by Redazione , published on 10/09/2020

Categories: Travel

/ Disclaimer

The village of Loro Ciuffenna is located in the Arezzo Valdarno, in an area dotted with Romanesque parish churches. The oldest mill in Tuscany is located here, and there is also considerable artistic evidence here, from the Romanesque to the 20th century.

“Loro” is the real name of the village, the one attested since the Middle Ages: it comes from “laurus,” laurel in Latin. “Ciuffenna,” on the other hand, is the name of the stream that washes it. "Loro Ciuffenna " officially became the name of the village from 1863, following a resolution of the town council at a meeting on December 6, 1862. The origins of this village go back to Etruscan times, when the entire Valdarno territory was flourishing with trade: the name of the stream is clearly of Etruscan derivation, a sign that this area was anciently inhabited, but nothing remains of a possible settlement. To have certain evidence of Loro it is necessary to wait until 1059: in a document, the Guidi counts, who dominated the territory, turn out to be the tenants of the feud. Life in these parts flows quietly, except for the occasional raid by the armies that, between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, traveled through central Italy from high to low and vice versa, and the village therefore has a way to develop: Loro, close to Florence, the fertile Valdarno plain and the ancient route of the Cassia road connecting Rome to the Tuscan capital, was a strategic center for the Florentines, who in 1293 revoked jurisdiction over the area from the Guidi counts and invested considerable resources in modernizing and enlarging the village.

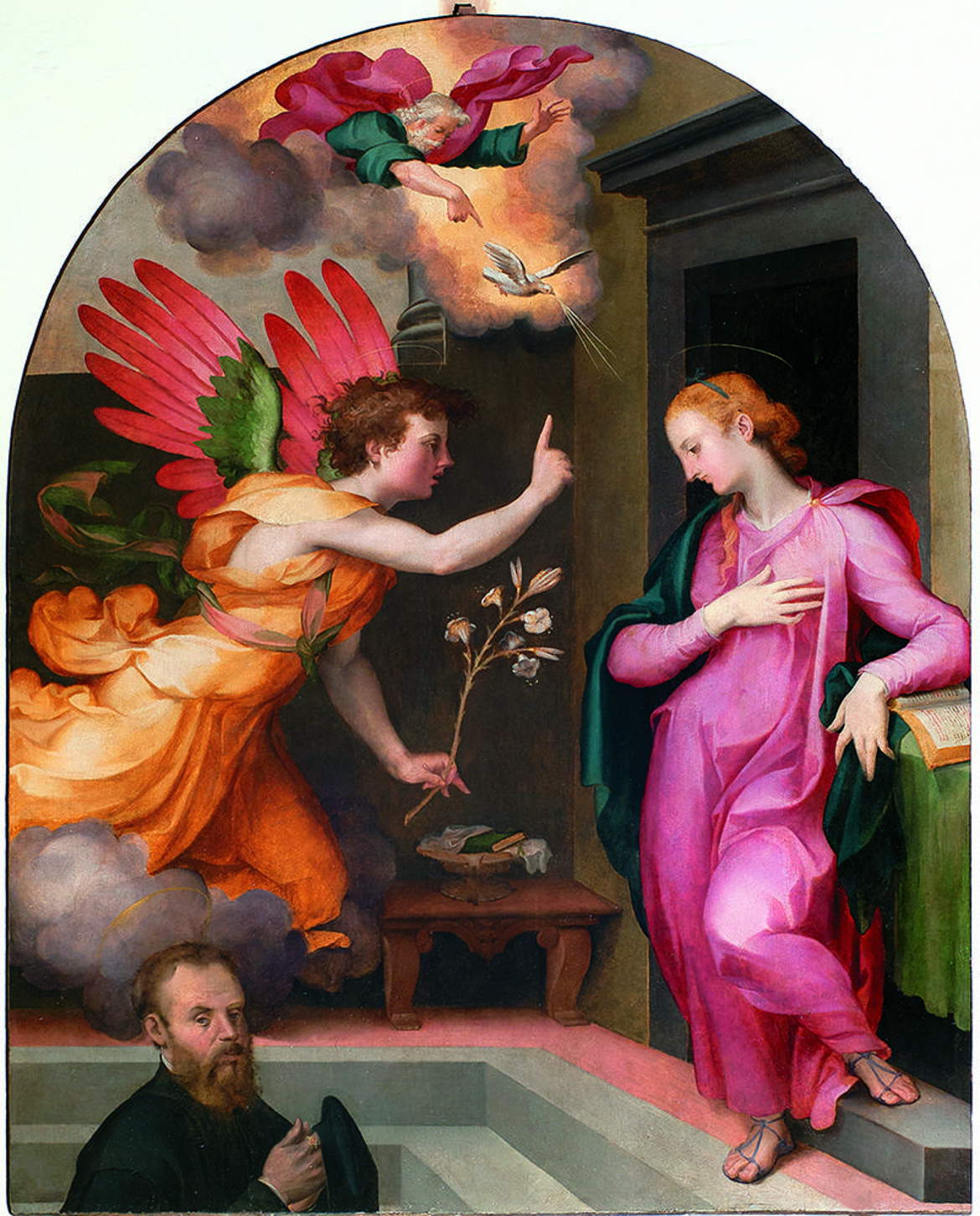

Significant medieval testimonies, in this village on the slopes of Pratomagno, there are practically none left, erased by the passage of time. A few traces of the castle remain, which can still be glimpsed among the dwellings in the highest part of the village. What has remained is the watermill, in all probability the oldest in Tuscany (dating back to the 12th century): it was used to grind chestnuts to obtain the typical flour of the area, and is still in operation today, as well as open to visitors. And the hump-backed stone bridge that crosses, very high, the Ciuffenna has remained: this one even dates back to Roman times, although it was extensively remodeled in the Middle Ages. We no longer see the ancient gateway to the village, now converted into a clock tower, painted bright red. There is, however, the church of Santa Maria Assunta, which was originally the castle chapel of the Guidi family: the layout is still that of the thirteenth century, and inside are preserved fragments of frescoes from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and above all two panels, an ’Annunciation and a Pietà, by one of the most underrated geniuses of sixteenth-century Tuscany, the mannerist Carlo Portelli, one of the most eccentric and original personalities of his time. He too was probably a native of Loro Ciuffenna.

|

| View of Loro Ciuffenna |

|

| The medieval mill |

|

| The bridge over the Ciuffenna River |

|

| The church of Santa Maria Assunta |

|

| The Annunciation by Carlo Portelli |

There remained, of course, what all guidebooks call “atmosphere.” Heightened by the particularity of the place, since the village is wedged in a gorge at the beginning of the Pratomagno, and the Ciuffenna, creeping between the dwellings, forms little waterfalls and flows between high rock walls and small steep overhangs. The Middle Ages that all travelers seek are perhaps to be found outside the village, in the area’s many parish churches, beginning with the best known, the parish church of San Pietro a Gropina, not far from Loro, a bare and sober example of Romanesque architecture that is among the best preserved in Tuscany. It is mentioned as early as the eighth century, but its construction dates back as far as three centuries earlier: an unfounded popular tradition attributes its foundation to Matilda of Canossa, but beyond the community’s fantasies it is more interesting here to note how Loro’s central position in the exchanges between the north and south of the peninsula made the parish church of Gropina one of the most extraordinary in the area (just take even a quick look at the pulpit of Lombard culture, carved at the time when Tuscany, like much of Italy, was part of the Lombard kingdom): the church was a resting place along the trades that affected this area of Italy and thus had to ensure an adequate welcome for wayfarers and pilgrims. The parish church of Gropina is located a short distance from Loro, at the end of a road that leads into the midst of olive and chestnut trees, bordered by low dry stone walls. And not far away, still in the countryside and hills, other parish churches dot the area: the abbey of Sant’Andrea, the 17th-century sanctuary of the Madonna dell’Umiltà, the small Romanesque church of the Assunta at Poggio di Loro, and the parish church of San Giustino.

Back in the village, one cannot fail to pay homage to another great artist born in Loro Ciuffenna, Venturino Venturi, to whom a museum has been dedicated (the Venturino Venturi Museum, in fact), which houses ninety-two works, including sculptures and drawings, that testify to fortyyears of activity of the great artist who had trained in Florence, becoming friends with Ottone Rosai, Eugenio Montale, Mario Luzi and Vasco Pratolini, and had then studied in Milan, in contact with Lucio Fontana and other leading artists of the time. He is best known for having won, in 1954 (four years after his participation in the Venice Biennale), the competition for the Pinocchio monumental park in Collodi, for which he would create his masterpiece, the small mosaic square. “Of Venturino Venturi,” wrote Mario Luzi himself, “I was struck from the first approaches by the form, the breath of creative elementarity. I believe even today that therein lies the cause of his powerful fascination. There are artists who spontaneously repropose nature and the principle of art, that is, they refer back to the origin of its phenomenon. They are not uncultured artists, but culture has no mediating task in them, rather it empowers and liberates a disposition so simple, so little decomposable that it coincides with the first necessity that presides over the existence of art.” And this was Venturino Venturi’s art: to bring sculpture back to its primary dimension. And his sculptures today are not only in the museum, but also in the village: the monument to the resistance, for example, recalls the tribute paid by Loro Ciuffenna during World War II. Even the smallest villages never escaped the course of great history.

|

| The parish church of San Pietro in Gropina |

|

| The interior of the parish church of Gropina |

|

| The pulpit of the parish church of Gropina |

|

| The abbey of Sant’Andrea |

|

| The Venturino Venturi Museum |

|

| The monument to the human family in memory of the Resistance, by Venturino Venturi |

Article written by the editors of Finestre sull’Arte for UnicoopFirenze’s “Toscana da scoprire” campaign

|

| Loro Ciuffenna: in Valdarno among hills dotted with Romanesque churches |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.