It is among the words of Ólafur Elíasson himself that one needs to find the most interesting elements of his large-scale solo exhibition Nel tuo tempo (In Your Time), the long-awaited event that Palazzo Strozzi is dedicating to the Danish-Icelandic artist, offering an exhibition that offers the public a mélange of historical works and works specially created for this occasion. In this mixture lie some important critical elements, starting with the fact that the exhibition renounces precise self-definition, preferring to present itself, if anything, as, quoting from the press notes, “the largest exhibition of Ólafur Elíasson ever held in Italy.” the nature of the rooms of Palazzo Strozzi, a Renaissance building, perforce forced Elíasson, curator Arturo Galansino and their collaborators to invent a review that, if it must be considered a retrospective organized according to criteria of philology, suffers from a few too many weaknesses. In particular, the visitor who knows nothing about Elíasson’s art will be confronted with an itinerary that is not very organic and that helps little in understanding the development of his art from a diachronic perspective. It has, if anything, the character of an anthological exhibition: some of the works that best marked Elíasson’s artistic journey have been chosen, in a manner that is not exhaustive, not complete and perhaps not even too representative, and they have been arranged according to the possibilities offered by an ancient, fascinating and complex building such as Palazzo Strozzi.

Ancient building that represented, therefore, the main challenge for Elíasson, and in his response lies the main reason for interest in the exhibition, seeing it from the perspective of those who will not go to Florence completely unfamiliar with his art (for those who do not know Elíasson, however, the exhibition represents a very significant opportunity). His idea, the artist informs us in the text written for the catalog, was to conceive of Palazzo Strozzi “not so much as a passive host, as a backdrop, or even a container for the exhibition, but rather as a co-producer of the exhibition itself.” Elíasson calls up a number of quotations from texts by contemporary academics to support his project: the underlying idea is well expressed by a passage by geographer Doreen Massey, who asks the reader to imagine a journey between Manchester and Liverpool. While we are on the road, neither city will remain identical to itself, neither will remain passive to greet us to welcome us, but both will move forward, as will the tens of thousands of stories, lives, trajectories that intertwine in their streets, inside their buildings. The metaphor comes in handy for Elíasson to explain that Palazzo Strozzi, too, comes down to us after making “a journey through time from its origin in the Renaissance as a palace owned by the powerful Strozzi family, to its present role as a space that hosts research centers and exhibitions.” The visitors themselves, to go to the exhibition, made a journey, their stories intersecting with those of many other visitors who set out with the same goal to meet at Palazzo Strozzi.

The first work the visitor encounters on the journey, Under the Weather, is intended to be a metaphor for this encounter between palace and visitors: a large suspended ellipse that, through the moiré effect (the one, in short, that is obtained by superimposing two equal textures at different angles), aims to create “a perceptual displacement through a game of visual interferences” to destabilize “the impression of the rigid orthogonal architecture of Palazzo Strozzi, questioning its perception as a stable and unchanging historical structure” (so Galansino in his text). Of course, it would be reductive to limit the significance of this work, and even more so of the three that are located on the main floor and interact with the architectural elements of the building, to the role of a reminder to the public that Palazzo Strozzi is not a structure that has remained unchanged over time: or at least, it would make little sense in the most stratified country in the world, where citizens are accustomed to live, study, work, eat, entertain, and reproduce in urban fabrics filled with historical evidence from every era from the ancient Greek colonies onward, and moreover in a building where every intervening artist has wanted to leave his or her mark with equally monumental installations. One need only think of the recent slides that Carsten Höller installed in the courtyard of Palazzo Strozzi, but the journey back in time can touch on even more distant stages.

One could therefore open a parenthesis and go back to the 1960s, and in particular to a series of exhibitions that were held at Palazzo Strozzi, all of which were set up by the Florentine Leonardo Savioli, a visionary architect and pupil of Giovanni Michelucci, who saw in the design of the installations themselves a moment of extraordinary and intense creativity. For the great exhibition on Le Corbusier that was held at Palazzo Strozzi in 1963, a problem characterized by several orders of complexity had arisen: to make the ancient palace dialogue with the modern works of the Swiss architect, to propose to the public an exhaustive testimony of Le Corbusier’s painting and sculpture (this had been his express request for agreeing to the project), to coherently tie the objects to the structures of the palace. The problem before which Savioli found himself was not far from the one facing Elíasson today: “finding myself in the condition of having to exhibit new objects in ancient buildings, I felt,” Savioli would later say, “that the new object, if it is true, is sum, is continuity, is ’history,’ and therefore as such could perfectly approach a capital, a portal, an ancient space. It might have seemed like a stretch, at least initially, which, however, then turned out to be an authentic continuity, even though more than four centuries had passed between Le Corbusier’s painting, for example, and the capital of Palazzo Strozzi: four centuries that, with careful juxtaposition were annulled, pulverized, a kind of ’short circuit’ between objects four centuries apart and never seen together before.”

The arrangements thus maintained a precise line: trivializing, a basic “Cartesian rigor” (so Lisa Carotti) to emphasize the modernity of Le Corbusier’s work, panels, bases and platforms that seemed like objects in their own stand-alone to convey the idea of the connection of the various souls of the great architect’s research, structures well spaced from the walls of the building to suggest temporal distance, but also, quoting Carotti again, sculptures “isolated and transformed into compositional fulcrums,” “exhibition supports worked as sculptural objects,” “paintings treated as three-dimensional objects and detached from the wall,” and “doorways transformed into frames” to make evident the “short circuit” to which Savioli alluded. And again Savioli took part in an even more radical experiment, the exhibition La casa abitata, which, in 1965, under the organization of a committee chaired by Michelucci, invited fifteen architects to Florence (including Ettore Sottsass, Angelo Mangiarotti, Marco Zanuso, the Castiglioni brothers, Leonardo Ricci, Vittorio Gregotti, and Savioli himself) to think about the theme of living: the rooms of Palazzo Strozzi were transformed into living units, dining rooms, living rooms, bedrooms, bathrooms to show the public the most innovative ideas about the home.

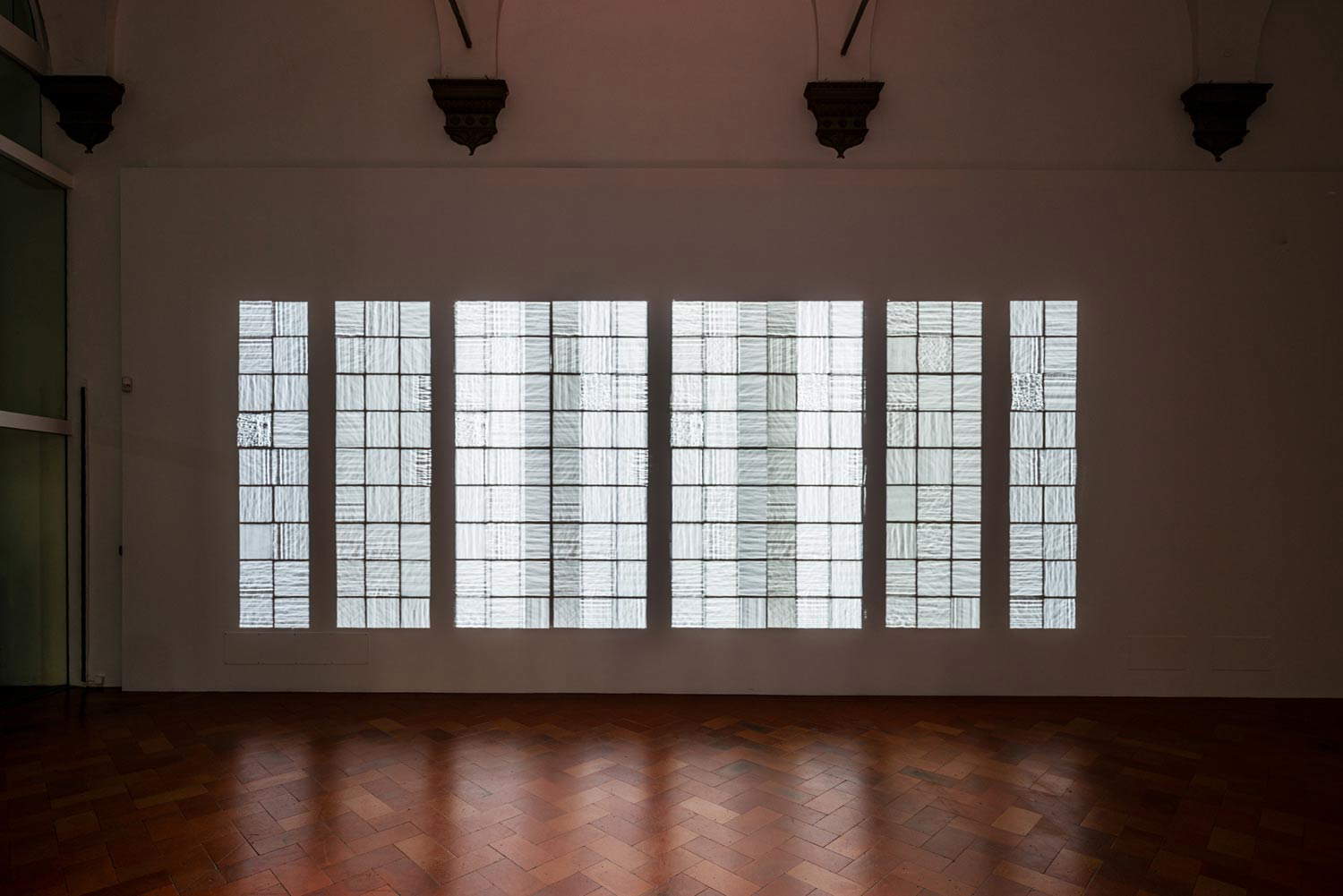

In essence, the public at Palazzo Strozzi has been accustomed to experiments that alter their perception of the building for sixty years: it happens, one might say, for virtually every exhibition. More interesting, if anything, is the reflection that Elíasson opens up on the value of Palazzo Strozzi, introduced by Under the Weather itself but even more so by the three works on the upper floor, all similar, all in the first three rooms. The first one one encounters is Triple seeing survey: the light projected by three spotlights set up in the courtyard filters through the Palazzo Strozzi’s large windows and creates like doubles on the wall, complete with a reproduction of the irregularities of the material. Of the triptych it is perhaps the most striking work: the room is transformed into a kind of gallery, a covered loggia, the appearance of the environment is heavily altered. In the next room, however, is Tomorrow: the principle is similar, but the light comes from outside and is colored through special filters to offer the audience the suggestion of a sunrise or sunset. With even a slight sensation of estrangement: “When they enter the room,” the catalog reads, “visitors can make out the silhouettes and ankles of the people on the other side of the screen but do not understand how to access this second space until they push further along the exhibition path. The work [...] reflects Elíasson’s deep interest in the decomposition of white light into its different wavelengths.” Finally, we arrive in front of Just before now: still playing with reflections with the windows of the building, but this time with overlapping blue and orange filters and irregular grids.

Ólafur Elíasson intervenes in the spaces of Palazzo Strozzi, altering their appearance, changing their form, extending or shrinking them, all through window projections, to create a new shared space, starting with a thought by African American writer and history scholar Saidiya Hartman: “Every generation faces the task of choosing its past. Legacies are chosen as much as they are passed on. The past depends less on ’what happened then’ than on the desires and discontents of the present.” The idea is that an object that comes to us from the past does not represent a generic “past” as much as, if anything, the visions and ideas that animated, at that given moment in history, the people who participated in the making of that object. “Palazzo Strozzi itself,” Elíasson concludes, “tells us a story about architecture employed as an instrument of power.” Deconstructing this architecture, disorienting the viewer, forcing him or her to act, albeit unconsciously, in the first person (in Tomorrow and Just Before Now we see the shadows cast by visitors standing on the opposite side of the room: the drapes on which the lights are projected are arranged in the exact center of the room), Elíasson evidently aspires to make manifest the sense of passing time (hence the title of the exhibition) and, consequently, to highlight how the value of Palazzo Strozzi has changed over the centuries. From a hub of power to a founding nucleus of new experiences, a center of research, a place for sharing. “One can be immersed body and soul in a situation and at the same time reflect on this immersion, that is, critically evaluate what one is doing while one is doing it”: thus Elíasson, who reasoning on this assumption also motivates the centrality that body and movement assume within the experience he intended to build for the public. The fluidity of perception is, moreover, central to his research; his text in the catalog emphasizes this concept several times, and the works that follow could be understood as a way of reiterating it, even if the apparatuses struggle a bit to make the visitor educated about the philosophical basis of Elíasson’s art, focusing more on the external effects of his installations, a situation that increases the perception of walking through a kind of mirror maze.

The remaining rooms of the exhibition thus proceed in a path through some of Elíasson’s historical and recent installations: it begins with How do we live together, the large mirror-mounted arch hanging from the ceiling that on the one hand offers the illusion of an enormous ring occupying the room, and on the other extends the physical space by the means of reflection, offering an additional sense of displacement to the audience. We then move on to the string of light installations, which bring to mind Lucio Fontana’s revolutionary environments: Solar compression, Red window semicircle and Triple window lead inside rooms where spotlights project colored lights into the space creating different and surprising effects. The most spectacular passage in the exhibition is the one that leads toward Beauty, one of Elíasson’s earliest works, as well as among his most original works: in the center of a gloomy room, a pump creates an artificial fog on which is reflected a rainbow that changes according to the perception of the audience moving within the environment, with the aim, Elíasson himself explains, “of swinging back and forth between two positions: seeing the rainbow, not seeing the rainbow, seeing and not seeing.” We finally reach the last two rooms on the main floor, first with the kaleidoscopic installations Firefly double-polyhedron sphere experiment and Colour spectrum kaleidoscope, and then move on to Room for one color, the “yellow room” reminiscent of Bruce Nauman’s Yellow room. Descending into Strozzina, one will encounter another new work, Your view matter, a virtual reality installation that transports the audience into spaces constructed by exploring the possibilities of Platonic solids (tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron and cube) and the sphere, ending with other works that make use of mirrors: City Plan, on the theme of the flow of information (a series of mirrors reflects the daily changed front pages of some local newspapers putting the viewer in the center of the space created by the refractions), Eye see you, another work that makes use of the moiré effect , and Fivefold dodecahedron lamp, a dodecahedron containing a tetrahedron that, by means of mirrors and a halogen bulb, casts games of reflections and shadows.

Those who, from the Florentine exhibition, were expecting radical, highly innovative new works that would give Elíasson’s work a further twist, perhaps prompted by the urgent contingencies of our time, as Elíasson is an artist with a strong interest in topics such as climate change, inclusion, and relationships with others, will probably be disappointed: the new works made for Palazzo Strozzi, if we consider them from an eminently artistic point of view and without therefore charging them with the value they take on in relation to the place that contains them (and precisely because they are so tied to the building are works that we will never see again, except in a second Elíasson exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi, who knows if and when), they do not have this character; on the contrary, they recall the Scandinavian artist’s earliest experiences, ever since the first Window projection in 1990, executed by a barely 23-year-old Elíasson. The new works, however, extend the possibilities of those early experiments: at Palazzo Strozzi, the path begun by Elíasson more than 30 years ago aims, with the use of the same means, to make us mature in our awareness of the places in which we live. And yet, since it is also the “largest Ólafur Elíasson exhibition ever held in Italy,” it would also be interesting to open a discussion on the consistency of Elíasson’s debt to Italian art.

It is not just a matter of discussing the correspondences his installations find in the paintings of Renaissance artists, a topic on which Galansino (who is an art historian) focuses excellently in his catalog essay, urging us to note additional reasons for interest in works such as Triple seeing survey, Tomorrow and Just before now: from the perspective geometries of Paolo Uccello to the experiments of Leonardo da Vinci via the “light painting” of Beato Angelico and Piero della Francesca (Galansino, for example, introduces a parallel between the light beams of Triple seeing survey and earlier works, such as Love sees with eyes, not with mind of 1999, and the atmospheric dust of Piero della Francesca’s Madonna di Senigallia ). It is also a matter of reasoning, in addition to the possible debt to Fontana briefly alluded to, about the suggestions kinetic art, and in particular the work of Group N, starting with Alberto Biasi and Manfredo Massironi, may have provided to Elíasson, a subject little or not at all addressed and which the exhibition does not touch upon: Biasi, Massironi and others were already making moiré-effect works decades ago ; Biasi’s environmental work Tu sei anticipates Elíasson’s Uncertain shadow by some forty years (a filiation, moreover, acknowledged in the second of the two volumes accompanying the exhibition The Eye at Play currently running at the Palazzo del Monte di Pietà in Padua until Feb. 26), the spheres of Your timekeeping window seem to derive from Edoardo Landi’s Variable Spherical Cineriflexion, not to mention, of course, the environmental works of Group N or, even more specifically, Alberto Biasi’s projections of light and shadow from the early 1960s that could be counted among the most natural antecedents of Elíasson’s works with light.

Returning instead to the conceptual value of Elíasson’s art, to conclude, what is our time? The exhibition, pulling together and wanting to find an overall meaning, would seem to be a continuous answer to this question: for Elíasson, our time is first and foremost a shared time, made up of individual and collective perceptions, memories, thoughts. It might sound trivial, but the center of Elíasson’s argument is relevant: it implies a reflection on the concept of the “global we” on which Elíasson has worked several times in the past and which the artist now, however, declares that he wants to revise in light of the fact that exceeding in universalizations might be unreasonable as well as ill-suited to respond to the challenges of the present. It is probably on these ideas that Elíasson’s work will be oriented in the future.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.