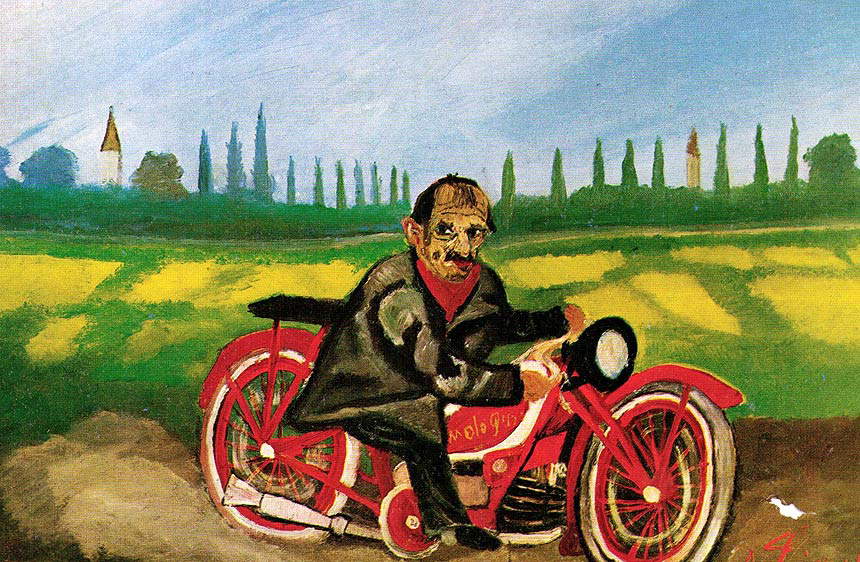

An exhibition celebrating this extraordinary motorcycle born in the 1930s opened at the Guzzi Motoraduno in Mandello, featuring Antonio Ligabue’s GTV500. Apparently, artist Antonio Ligabue (Zurich, 1899 - Gualtieri 1965) owned many of them, as many as sixteen. The fortunes of Ligabue, who also managed to be financially comfortable, thanks to the help of his friend Renato Marino Mazzacurati, who provided him with opportunities to exhibit his works, is the story of an artist ambivalently told by critics and a certain market, despite the fact that today there is the Ligabue Museum, the Ligabue House Museum, and the Archive Foundation. The first thing I notice is that in many art history textbooks he is not even present, as if this original and highly talented figure did not exist, or at least was not even worth mentioning. The result is that generations of students have never heard of him.

Yet from the RAI Teche appears, like a thunderbolt, an extraordinary 1970s documentary on the artist where, among other things, Ligabue talks a bit about himself. It can be seen on YouTube, available to all. But if few people know who he is, how can anyone be expected to seek him out? Sure, insiders know this great artist, but that is not enough.

In this TV interview you see Ligabue describing some of his feelings: he responds in his own way, at bottom a bit enigmatic, but certainly full of suggestion and dazed and fractious sensibility. Enclosed in a few frames there is also his desperation in not being able, for example, to paint a self-portrait the way he feels, the dressing as a woman, the admission that he is seeking affection, love, closeness. It is also very powerful to follow him in his immersion in the Emilian countryside with a small mirror in his hand, as he looks at himself trying to immerse himself in the likenesses and “voices” of the animals he imitates. How can one not be impressed by these images? How can one not be curious about an artist so little treated by the official culture, or even dismissed or branded by the word “naïf,” itself a synonym for primitive, naïve, a rib of the art of the “greats,” about whom passionate pages have been written? It would be interesting to retrace and redraw the history of art backwards, and this time in a manner free from dogma, from incontrovertible absolutes. High art and low, popular art, then, and we go on as if nothing happened.

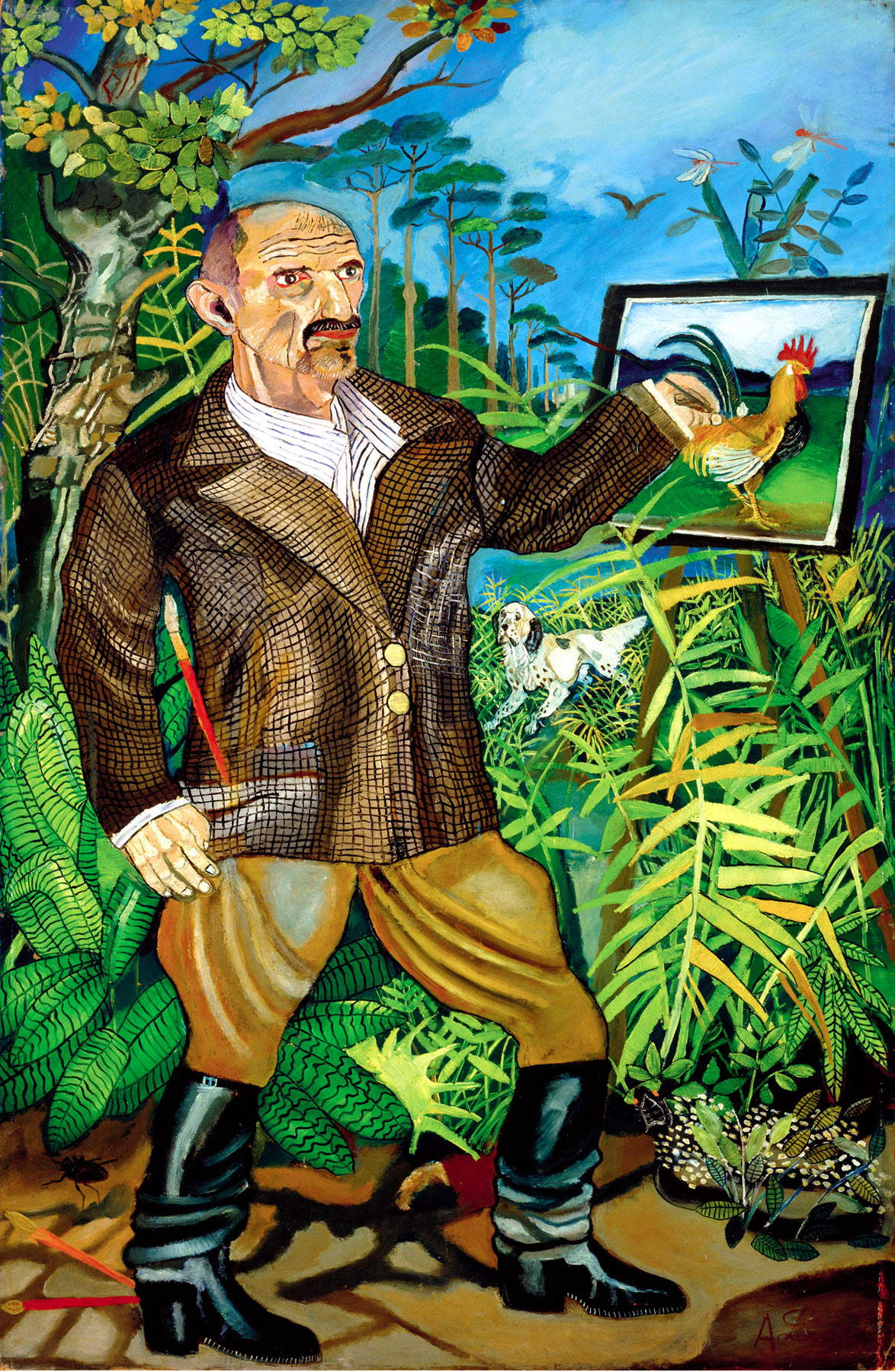

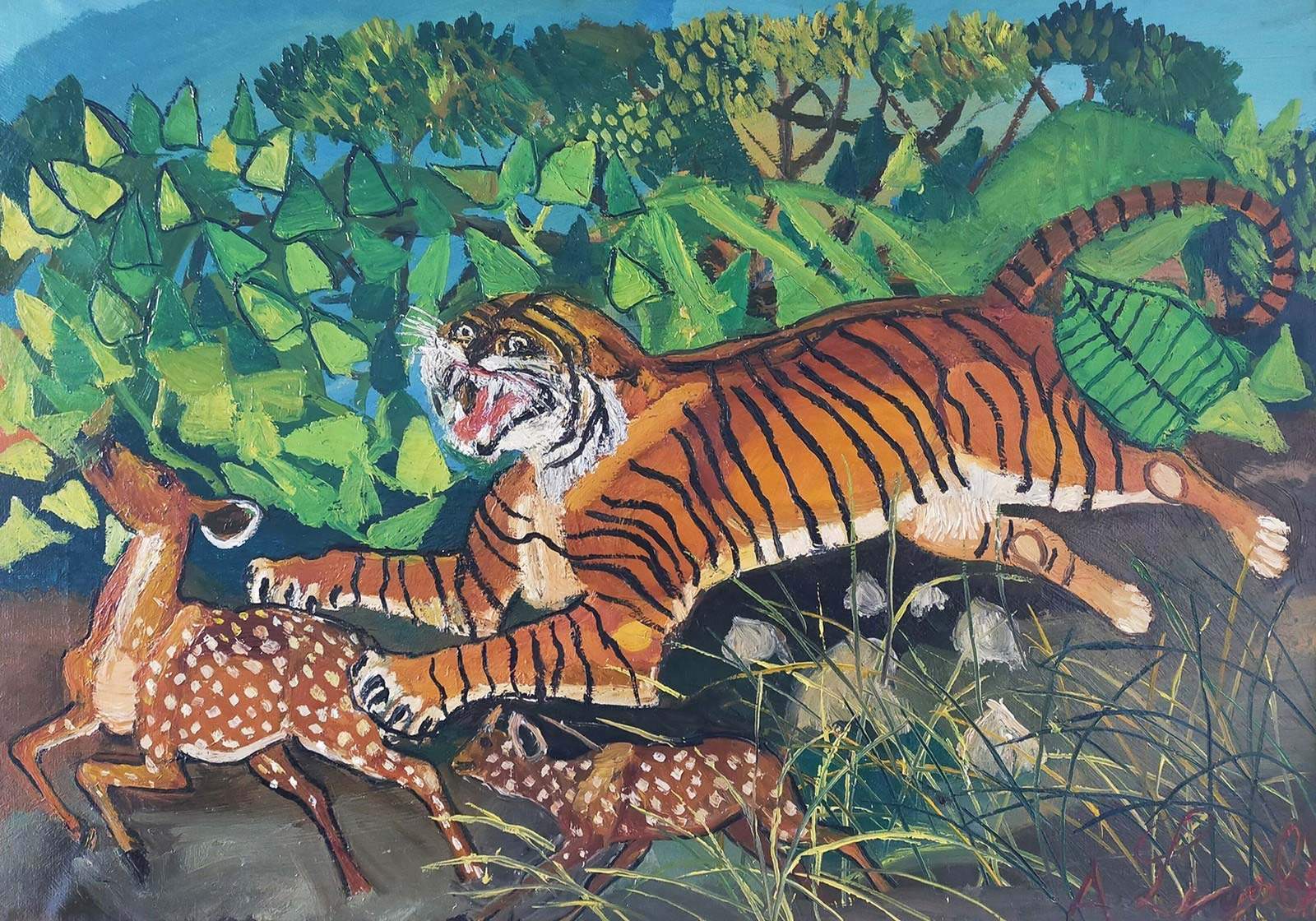

Ligabue is other than Symbolism, Realism, other “isms” (tigers in the Reggio Emilia countryside? Giammai!). And then that insistent way of sketching animals, with full-bodied brushstrokes in bright colors, that insistence on details, that irrepressible desire to get inside the bodies of foxes, eagles, cheetahs and snakes (too descriptive for many). It is the museums, particularly the international ones, that wax the success and consign it to posterity, displaying the best that has been created. I move, then, to another dimension and critical identity.

If one visits the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, one is struck, among others, by a painting by Henri Rousseau (Laval, 1844 - Paris, 1910), remembered as “the customs officer”: the painting, in its 1894 version, is titled The War, and it is an allegorical and very powerful picture. This is not the place to describe the assonances with other painters, which have been and are, still, the subject of study (Gericault, Hodler, for example). This painting was not understood at first, although artists such as Picasso and literati such as Apollinaire were able to grasp its originality immediately. In the cultural milieu of Fauvism and, at the same time, Symbolism, Rousseau astonished with its swaggering originality. Too much of everything in that painting: improbable, surreal postures and perspectives, figures deformed, or, rather, dissimilar, from the most basic norms of painting. A painting very different from what was seen at the time: I say this with great admiration, not because that time was lazy, far from it, but because this diversity strikes me. In the work, a young woman in a tattered white dress and shaggy hair, riding a black horse, with an almost mocking grimace, seems to fly over the corpses of slain soldiers, while some crows are intent on eating their remains. The landscape in the background has the power to emphasize the scene, to underscore its drama. Trees with dry branches, pink clouds.

What, then, does Rousseau have to do with Ligabue? Well, of course, Rousseau’s good fortune is to be French, and therefore to be valued and supported by the well-known French pride. Ligabue is Swiss, but then returns to his roots in the Emilian countryside. It is also true that sometimes, for convenience, very different artists, including Impressionists, are grouped together in the same movement. But that is another story.

So who is Ligabue? Is there a naïf movement? No, naïf is “only” an adjective. I insist on the meaning of naïf, which is like saying “childish,” “unnecessarily detailed,” the result of the work of “a madman,” a misfit, an unhappy person, one who goes in and out of mental hospitals. And this is the illustration of the cursed painter. Rousseau is self-taught, a stubborn winning warrior, so much so that he is in international museums. Ligabue is self-taught, practically brilliant, but he is not in the National Gallery or MoMA. The artist lives until the 1960s, and it is “inexcusable” (according to some) that he was not part of the avant-garde movements of the time (since, even, after World War II), that he did not embrace the Informal Movement, nor Minimalism, nor Concrete Art, nor Visual Poetry, all, let it be clear, very important moments in the idea of innovative creativity. Ligabue, for many, remains simply a minor, one who moves nothing in art history.

Yet his appeal has an international character, his painting is profoundly Nordic, in that awkward rigidity that has nothing sentimental, nothing endearing about it. It is expressionist, rough and rugged, not at all provincial, not at all naive. His self-portraits “pierce the screen,” as one might say about film and television, and if it were taught in schools, with far more careful reading than in the past, it would change the point of view, the gaze.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.