According to a widespread critical interpretation, the unfolding of English drama between the reign of Elizabeth and that of James I can be divided into three phases, corresponding to different conceptions of life. Early Elizabethan drama (Robert Greene, Thomas Kyd, Christopher Marlowe) expresses the boundless confidence in human genius and enterprise characteristic of a youthful and dynamic age. Already in Marlowe, however, there is a sense of disappointment that anticipates the spiritual despondency of the second phase (1598-1611), connected with the fading of the traditional worldview under the blows of the new science and the perception of impending political catastrophe. The result is the great dramas dominated by cynicism and pessimism: Troilus and Cressida, Hamlet, The Malcontent, Volpone, The Revenger’s Tragedy, and The White Devil. This climate is succeeded, finally, by a more detached balance, where bitterness and despondency are succeeded by indifference and serenity: this is the season of Beaumont and Fletcher, The Tempest and John Ford.

Mario Praz nevertheless warns against excessive schematization. The advent of James I, rather than generating upheaval, “was a decisive factor of stability,” and modern judgment has been conditioned by a mistaken analogy with the early postwar crisis in the twentieth century. Moreover, “not enough account has been taken of how much of purely literary vogue and pose there is in the melancholy humor and cynicism that characterize so many works of the period.”

John Webster’s work fits precisely into this atmosphere. Interest in Montaigne’s Essais, translated by John Florio in 1603, “stamped the old Senecian tragedy of revenge and horror with new ways” (Praz). Shakespeare himself was probably inspired by Montaigne to delineate Hamlet’s melancholy temperament, and from here arose that figure of the bitter moralizer, embodied by Jaques in As You Like It, later spread throughout early seventeenth-century English theater.

Montaigne had expressed the disquiet arising from the new astronomical discoveries: the idea of the mutability and decay of the world, made darker by the belief that the entire universe was in decline. Similar sentiments can be found in Walter Raleigh and especially in John Donne, who wrote, “The new philosophy puts everything in doubt; the sun is lost, and the earth...men openly confess that this world is ended, when they look for so many new ones among the planets.” Through Montaigne and Donne, Webster assimilates this vaguely melancholic current, which deeply marks The Duchess of Malfi. Famous, in this sense, is the passage in which Antony contemplating the ruins states, “These ancient ruins are very dear to me...we never walk over them that we do not set our foot upon some venerable history.” The Montaignan quotation from Cicero’s De finibus is explicit: “quaecunque enim ingredimur in aliquam historiam vestigium ponimus” (“wherever we walk, we set our foot on something historical”).

The dark atmosphere of Websterian tragedies has led to his being called an “Elizabethan Edgar Poe.” But caution is needed: scenes that seem gruesome to us today may have had different value then. The famous scene of the madmen, for example, was for Elizabethan audiences an interlude of amusement, as Thomas More already recalled, “Moriones in delitiis habentur” (“madmen are funny”). Webster thus exploits a fashion, bending it to tragic ends.

Equally characteristic is the sense of the spectacular. Webster knows how to “exploit the taste of the audience of the Phoenix and Red Bull theaters, which was not very different from that which crowds our cinemas” (Praz). Hence the predilection for processions, tournaments, ceremonies, but also for scenic deaths: the poisoned painting, the infected helmet, the poison-soaked bible, the werewolf. “With Webster the theatrical vogue for Italian horrors reaches its supreme expression,” Praz observes.

In this taste for the macabre, Praz juxtaposes Webster with some Italian engravings of the early 16th century, in particular Agostino Veneziano’s Stregozzo- “a sort of black bacchanal, where gangly youths escort the most frightful of convoys: a witch huddled on a carcass next to brats, a sorcerer riding a skeletal dragon, goats attesting to the presence of the devil” - and the diabolical assembly of lamias depicted in another of his prints, for which there is a drawing by Rosso and Bandinelli. Images that seem to anticipate the ghostly scenario of Websterian tragedy. These suggestions are complemented by a further core of visual references drawn from Italian portraits of the sixteenth century, the same century in which the historical events that inspired Webster’s two tragedies take place. Bachiacca’s female portraits, with complex hairstyles and weary smiles, bend over a flower as if they themselves were exhausted; others, such as those by Bartolomeo Veneto-including the famous idealized portrait of Lucrezia Borgia-convey a sense of fascination and menace that recalls the figure of Vittoria Corombona in Webster’s works. In Bronzino’s paintings, with their chiseled figures and intensely colored, almost marble-like robes, there is a cold, melancholy elegance, a gaze that conveys oppression and disquiet. Webster transforms this kind of atmosphere, widespread in the late Italian Renaissance, with extraordinary artistic insight in his tragedies, even though he knew Italy only through indirect sources.

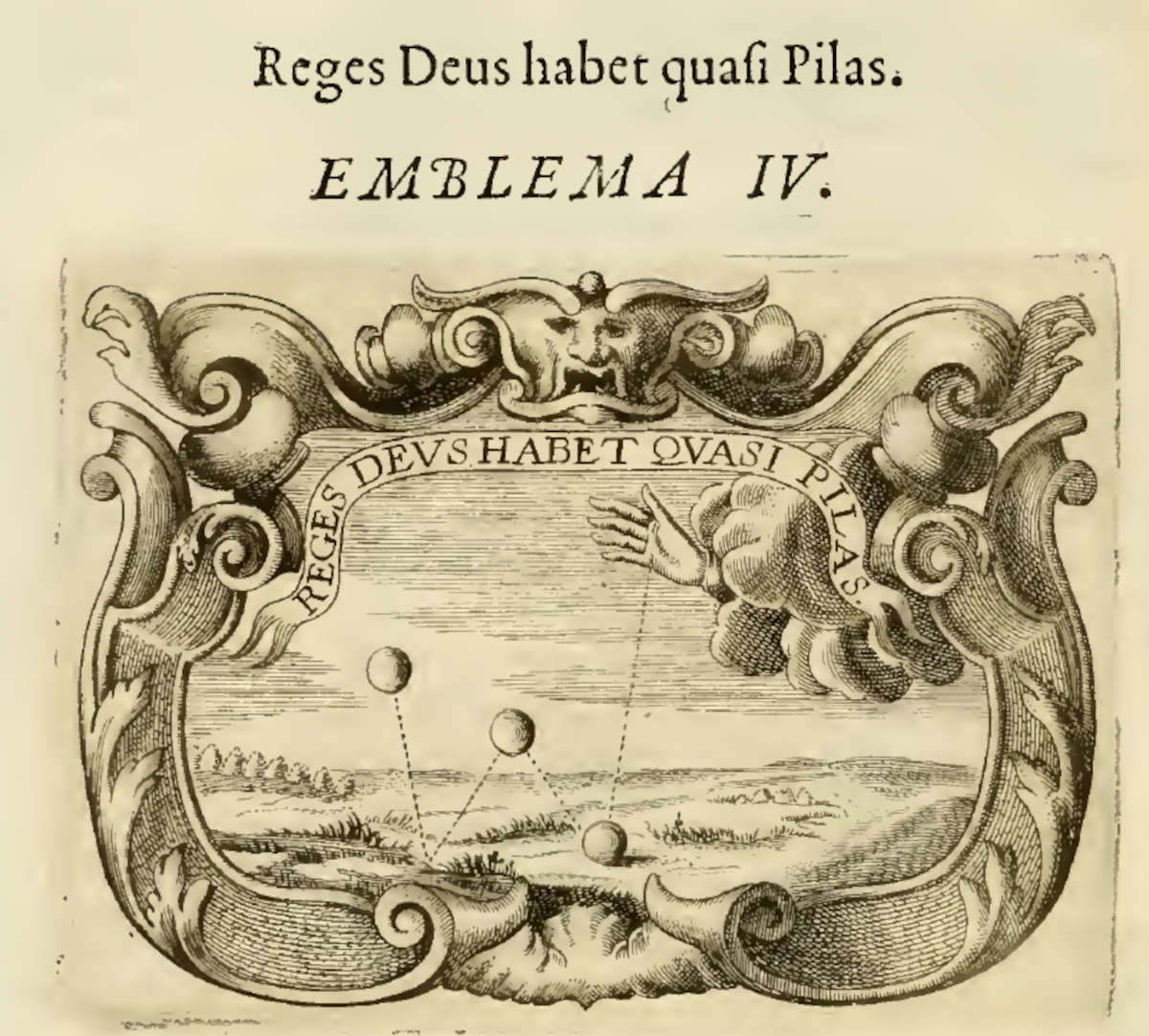

Alongside his taste for the macabre, Webster builds an articulate system of parallels and internal correspondences, reminiscent of the use of the Leitmotiv in Wagner or Ibsen. An emblematic example are the deaths of the Duchess and Antonio, united by the narrative thread of Bosola, who whispers news to each about the fate of the other. Bosola himself represents the “melancholy rascal,” whose path is marked by the ironic contrapasso of his own actions. Reflecting on human destiny, he observes, “To the stars we are but as tennis balls; they beat us and throw us where they like.” The image recalls a famous quatrain by Omar Khayyam, in which man is compared to the polo ball, a pastime of Persian knights. This metaphor is recurring in Iranian poetry, from Abu Saʿīd to Hafez, and Praz traces striking analogies in the Western tradition as well: indeed, Plautus, in the prologue of the Captives, writes “Di nos quasi pilas homines habent,” i.e., “it is indeed true that the gods take us, we men, to play ball with them.”

It is no coincidence that Bosola himself-the assassin who, in the finale, redeems himself by striking down the killers of the Duchess and Antonio-is the character charged with uttering these reflections. To him Webster also entrusts a question of intense Gnostic resonance: “The world is darkness: in what shadow, what infinite and dark well does mankind live, bewildered female?” (translation by Giorgio Manganelli).

In the volume Three Elizabethan Dramas (1959), Praz locates the direct model for the recurring image in the pages of Philip Sidney’sArcadia, where phrases such as “he quickly made his kingdome a Tenniscourt, where his subjects should be the balles” and “(mankind) are but like tenisbals, tossed by the racket of the hyer powers” recur. The same concept surfaces-we have seen-already in Plautus and will be taken up by Montaigne: “Les dieux s’esbattent de nous à la pelote, et nous agitent à toutes mains.” Thus Webster, echoing Sidney, links man’s condition to a blind and cruel fate.

The motif of the game ball does not end there. St. Teresa noted, “It seemed to happen to me to see devils playing tennis with my soul”(Vida, XXX). In Solórzano Pereira’s Emblemata (Madrid, 1651) God himself is depicted playing tennis with kings, and the image thus takes on the value of a universal emblem of human precariousness. This vision, with a vague Gnostic overtone, portrays humanity as tossed about by the wandering planets and lost in the cosmic labyrinth, and is welded with the religious and philosophical sensibility that runs through Webster’s tragedy.

In Mnemosyne (1971), Praz recognizes in the tennis ball a symbol of humanity’s destiny, even in seemingly distant contexts, such as the introduction of the curve-the so-called serpentine line-in Borromini’s architecture. Praz first notes how Baroque taste was often attracted by games of combination, by “infinite permutations around a single nucleus.” An example of this is the Dutch Jesuit Bernard Bauhuis, who in Epigrammatum libri V (1615) composed an invocation to Our Lady celebrating her virtues with the line “tot tibi sunt dotes, Virgo, quot sidera cælo” (“as many are your gifts, O Virgin, as the stars in heaven”). The philologist Erycius Puteanus, in Pietatis thaumata (1617), made 1022 variations of that verse, as many as the number of stars catalogued by Ptolemy: an entire book generated by a single verse, repeated and transformed.

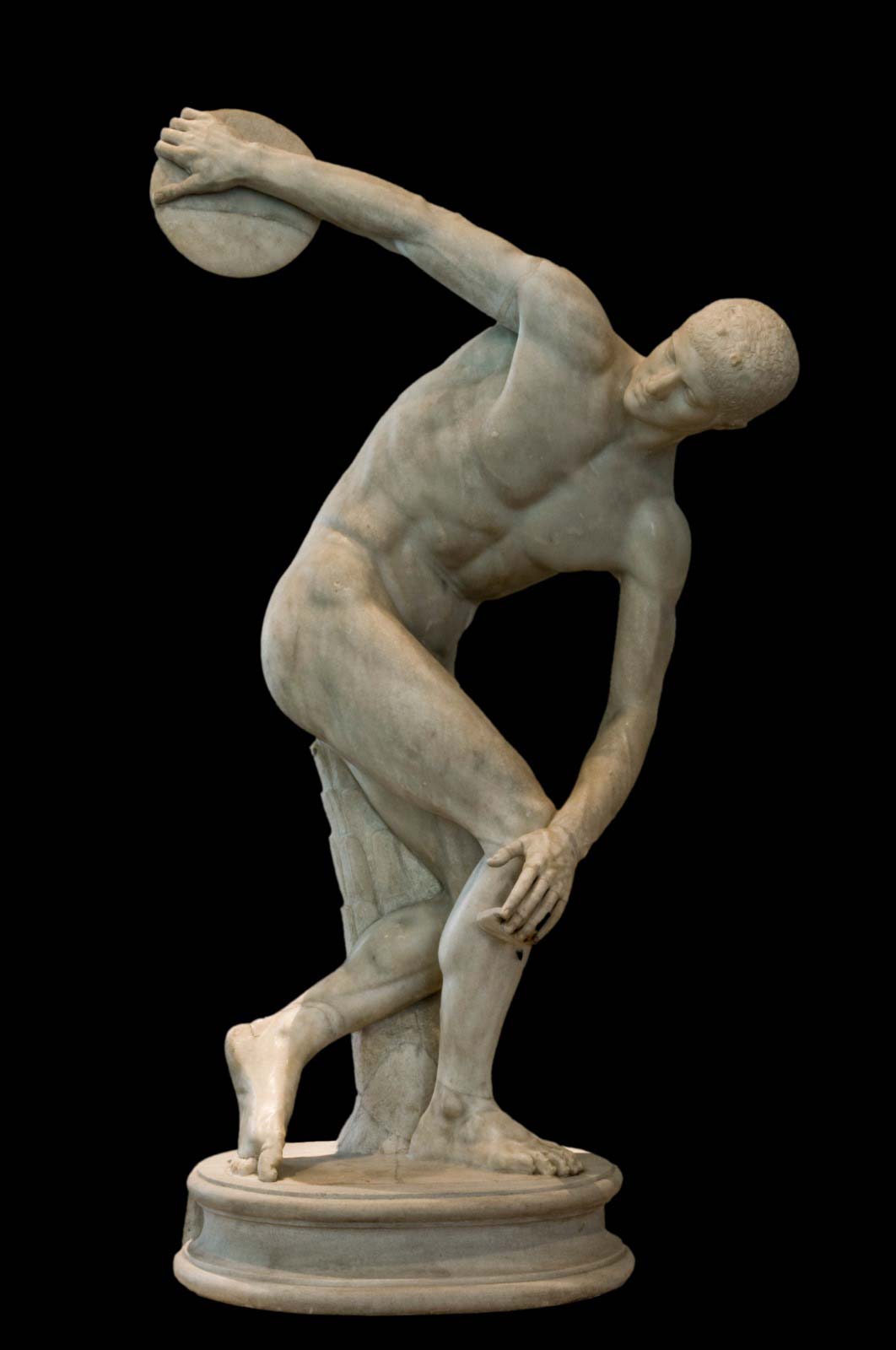

Quintilian already observed that the serpentine line possessed a virtue similar to that of rhetorical figures, which owe their grace to deviation from linearity. John Shearman, in Mannerism, commenting on Myron’s Discobolus, notes how “an impression of grace and enchantment” comes from rhetorical figures, “because they imply a certain departure from the straight line and have the merit of representing a variety from common usage.”

Borromini applied this principle to architecture, turning it into a revolutionary language. His churches-from San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane to Sant’Ivo-are built on the curve. Arches and counter-arches create a continuous rhythm that moves concave and convex surfaces, interrupts pediments and transforms the rigidity of stone into a kind of musical flow. As Praz notes, the curve “aids in the creation of an illusory space.” Various symbols are interwoven in the architectural forms: angel wings, solar spheres, clouds, palm branches, windswept draperies. All indicate movement and vitality, along with objects such as soap bubbles, eggs, hearts and, again, the tennis ball. Praz points out that it is significant that the image of man’s absolute helplessness in the face of fate or the will of a supernatural power-a central theme in the seventeenth century-finds representation in a play object such as the ball. On the other hand, the curve lends itself to be interpreted as a symbol of the precariousness of the human condition. Borromini’s architecture, characterized by curved lines and dynamic forms, can evoke a feeling of instability and transience, reflecting the human condition in a spiritual and symbolic context.

This vision of fatality, heir to Seneca, is refined by Webster until it becomes a diffuse atmosphere, a language laden with foreboding and sinister ambiguity. While the overall design may appear coarse, the poetic density of the details gives unity to the tragedies. "There is a meridian quality in the tragedy of Vittoria Accoramboni, a twilight quality in that of The Duchess of Amalfi," Praz observes. In this sense, The Duchess of Malfi represents the final phase of the Renaissance, already veiled by a sense of vanity and disenchantment. The work belongs to a “season of declining light - evening or autumn,” comparable to the climate in which Tasso’s masterpiece matured. The commonplaces of the pastoral tradition, such as the dialogue with the echo, are loaded with foreboding. The entire tragedy is tinged with “a vein of funeral elegy” that, anticipating Romanticism, also finds parallels in the figurative arts, such as Piero di Cosimo’s so-called Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci , where the traditional motif is invested with emblems of death.

The event from which Webster takes his cue is historical. As Luca Scarlini recalls in the introduction to the Einaudi edition, Giovanna d’Aragona, widowed by the Duke of Amalfi Alfonso Piccolomini, secretly married her master of the house, Antonio Bologna. The family, hostile to that union, orchestrated their elimination at the hands of the duchess’s brothers, Carlo and Lodovico, whom Webster transfigures into the characters of the Cardinal and Ferdinand. The story was told by Matteo Bandello in the novella Il signor Bologna sposa la Duchessa di Malfi e tutti dui sono ammazzati (1554), which had wide circulation and also inspired Lope de Vega with El Mayordomo de la Duquesa de Amalfi (1618). Bandello openly expressed sympathy for the protagonist, with a tone that Scarlini describes as one of “feminist afflatus.” The story was later translated and expanded by Belleforest and William Painter, eventually offering it to Webster, who reworked it by introducing new characters and motifs from Sidney, Montaigne and Donne. The Duchess of Malfi was printed in 1623 and underwent several revivals until the eighteenth century, when it was made more in keeping with the “refined” taste of the time.

In the end, like the ball bouncing under the will of the stars, man remains suspended between forces that overwhelm him, and The Duchess of Malfi reminds us of the fragility and instability inherent in the human condition.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.