Like Dante Gabriel Rossetti ’s The Bride (London, 1828 - Birchington-on-Sea, 1882), every bride on one of the most beautiful days of her life wants to be the protagonist, the center of attention; she wants to look the most beautiful, and so she prepares everything down to the smallest detail: her dress, her hairstyle, her ornaments, and her face must be perfect. This is the context that the great Pre-Raphaelite painter wanted to capture in his canvas: a young woman about to be married. She has already put on her gown, which is not white as we would expect a bride to be today, but on the contrary is characterized by an emerald green color with floral decorations, the latter visible especially along the wide sleeves, and by a particular taste for the exotic, as can be seen in the fabric of the dress, which resembles that of a Japanese kimono.

With a delicate gesture of both hands, one of which, the left, is embellished with a gold ring, she is removing the veil from her face: a veil still in shades of green, darker with lighter weaves, revealing a bewitching, enchanting, and at the same time seductive face. Light green eyes set in an almost ethereal face with a moonlight-like complexion and a very slight blush on the cheeks, full red lips, all with a very natural and refined effect; wavy red hair that is probably long, from what can be perceived from the hairs coming out of the veil, further illuminates the face, and a large oriental-style bow in shades of red and yellow presumably holds the veil to the head. What is overpoweringly striking, however, is the spellbinding gaze that the bride directs toward the viewer, whether it is the public visiting the Tate Britain in London where the work is housed, or the groom himself: in this case, the viewer would be in the point of view of the betrothed, at the moment when, facing each other, the bride uncovers her face, making all her beauty manifest. And her piercing green eyes that, venturing a comparison with another young woman who became famous for her magnetic gaze, recall those of the Afghan Girl in the photographic portrait done by Steve McCurry in 1984. Two completely different situations that have nothing to do with each other, but in their subject matter have striking similarities.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s TheBride dates from 1865-1866, toVictorian-era Britain, although it was precisely the latter’s principles and ideals, particularly morality with all the impositions attached to it, that were unhinged by the Pre-Raphaelites, of which Rossetti was among the main founders along with William Hunt and John Everett Millais. In fact, the movement was born from the three artists, who founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: united by their training at the prestigious Royal Academy in London and thus by painting that had to submit to the Academy’s strict and restrictive rules, they decided to devote themselves to an art inspired by the Middle Ages and its legends, the great Arthurian and chivalric cycles, biblical themes, and the literature of their favorite authors, namely Chaucer, Shakespeare Tennyson and Dante Alighieri (Rossetti’s very name is due to the artist’s father’s passion for the divine poet, of whom he was a scholar, which he had also passed on to his son, so much so that he also translated works by the man of letters), and finally by a return to nature imbued with mysticism, which thus distanced itself from the interest of the time in factories and the advent of the industry.

That of the Pre-Raphaelites, as the name suggests, was an art that took as its model the painting preceding Raphael Sanzio: in fact, the Urbino artist was considered the antithesis of the painting popularized by the Pre-Raphaelites because it was too virtuous and too detached from the truth of nature. Dante Gabriel Rossetti had the opportunity to get acquainted with the Italian painting of Perugino, Beato Angelico, but also with the portraits of Titian and the Venetian painters of the 16th century, such as Palma the Elder, Veronese, finding inspiration to portray female characters. His portrayed women responding to Pre-Raphaelite taste are sensual, seductive, and beautiful women, in line with theAesthetic Movement according to which every art form was to represent beauty. Women like the one depicted in The Bride, with the lightest skin as was the ideal of beauty at the time, voluminous, red hair, and fleshy mouths: traits that embodied modern beauty. These are female figures who are aware of their charm and sensuality and who therefore dominate the entire scene: the bride is at the center of the composition, extraordinarily beautiful, surrounded by her four handmaids, all of whom have wavy, dark hair unlike the protagonist. They all look toward the viewer, except for the one depicted on the right, whose face is in profile, and their skin is darker than the bride’s ethereal complexion, especially the two handmaids half-hidden behind the latter. Regarding this aspect, Rossetti may have been inspired by a verse from the Song of Songs, “I am brown, but I am beautiful, O daughters of Jerusalem, like the curtains of Kedar, like the curtains of Solomon”(Song of Songs, 1:5).

Red hair is almost the hallmark of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s women, often accompanied by the very light complexion, as in Dante Alighieri ’s Beatrice in Beata Beatrix, a work the painter created as a tribute to Elizabeth Siddal (London, 1829 - 1862), his companion and model, poet and painter, who died prematurely at an early age. Or in the imposing Aurelia (The Lover of Fazio), depicted braiding her long, fluffy hair in front of a mirror-a portrait most likely influenced by Titian’s Woman in the Mirror, which the painter knew well because he owned a photograph of it. The model in this case was Fanny Cornforth, a woman with whom Rossetti had a relationship and whom he also depicted in Lady Lilith.

Often the women portrayed were real models, and some of them can be recognized in The Bride as well: the handmaid on the left in the foreground has the likeness of Ellen Smith, a young washerwoman of whom the painter was particularly fond; the second on the right is probably Fanny Eaton, a maid of Jamaican descent; and the bride has the features of another friend of the artist, Marie Ford. In the very foreground, on the other hand, a black child is portrayed, adorned with jewelry and holding a vase of roses, further highlighting the taste for the exotic. The work is also enriched with symbols: the roses symbolize beauty, while the red lilies held by the handmaids symbolize purity, but at the same time also the loving passion for color. They also refer to a verse in the Song of Songs that reads, “My beloved is mine and I am his, he shepherds his flock among the lilies”(Song of Songs, 2:16).

The painting was inspired by the Song of Songs, a text from the Bible and also known as the Song of Solomon, as it is attributed to theancient king of Israel, who was known for his songs and loves. The Canticle recounts the love between a man and a woman, and the beauty of the bride is specifically extolled.

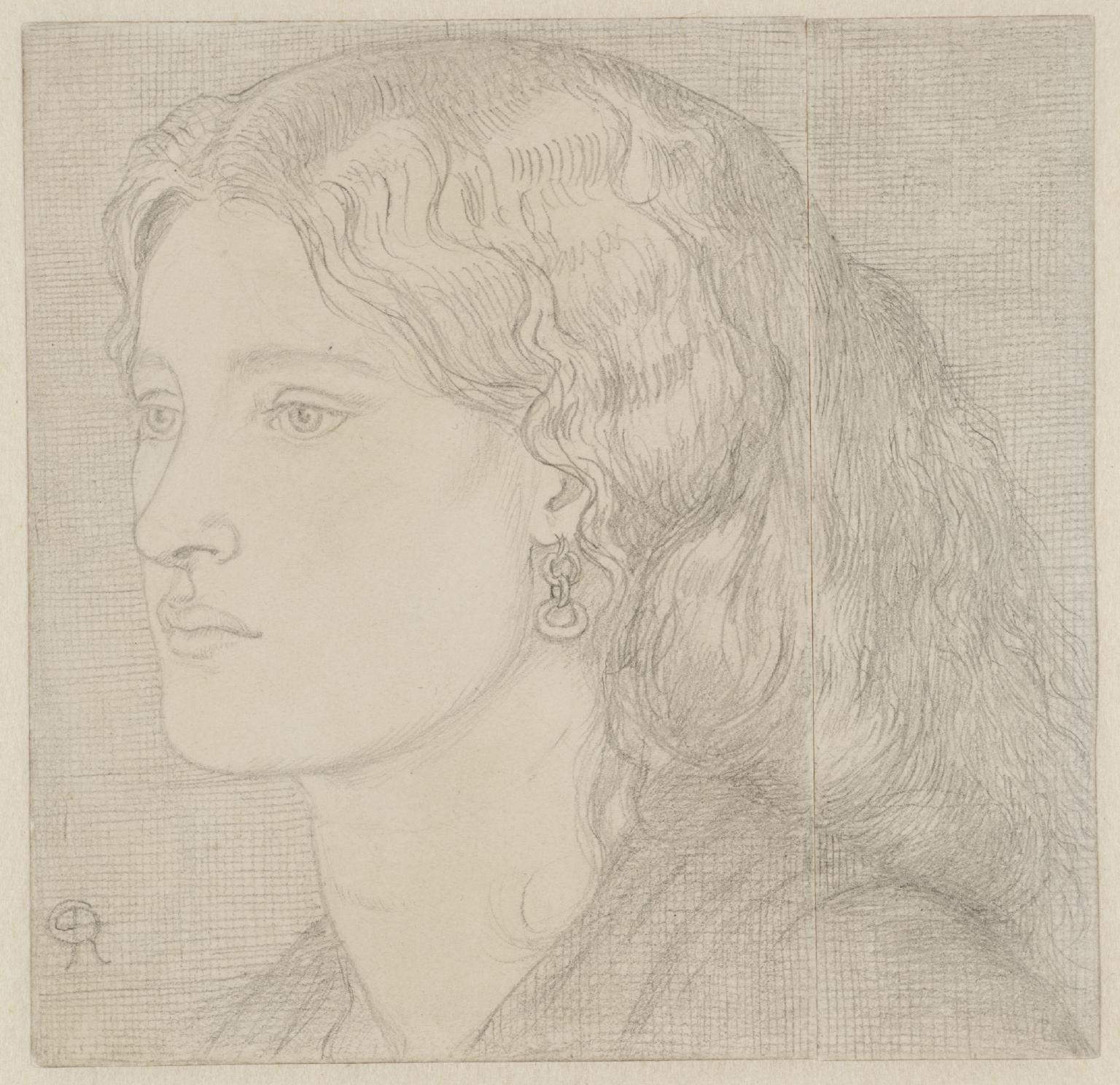

Commissioned in 1863 by banker George Rae, the work was originally designed as a portrait of Beatrice for Ellen Heaton, a philanthropist and art collector famous for her support of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In fact, Rossetti wrote a series of letters to Heaton in which it is understood that the painter began to conceive the image, still in the study phase of the work, as “the bride of the Song of Solomon”: “The present Beatrice is to be transformed into the Bride of Solomon, a theme on which I delight and which has always fascinated me. I shall call her The King’s Daughter, and you will find that she will be as beautiful an image as the other, indeed better. I think you will be tempted to keep it, but if not, I will instead paint you a Beatrice whenever I can find a really suitable model. ” A graphite study of The Bride is also preserved at Tate Britain, depicting a beautiful young woman looking intently at the viewer, already with a slight veil on her head.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’sThe Bride is a fascinating and bewitching work, beautifully imbued with the ideals and artistic principles of Pre-Raphaelism. And her intense and piercing gaze makes her for all intents and purposes a modern woman aware of her charm, almost as if it were a

photographic shot, capturing the moment when a bride lifts her veil revealing, to the surprise of onlookers, the beauty of her face.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.