Kicking off the new season of the Wednesday Addams series on Netflix, which has achieved great success with its dark aesthetic and gothic charm: for the occasion, we have selected six places in Lombardy that seem to have come straight out of an episode of the Addams family. Ruined castles, charnel houses decorated with skulls, abandoned villas shrouded in legend and alpine valleys marked by the memory of witches: Lombardy holds a dark and fascinating soul, ready to surprise anyone. From Milan’s Monumental Cemetery, where statues connect with time and death, to the rock carvings of the Camonica Valley, the scene of ancient persecutions, the sites chosen tell a story that combines art, mystery and memory. And if theSan Bernardino ossuary with its skulls arranged in Baroque geometries may remind one of a Gothic movie set, Villa De Vecchi in Cortenova, known as the Red House, seems tailor-made to evoke eerie presences. Here are 6 of the most mysterious places in Lombardy.

Padernello Castle, a 15th-century manor house surrounded by a moat and equipped with a drawbridge that still functions, stands in the rural village of the same name in the province of Brescia. It belonged to the Martinengo family, a branch of the Counts of Padernello, and in the 18th century was transformed into a mansion. Passed to the Salvadegos (who had Venetian origins) in the 19th century, it was then abandoned after 1965. Covered by brambles and a victim of neglect, it was rescued by a group of visionaries gathered in the Padernello Castle Foundation, which began the recovery of the manor and village. Today the castle, known to art lovers because a precious cycle of paintings by Giacomo Ceruti was found here in the 1930s, has been reborn thanks to a public-private partnership. Thanks to the cooperation and support of institutions and foundations, the Ballroom, courtyard, Gentile Chapel, historic kitchens and other rooms were restored between 2006 and 2015, restoring life and cultural functions to the castle.

The legend of the White Lady hovers among its rooms. Biancamaria Martinengo, daughter of Count Gaspare Martinengo, one of the descendants of Antonio I Martinengo, invested in 1443 by the Venetian Republic with the fiefdom of Gabiano (the ancient name of Borgo San Giacomo), and Caterina Colleoni, Biancamaria was a nature-loving young girl. In 1479 she moved from Brescia to her country residence. On the evening of July 20, 1480, at the age of thirteen, enchanted by fireflies, she leaned out from the battlements of the castle and fell. Every ten years, on the night of her death, Biancamaria returns in ethereal form, dressed in white and with a golden book open in her hands, looking for someone who can listen to her.

Milan’s Monumental Cemetery is one of the best known places in the city and at the same time a great open-air museum for the value of its architectural and sculptural works. Born out of the need to replace the old city cemeteries with a single, more salubrious and decorous area, the project took shape in 1860 thanks to a competition announced by the new City Hall. It was won by Italian architect Carlo Maciachini (Induno Olona, 1818 - Varese, 1899). Work began in 1863 and the cemetery was inaugurated in 1866, although not yet completed. In the following decades, the enclosure, Ossuary, Famedio and other extensions were added, until it reached an area of 250,000 square meters. The main building, decorated with fine marble and local stone, develops symmetrically with galleries and arcades, shrines and monuments that fit into an orderly urban layout. The Cemetery is traversed along its entire length by a central avenue that divides it into two symmetrical sections. Along the way are the Ossuary building and the Necropolis, before ending in the Crematorium Temple.

The route through the Cemetery introduces some of the funerary sculptures related to mythology and presents a small taste of its symbolic heritage. The most recurring figure is Chronos, god of time, depicted as a bearded old man: seated on the globe in the Molteni monument, with the hourglass in the Meraldi monument, and with the scythe in the Rancati Sormani monument, where he takes on the guise of death.

Another frequent theme is that of the Moire (or Fates), the three sisters who weave, unwind and sever the thread of life. They appear in the Bazzoni monument and the Toscanini aedicule, where Atropo is recognizable by her scissors. They are often mistakenly attributed with the ability to predict the future through a shared eye, a characteristic instead of the Graie, guardians of the Gorgons. Among them, Medusa is depicted in the Fabe monument, intent on wrestling with a young aviator. In the Pozzani monument, the owl appears, a symbol of philosophy and the goddess Athena, but also an omen of death according to popular tradition. Finally, the Rocca monument shows the soul with wings of a moth, psyché in Greek, symbolic of spirit, soul and the transience of life.

Among the peaks of the central Alps, between the present-day provinces of Bergamo and Brescia, the Valle Camonica, or Camonica Valley, was long perceived as an ideal refuge for those who practiced the occult: the legends about the witches of Valcamonica are famous. Contributing to its fame was the isolation of the villages hidden among the forests, the persistence of ancient pagan rituals and widespread ignorance that fed deep fears. The Tonale Pass, in particular, was thought to be a favorite place for nocturnal gatherings: during thunderstorms, witches were said to gather around large fires. In the early sixteenth century, the valley was then rocked by at least two fierce waves of persecution. During the third wave, between 1518 and 1521, between 62 and 80 women accused of witchcraft ended up at the stake, with charges including causing drought, spreading disease among people and livestock, and performing spells of various kinds. In truth, the origin of the inquisitorial obsession was rooted in pagan beliefs, especially Roman ones, which had retained a strong cultural hold in the valley.

Trials of alleged witches had already begun in 1455, with subsequent waves of persecution in 1510-1512, 1516-1517, and then the climax of 1518-1521. The situation degenerated to such an extent that Pope Leo X was forced to intervene: on February 15, 1521, he urged the Venetian bishops to curb the judicial excesses. A few months later, on July 31 of the same year, the Venetian Republic decided to halt inquisitorial activity in the valley. At the same time, Valcamonica has come into prominence for its cultural and natural heritage: in 1979UNESCO recognized its rock carvings as a World Heritage Site, while in 2018 the entire valley was officially designated as a biosphere reserve, a recognition that indicates the importance of preserving the area in many ways.

The hamlet of Bindo, in the municipality of Cortenova (Lecco), is home to Villa De Vecchi, known as the Red House, a now-ruined 19th-century villa known among mystery buffs. Designed in themid-19th century by painter and architect Alessandro Sidoli (Cremona, 1812 - Milan, 1855) and commissioned by Count Felice de Vecchi, hero of the Five Days of Milan, the villa was distinguished by its red color and oriental inspiration. It also originally included an astronomical observatory on the third floor, which was never built, and a fountain in the garden, which has now disappeared.

Abandoned and shrouded in vegetation, the mansion attracts visitors intrigued by legends of ghostly presences: some stories speak of the murder of the count’s wife and the disappearance of his daughter, others of a murdered mistress. In any case, according to official sources, De Vecchi died unmarried and had no children. Rumors of suicides and murders are unconfirmed, and over the years have been repeatedly debunked. In the 1920s, the villa reportedly briefly housed Satanist Aleister Crowley and his followers. In fact, Giovanni Negri, son of the last janitor, denied all the dark legends. Nevertheless, Villa De Vecchi retains a dark charm that resurfaces especially on Halloween.

The Visconti Castle of Trezzo sull’Adda (Milan) stands on a promontory surrounded by the Adda River, a strategic position already exploited by the Lombards. In the 12th century , Frederick I, known as Barbarossa, built a fortress there, from which expeditions against the Lombard Communes departed, including the one that led to the destruction of Milan. Legend has it that the emperor’s treasure is still hidden in the castle. Between the 13th and 14th centuries the area was the scene of clashes between Guelphs and Ghibellines, then between Visconti and Torriani. Between 1370 and 1377 Bernabò Visconti built Castel Nuovo on the remains of the earlier fort: an imposing structure with dungeons, tower and a bold single-arch bridge over the river, now in ruins. Bernabò died in the castle in 1385, according to tradition poisoned by his nephew Gian Galeazzo with a plate of beans.

The bridge was destroyed in 1416 during a siege; traces remain on the Milanese bank. The square tower, 42 meters high, dominated the area and today, after restoration, presents a panoramic view of the plains, Pre-Alps, Milan and Bergamo. In the 16th century the castle became Spanish barracks and later suffered Napoleonic occupation. To this day, obscure legends related to the Visconti family survive around its walls.

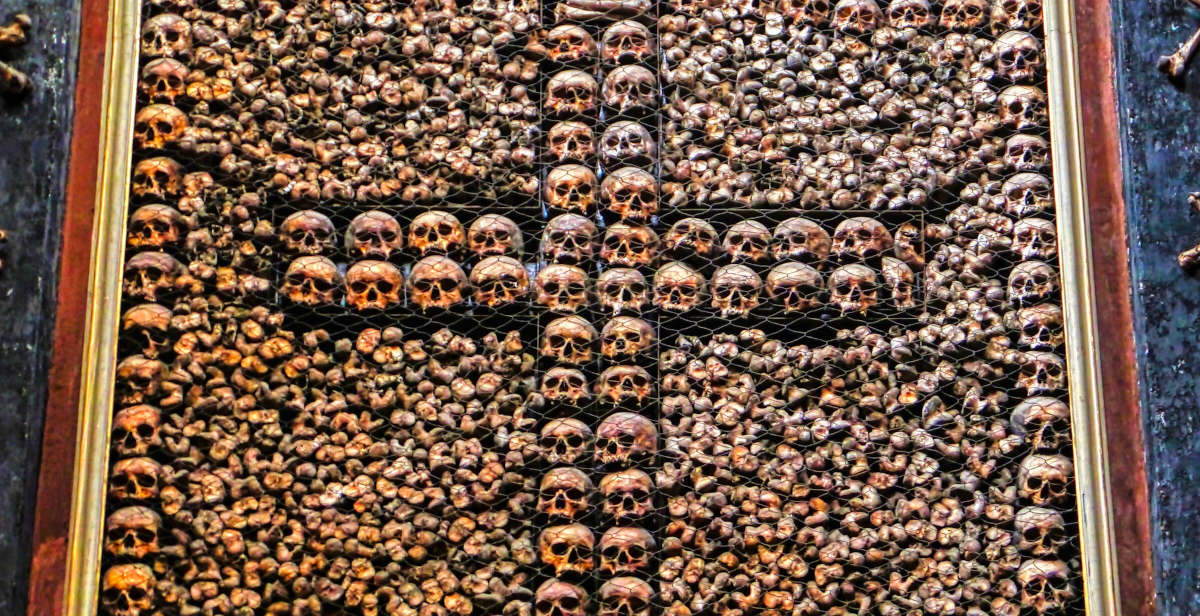

The origins of theOssuary and church ofSan Bernardino in Milan date back to the 13th century. The area was located beyond the Roman walls, between San Babila, Santo Stefano al Verziere and San Nazaro in Brolo, in a large brolo (a vegetable garden or orchard) used as a forest and garden. In 1145 the Italian presbyter and writer Gotifredo da Busserò founded a hospital near the basilica of Santo Stefano. A small cemetery was created in front, but it soon became insufficient. In 1210 a chamber was built to collect the bones. A church was built in 1268, then enlarged in 1340 by the Confraternity of the Disciplines, who added the cult of St. Bernardine of Siena. In 1642 the bell tower of St. Stephen’s collapsed, destroying the ossuary and church, which were rebuilt in 1695. The dome was instead frescoed by Sebastiano Ricci (Belluno, 1659 - Venice, 1734) in 1693 and 1694.

The bones were rearranged inside the niches, along the cornice, on the pillars and around the doors, composing a decoration in which the macabre element binds, even today, with the elegance of Rococo taste. A statue of Our Lady Dolorosa de Soledad (St. Mary of Sorrows) was inserted in a niche in the center of the only altar, made of fine marble and decorated with symbols of Christ’s passion: she wears a white surplice covered by a black mantle embroidered in gold, with her hands clasped and kneeling beside the body of the dead Jesus. The sculpture, the work of architect Gerolamo Cattaneo (Novara, 1540 - Brescia, 1584) dating from the mid-18th century and commissioned by Clelia Grillo Borromeo during Spanish rule, is reminiscent in style of the sacred images kept in churches in Seville, Toledo and other Spanish cities.

Popular worship later transformed the building into theOssuary of the Innocents. In 1750 the present church was built, incorporating the old one as an atrium. The complex passed to the Royal State Property in 1786 and returned to the church in 1929. The interior contains paintings, altarpieces, a crypt with Discipline burials and works related to Columbus and the cult of the cheese makers. In 1738 King John V of Portugal wanted a copy in Evora, near Lisbon. The entire complex was restored between 1998 and 2002.

|

| Charnel houses, witches and castles: 6 chilling places to discover in Lombardy |

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.