It took Tomaso Montanari and Pablo Echaurren to unravel the usual skein of lavish, unconditional but mostly prone and clueless praise that accompanied yet another arrival in Italy of an artist who enjoys minimal international fame: and, as far as the Italian press is concerned, if you have the good fortune to be an artist, to boast considerable wealth, to benefit from a fame that has now reached every corner of the globe, and to even call yourself Jeff Koons, as well as to awaken some itches in the most âgé art lovers, because your resume includes a year of marriage to Cicciolina resulting in a series of hyper-realist porno-trash paintings, then you must necessarily have something to say. Patience if then the art critics from fourth-rate magazines (but also those who write on many of the most illustrious national newspapers) and social network commentators (the latter immediately ready to storm images of Koons’s works with likes ), despite their laborious searches, cannot find anything serious to say about you and are forced to cover with high-sounding adjectives the pneumatic vacuum on which you, the king of planetary kitsch, from overseas, have built your art and founded your fortunes: here, then, is the genesis of all that abundance of “gestaltic,” “transeunte,” “pellicular,” as well as assorted locutions that seem to have arisen from the combination of nouns and adjectives joined together by randomly leafing through a dictionary, with the unstated goal of conferring some sort of verbal legitimacy on nothing.

|

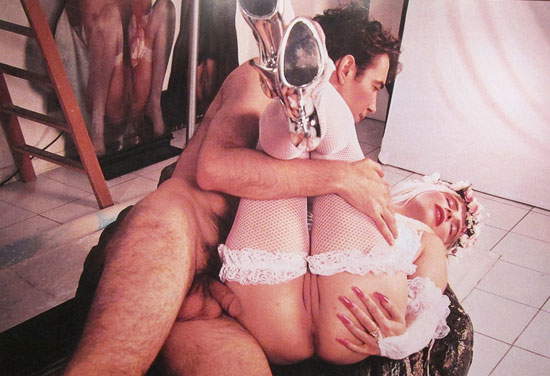

| Jeff Koons, one of the works in the Made in Heaven series (1989-1991) that depicts him with his wife Cicciolina |

Jeff Koons is considered by many to be a kind of successor to Andy Warhol. However, perhaps the dimension that suits him best is that of theepigone who takes up the master’s ideas in a tired and superficial way.Jeff Koons, for example, totally lacks Andy Warhol’s cynical and disenchanted eye. Andy Warhol used his own irony to criticize the system. Jeff Koons is the system, and one only has to take a look at the photographs of the harlequinade parade that greeted his arrival in Florence, complete with majorettes in blue wigs and gozzoviglie in the Salone dei Cinquecento, to realize how much the American artist is cast in this system that is based, to use Echaurren’s words, on the “subservience of the media and administrations” (our own, but often foreign as well), on the “self-satisfaction of the exhibition of value understood as price,” and on the “inadequacy complex” that investors, from the Impressionists onward, have always felt toward artists, and has thus led them to tailor-made art, to be exploited at will, whose success they decree a priori. But it is not necessarily the case that the market always produces art pregnant with values.

And, as mentioned, Jeff Koons’s art is based on the vacuous and the ephemeral. And this is not a novel opinion from yours truly; I have been preceded by far more distinguished pens. “Imagine the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art as a perfect storm. And, at the center of the perfect storm is the perfect void. The storm is everything that revolves around Jeff Koons: the multimillion-dollar auction prices, the blue chip investors, the hyperbolic assertions of the critics, the adulation but also the quarrels of the public who, as is only natural, want to know what all the hype around the artist’s work is about. Emptiness is Jeff Koons’s art, a continuous succession of pop-culture tropes so soulless that even the most hardened museum-goers look a little confused as they pull out their serviceable iPhones and snap their selfies”: so wrote Jed Perl in The New York Reviews of Book just a year ago. A multimillion-dollar void, in short, that has placed the tombstone on all the good intentions of conceptual artists who have had something to affirm since Duchamp: if the point ofDada art, and its derivatives, was to deny art as mere aesthetic complacency, albeit in a radical way, as well as to make the ready-made stand as a symbol of the fact that art is not untethered from reality, Jeff Koons, with his work exhibited in Piazza della Signoria, completely overturns the Dada message. The Koonsian ready-made is nothing more than a small porcelain work from 18th-century France, vaguely inspired not by Gian Lorenzo Bern ini’s Rape of Persephone (nor, much less, is Koons inspired by Bernini’s work, as many who have not bothered to delve into the work have written), but, more likely, by some sculptural group made by one of countless European Baroque artists. Jeff Koons did no more than obtain a three-dimensional scan of the small piece of art: he then enlarged it, reproduced it in steel and gilded it. As a result, the less shrewd (but perhaps also the more shrewd) critics praise not the message of the work, which should be the foundational basis ofconceptual art, but the supposed Berninian inspiration, or even the “provocative beauty” (...one would wonder which) that Koons’s works are supposed to arouse in those who admire them.

|

| Jeff Koons, Pluto and Proserpine (photo by Francesco Rolla) |

It is, in short, the exact opposite of the goal of Dada art, which should prompt the viewer to ask questions. And, if you will, also of pop art. Jeff Koons is pop not because he criticizes consumer society, but because he is pop himself, in the most banal sense of the term. And probably one of the secrets of his success lies precisely in his being inherently and viscerally pop. Record stores sell Katy Perry albums well and not those of, I don’t know, Federico Fiumani. At the cinema, people line up to see trashy little movies. Even the Impressionists have been turned into a pop phenomenon, with endless lines in front of museum doors to sample the intangible emotions that only the art of Monet and co. would seem, according to marketing, to provide. It is therefore no wonder that Jeff Koons’ art is the critically acclaimed art of our time. “If you don’t like Jeff Koons’s art, take it up with the world,” wrote Peter Schjeldahl of the New Yorker a few months ago. One can hardly blame him. But it is also true that we have every right to have our say, and not to have to submit to every commercial operation that is foisted on us by local governments that are evidently short on ideas, as well as cultural preparation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.