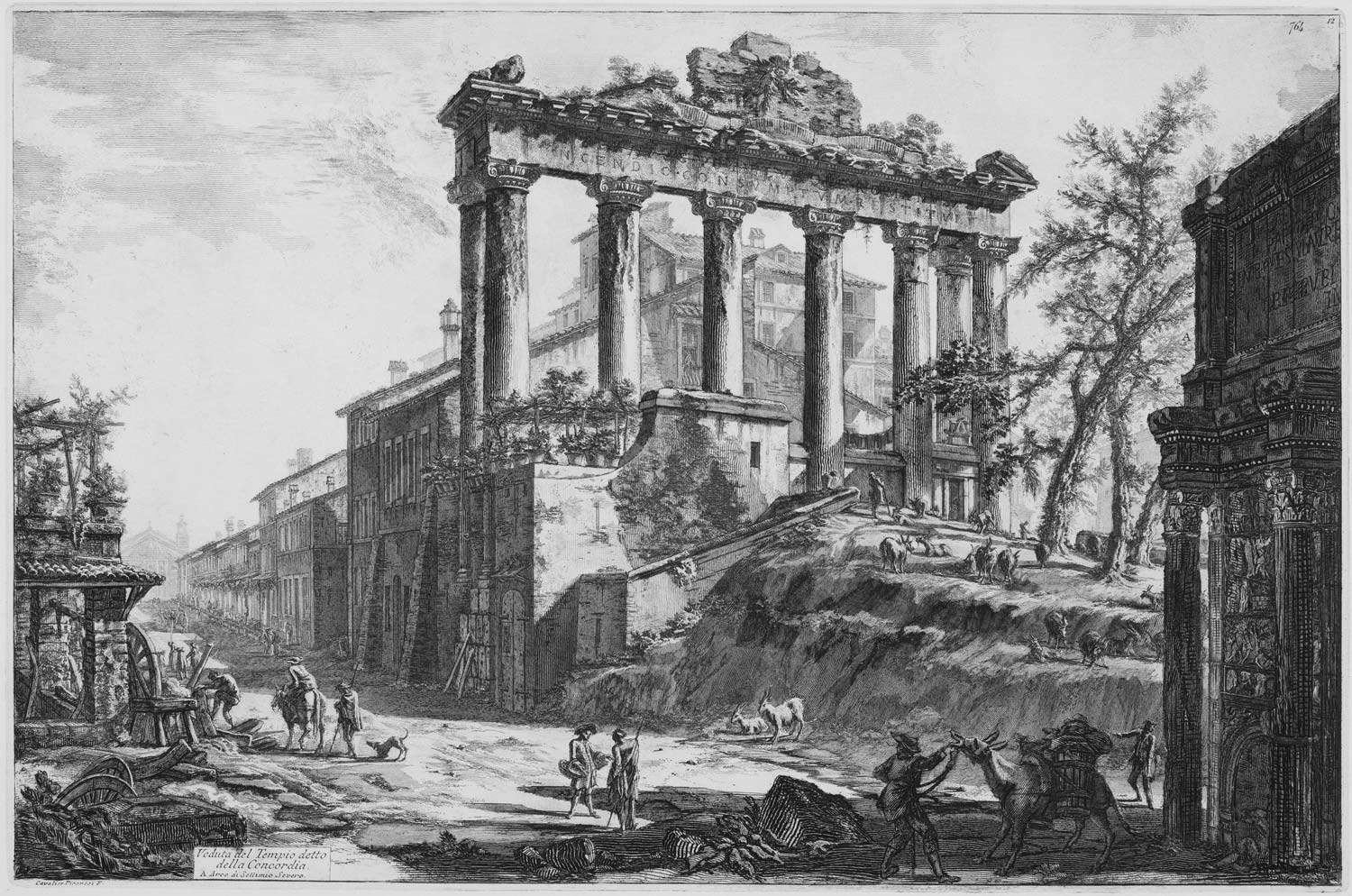

In front of their eyes the imposing and threatening mass of the Alps, in their hearts the longing for the eternal Urbe, in their minds the images they saw at home while leafing through Piranesi’s Views of Rome. We can imagine them this way, the travelers who descended slowly on the Italian peninsula from northern Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries: the Grand Tour always began after reading, after studying, after dreaming. And among the volumes that contributed to feeding the myth of Rome and its antiquities, a not secondary role belonged to the collections of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, which enjoyed an extraordinary fortune: success arisen in particular from the aforementioned Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome ), which, started around 1747, were continued by the artist until the last years of his career, with new plates being added almost annually. Sold individually or in fascicles, they exerted, Fernando Mazzocca has written, “a decisive influence on the formation of a romantic conception of classical antiquity, conditioning our ideas about Roman civilization.” There are, in all, one hundred and thirty-eight plates: the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia is among the institutions that possess the complete collection. And the Umbrian museum, meritoriously, decided to pull it out of storage, have it restored, and exhibit a selection, of sixty-one pieces, until next January 8, 2023, in an exhibition entitled Piranesi in the Collections of the National Gallery of Umbria, curated by Carla Scagliosi.

The two volumes of the Views in the museum’s possession were pulled after the disappearance of the great etcher, but from the original matrices, those of the Piranesi Chalcography, acquired by the Parisian printer Firmin Didot Frères in 1834 (Piranesi’s sons, Francesco and Pietro, had moved to Paris since 1799 after the events of the Roman Republic), only to be transferred, in 1838, to the Calcografia Camerale, or papal printing house, which in turn would take the name “Regia Calcografia” after 1870, the year Rome was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy. The Views of the National Gallery of Umbria bear, juxtaposedly, the embossed stamp of the Regia Calcografia, but it has not yet been possible to trace the exact date of printing: one can at most fix the terminus a quo to the first year of activity of the Regia Calcografia, and the terminus ad quem to 1917, the year to which the purchase of Piranesi’s engravings most likely goes back, on the basis of an accounting document authorized by the then superintendent Dante Viviani, discovered precisely during the restoration for the exhibition, conducted by Marta Silvia Filippini.

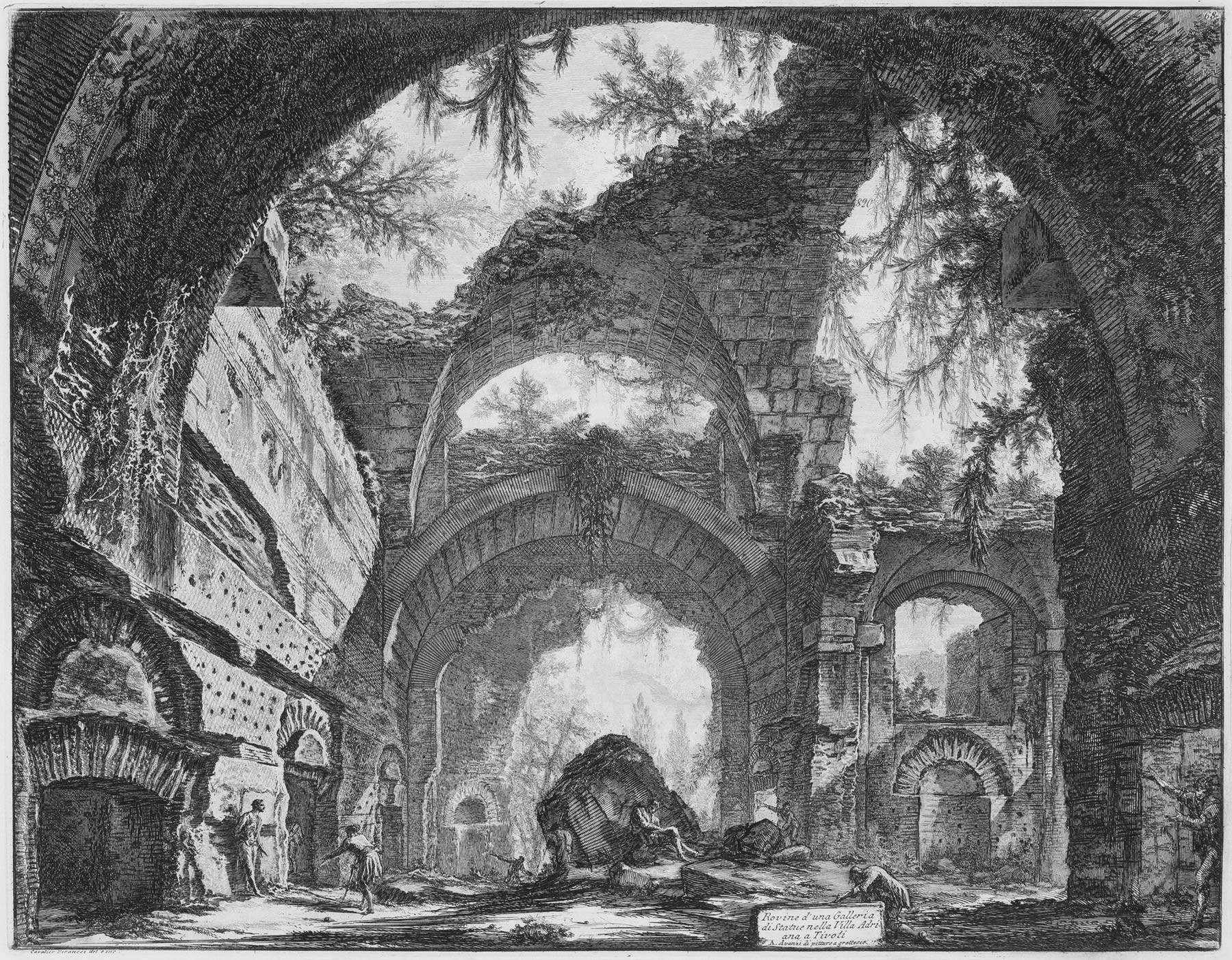

The exhibition offers visitors to the National Gallery of Umbria a comprehensive sampling of Piranesi’s Rome. A Rome where nostalgia for the greatness of ancient times coexists with a sense of an unstoppable modernity alive in the guise of the palaces and villas that take to encompass the vestiges of the city that once was, a Rome where among the ruins of sacred buildings, baths, and centers of power wanders a humanity assorted and busy, among shady and wretched individuals thinking about how to get safely to the end of the day and aristocrats strolling just off a luxurious carriage, a Rome where shepherds, fishermen, laborers, thieves, layabouts, laundresses, lords, ladies, priests, charlatans, travelers move and mingle. An indolent and bewitching Rome, whore and vestal, magnificent in its decline, magnified beyond measure by its storyteller’s sense of the sublime, anticipating Romanticism and offering a grand and terrible image of the city, so much so that Goethe, on contact with the real Rome during his trip to Italy, would be disappointed: “the ruins of the baths of Antoninus and Caracalla, reproduced by Piranesi with quite fantastic effects,” reads a passage from his Italienische Reise quoted in the exhibition catalog, “could not satisfy us at all, up close, the eye addicted to those reproductions.” Piranesi will then be an unfaithful lover in regard to the image of his beloved (what lover is not?), but of that “so beautiful unfaithfulness” that he liked it “infinitely,” as Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi, who already at the beginning of the nineteenth century had posed the problem of whether Piranesi’s “warmth” corresponded to the truth, would have recognized.

Arrangements of

Arrangements of

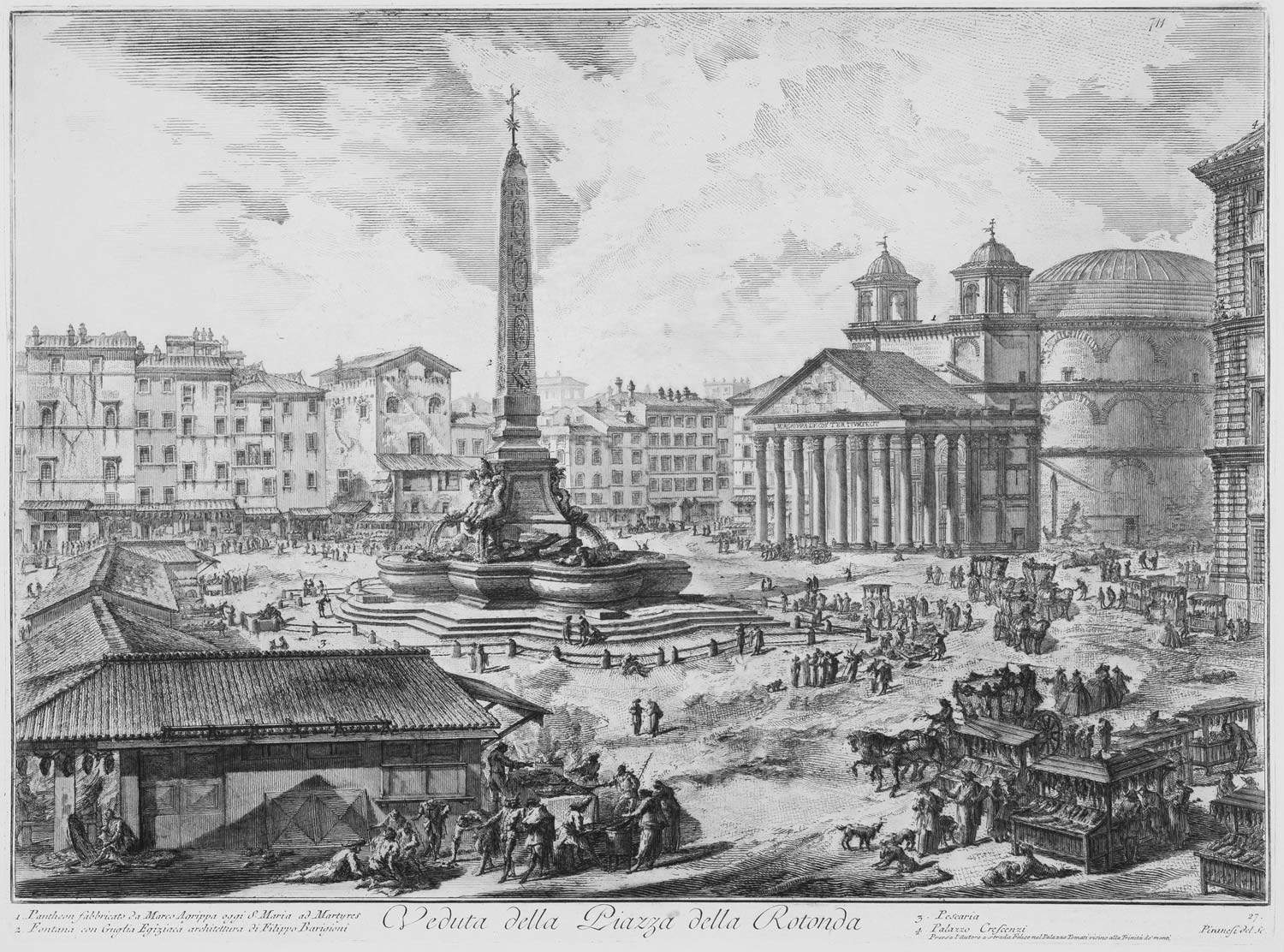

Mario Praz, speaking of Piranesi’s Views of Rome, has written that in the Venetian artist’s images one glimpses “a dramatic elegy of the ancient city, and at the same time the first waking of the modern city; because from the colossal ruins purulent as human corpses will be born in the future the inhuman skyscrapers, the geometric behemoths of modern cities,” and that Piranesi is “the first to give the idea of a metropolis made more to the measure of titans than to the measure of man.” So much so that the selection made by Carla Scagliosi opens not with images of ancient ruins, but with those of modern Rome: after the introductory room, where we are greeted by the frontispiece and the video installation by Grégoire Dupond with music by Teho Teardo (see below), the engravings that open the exhibition give an account of a very lively city. We admire the Trevi Fountain still under construction (begun in 1732, it would not be inaugurated until thirty years later: in Piranesi’s view, much of the statues are missing), we stroll through Piazza Navona captured from all perspectives, we reach Piazza di Spagna, which at the time was not so different from what it is today, we enter a Piazza della Rotonda where the macuteo obelisk takes on much larger proportions than it really does (typical of Piranesi’s views) and where the Pantheon is still flanked by Bernini’s two “donkey ears” that would be torn down only at the end of the 19th century, we move into a Piazza del Popolo crowded with elegant carriages that proceed, however, in the mud, since the streets and squares are not paved, and thus offer, with icastic immediacy, part of the deepest soul of the Rome of the time.

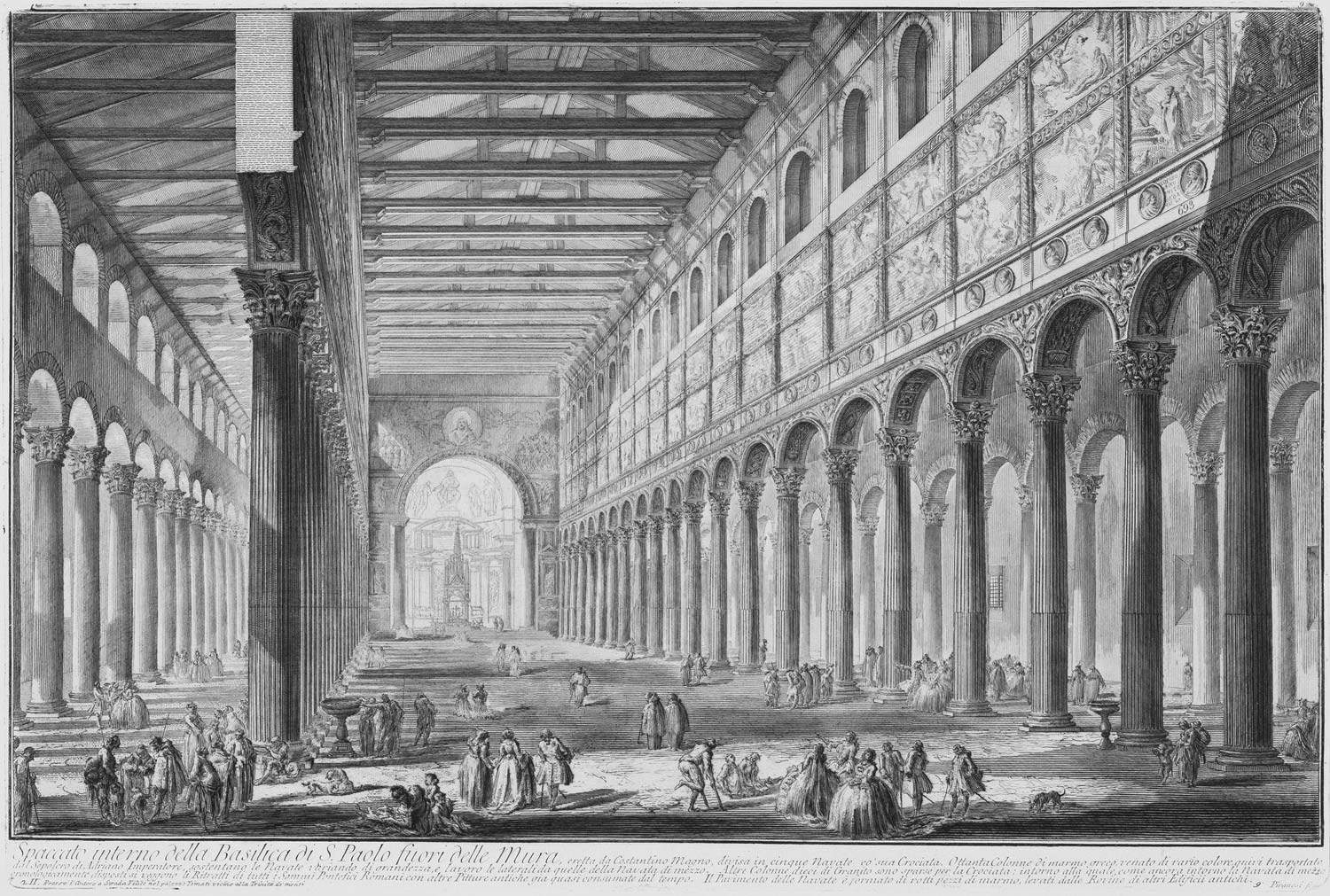

Not far away, Carla Scagliosi offers the visitor some views of Roman churches: St. Peter’s basilica stands out, with Bernini’s colonnade also amplified far beyond its real proportions, not to mention the façade of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, so exaggeratedly cyclopean as to inspire even a certain awe. It is the sense of immensity, of grandeur, Piranesi’s magniloquence of expression that invests every corner of ancient and modern Rome and allows engravings so dramatic as to shake the viewer powerfully: a sense that in the view of St. Paul Outside the Walls, moreover, is heightened even by the violent chiaroscuro that casts the entire side of the church in shadow and with a blade of light brings out the ancient facade, which would later be destroyed during the fire of 1823. Piranesi’s greatness also lies, moreover, in his way of constructing, exalting, and breaking up forms through the effects of light (and see then the skies, the virtuosity of their pictorial effects rendered with the medium of engraving, the fineness of the most minute details for which the view of the Tiber Island alone may suffice as an example): this especially in the more mature Vedute, and for that matter it should be remembered that the collection is the result of thirty years of work on the part of the artist, with all the evolutions, modifications, and changes of idea that an artist can arrive at in such a long period of time. In any case, the curator explains, "it was a matter of bending the tools and methodologies of traditional representation in a scenographic sense by means of such expedients as the amplification of volumes, aerial perspective, wide-angle views, the artificial, iconic isolation of monuments or buildings, the use of different vanishing points, often outside the ’window’ of the depiction, the adoption of the low vantage point or unprecedented cuts, for the purpose of dilating proportions and magniloquent rendering of the image."

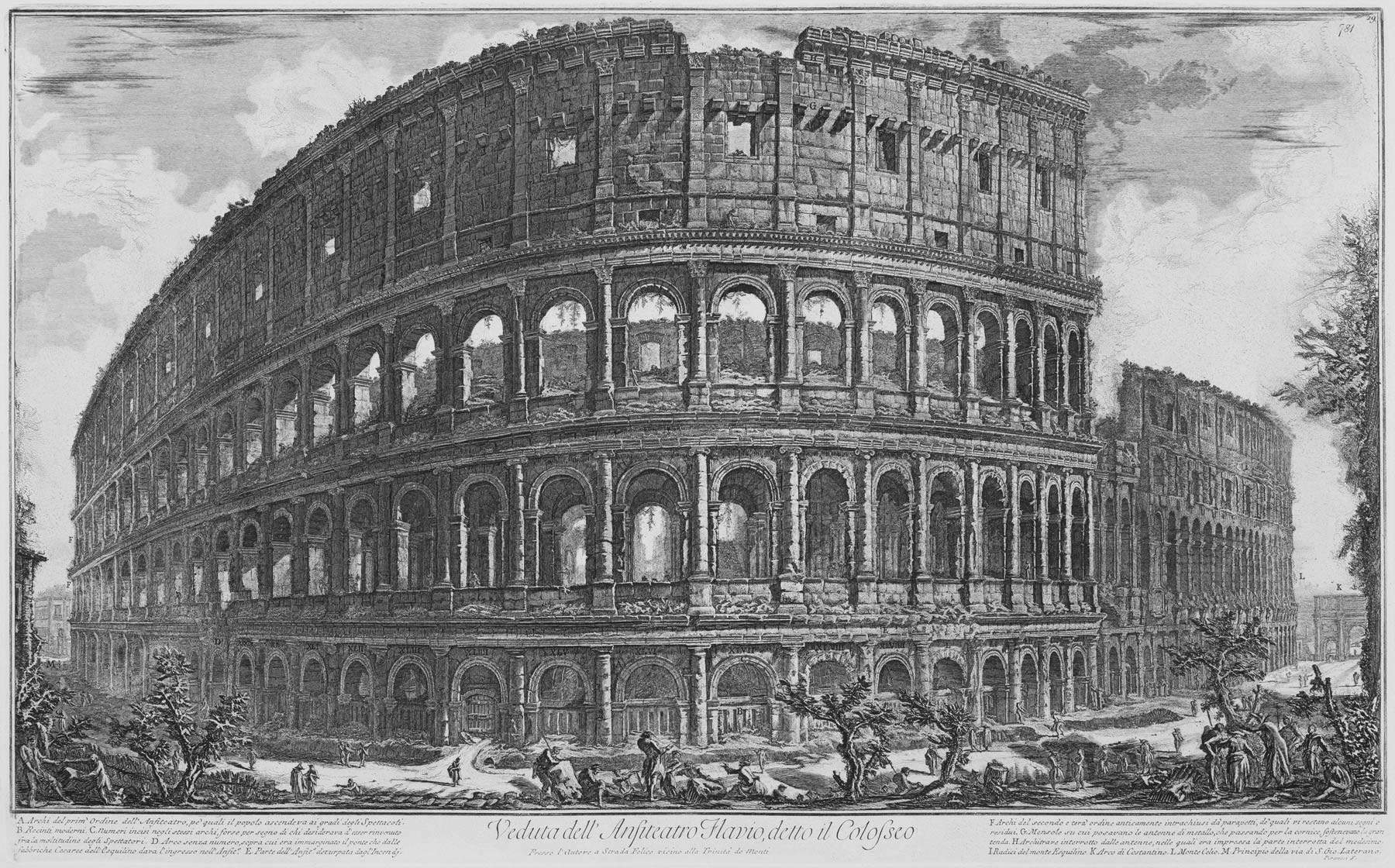

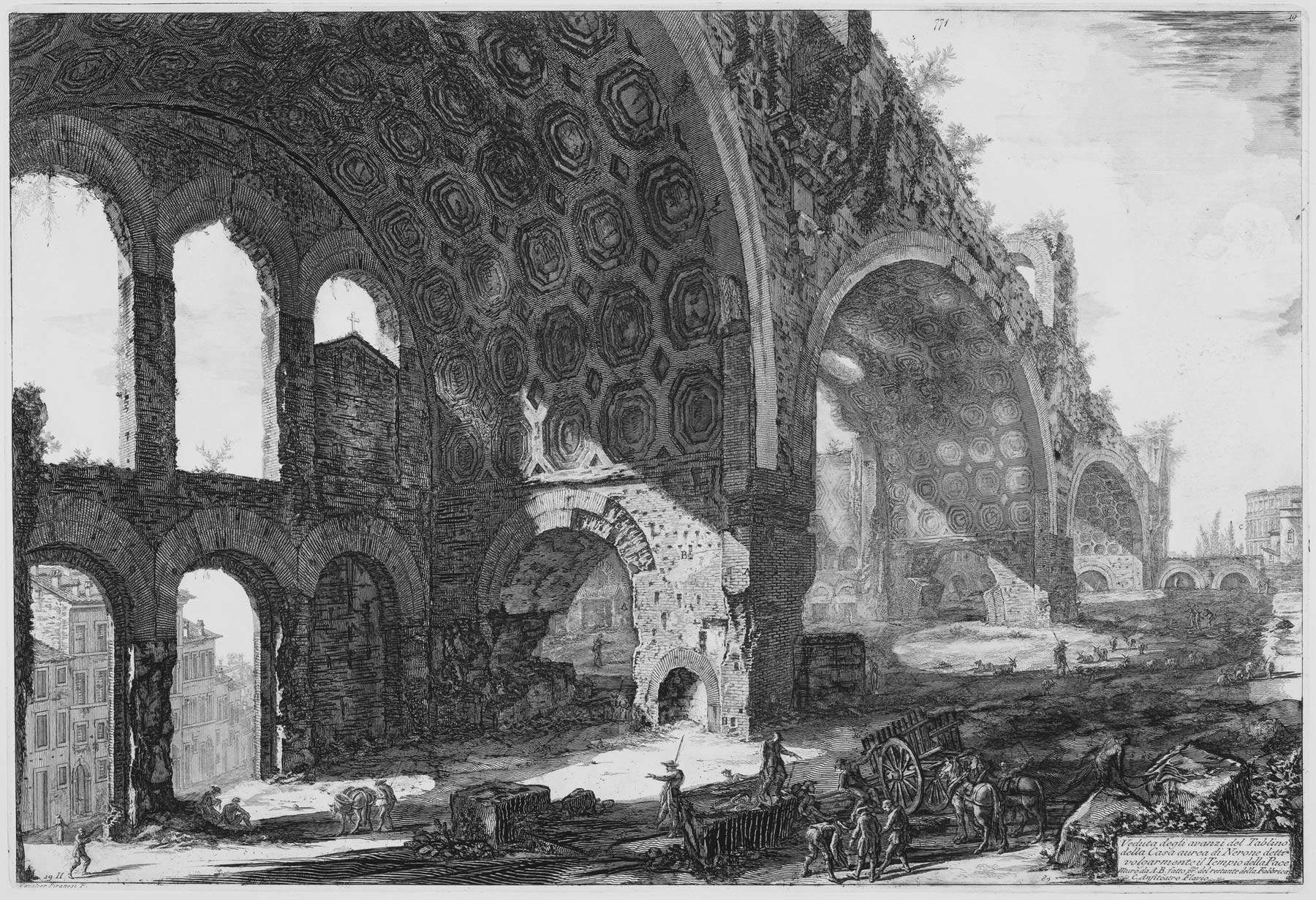

The second room is the one devoted to ancient Rome: here then is the view of the Colosseum, with the succession of arches that becomes almost infinite and with glimpses that for the time were anything but taken for granted (we refer, in particular, to the view from afar on the most ruined part of the Flavian amphitheater, to include even the arch of Constantine), and then the basilica of Maxentius captured with one of the fiercest backlights in all of Piranesi’s production, the Antonine Baths and those of Caracalla, with their ruins that in person disappointed Goethe because they did not give him the same sensations he had felt looking at them on the plates. The ruins of the ancient buildings, devoured by spontaneous vegetation, are perhaps those that most and best entered the collective imagination, capable, moreover, of sounding in unison with the spirit of a Venetian who, before arriving in Rome, had heard their echoes through the architecture of Palladio and Sammicheli: they helped propel generations of grand tourists to Italy, they forged the myth of a triumphant, powerful, voracious, imperious, eccentric Rome, so different from the Greece of the strictly observant neoclassicists, and more than any other Piranesian view they deliver to us the image of time that overwhelms all, that swallows up glories and riches leaving rubble behind, and they convey to us a sense of the ruins that anticipates Georg Simmel, inert and eloquent remnants of the struggle that pits the will of the spirit against the necessity of nature, tragic witnesses of a dead civilization, a portent of what will be.

Valuable operation, then, that of the National Gallery of Umbria, which retrieves from its deposits an exhaustive selection of Piranesi’s Views of Rome and offers its public the not so frequent opportunity to see, all together, a well-representative nucleus of the collection. And worthy of all praise is the curator’s decision to exhibit all the engravings without the interposition of glass, so that the visitor is truly offered the uncommon opportunity to appreciate up close, lingering on the details and observing it without filters, all the technical skill with which Piranesi engraved the matrices to arrive at those results of such extraordinary precision that surprise one every time one has the pleasure of admiring his sheets. “Despite the limitation of the monochrome of etching,” Scagliosi writes, “Piranesi’s palette is rich in innumerable shades of blacks, from the most opaque to the most glossy, and a vast gradation of grays, obtained through the repeated morsures and the different depths of the grooves created by baths in acid or etching. Piranesi demonstrates a profound knowledge of engraving techniques, which he experiments with and bends to his liking to best render the pictorialism that distinguishes his works.” Of course, Marta Silvia Filippini’s restoration contributed substantially to the final result: the sheets, as a result of the action of time, old restorations and damage suffered, showed folds, oxidation, browning, stains, and halos that Filippini remedied with an initial, thorough cleaning, which was followed by the cleaning of the surfaces, the recovery of lacerations and the repair of gaps, ending with the arrangement of the sheets in cardboard passepartouts that were much more suitable for conservation than the folders in which the panels were previously contained. And finally, a detailed photographic campaign was carried out that led to the high-definition filming of all the plates.

It was mentioned above that entry to the exhibition is accompanied by the viewing of a video installation, which screens the animated film Piranesi, Prisons of Invention by Grégoire Dupond with a soundtrack by Teho Teardo(The Ghost of Piranesi: the 45 rpm, a splendid idea, is included in the catalog): the French artist has made a short film that gives way to enter Piranesi’s prisons, to allow the viewer to make a kind of three-dimensional investigation inside Piranesi’s mind with the medium of his most disturbing work, which is experienced firsthand thanks also to Teardo’s music that tries to convey the sense of mystery, anxiety, and disturbance that one feels when observing the Carceri d’invenzione. It is a high-level synaesthetic experience that gives one a way to totally immerse oneself in Piranesi’s universe. The result is, on the whole, an exhibition that is indeed small in size but supremely refined, a work of great quality on the deposits that leaves high expectations for the next “installments”: after the Vedute di Roma it will in fact be the turn of the Antichità d’Albano to pass through the restoration laboratories. What’s more, the work done on the new arrangements, resulting in the reorganization of the Gallery’s Library, has led to an extensive reconsideration of the institute’s entire holdings, including its bibliographic holdings, and the exhibition on Piranesi’s Vedute is the first fruit of this. It looks forward to the continuation.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.