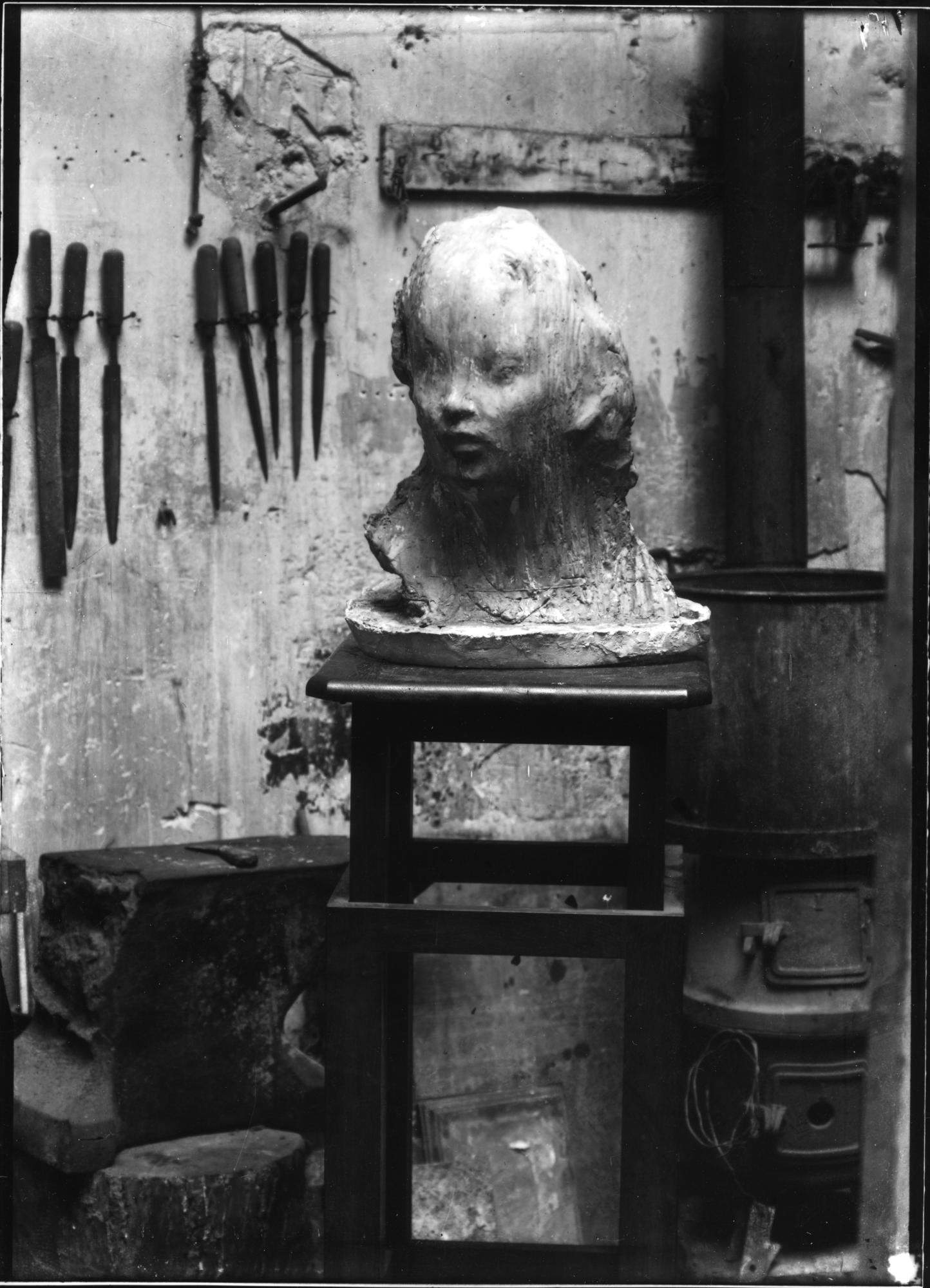

Impression d’enfant, Enfant anglais, Portrait de l’enfant Alfred Mond, Enfant de Nazareth: these are many of the titles by whichEcce Puer, perhaps Medardo Rosso ’s (Turin, 1858 - Milan, 1928) best-known masterpiece, is known. This is thelast original work by the Turin sculptor: following this sculpture, Rosso would end his career by executing variants of earlier works, and devoting himself to photography. We do not know in detail the origins ofEcce Puer, which could, however, be between February and October 1906: the artist was in London at the time, and he seems to have been commissioned by the German industrialist and collector Emile Mond and his wife Angela, who had long since moved to England, to execute a portrait of their son Alfred William, born in 1901.

The birth ofEcce Puer has since taken on legendary overtones, at least since the account of Ardengo Soffici in his 1929 monograph on Medardo Rosso, who invests the creation of Medardo Rosso’s masterpiece with almost mystical contours, believing it to be the result of an illumination that the artist is said to have had after several days of vain agonizing: “Not seeing reflected in it the character and the face of the original, [Rosso] had thrown it up and rebuilt it then, as it still did not satisfy him, redestroyed and undone. Thus had begun that terrible struggle between matter and creative imagination, which every artist knows and which has as its outcome either mortal discouragement or masterpiece. For more than a week Rosso had been standing in such a manner, trammeling about with his clay, neither seeing nor understanding anything more of what he was doing, despondent, and almost despairing of ever succeeding at anything more presentable, when one morning the child, who was blond and handsome, entered the room, a wave of light that was not that of other days invaded him, and Rosso saw him as he had never seen him before: he sees him, in his poetic and expressive reality. There he is! Here is the child Rosso was looking for. It was a moment: but it was enough for the artist to feel confident in himself and in the success of the work. Having made the child stay in that very place, Rosso, without wasting a minute, threw himself on the clay with creative fury: he kneaded, deformed, transformed, molded, raped, caressed, worked like a beast, almost as if in a dream; and a few hours later the stupendous work was finished.” The portrait would later be rejected by Alfred William’s parents because of its poor likeness, as Medardo Rosso himself would later recount (“I was to paint a portrait of a child. It came to my room; a thought told me: voilà la vision de purité dans un monde banal, and I could do nothing but give the idea of purity. The parents later said it was not resembling!”). Even, the couple refused to pay the artist his fee. Yet despite the outrage of the patrons, one of the masterpieces of modern sculpture had been born in 1906 London, and the value ofEcce Puer was not slow to be recognized by critics.

Medardo

MedardoOf course, Ardengo Soffici’s account serves to enhance the myth of the artist who saw his works appear in a flash, in a moment of lightning inspiration, even at the mere passing of a ray of light on an object or a person, as we read in the anecdote. And indeed theEcce Puer presents itself as an apparition, as the image of a figure who at one moment is present and soon after is no longer there, as the portrait of a child who truly reveals himself in a luminous epiphany. Never before had works in sculpture been seen like those of Medardo Rosso, who can be identified as the first sculptor in history to model guided by the force, even emotional, of light. And he was able to do so thanks to his stay in Paris, where he arrived in 1889, immediately taking an interest in the innovations of the Impressionists, so much so that critics have often seen him as the founder of Impressionist sculpture, although his art could not be given without the contribution of the naturalism on which he already had meditated on at the time when he resided in Milan before moving to France, as well as without the contribution of symbolism, especially at the time when his works also seek to capture an emotional afflatus, to convey a state of mind. Here, then, Ecce Puer itself becomes a work that vibrates “as if it had a beating heart,” to use an effective expression of the artist Giovanni Anselmo.

In the portrait of Medardo Rosso, little Alfred William appears to us as he emerges from the material, with his physical features barely hinted at, and with his face blurring into the lines of a curtain, offering the viewer the sensation of rapid movement, in which the child reveals and hides at the same time, in a mixture of curiosity and reluctance: according to legend, Medardo Rosso was in fact seized with inspiration upon seeing the child leaning out from a curtain precisely to eavesdrop on a conversation between his parents and some guests who had gone to their house for dinner. This sculpture, meanwhile, is one of the most shining examples of the way the artist conceived of his figures, which were never isolated, but part of the same space, devoid of boundaries. “When I make a portrait,” he would say, “I cannot limit it to the lines of the head because this head belongs to a body, it is in an environment that exerts an influence on it, it is part of a whole that I cannot suppress.” Light becomes the element that enhances the subject’s participation in the space around him, “Light is the very essence of our existence, a work of art that does not deal with light has no reason to exist. Without light it lacks unity and spaciousness, it is reduced to being insignificant, of no value, misconceived, based necessarily on matter. Nothing in this world can detach itself from its surroundings, and our vision-or impression, if you prefer the term-can only be the result of the mutual relations or values given by light, and one must catch the dominant hue with a glance.” Thus, inEcce Puer, light becomes the medium through which the surface enveloping the child eventually reveals his expression.

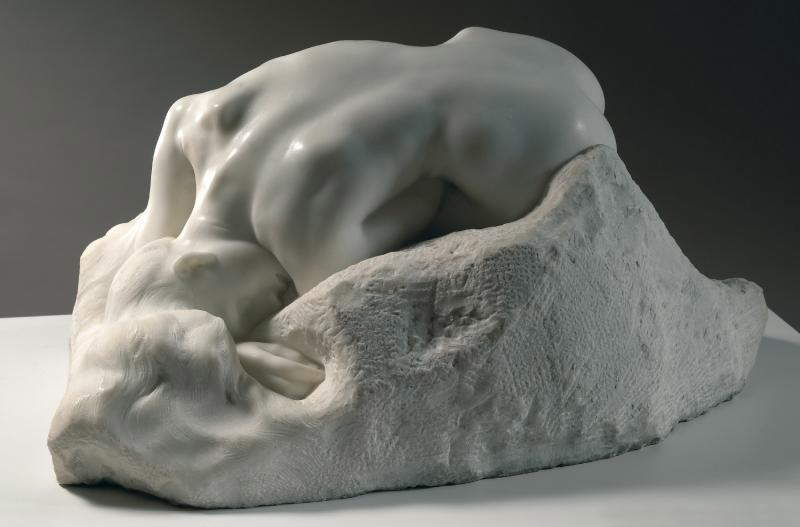

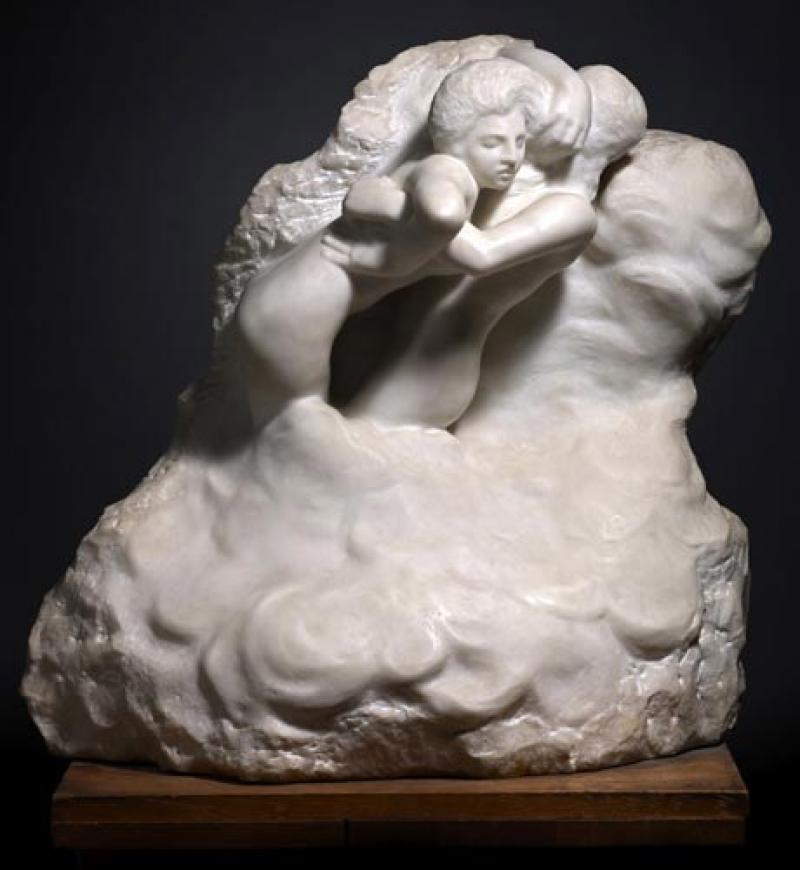

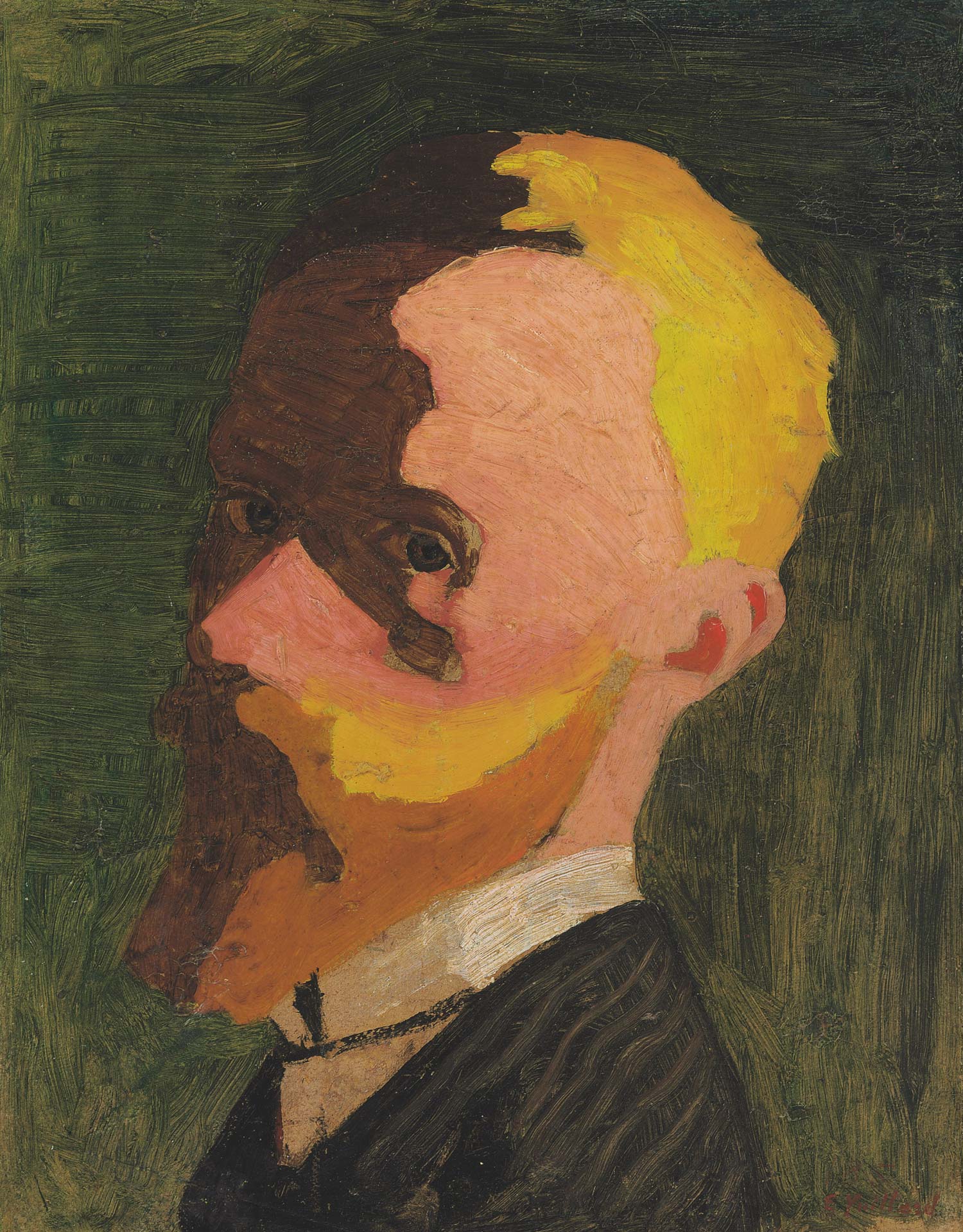

In envisioning his Ecce Puer, Medardo Rosso then had to reflect at length as much on the art of Auguste Rodin, whom he knew very well, as, in all likelihood, on the art of the Nabis: he would have looked to the former above all for his way of representing bodies in space, with the figures emerging bursting out of the formless space that surrounds them and in which they themselves sometimes blend in, whereas in the Nabis (and particularly in the art ofÉdouard Vuillard and in that of Pierre Bonnard) he would find the right balance between the role accorded to the perception of the moment (and thus between the exquisitely Impressionist matrix component) and the idea of conveying an emotion, a state of mind. One could cite as an example Rodin’s portraits, his famous Danaide, or Vuillard’s self-portrait in which the painter depicts himself in a non-descriptive manner and with unnatural colors, animated by the intention of rather communicating his feelings before nature. These were, for those times, extremely innovative researches.

It is then necessary to dwell on the famous title, with religious connotations, that Medardo Rosso may have chosen for his work in order to emphasize its apparitional character, but his intent may also have been to highlight its metaphysical character. The great scholar Luciano Caramel has written thatEcce Puer seems to refer us “to the extrasensible field of the Idea and the Spirit,” and that Medardo Rosso’s last sculpture is the one “least traceable to intentionality of objective registration, despite the fact that it must be a portrait, which one would like to be born of the impression drawn from a sudden fleeting apparition of the subject.” Medardo Rosso himself, for that matter, had defined his sculpture as a vision de pureté: one could therefore defineEcce Puer as a work in which the visible is reduced to a minimum and the form is closer to the idea than to the material. It is well known that critics, despite the late fortune of Medardo Rosso, whose role as a profound innovator struggled to be recognized for a long time (partly because, an Italian in Paris, he struggled to establish himself, and partly because even in Italy he was essentially an isolated artist), have devoted much attention toEcce Puer. Paola Mola, for example, has, like others, insisted on the dialogue between form and matter that develops in the work of Medardo Rosso, who withEcce Puer, in his search for the “ghost of form,” gives rise to a “direct encounter with the image, which comes forward and presses from within the form.” For Francesco Stocchi, the work “undoubtedly constitutes one of the points of arrival in Rosso’s complex cultural formation: naturalist, impressionist, symbolist,” with the characters underlying his sculpture nevertheless mingling in an unprecedented way, laying the foundations for 20th-century sculpture.

The extreme modernity ofEcce Puer is one of the qualities that, moreover, best help define Medardo Rosso’s masterpiece. For Rosalind Krauss, it is precisely in the simultaneous manifestation of different impressions and expressions that the most innovative features of Medardo Rosso’s work must be found: in the brief instant in which the child appears, the sculptor understands "what the ambivalence of feelings resembles. With Ecce Puer Rosso expresses both this knowledge and the very act in which it crystallizes [...]. Ecce Puer is nothing else, beginning and end, than this surface-there is nothing beyond." Max Kozloff, on the other hand, proposed a parallel with Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetry: “The hollow, cream-colored wax has a Mallarmean impact that anesthetizes the tactile sense and vibrates more as a perception of emotion than as an object that exists and has a weight and substance separate from its own body. It holds at a distance, and freezes the moment before it is possible to return to earthly existence [...] just thinking about this work, let alone therefore experiencing it, is like a kind of hypnosis.” More recent positions, however, include that of American art historian Sharon Hecker, according to whom the modernity ofEcce Puer is to be found in the various ways in which Medardo Rosso “destabilizes the continuity between image and idea, between subject and form.” Indeed, it was not the first time that the artist had reached similarly dense results of abstraction: it will suffice, therefore, to recall the tender Aetas aurea, a portrait of his wife and son dating from 1886, or even more so Madame X from 1896. WithEcce Puer, however, the artist manages to create an even more elusive, deliberately unresolved work. “Although Medardo Rosso speaks of a desire to dematerialize sculpture,” Hecker wrote, "the surface ofEcce Puer is finely wrought and surprising in its materiality." A materiality that has led the scholar to avoid overly spiritualizing or metaphorical interpretations, but that has not prevented many, especially artists (she herself cites Tony Cragg and Giuseppe Penone), from believing that the particular workmanship of this sculpture could be Medardo Rosso’s way of transforming the skin into an element that lies somewhere between the child’s outward appearance and his soul. One could speak, then, of a work that surprises and initiates the 20th century because it manages to merge all these elements: body and soul, form and matter, space and figure, absence and presence. No other work by Medardo Rosso had succeeded as well.

![Medardo Rosso, Aurea Aetas (1886 [1904-1908]; cera su gesso, 45 x 45 x 34 cm; Torino, GAM - Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) Medardo Rosso, Aurea Aetas (1886 [1904-1908]; cera su gesso, 45 x 45 x 34 cm; Torino, GAM - Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2023/2220/medardo-rosso-aurea-aetas-gam.jpg) Medardo

Medardo

Several redactions are known of the work, although the original model, in patinated plaster, is preserved at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan, with the label “1011” from an old inventory. The work was first exhibited in the same year it was made, 1906, at the Salon d’Automne in Paris and then at the Eugene Cremetti Gallery in London, under the title Portrait de l’enfant Mond: impression, after which, at the Impressionism exhibition held in Florence in 1910, it already appeared under the title Ecce Puer. Specimens of the work are held at several museums: wax on plaster examples are at the Ricci Oddi Gallery in Piacenza, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, and the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome. One in painted plaster is at the Medardo Rosso Museum in Barzio, another also in plaster is at the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh, while bronze specimens are kept at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Museum Moderner Kunst in Vienna and the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne. A bronze reproduction is also placed on the artist’s tomb at the Monumental Cemetery in Milan.

Significant was the influence that Medardo Rosso would be able to exert on many twentieth-century artists (Hecker cites Umberto Boccioni, Henry Moore, Constantin BrâncuÅŸi, Alberto Giacometti), and a work such as Ecce Puer is crucial to understanding why we can consider Rosso himself as the first modern artist. Giovanni Papini understood this well: “No one, today, dares to deny that Rosso’s art means a beginning and not already a continuation. Rosso is the first who breaks and interrupts that millenary tradition that goes from the Egyptian statuary to the verist painters of the nineteenth century: the first who makes sculpture into an art that to some no longer seems like sculpture because it crosses what seem to be the natural and unchangeable characters of sculpture.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.