To walk through any major city today is to move through an open-air museum, but not always of paintings or sculptures. The windows of fast fashion brands display images, shapes, and colors that seem stolen from anart history catalog: Van Gogh prints on cheap clothes, Warhol quotes on mass-produced sweatshirts, geometries reminiscent of Mondrian transformed into fluorescent leggings. This is not a new phenomenon, but never before has it seemed as invasive, almost inevitable. What kind of relationship has been created between art and fast fashion? Is it a democratization of beauty or theft disguised as homage?

Fast fashion lives off what art has always produced: powerful images, recognizable symbols, colors that speak directly to the eye. But the logic that governs these two worlds is radically different. Art needs time: time to be created, time to be understood, time to settle. Fast fashion, on the other hand, feeds on speed: the weekly cycle of collections, the rush to the new, the anxiety not to fall behind. When the two universes meet, inevitably something breaks. The work of art, which is born unique and unrepeatable, is reproduced on millions of T-shirts; the painting, which claims contemplation, becomes a pattern to be consumed and discarded. Yet, it is precisely this fracture that makes it fascinating: the promise of wearing a museum piece, if only for an evening.

Can we really talk about homage? Or are we dealing with outright misappropriation? When a low-cost brand prints a detail from Van Gogh’s Starry Night on a bag, without mentioning the context, is it making art more accessible or is it emptying it of its meaning? Is it democratization or trivialization? The line is a fine one. On the one hand, millions of people who may never set foot in a museum can come into contact with an artistic language. On the other, the message that comes through is distorted: art reduced to a decorative surface, an interchangeable pattern, deprived of its critical force. But there is another contradiction burning beneath the surface. Much of fast fashion comes from opaque supply chains based on exploitative labor and devastating environmental impact. So what does it mean to print the face of Frida Kahlo, a symbol of freedom, of resistance, of female identity, on a T-shirt sewn by an underpaid worker in Bangladesh?

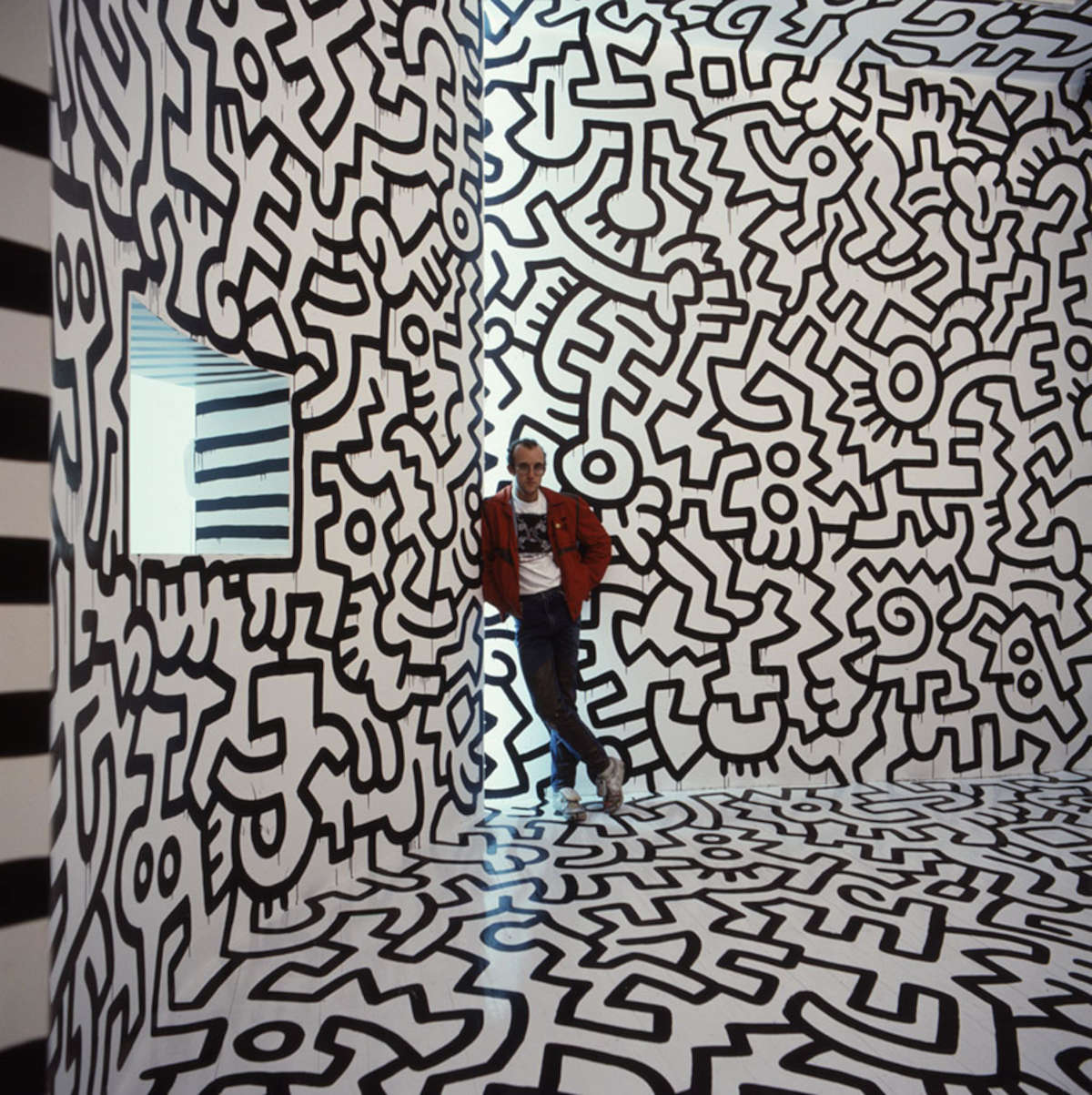

The scandal here is not aesthetic, but ethical. Art, which has often embodied the voice of the fragile, is being turned into a brand for a system that perpetuates inequality. And it is not enough to call it “inspiration” to erase this contradiction. It must be said, however, that art does not always suffer passively. In recent decades, many artists have decided to engage in dialogue with the fashion system, even the most rapid and commercial one. Keith Haring, already in the 1980s, understood the power of reproduction and turned it into language, opening a Pop Shop selling gadgets with his iconic figures. Jeff Koons collaborated with Louis Vuitton, Takashi Murakami transformed the fashion house into an explosion of manga and colorful flowers.

This is no longer appropriation, but contamination: the artist uses fashion to spread his own imagery, while the brand is clothed in a cultural aura. But beware: this is about luxury, not fast fashion. When the price of a bag is inaccessible to most, art does not democratize, it elititarizes even more.

Perhaps, then, fast fashion steals no more from art than it does from any other language of our time. It appropriates, digests, gives back in quick and superficial form what elsewhere requires depth. That is its nature: to live by acceleration, by consumption, by oblivion. But this is where the real question opens up: is it not precisely this that scandalizes us, even more than aesthetic trivialization? Not so much that Warhol ends up on a T-shirt, but that that T-shirt is destined to last three washes before ending up in the landfill. It is not art that is violated, but our relationship with time and things. In the end what remains is an unresolved tension: art tries to resist as a space of thought, of the slow, of the unique, fast fashion instead drags it into the universe of the quick, of the disposable, of the multipliable. Is it an unequal struggle? Perhaps. But it is also the perfect snapshot of our age: an age in which everything can be copied, consumed, forgotten. The question, then, is not whether art should defend itself against fast fashion, but whether we, as an audience, are able to distinguish between pattern and work, between icon and cliché, between consumption and contemplation.

The relationship between art and fast fashion is not meant to end in a final judgment. It is a terrain of conflict, of ambiguity, of constant contamination. There are times when fashion seems to betray art, and others when art uses fashion to make itself stronger. Often art is in danger of becoming a consumable surface, everywhere and in every form; other times, however, it claims a space of sacredness, slowness, and uniqueness. After all, the next time we wear a T-shirt with a famous painting on it, we should ask ourselves: are we carrying a piece of beauty with us or contributing to emptying it?

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.