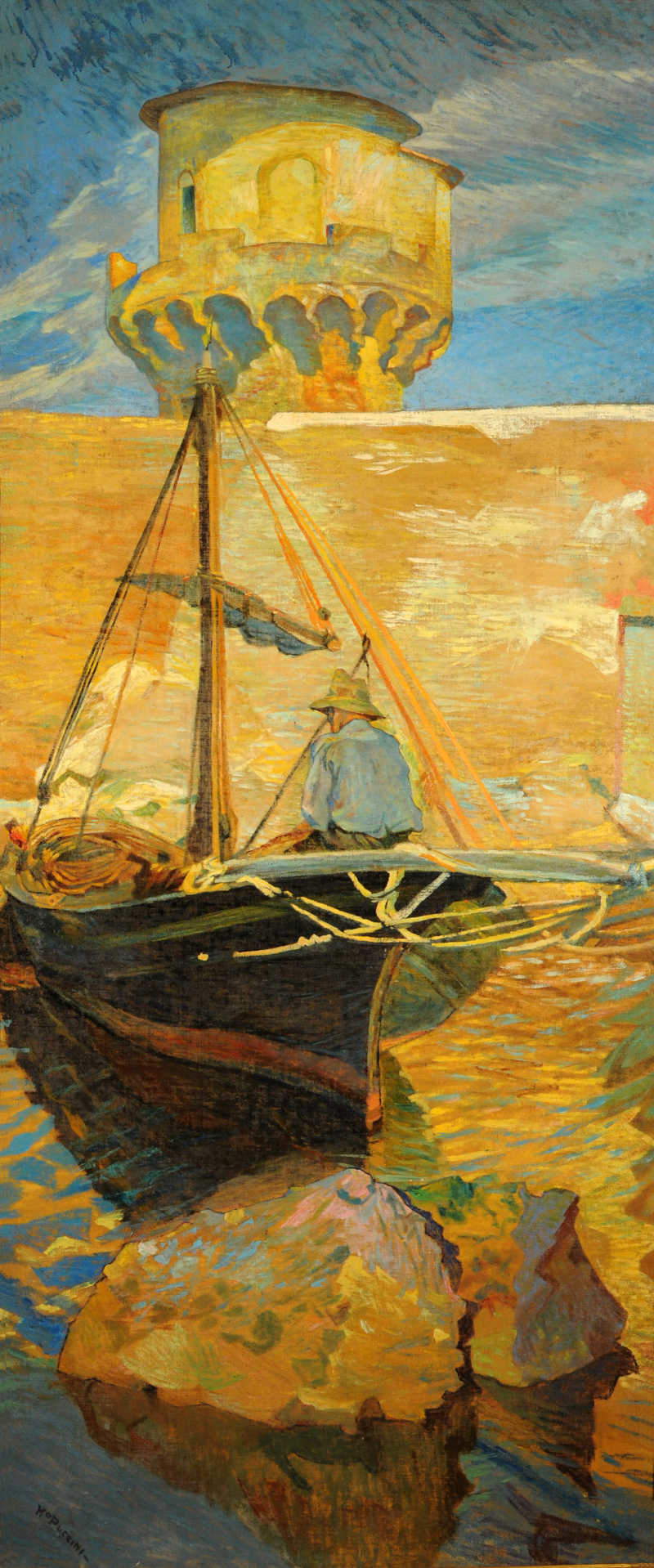

| Mario Puccini, The Lazaretto (1911; oil on canvas; Livorno, private collection) |

|

| Mario Puccini, Mutton Market at Digne (oil on cardboard; Rangoni collection) |

|

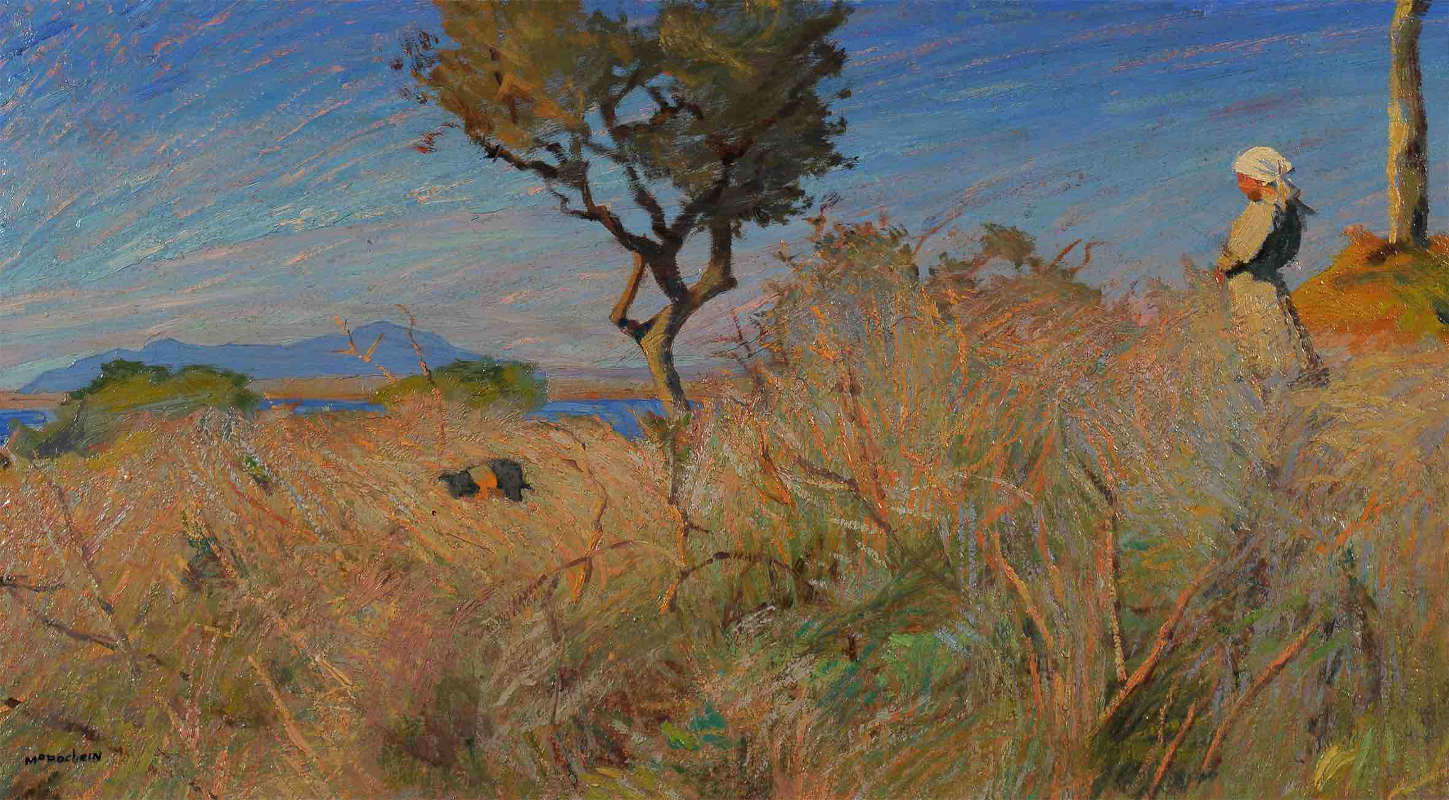

| Mario Puccini, Farmhouse near Orbetello (oil on board; Rangoni collection) |

|

| Mario Puccini, Swine keeper (oil on panel; Rangoni collection) |

|

| Mario Puccini, The Haymaker (oil on panel) |

|

| Mario Puccini, Oliveto con contadinella e bufali (oil on panel; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

The second section, of a biographical nature, introduces the artist presented through the few surviving documents and some self-portraits, which tell of the problems of mental instability that at least from 1893 affected Puccini, so much so that he was forced to take refuge in an asylum in Siena for a long time, perhaps also as a result of some problems with his father and family, which, however, seemed to support him for a long time. A biographical node of the artist, the events around the artist’s mental health over the years have given way to tasty but baseless anecdotes, such as the myth of the mad and primitive painter. For a long time these problems kept him away from art, and it was not until around 1901 that Puccini seemed to re-enter painting and artistic life in Leghorn. Llewelyn Lloyd, another prominent Labronian artist, tells us of a Puccini busy making ends meet through a variety of expedients, as a waiter, maker of embroidery designs, as a peddler for example.

The works on display show extraordinary essays of Puccini’s painting, still in the Factorian groove for that translation of the real into solid compositions where the study of light and tenacious respect for drawing never fail. But Puccini interprets the Factorian lesson with freer and more exaggerated brushstrokes and colors: in an exquisite little room Fattori’s immortal oxen are set against Puccini’s, the reference is blatant, almost a quotation, but in the National Gallery of Rome work Bovi all’Uliveta, the oxen become almost a chromatic abstraction and the compressed composition brings to mind certain hallucinatory landscapes of Chaïm Soutine.

Puccini’s reputation as an uncultured painter uninterested in novations in painting is a dogma that is largely demolished by the works in the exhibition and the essays in the catalog. Puccini must at first have looked carefully at some of his colleagues, not so much to infer easy solutions, but to free himself from the heavy yoke of Factorian truism. Artists such as Plinio Nomellini, Alfredo Müller, and Benvenuto Benvenuti offered examples that ranged from Impressionism to Divisionism. But also the solutions offered by Oscar Ghiglia, Giovanni Bartolena, and Ulvi Liegi must have had some appeal and suggested that Puccini pursue and refine his own poetics, also updating himself on solutions from France mediated by these artists.

Puccini fine-tunes a personal vision: his frayed and loose brushstrokes, unlike the impressionistic brushstrokes of his colleagues, do not deflagrate or implode but, through a dense and intricate weaving, tighten and frame his figures in a chromatic inlay. And here he performs in his most reckless perspectives and foreshortenings, when he reveals in a few centimeters of planking the deepest soul of the port city of Livorno. In an anti-heroic and anti-monumental vision, devoid of any narrative intent, sailing ships, steamers, navicelli and gozzi become a pretext for daring chromatic compositions, where the sails, bollards, ropes and tops are precious backgrounds and tesserae of shiny mosaics: a splendid example is Barca con pescatore from the Rangoni collection. Far from the clamor of picturesque visions, anonymous nooks and crannies, like the walls of an ancient lazaretto attract the artist’s attention. In the halo of the uncorrupted and naïve painter, Puccini’s hagiography has been written with an autarkic flair, particularly by Lloyd, who in the biography claims Puccini’s estrangement from any avant-garde solution, so much so that he was bored, in front of photos of the works of Cézanne and Van Gogh.

|

| Mario Puccini, Self-Portrait (1914; private collection) |

|

| Images of the everyday impressed by Puccini |

|

| Some of Puccini’s landscapes |

|

| The room dedicated to Caffè Bardi |

|

| Umberto Fioravanti, Female Bust (1909), Puccini in the background |

|

| The room of Puccini’s graphics |

"An unintentional Van Gogh" was called by Emilio Cecchi, but then he was not so unintentional. Thanks to the few voices outside the chorus, such as those of the very fine collector Gustavo Sforni, it was possible to begin to reconstruct, in Vincenzo Farinella’s masterful essay in the catalog, the figure of an up-to-date artist, a reader of the “Voce,” indebted to the work d Monticelli, perhaps known during his stay in Digne, a guest of his brother. Adolphe Monticelli was an elective master of Van Gogh, an artist whom, according to the catalog, Puccini certainly had the opportunity to admire in the First Italian Impressionist Exhibition held in Florence in 1910. The Dutchman’s Il Giardiniere, a work that later entered the Sforni collection and is now in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, and Paul Gauguin’s Végétation tropicale, now in Edinburgh, were on display.And in certain paintings, where Puccini completely frees himself from any desire to translate from life, such as the second panel of the lazzeretto(Eclipse of the Sun, the Fountain of the Old Pier, Livorno Pier, Sunset at Sea) the tangencies between the two become apparent. The chromatic lyricism becomes more violent, the textural impasto denser and the brushstrokes nervous, the pure color takes on a constructive value. In the exhibition we discover Puccini’s beloved universe, a world that speaks of the everyday, of humble figures bent by fatigue.

Dazzled by the Labronico’s colors, the eyes find rest in two excellent sections, the one dedicated to the Caffè Bardi, a meeting place for artists and intellectuals open in Livorno from 1908 to 1921, where Puccini painted a panel, displayed in the exhibition along with the works of other famous artists, catalyzed by an interest in Symbolist sirens from Northern Europe; and in the appendix dedicated to Puccini’s graphics. The charcoals reveal how Puccini never abdicated drawing, still a reminiscence of Fattori’s lesson.

More than 150 works, all of a high standard, a careful study that makes us applaud the great work of the curators, and the elegant and refined spaces of the setting make this exhibition probably one of the most interesting of the Tuscan and Italian summer. The only jarring note: we regret not seeing Puccini’s great masterpiece, La metallurgica, on display. But on the whole it is a unique opportunity to rediscover this sacred monster of the 20th century, and it makes us hope that this review of Puccini’s work will allow us to admire him again in the future, perhaps in a major exhibition that this time also compares him with his great references in Europe such as Monticelli, Gauguin and Van Gogh.

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.