In a two-year period in which numerous celebrations have been organized all over Italy for the five-hundredth anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci ’s death and just as many are expected in 2020 to commemorate the five-hundredth anniversary of Raphael Sanzio’s death, another anniversary has gone almost unnoticed: on January 24, 1920, Amedeo Modigliani (Livorno, 1884 - Paris, 1920) left us in Paris. Only Livorno, the artist’s hometown, wanted to commemorate the centenary of his death with a major exhibition dedicated to him, which can be visited until Feb. 16, 2020, at the Museo della Città.

Modigliani probably still carries the yoke of a tormented personality and rumors (truth?) about his bohemian conduct, as he is said to have been an immoderate user of alcohol and drugs; this is compounded by his untimely death at only 36 from tubercular meningitis, but which has actually hinted at a consequence of an over-the-top existence. A death that also dragged into tragedy his young companion, Jeanne Hébuterne, who, in despair, jumped from her bedroom window in her parents’ house the next day from the fifth floor in the ninth month of her pregnancy, causing the couple’s second child, whom she was carrying, to die as well. In the face of this, the idea of Modì as a cursed painter began to circulate, making the Modì - maudit assonance effective.

“How difficult it is, even today, to restore the reality of the character and the historical truth of the facts of that tragedy!” exclaims Marc Restellini, curator of the exhibition Modigliani and the Montparnasse Adventure. Masterpieces from the Netter and Alexandre Collections. Indeed, the intent of the Livorno exhibition is, in the words of the curator, “to restore Modigliani to his rightful place, that of one of the five geniuses of the century, an avant-garde painter and sculptor, as well as the inventor of a standard for the primitive arts along with Picasso and Matisse.” Restellini therefore asks, “what if history, not just the market, took advantage of this splendid opportunity to render him his rightful place?” Livorno, after all, has always been in Modigliani’s heart; their bond was always strong, even when the artist had moved to Paris, from 1906, but to his city he returned in 1909 and 1913. And once again the deep bond Livorno feels with its artist is made tangible through this major event.

As the title suggests, the exhibition is also an opportunity to present to the public the masterpieces belonging to the two most significant collectors who were part of Modì’s life: Paul Alexandre and Jonas Netter. The former was a young dermatologist who was already working in a clinic and, together with his brother Jean, destined to become a pharmacist like his father, decided to rent an abandoned cottage at 7 rue du Delta to house painters and sculptors, where they could work and live at a very modest cost. Real fixtures were organized here, such as “Saturdays of the Delta,” scenes of pagan dances, theatrical performances, music sessions, the Bal des Quat’z Arts, poetry meetings, and many other initiatives that made the fellowship and friendship between the artists grow more and more. Paul was passionate about art: from an early age, his parents had taken him to the Louvre to bring him closer to French art, and thanks to the Jesuit college he had met his first artist friends, including Maurice Drouard (1886-1915), Henri Doucet (Paris, 1856 - 1895), and Constantin Brâncuşi (Peştişani, 1876 - Paris, 1957), who in turn drew other artists into the group. These were different from each other, but were united by their financial support from Paul Alexandre and brothers Louis and Emmanuel Saint-Albin. Modigliani also later joined the circle, almost by accident: Paul had begun receiving patients at his clinic near rue du Delta, where he treated people from Montmartre. “It was exactly on the rue du Delta that I met him for the first time in 1907, and shortly after, also there, I introduced him to Brâncuşi,” Alexandre declared. In particular, it seems that their meeting had come about thanks to Doucet who frequented a cabaret in Montmartre, where numerous works by Maurice Utrillo (Paris, 1883 - Dax, 1955) were on display. Modì often frequented the cottage, bringing with him the necessities for painting and a few canvases, but he never settled here: he preferred to live in a hotel on rue Caulaincourt. A fine relationship of friendship and mutual esteem developed between Modigliani and Alexandre; suffice it to say that the rue du Delta house was wallpapered with the artist’s paintings, which is why jealousies soon arose among the rest of the group. Evidence of this can be found in a letter from Jean to Paul, dated April 1909, which reads, “The large room that I have provided to adorn with some Modigliani and photographs of Raphael is really splendid. From now on almost every panel will have at least one Modì. Doucet is furious, it’s my little revenge! He even put on a snout! And finally he saw that no one can stand him.” And from an account by Jeanne Modigliani, the artist’s daughter, it seems that one evening, drunk with wine and anger, her father destroyed some statues of Coustillier and Drouard because of an argument, and this caused the end of the rue du Delta era for the artist. Nevertheless, Paul and Amedeo remained friends: they spent hours discussing art, philosophy, and literature; Paul commissioned and bought works from him, given Amedeo’s precarious economic condition, and it seems that it was the latter who introduced the collector to African art and primitive arts, who then supported him in the creation of his caryatids. The relationship ended disappointingly toward Alexandre, however, when the latter left for war and Modì relied completely from 1914 on Paul Guillaume, an art dealer and great expert in so-called art nè;gre. Despite this ending, Alexandre owned a significant collection of the artist’s early works consisting of some twenty-five paintings and over four hundred drawings, but above all he had literally supported him and helped him gain artistic recognition.

|

| Images from the exhibition Modigliani and the Montparnasse Adventure. Masterpieces from the Netter and Alexandre Collections |

|

| Images from the exhibition Modigliani and the Montparnasse Adventure. Masterpieces from the Netter and Alexandre Collections |

|

| Images from the exhibition Modigliani and the Montparnasse Adventure.Masterpieces from the Netter and Alexandre Collections |

|

| Images from the exhibition Modigliani and the Montparnasse Adventure.Masterpieces from the Netter and Alexandre Collections |

|

| Images from the exhibition Modigliani and the Montparnasse Adventure.Masterpieces from the Netter and Alexandre Collections |

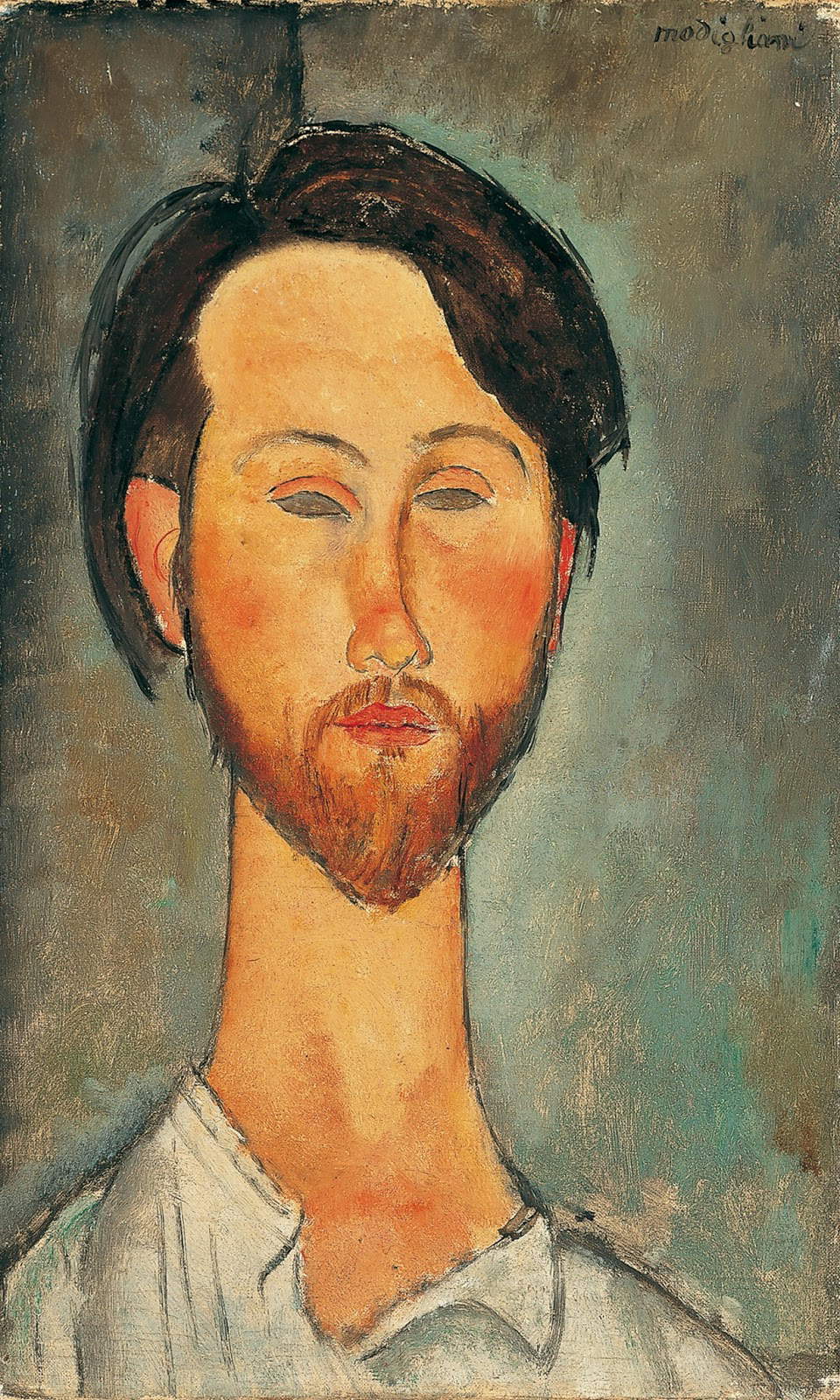

Instead, the meeting with Jonas Netter came about thanks to the Polish poet and dealer Léopold Zborowski: the two had met as a result of Netter’s encounter with a work by Utrillo in the prefect Zamaron’s office, a painting that had been sold to the latter by Zborowski. Thereafter, Netter entrusted the Pole with the management of relations with the artists, while, in a sort of collaboration, the former was responsible for settling salaries and expenses. Modigliani was thus the first artist to bind himself with an exclusive contract to Zborowski since 1916, breaking away for good from Guillaume, who showed himself more interested in his works than in the human relationship. It was thanks to the Polish merchant that Modì’s first major solo exhibition was held in 1917 at the Berthe Weill gallery, which was at the center of a scandal because of the display of many nudes in the window: even the police intervened and threatened to seize the works if they were not immediately withdrawn. In the following years Zborowski, with Netter’s support, had Modigliani’s paintings displayed in various exhibitions, at the Hill Gallery in London, at the Mansard Gallery and especially at a gallery on the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, where works by Picasso and Matisse were also on display, thus helping to circulate and publicize the Italian painter’s art.

When Modigliani died in 1920, Paris was in the midst of the so-called années folles, the years just after the end of the war, in which freedom spread on all fronts. Montparnasse, replacing Montmartre, became in particular the Parisian place of great cultural fervor, where people danced, had fun, and threw parties. The key word was “freely”: free love, free art. From the artistic point of view, however, the art dealers exploited Modí’s tragedy to raise the value of his works within the market, thereby contributing more, in their favor, to his figure as a cursed painter.

With the aim, as already stated, of the Livorno exhibition of restoring Modigliani to his rightful place through history, twenty-six of the artist’s works, including paintings and drawings, from the collections of Paul Alexandre and Jonas Netter have been brought together: specifically, twelve drawings from the former and fourteen works from the latter. Therefore, if one expects to visit a monographic exhibition, consisting entirely of Modì’s works, one is definitely mistaken in one’s approach, since the central part of the entire exhibition has been dedicated to them, we might say, and all around the visitors will be able to admire more than one hundred masterpieces, brought together by Netter since 1915, of the many artists who were part of theÉcole de Paris, that is, the wide variety of authors who found in the city of Paris, starting in the early twentieth century, the ideal place to express their art and creativity.

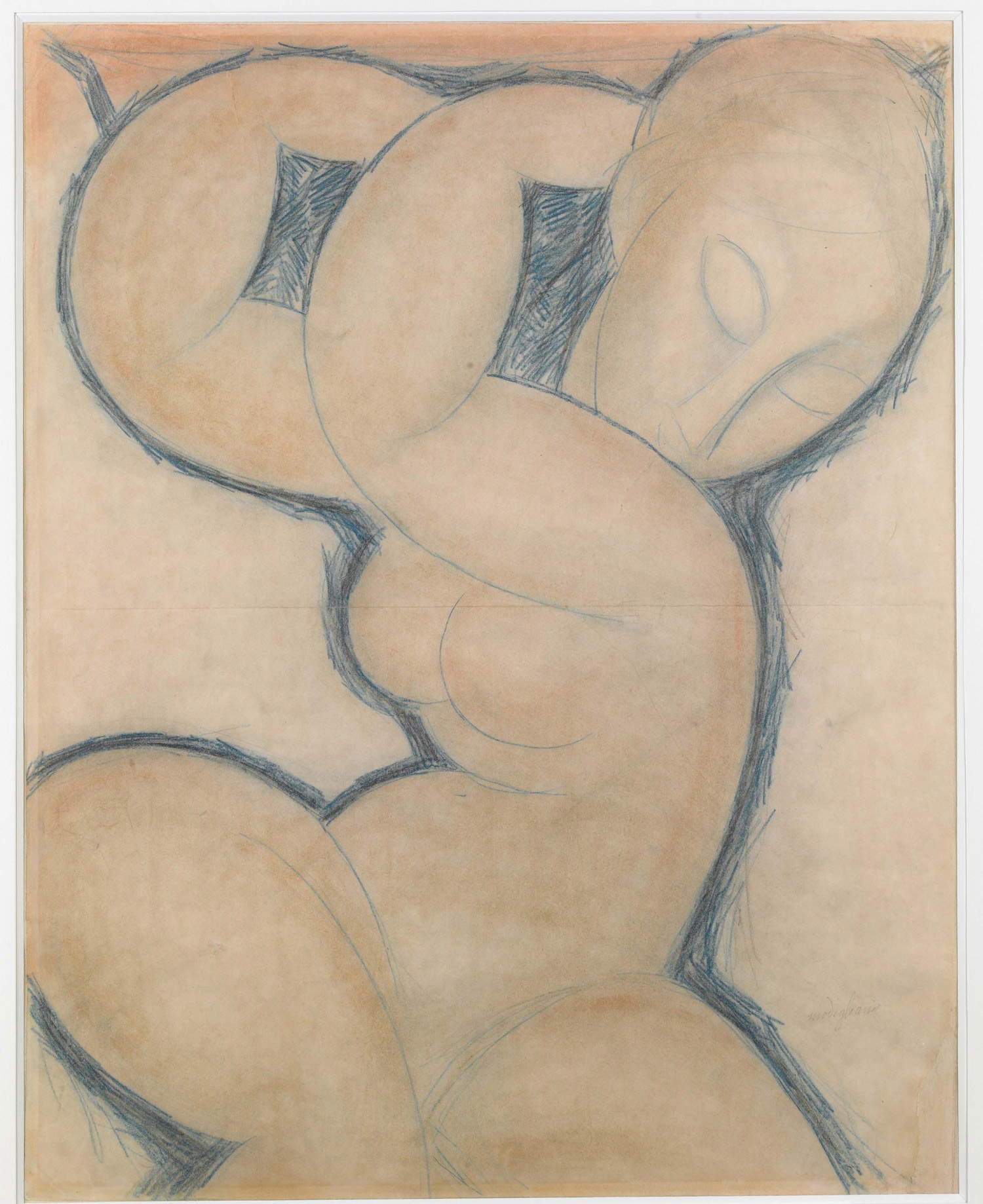

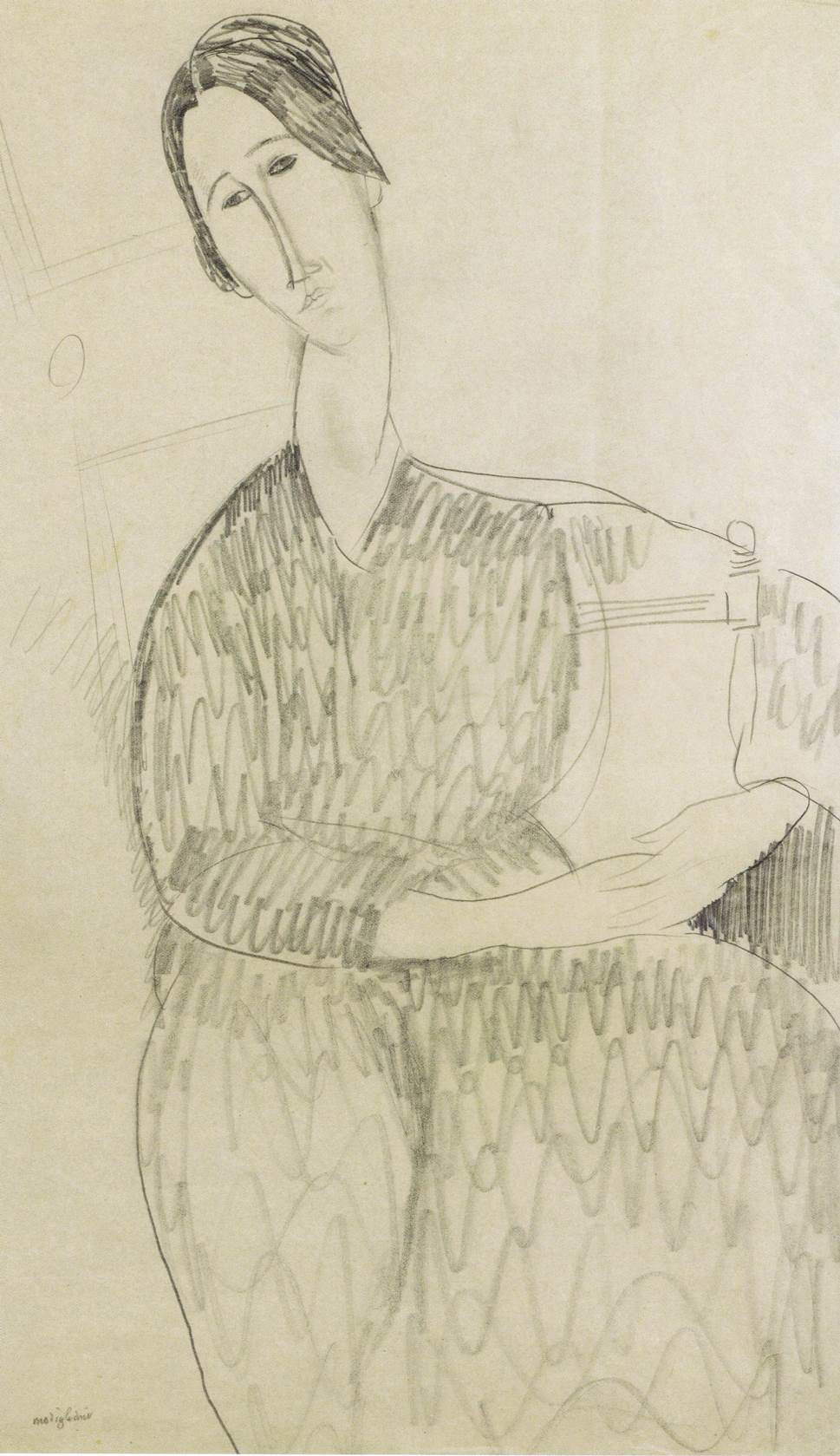

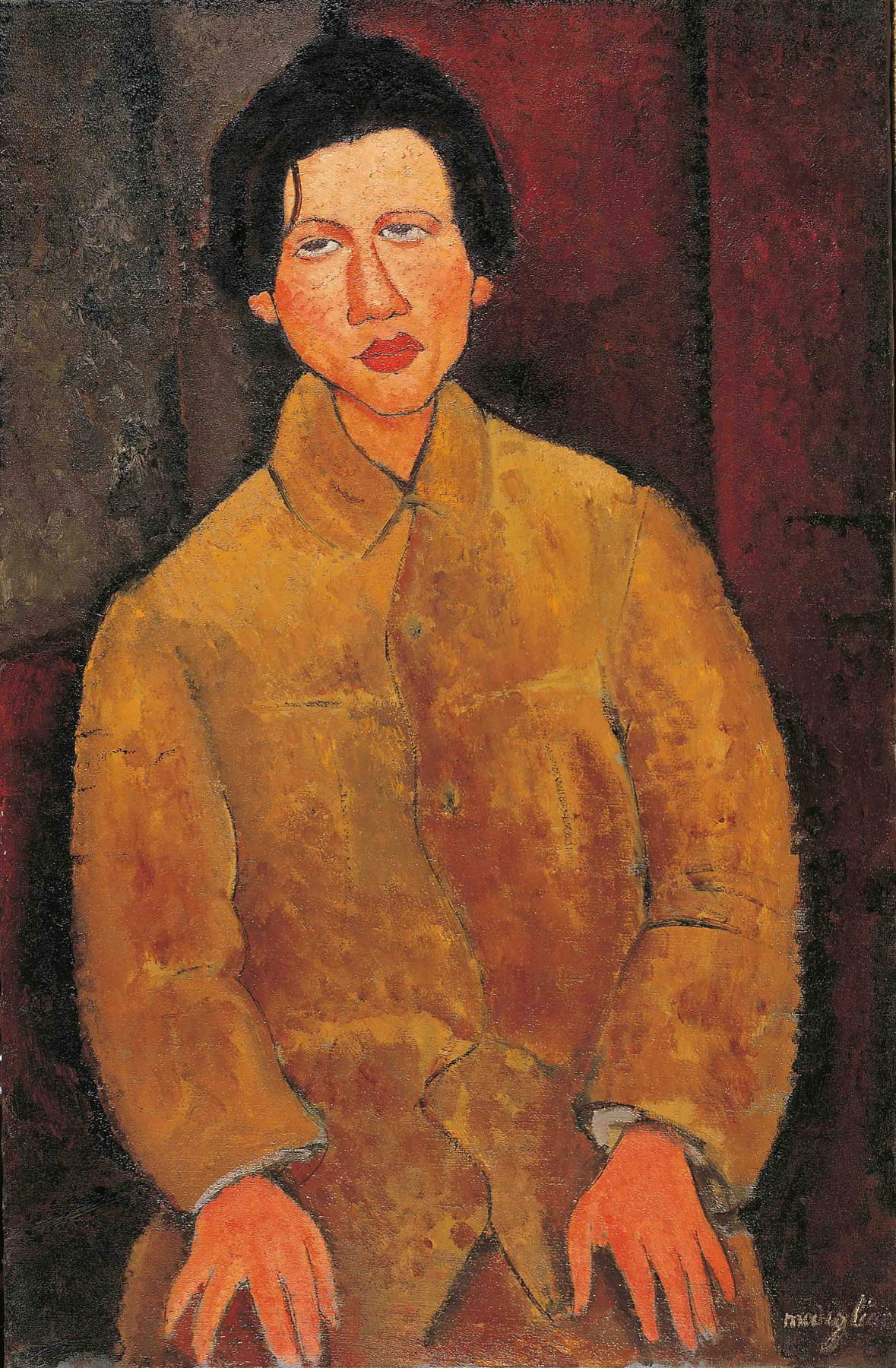

Among the masterpieces in the exhibition made by Modigliani are nudes and drawn and painted portraits, frontal and profile heads evoking African art, characterized by sharp faces with large, oval eyes, long noses and small mouths, and the ever-present caryatids, including the rounded and sinuous Caryatid (bleue) of about 1913 in blue pencil on paper. Recognizable in his portraits are Béatrice Hastings, the English journalist and poet who had an affair with Modì in the days of rue du Delta, the art dealer Zborowski and his woman Hanka Zborowska, the artist friend Chaïm Soutine (Smilovici, 1893/94 - Paris, 1943) and, of course, the young companion Jeanne Hébuterne depicted in Jeune fille rousse facing the viewer naturally and in Jeanne Hébuterne au henné. The only child, painted full-length, is the tender Fillette en bleu wearing a light blue dress, the color of her eyes.

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Cariatide (bleue) (ca. 1913; blue pencil on paper, 56.5 x 45 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Béatrice Hastings. Le menton appuyé sur la main droite (1915; oil on paper, 42 x 25 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Léopold Zborowski (1916; oil on canvas, 46 x 27 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Hanka Zborowska (1918; pencil on paper, 42 x 26 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Chaïm Soutine (1916; oil on canvas, 100 x 65 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Jeune fille rousse (Jeanne Hébuterne) (1918; oil on canvas, 46 x 29 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Amedeo Modigliani, Fillette en bleu (1918; oil on canvas, 116 x 73 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

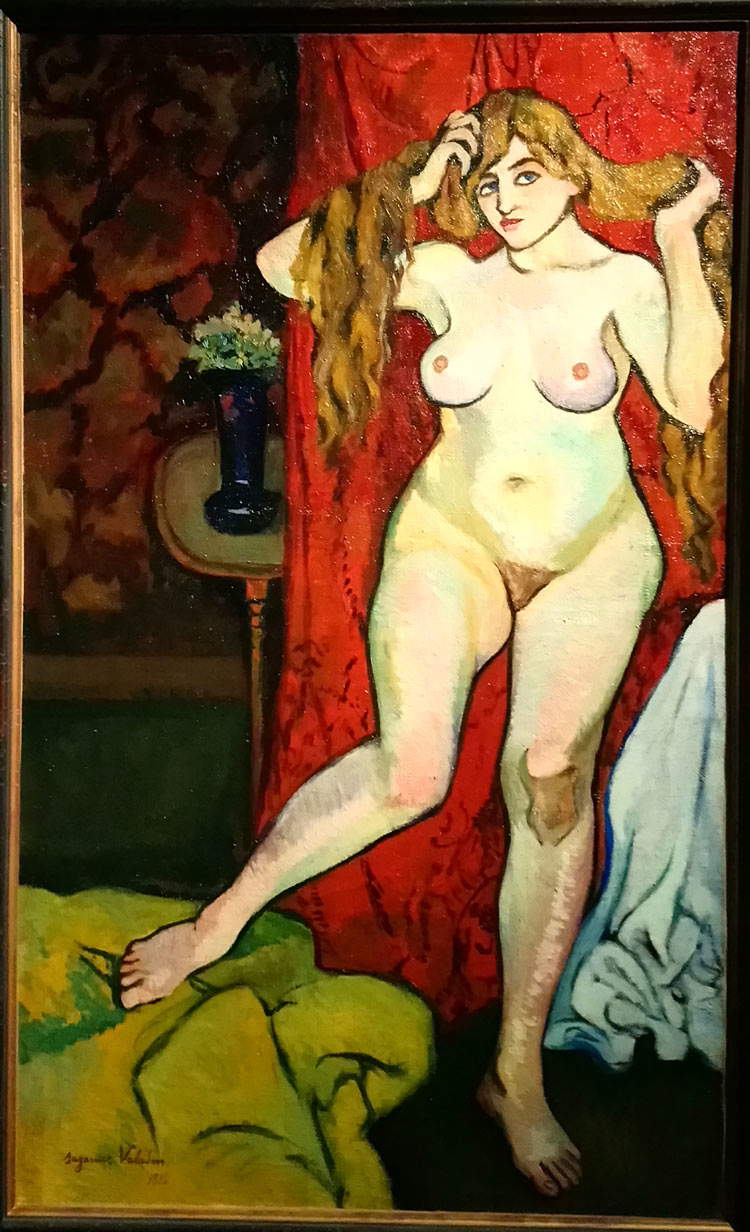

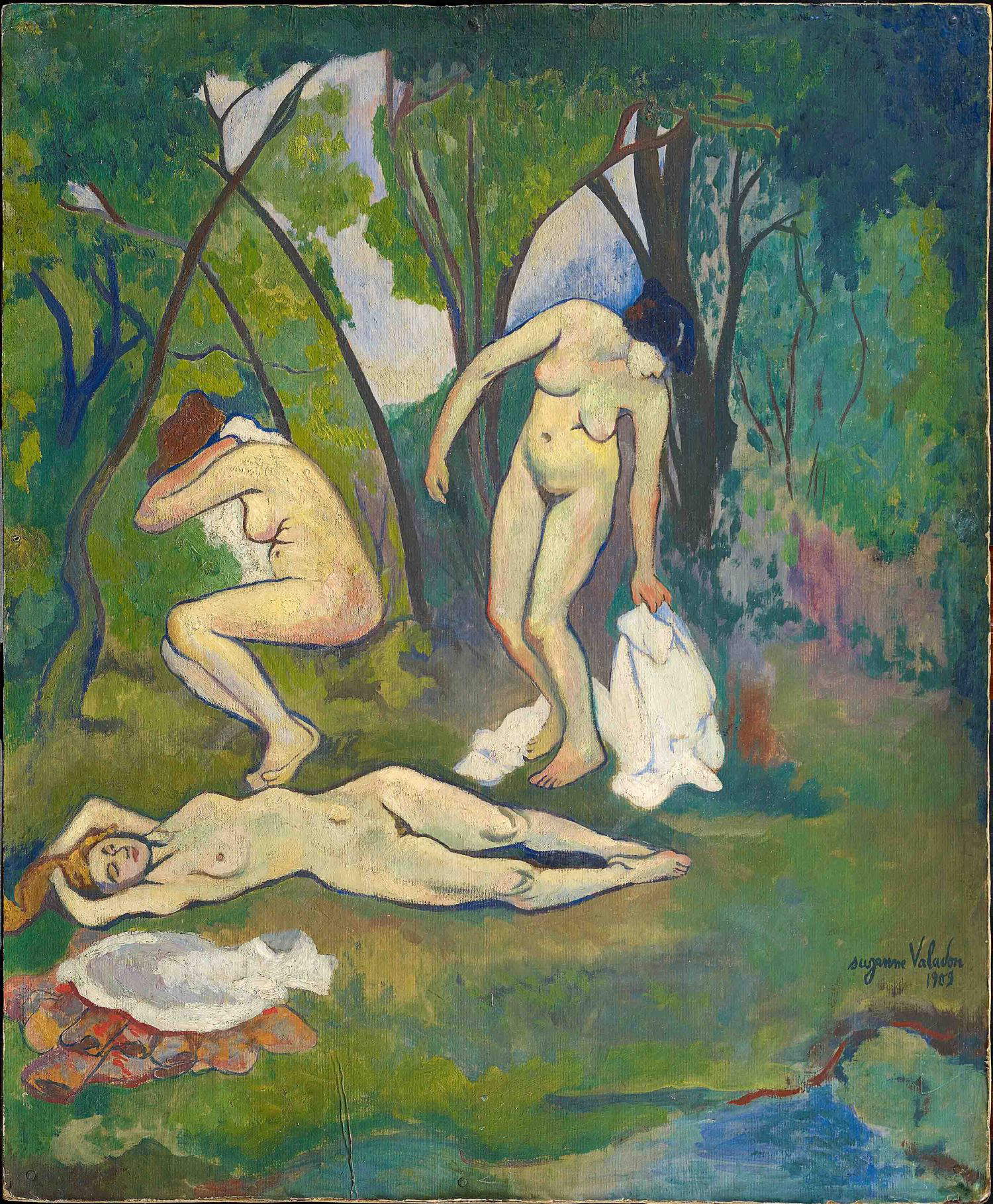

The exhibition opens with a remarkable selection of works by Suzanne Valadon (Bessines-sur-Gartempe, 1865 - Paris, 1938), no fewer than 12: in this body of masterpieces created by Maurice Utrillo’s mother, the visitor has the opportunity to go over the artist’s main themes, from female nudes portrayed in private settings or in verdant landscapes, as bathers, for example in Trois nus à la campagne or Nu se coiffant, to landscapes, views, still lifes and flowers. The shapely women depicted recall Gauguin, while the painterly energy with which he executes his paintings brings to mind Van Gogh. Suzanne, her son and companion André Utter, Maurice’s friend, were nicknamed la trinité maudite because of the life of excess they led: sales of Utrillo’s works were going great, but the latter had some problems withalcohol; he drank and therefore often found himself in the hospital or at the police station. His works, mostly landscapes, neighborhood streets and churches, immortalize Montmagny, where he lived as a child, Montmartre, where he later settled, and other suburban corners where human presence is all but absent.

Gauguin’s influence is still felt in Les Grandes Baigneuses by André Derain (Chatou, 1880 - Garches, 1954), both in the colors and in the reference to exotic depictions.

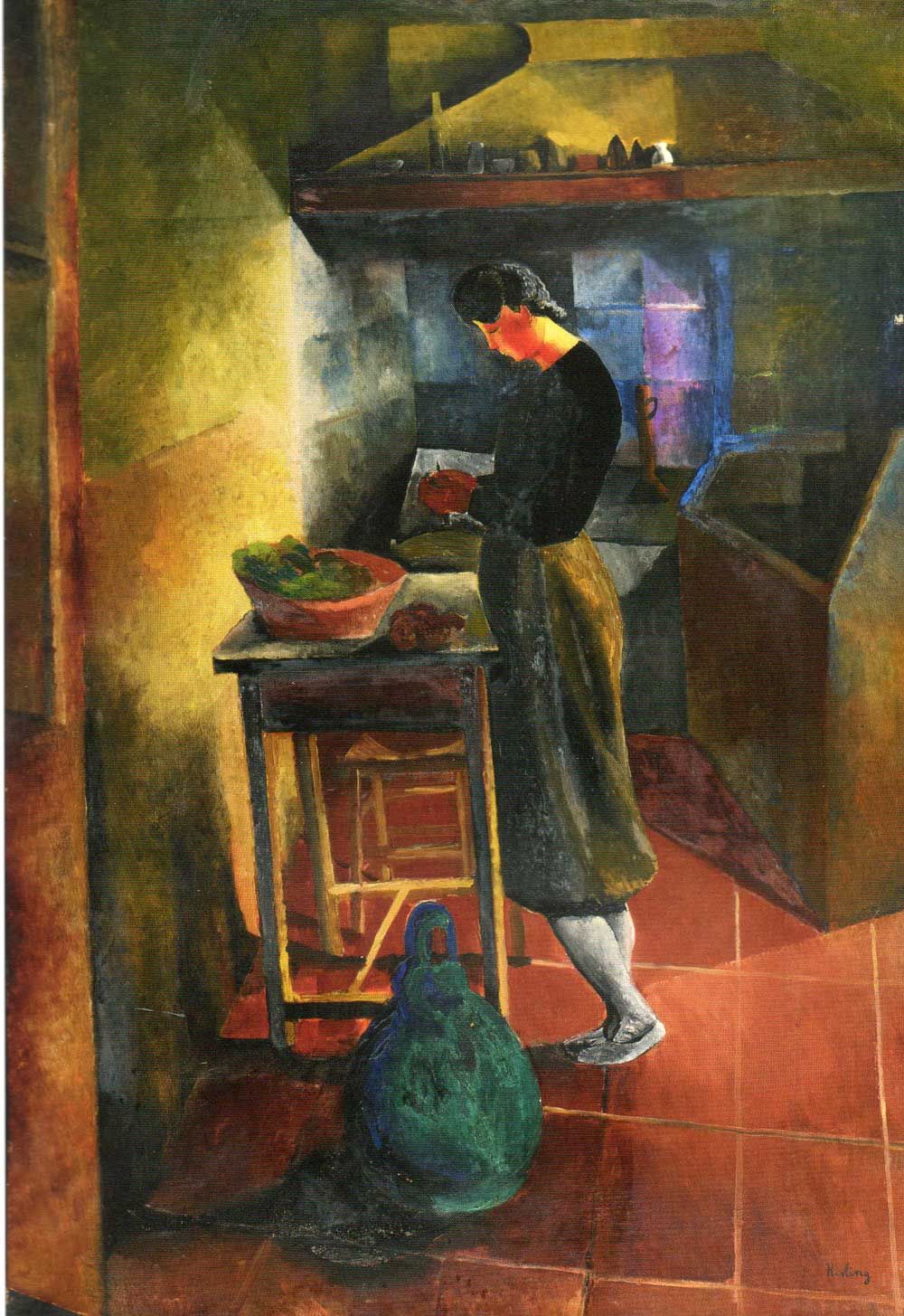

The Polish artist MoïseKisling (Krakow, 1891 - Sanary-sur-Mer, 1953) had also moved to Montparnasse : he painted in a studio open to all, always crowded, but when his model arrived, he was always ready to portray her in one of his works. Modigliani also visited him every day in his studio, and here they worked together, with the same model. Every Wednesday he would invite painters, writers, musicians, and politicians to lunch, and after lunch they would discuss various topics over a glass of armagnac. Initially influenced by Cézanne, Kisling chose to adopt brilliant painting; he is said to radiate energy, mixing life, love, sensuality and painting. The artist wanted to capture the splendor of the moment, and sound tones, imbued with light, predominate in his paintings. He painted everywhere, mostly nudes, but also children with nostalgic expressions, landscapes, still lifes and flowers.

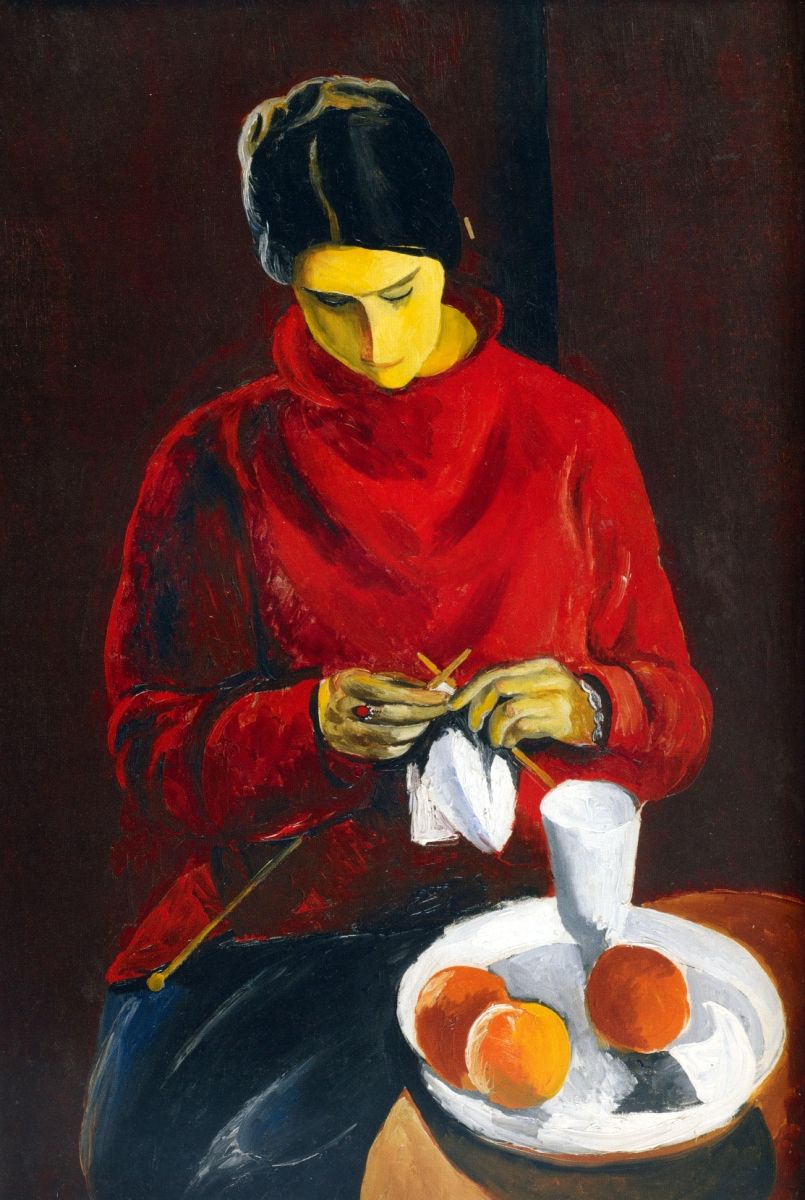

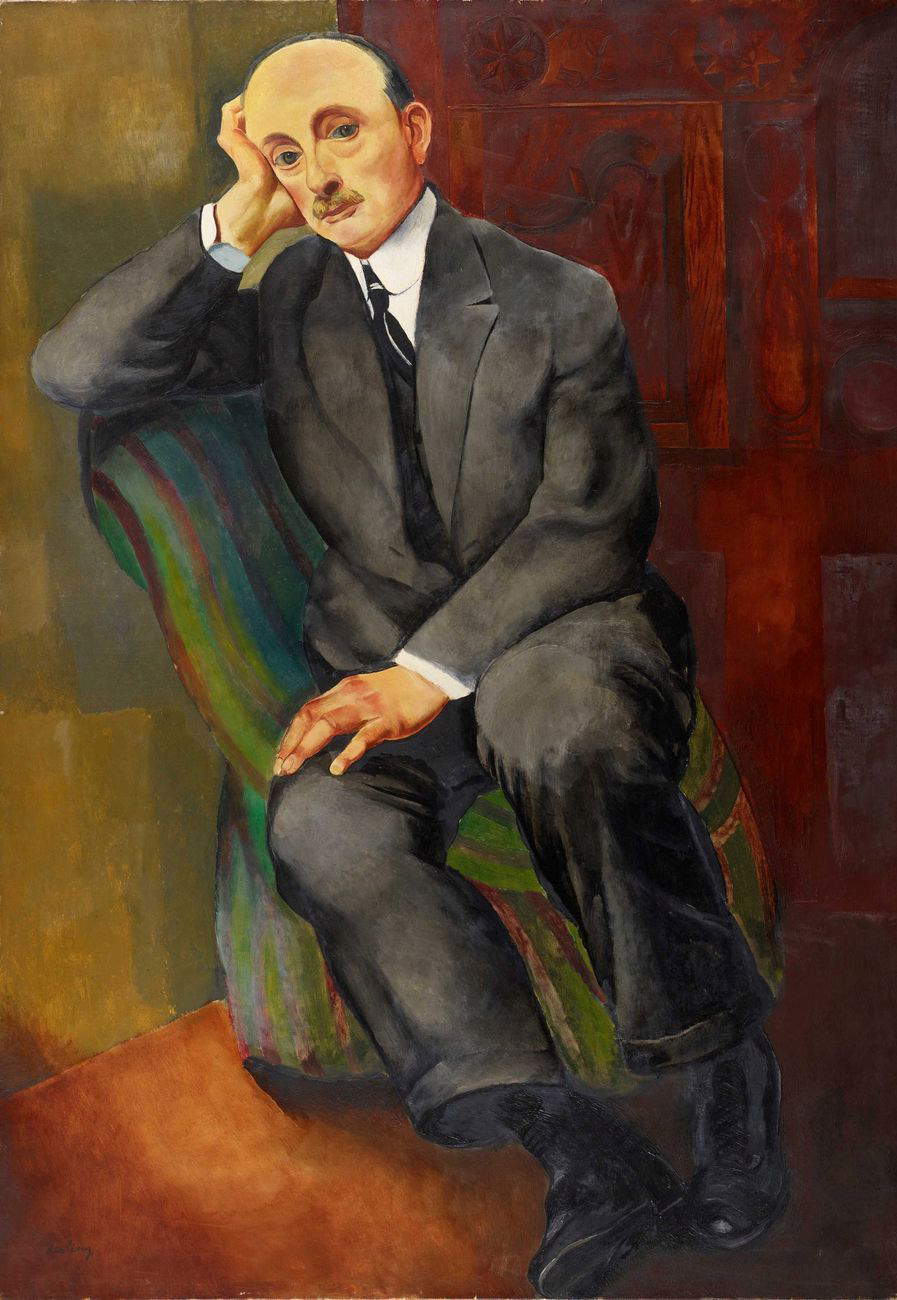

His vibrant colors strike the eye of the viewer, in works such as La femme au pullover rouge, where a brunette woman, concentrated in her work, wears a beautiful red sweater that stands out on the entire canvas, or in La jeune cuisinière, where brown, yellow, red, purple, and green create particular and striking color contrasts. True plays of color that also enhance a sea with boats in the foreground, as in St-Tropez, Septembre. In addition, Kisling made an almost photographic portrait of Jonas Netter, a painting that became part of the latter’s own important collection.

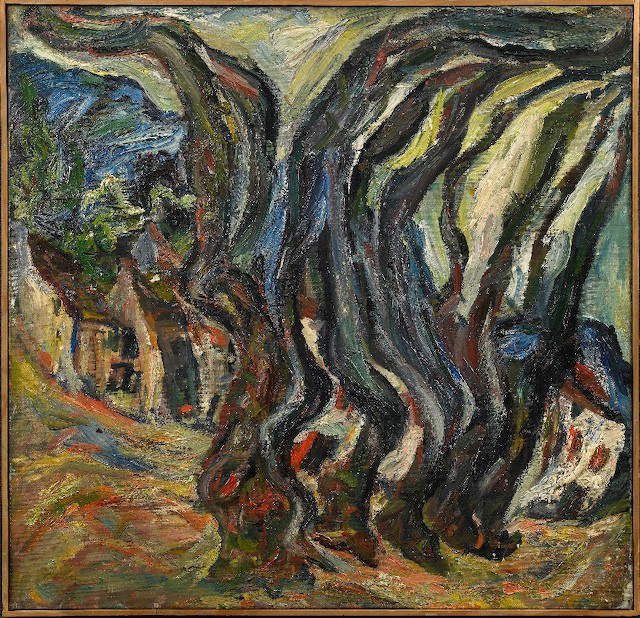

A strong bond of friendship then bound Modigliani to the Russian artist ChaïmSoutine: for the latter Modì was an ideal model, and vice versa Modì appreciated Soutine’s talent. It was the painter from Livorno who brought his friend together with Zborowski, who, however, was not fascinated by either the person or his art. However, before he died, Modì entrusted him completely to the merchant’s support, although this was very limited. Zborowski did not believe in his talent and, for his part, Soutine is said to have been neurasthenic, sickly, hypersensitive, shy, and prone to fits of rage and fixations. He used to create his works in a state of feverish inspiration, but, constantly dissatisfied, he himself often destroyed his earlier paintings. As the French art critic Raymond Cogniat stated, there was “not an indulgent or tender image, an affectionate smile, to be found in his work, in that game of his massacre, just as in his restlessness there was never any rest, even when circumstances permitted. Ugliness was his terrain, restlessness his climate, passion his permanent state.” A description that is fitting when looking at his works, such as La Folle, Femme en vert, but also his landscapes that convey restlessness and torment, such as Les grands arbres bleus or Paysage montagneux, and the quartered flesh of Le Boeuf. But a sense of disquiet also pervades the paintings of Maurice de Vlaminck (Paris, 1876 - La Tourillière, 1958), especially the somber tones and depictions of landscapes in the midst of a storm.

|

| Suzanne Valadon, Nu se coiffant (1916; oil on canvas, 100 x 61 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Suzanne Valadon, Trois nus à la campagne (1909; oil on cardboard, 61 x 50 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| André Derain, Les grandes baigneuses (1908; oil on canvas, 178 x 225 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Moïse Kisling, La femme au pull-over rouge (1917; oil on canvas, 93 x 65.5 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Moïse Kisling, La jeune cuisinière (1910; oil on canvas, 130 x 89 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Moïse Kisling, Portrait d’homme (Jonas Netter) (1920; oil on canvas, 116 x 81 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Moïse Kisling, St-Tropez, Septembre (1918; oil on canvas, 65.2 x 54.2 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Chaïm Soutine, La folle (c. 1919; oil on canvas, 87 x 65.1 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Chaïm Soutine, Les grandes arbres, Céret (c. 1922; oil on canvas, 66 x 64 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

|

| Chaïm Soutine, Paysage montagneux (ca. 1920; oil on canvas, 85 x 74.8 cm; Jonas Netter Collection) |

Numerous other artists belonged to theÉcolede Paris, each with their own pictorial characteristics, one different from the other, producing in Paris one of the greatest varieties of paintings that ever existed in the same time frame. In the last part of the exhibition, the visitor will find a roundup of artists who are little known, if not unknown compared to authors such as those mentioned above, but who populated the Parisian artistic milieu at that time, in their own way therefore important for an overall understanding of the context in which Modigliani was cast. Therefore, still lifes by Henri Hayden (Warsaw, 1883 - Paris, 1970), the Portrait de femme by Adolphe Feder (Odessa, 1886 - Auschwitz, 1943 ?), a landscape with a house behind trees by Renato Paresce (Carouge, 1886 - Paris, 1937); works united by the full Cubist influence. Closer to Van Gogh and Cézanne are the paintings of Pinchus Krémègne (Zaloudock, 1890 - Céret, 1981); and again, on display are landscapes, nudes, portraits by Jan Waclaw Zawadowski (who signed himself Zavado under Zborowski’s suggestion), Isaac Antcher with his trees (Peresecina, 1899 - Malakoff, 1992), by Gabriel Fournier (Grenoble, 1893 - Fontainebleau, 1963), by Eugène Ébiche (Lublin, 1896 - Warsaw, 1987, by Zygmunt Landau (Lodz, 1898 - Tel-Aviv, 1962). And even compositions by Jean Hélion that hark back to Mondrian.

Among the merits of this major review is that it also presented a broad perspective of that environment and those years; a range of artists who made Paris the hub of art par excellence, where diversity bore positive fruit.

In the exhibition catalog, in addition to essays dedicated to the two valuable collectors Netter and Alexandre, all the artists who took part in the Montparnasse adventure are illustrated, each with his or her own biography.

The stage of honor, however, belongs to Modigliani, and it is hoped, thanks to this exhibition, that his figure will be appreciated more and more for what he produced in his art rather than for the imagery that was created around him.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.