What does it mean to talk about art as the world collapses, as the chronicle is reduced to an inventory of bodies? The question returns compulsively every time the world seems to be crumbling, every time the images of the present pile up like ruins and numbers replace faces, every time the word “dead” loses weight by the mere fact that it repeats itself relentlessly. We become accustomed, without meaning to, to the daily count, to headlines that last one day and are swallowed up by the next, to photographs that no longer hurt because they blur into one another. It is in this mechanism that too often social media, and with them certain journalism, slip into the rhetoric of emotion on command, in which every tragedy becomes material to be relaunched, packaged, and monetized. It is no longer testimony, but a strategy to remain visible, to gather likes, clicks, views. Suffering is slammed on the front page or in feeds as a commodity to be exhibited, consumed until it is emptied of meaning, reduced to a passing spectacle, a fetish to be shrugged off and forgotten. And so the temptation is certainly to think that talking about art in the midst of all this is out of place, an unnecessary luxury, a gesture one cannot afford. But it is not. Talking about art today, as yesterday, does not mean looking away from the catastrophe: it means preventing the catastrophe from erasing everything. Because when violence strikes it doesn’t just destroy bodies, it razes archives, libraries, museums, theaters, churches and all those structures that hold a collective memory. For to strike a people is to strike its images, its words, its traces as well. This is the logic of total war, which wants to annihilate not only life but also any possibility of remembering it.

During World War II, Warsaw’s libraries were systematically burned, in a cold, planned operation to erase every trace of a people’s written memory. The Nazis purloined thousands of masterpieces from European museums, amassing them in storage or destined for the Reich’s private collections. Bombed Italian cities lost churches, frescoes, and archives: the mosaics of Ravenna were protected by improvised masonry, statues covered with sandbags, medieval altars disassembled and hidden underground to save them from the blind fury of the bombs.

Yet in the midst of that devastation there were those who did not stop resisting with images. Pasquale Rotondi hid at the risk of his life thousands of works in the Marche region, including Titian, Giorgione, Piero della Francesca, Rubens, Bellini, and Raphael. He lived in a freezing palace, with crates crammed into rooms that became secret shelters, while outside Italy was torn apart by occupation and bombing. But it was not a solitary gesture, for many superintendents and officials traveled with anonymous crates, escorting them at night on unmarked trucks, passing through checkpoints, pretending to move or transport common objects to save fragments of a heritage that would otherwise have been dispersed. Every hidden painting, every statue rescued from looting was a political act, a way of saying that culture would not be wiped out along with bodies.

And then there were the invisible gestures, seemingly minimal, revealing their full significance only years later. Primo Levi, in the horror of the lager, repeated Dante to himself from memory. A fragment recited to himself or shared with a fellow prisoner was enough to remain anchored in something that could not be confiscated. These were not verses recounted for pleasure, but words that held life. The song of Comedy became resistance, a very thin thread that separated him from the abyss of annihilation.

And so saving a painting, hiding a book, remembering a verse meant opposing the project of total erasure. It meant saying that a people is not reduced to the bodies that make it up, but also to the images, texts and memories that run through it. It meant claiming, in the midst of destruction, that art is not superfluous, but one of the few things that prevent nothingness from winning. And it still is. Today, when conflicts return to devastate cities and villages, art continues to resurface not only as an individual gesture, but as a collective practice that endures within the rubble. In Kyiv, as Fabio Cavallucci recounts in this report in Finestre Sull’Arte, museums have not closed, many galleries continue to open exhibitions while sirens are ringing outside, artists are working inside war-wounded spaces. And this is not an act of levity or insensitivity, but proof that art, even when cornered, rediscovers its civic and political reason: to hold a community together, to prevent destruction from erasing even the imagination of a people. It is the exact same stubbornness that animated those who hid a Titian in a wooden crate or recited Dante behind barbed wire. Only today we are not facing a memory of the past, but a present that demands to be looked at. Kyiv is not an exception but an example of how art can continue to be necessary despite, and perhaps because of, catastrophe.

But while this is true, it is equally true that not all art is capable of withstanding this test. There is art that weighs, that leaves bruises, that does not console, and there is art that, on the contrary, tames pain, translates it to simulacrum and, in the end, renders it trivially harmless. This is the distinction we must make today if we want to continue talking about art without making it complicit in the noise that surrounds it.

I think of director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Carne y Arena, the immersive installation that had you wearing a visor, walking on the sand, feeling the water rising around you as you experience the escape of a migrant. It was celebrated as a powerful, necessary experience, capable of restoring empathy. And in fact what strikes me is not the absence of pain, but its reduction to a reversible experience: a simulated trauma, calibrated for the Western viewer who knows he can take off the visor and immediately return intact to his own life. In this way, the work ends up turning suffering into spectacle, in a sensory exercise that does not restore the depth of the wound but neutralizes it, offering only the illusion of understanding.

Here I am reminded of Paolo D’Angelo’s pages in the essay The Tyranny of the Emotionsin which he shows how our time has elected emotion as proof of truth, to the point of believing that sensory impact is equivalent to real experience. But it does not. A thrill, a tear, an immediate jolt are no guarantee of authenticity, but only the product of a device that constructs the effect, that orients the response. D’Angelo speaks of the risk of substituting emulation for catharsis, of confusing immersing oneself in a simulacrum with having really understood what it represents. It is a mechanism that gratifies the viewer, offering him the feeling of having “felt” something, but without delivering him to the truth of the trauma.

Carne y Arena sits exactly in this ambiguous space: instead of opening a wound, it tames it; instead of forcing one to come to terms with suffering, it returns it in the form of emotion ready for consumption. It is the same dynamic that D’Angelo describes as “tyranny”: when art abdicates complexity to rely on the calculation of emotional impact, when it measures its value by the immediate emotion it can produce. It is no accident that the viewer may leave the installation convinced that he has experienced a piece of truth, when in fact he has only experienced the security of reversibility.

Perhaps Abbot Dubos, in his Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture of 1719, would have seen merit in all this: art that moves without shedding blood, theater that allows you to weep without really experiencing tragedy. But today, in this world that has changed inexorably, that distance is no longer catharsis; it is simply alibi. It does not deliver us to the truth of trauma, but protects us from it. It offers us a calibrated thrill, a superficial shock that leaves no scars.

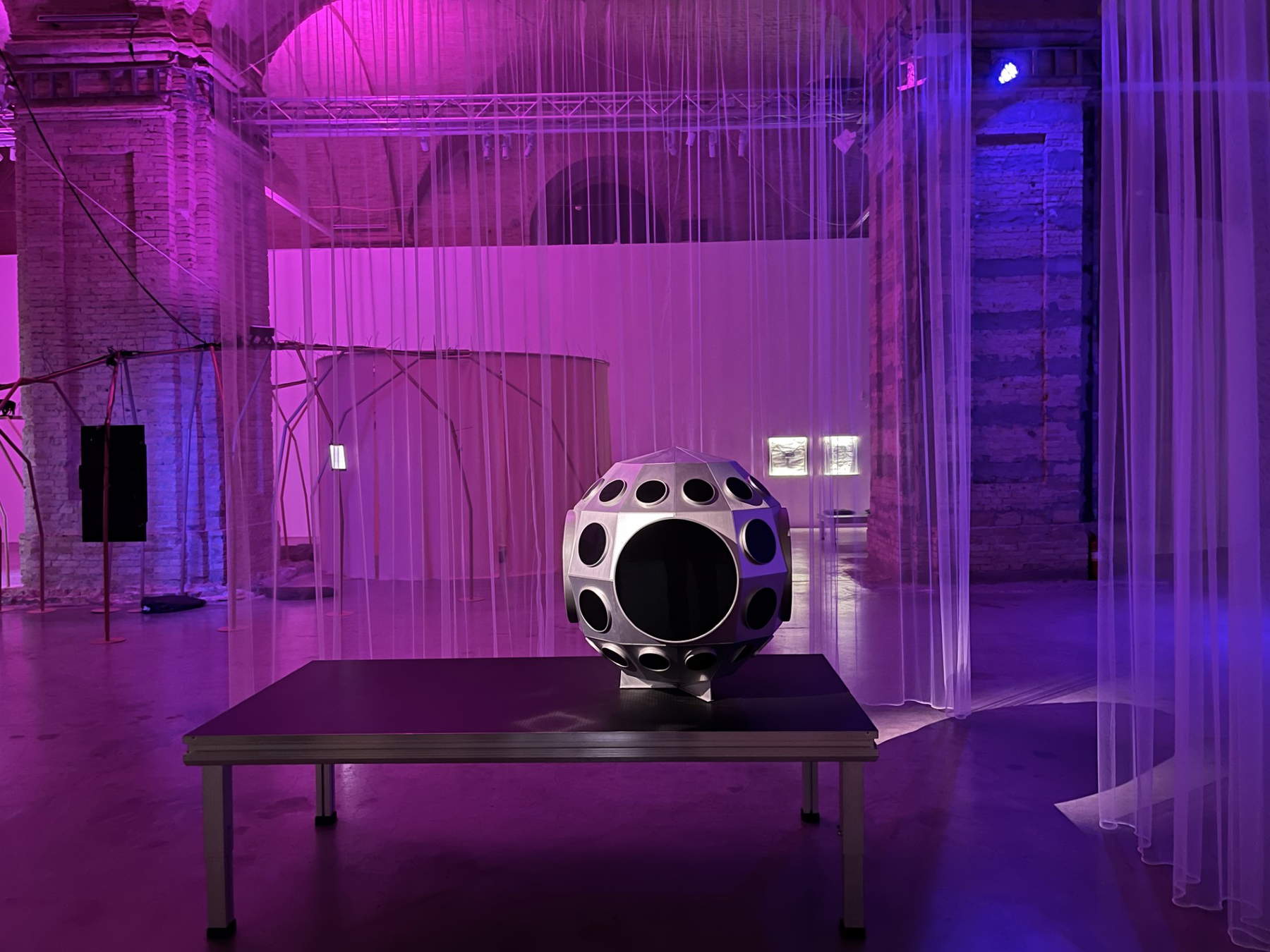

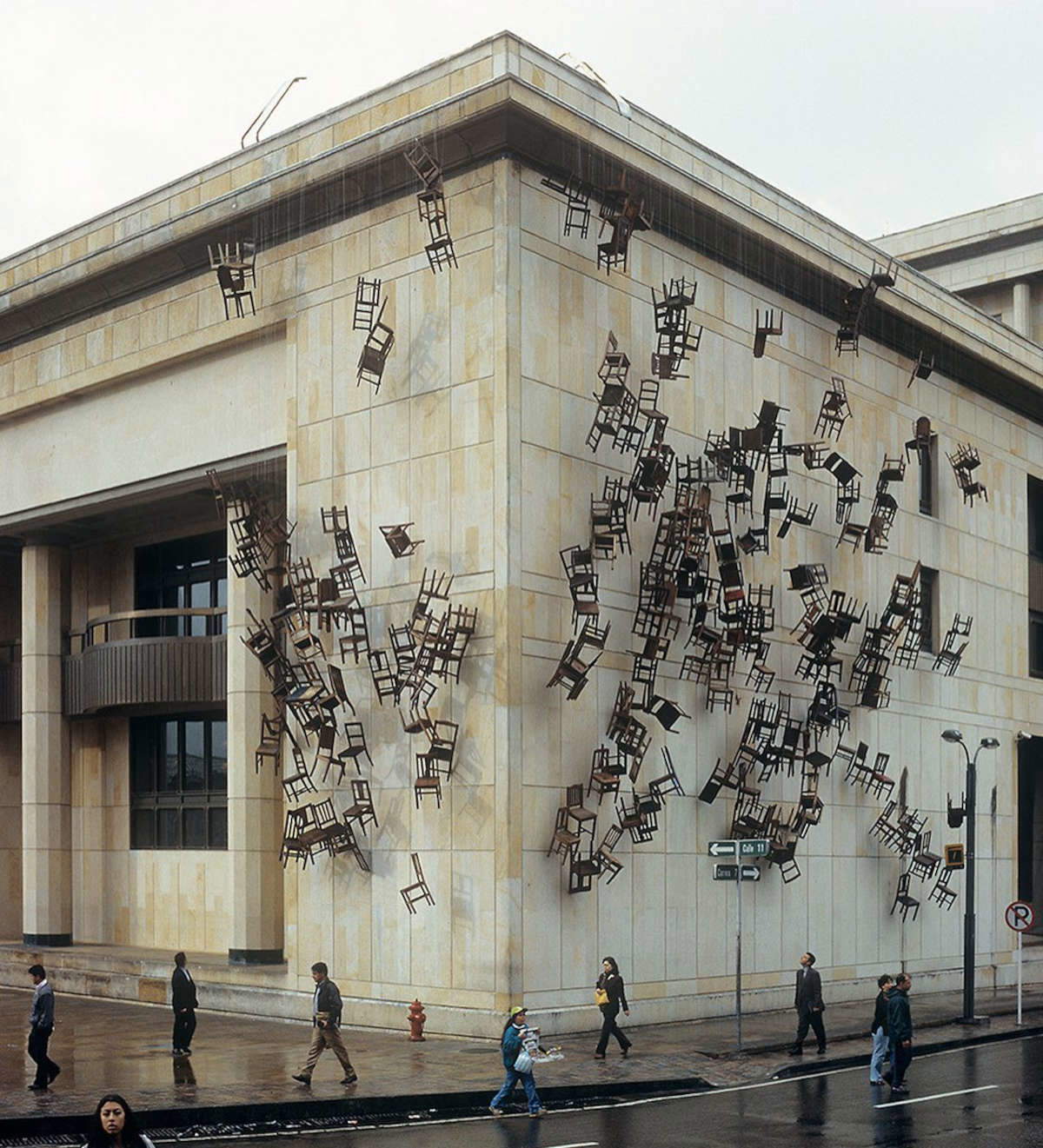

Yet there are works that do not try to domesticate trauma but turn it into habitable space, make it matter that weighs, that resists any aestheticization. This is what happens in front of Noviembre 6 y 7, Doris Salcedo ’s intervention in Bogotá, when in 2002 she transformed the facade of the Palacio de Justicia into an ephemeral monument to memory. Thousands of communal chairs leaned against the surface of the building, evoking the absent bodies of the 1985 massacre, when the assault by the M-19 guerrilla group and the subsequent army offensive reduced the building to ashes and with it more than a hundred lives, including those of eleven judges. This work was a silent flow of absences that affected the eyes and bodies of those who passed by. But still I think of those who chose not to show the horror, subtracting images to return their own impossibility. This is the case of Alfredo Jaar, an artist who grew up under the Pinochet regime and has always been committed to denouncing the indifference with which the world looks at contemporary tragedies: from the genocide in Rwanda to the migrations between Mexico and the United States, to the coup in Chile. For him, art is “the last corner of freedom,” an act of resistance that holds ethics and aesthetics together, never separating the form from the wound within. In Lament of the Images, for example, Jaar staged darkness interrupted by blinding light, a screen dazzling the viewer or two overlapping light tables emanating absolute white. Here, photography does not show, but portrays itself; the incessant flow of images around us is slowed down to silence or sped up to annihilation, leaving us with only the perception of emptiness. It is a radical reflection on the power of images and their ineffectiveness in the face of visual excess that anesthetizes the gaze. To watch Lament of the Images is to be forced to close one’s eyes not to escape the horror, but because there is nothing to look at: a whiteness that lacerates, that forces one to come to terms with the very limit of representation. It is the revelation that sometimes visual silence is the only way to restore the depth of a wound.

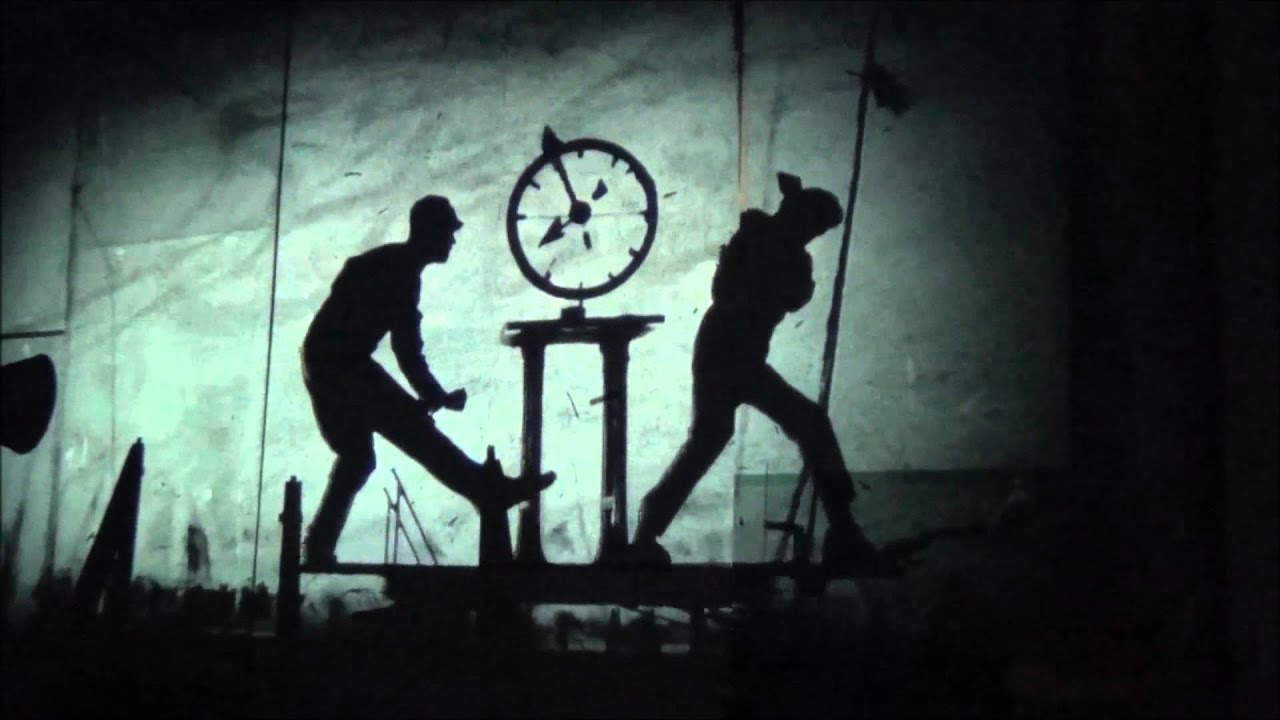

Another form of resistance comes through the unstable shadows of William Kentridge, who told the story of post-apartheid South Africa through black, flickering figures projected on walls and screens. They seem on the verge of dissolving, swaying like spectres, leaving one wondering whether what one is looking at belongs to the past or continues to exist in the present.

But as I write I realize that perhaps the point is not to determine whether it makes sense to talk about art as the world collapses, but to ask what art becomes in that collapse. Not as a consolation that lightens, not as a compulsive exhibition that turns suffering into consumption, but as a practice of survival, as an act that exists because it is inherent in being human. War destroys bodies and homes, but it does not erase the need to leave a mark, to tell one’s story, to entrust at least a fragment of oneself to the future. In Syria, during the fiercest years of the civil war, the walls of Aleppo were filled with improvised graffiti: faces, phrases, quick strokes, knowing they would be erased almost immediately. It was affirmation of existence: saying “we are here,” even though we would no longer be here the next day. But still, in Afghanistan, beginning with the Soviet invasion, the centuries-old tradition of carpets cracked and changed its skin. Between floral patterns and ancient geometries appeared helicopters, Kalashnikovs, tanks: the chronicle of violence woven into the wool, a daily archive recording the trauma. One carpet shows a red dome surrounded by military vehicles: it is symbolic of how war penetrates the very fabric of life, but also of the ability to transform horror into visual language, to bend a traditional code to tell what cannot be unspoken.

And then there are the less visible but no less radical gestures, those that do not pass as art objects in the strict sense. In 2012, when jihadists were devastating the libraries of Timbuktu, burning archives and collections, a group of librarians and ordinary citizens hid thousands of ancient manuscripts in metal crates and sacks of rice. They carried them away in clandestine caravans down the Niger River, risking their lives to secure texts of theology, science, poetry, copied by hand over the centuries. They were material evidence that a community had written its own history, that it had produced knowledge and culture.

Art, understood in the broadest sense, survives even where there are no museums or catalogs, even where no one would call it by that name. It is not born out of privilege, but out of the urgency to tell one’s story, to recognize oneself as human, to leave a trace when everything seems destined to disappear. It is no accident, then, that art continues to resurface even in the rubble. The point is not just to note its existence, but to ask how we tell about it. For if art does not disappear even under bombs, it may instead disappear in the way we reduce it to spectacle, to quick consumption, to pornography of suffering. Talking about art today means taking the responsibility to distinguish, to say that not everything has the same weight, that not every work deserves the same attention, and that there is a clear difference between those who aestheticize pain and those who go through it without domesticating it.

That is why continuing to write about it is not escapism, but commitment. It is taking a stand, choosing words to prevent violence from writing history on its own. It does not mean claiming to save the world with an article or an exhibition, but recognizing that even our gaze contributes to determining what will remain and what will be forgotten. Art, after all, always endures; the real question is about us: whether we will be able to tell the story without betraying it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.