Between 1981 and 1986 Aligi Sassu (Milan 1912 - Pollença 2000) made one hundred and thirteen acrylic panels (a selection of which has been brought to the exhibition at the Museo Civico delle Cappuccine in Bagnacavallo, until January 9, 2022), dedicated to Dante’s Divine Comedy, divided as follows: forty-three onInferno, thirty-five on Purgatorio and thirty-five on Paradiso, taking into account that various cantos were the inspiration for multiple depictions. However, the works on the Comedy that Sassu completed over a period of six years can be considered a transposition, that is, a rewriting of the literary text in another artistic language, rich in echoes and references but with some artistic license, depending on the subjectivity of the painter. Also because in front of Dante’s masterpiece he feels a kind of parallelism with his own expressive experience, as well as a push toward a reflection on his own painting. The bodies of the damned, sinners and blessed become pure color and everything is fully expressed through form and the use of light, through a particular depiction of the masses that stand out by contrast.

This complex and elaborate project is due to the proposal made to the artist to illustrate the Divine Comedy on the occasion of a fine large-format edition, which, by contrast, was never accomplished. After spending six years “of feverish elaboration, of reflections, of readings, of fixed thoughts,” between pencil sketches, watercolor pencils and watercolors to study and create the plates that have come down to us, Sassu wrote in 1987, in his text My "Divine Comedy,“ ”The Divine Comedy has been for me a burning flame, a reading, a lived participation that I have cultivated for many seasons, something that has become a mirror of my soul and my work for years."

This was not the first time he had engaged inDante illustration: back in 1960 the Rome Quadriennale had invited artists to interpret one or more passages from the three Cantiche of the Comedy. This had resulted in a traveling exhibition, entitled Homage to Dante by the Italian Artists of Today, which had involved fifty-two contemporary Italian artists and had featured one hundred and fifty-two works on paper. On that occasion Aligi Sassu had presented three drawings, two focused onInferno, specifically on the 9th canto, Il messo celeste, and the 14th canto, Capaneo, and one focused on Purgatory, specifically on the 10th canto, La giustizia di Traiano. The exhibition toured Europe for a good five years, and the works on display formed the illustrative corpus of the edition of the Commedia published by Aldo Martello in 1965 in five hundred copies. In the same year, which marked the seven hundredth anniversary of Dante’s birth , the Ministry of Education acquired these works and temporarily deposited them in the National Museum in Ravenna. Sassu also participated in another initiative on Dante in 1965: Ravenna involved twenty artists who were asked to make sketches for celebratory mosaics; the exhibition was set up in the former Scuderie del Complesso di San Vitale, and Sassu brought a panel dedicated to the last canto of theInferno depicting Lucifer (today the preparatory cartoon is kept at the MAR-Museo d’Arte della città di Ravenna, while the respective mosaic was made by Giuseppe Salietti).

Even before the traveling exhibition and the Ravenna initiative, the artist had also dedicated in the 1940s some lines of one of his poems, L’atroce soavità dell’Inferno, to the figure of Minos, “chained guardian” and “fierce servant of life.” Pictorially, the inspiration for scenes from The Divine Comedy came from his passion for nineteenth-century French painting: Eugène Delacroix ’s The Boat of Dante and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Paolo and Francesca were sources of inspiration. However, there is something deeper in him about Dante: it is an inner approach, delving into his own sufferings and struggles for freedom. He, too, learned what it meant to be imprisoned: it was April 6, 1937 when OVRA police raided his studio and found the manuscript for an insurrectionist manifesto. He and other comrades were accused of plotting and arrested; he was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment, serving eighteen months in the prisons of San Vittore, Regina Coeli and Fossano. It was the king who granted him a pardon thanks to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who interceded with Mussolini.

"It was not like when I illustrated Lazarillo de Tormes or Poliziano’s Stanze, the Gospel of St. Mark or theApocalypse,“ he had declared. ”Something totally different. A text that offered me a reading, a conquest, a continuous struggle for the light of painting, of form, of discovering the mystery of Dante’s words linked to universal examples of the human condition.“ A universal human condition that refers back to history contemporary with him. ”I did not want to translate Dante into images [...] It was instead a continuous invention of images ... humbly listening to Dante’s words, in order to be able to understand their unparalleled chromatic power,“ he explained. ”I tried to give substance to my ideals of struggle, against the mad bestiality that has always been latent in man." It is in this sense that Sassu’s panels are to be seen: an ongoing meditation on the existential journey of each individual, which is expressed here through strong chromatic tension.

Underlying the panels dedicated to Dante is a profound knowledge of the text: he does not allow himself to be seduced by descriptions of infernal punishments, as other artists had done; his approach is to depict the Divine Comedy as a human poem, among souls who have emotions and feelings. Just as for Dante the journey to the afterlife is a cause for reflection, for Sassu the representation of the Comedy, at the threshold of his seventies, leads him to reflect on his own existence, to look back over his artistic life, “a mirror of my soul of my work for years.”

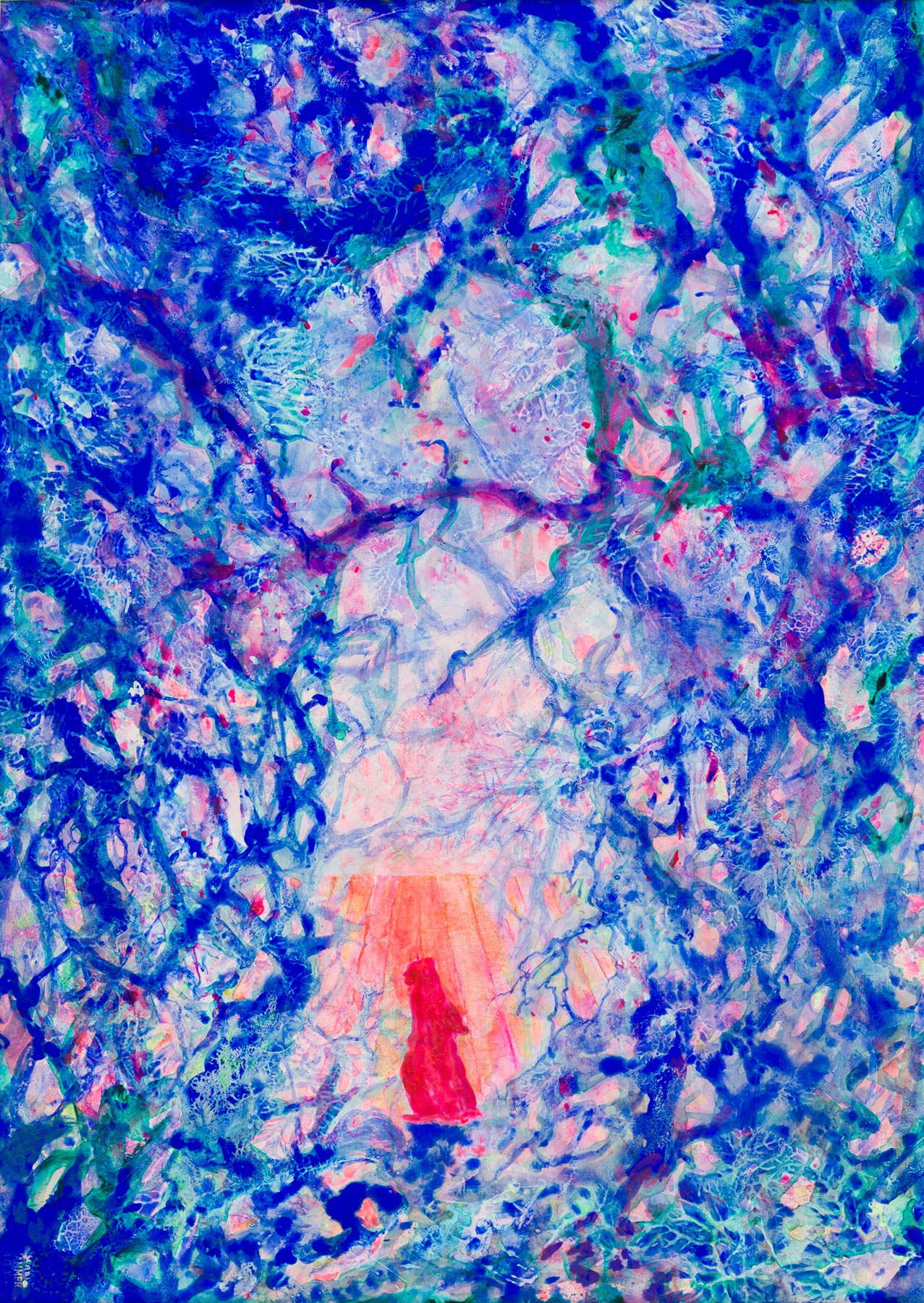

Just as the first canto ofInferno serves as a proem to the entire Commedia, the panel dedicated to this canto can also be considered an introduction to the entire cycle. Sassu’s dark forest indicates that we are about to enter a world of bright colors, alluding to the musicality of the triplets. Blue in color, the Sassu forest is a metaphor for spiritual death: in fact, the artist associates all cold colors with everything negative in life. Instead, red is the dominant color in his painting; red like Dante’s cloak. The background, with which the characters seem to merge together, also takes on significance: this recalls an idea of identification between the figures and the background, between the soul with its sinful or virtuous inclinations and the assigned place: “a criterion of expiatory adjudication... Fire, then, caloric temper that arises from the soul, which expands on the destiny of individuals, to lead them spontaneously to the right assignment.”

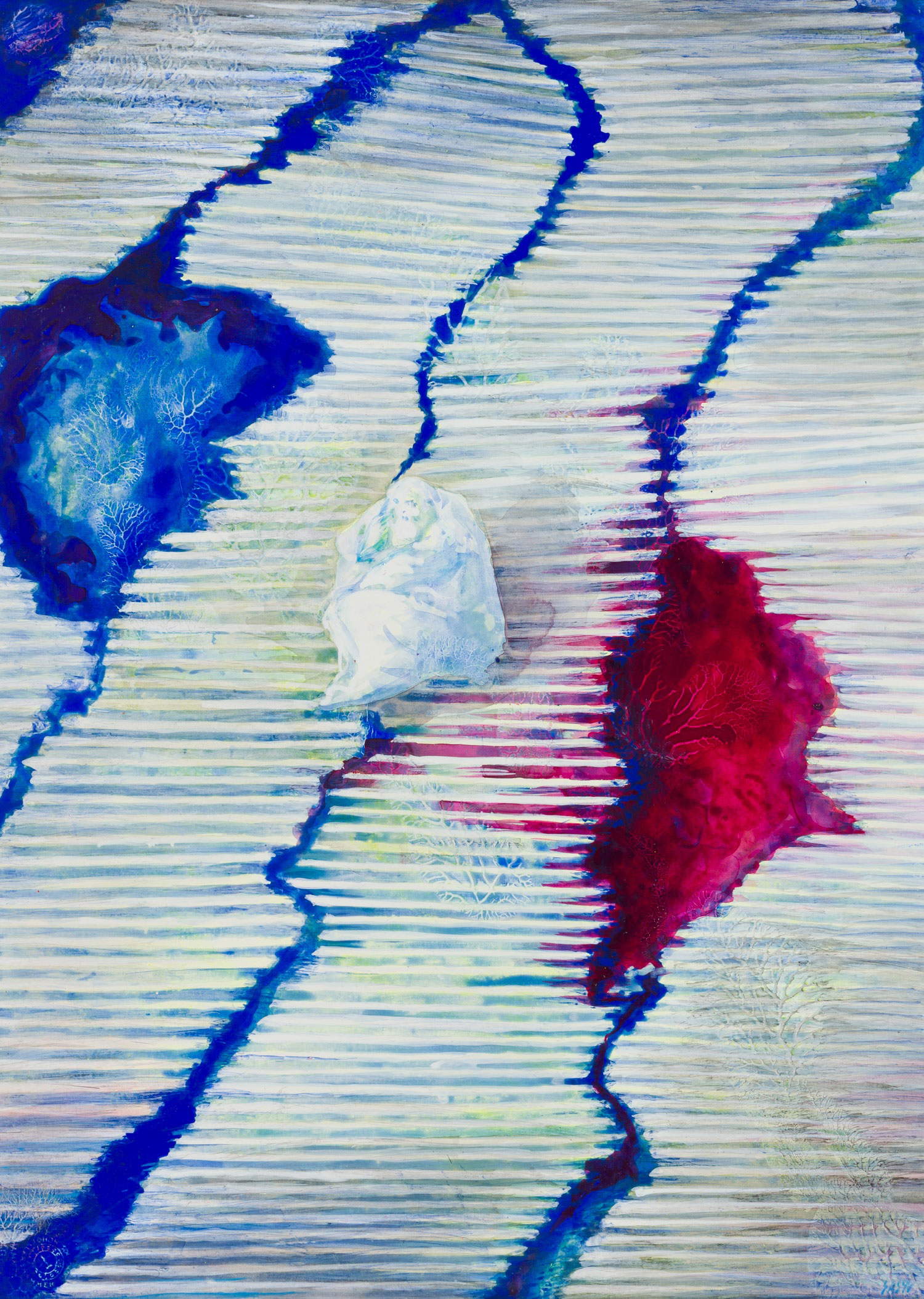

“Bodies interpenetrate, merge like infernal or heavenly or purgative larvae into an amalgam created by the intertwining and merging of souls that are born and die in the body of color,” he wrote in My "Divine Comedy.“ ”Making color leaven, with light breaking and fraying the forms, red interpenetrating with green, blue with yellow and carmine: it is fire, a fabric is created, an interweaving of the various colors in a sulfurous magma that intensifies each other. A simmering of similar and contrasting colors is created, thus giving the sense of a vital ferment." A clear example of this is I lussuriosi, Canto XXV Purgatorio, where the characters within a single background that turns from purplish red to orange occupy almost the entire painting, propagating and advancing like a glowing magma. On the other hand, with the same principle but more defined are the souls that Dante encounters in Canto II of Purgatory: the entire composition is occupied by bluish characters and background, while Dante with his red cloak stands out on the left.

Sassu often devotes more than one panel to a mythological subject, revealing a certain attention to myth: this is the case of Geryon , whom the artist depicts in the seventeenth and eighteenth canto ofInferno, in the form of an isolated figure. Not only magmas of figures, but also figures in their own right, such as the beautiful Archangel Gabriel in the 14th canto of Paradise.

Dante has been very present in Aligi Sassu’s artistic activity; therefore Bagnacavallo wanted to pay homage to the ideal dialogue between the artist and the Supreme Poet in a single exhibition project, on the anniversary of the seven hundredth anniversary of Alighieri’s death.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.