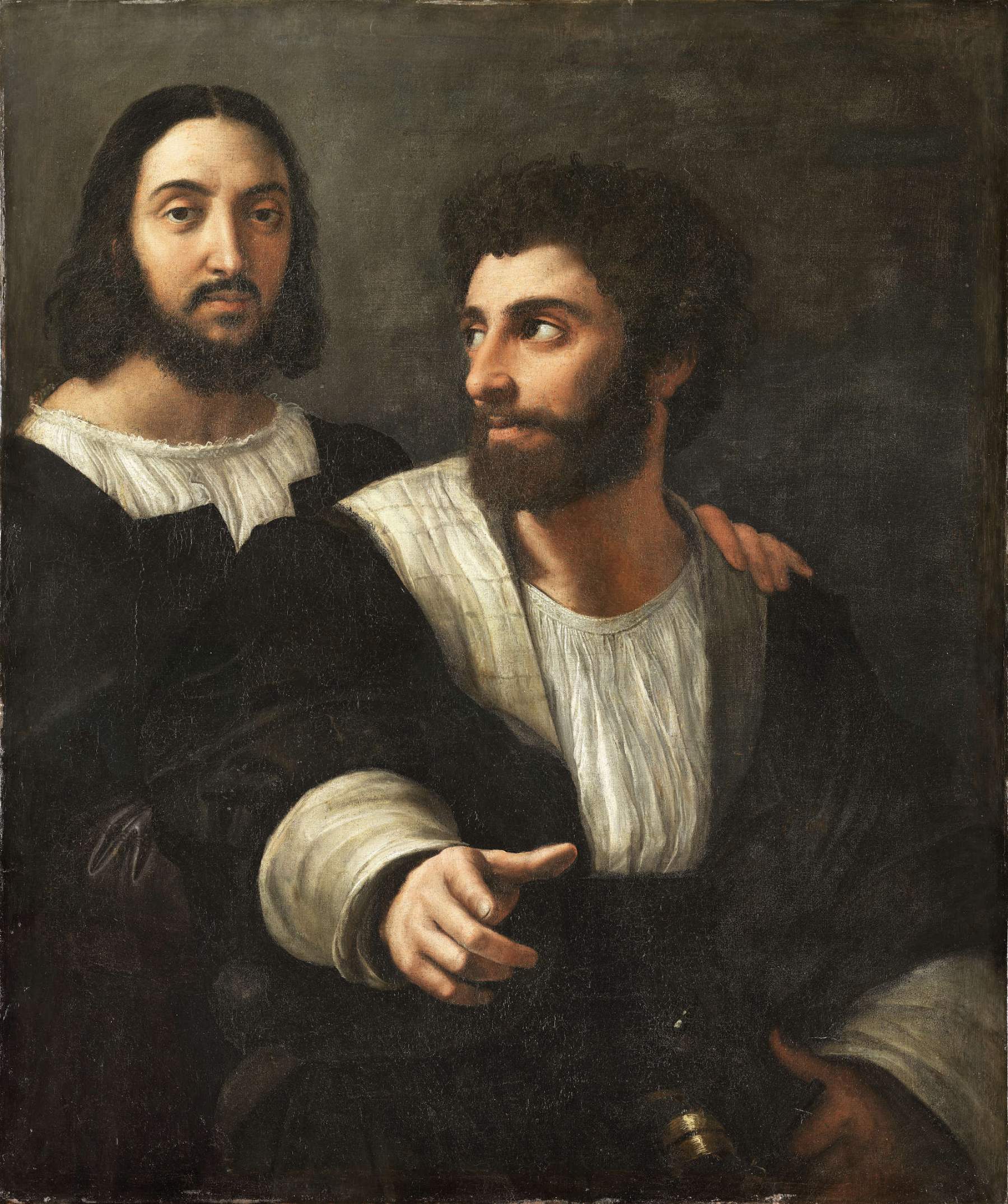

The identity of the young man seated in the foreground of Raphael’s painting, known as Self-Portrait with Friend or Double Portrait, kept at the Musée du Louvre where it entered in 1792, has remained shrouded in mystery until now1. The scene depicts an action as it is being performed: the friend, either seated or of short stature, turns his gaze toward Raphael, while the latter rests one hand on his shoulder and the other on his hip.

Despite the beauty of theSelf-Portrait with Friend and the numerous studies devoted to it over time, it still remains difficult to understand the deeper meaning of the image and to recognize, therefore, not only the character on the right, but also a third hypothetical interlocutor toward whom the young man himself points his finger out of the frame. The first reliable information about the work, never mentioned by Vasari, comes from France and is based on the inventory compiled by Rascas de Bagarris, who first, in the early 17th century, listed the double portrait among those in Fontainebleau, ascribing it to Pordenone2. In 1625 Cassiano del Pozzo confirmed its presence in the Gallery of Paintings of Fontainebleau, this time assigning it to Pontormo3.

In the Le Brun Inventory of 1683 it is attributed to Raphael for the first time. There it is referred to as Portrait of the Artist with a Friend, in which the friend was identified as Pontormo4. Since 1983, the painting has finally been accepted by almost all scholars as an autograph work by Raphael and included in the catalog of the CollectionsFrançaises5.

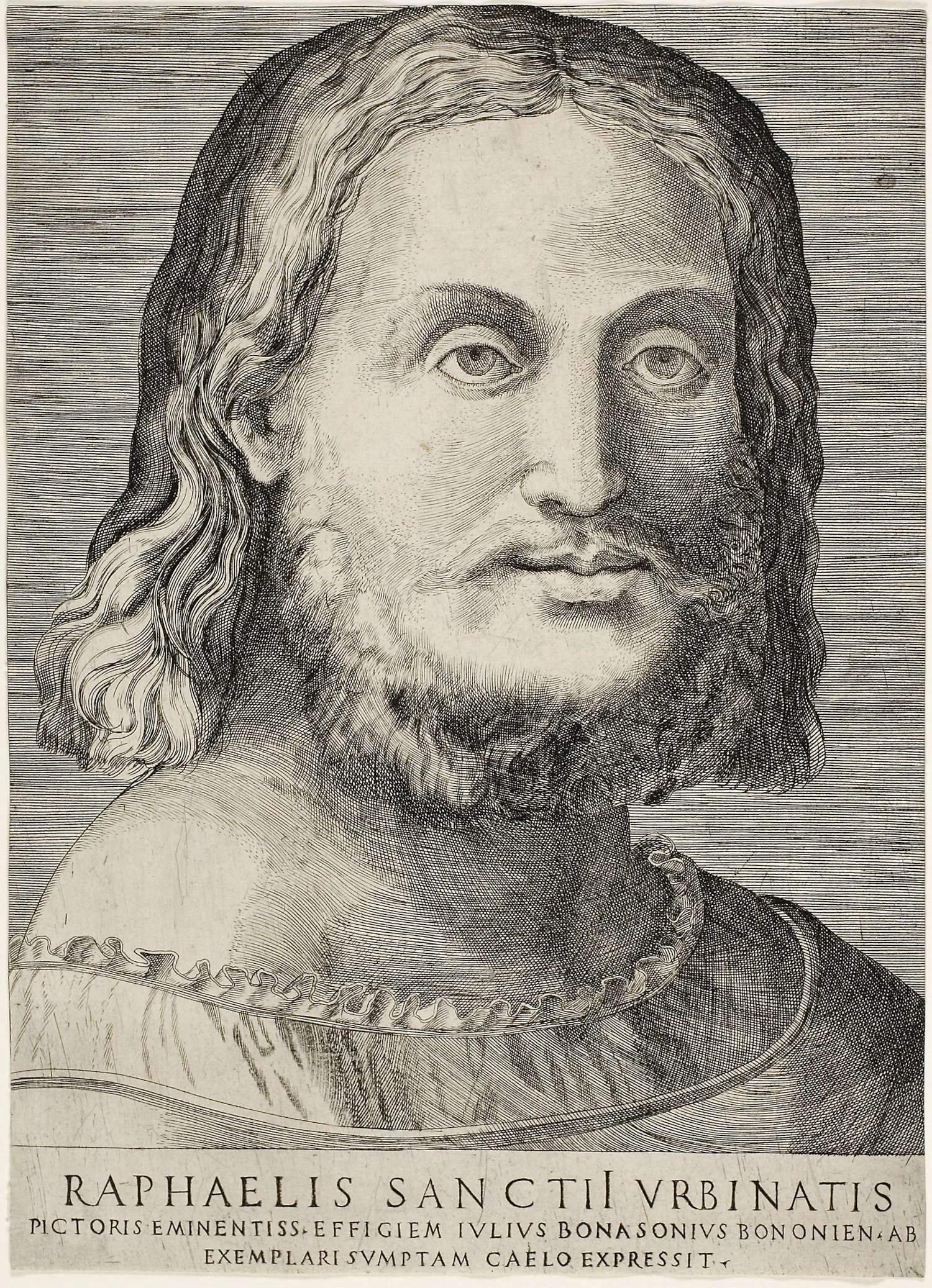

As for the identification of the two characters depicted, the person in the background has been recognized in Raphael already in the Le Brun Inventory6. Indeed, his facial features show many similarities with the self-portraits in the Uffizi and the Vatican Stanze, although these had been painted a few years earlier, when the Urbinate had not yet grown a beard and mustache. Other similarities have been shown in comparisons with Giulio Bonasone’s Portrait of Raphael (Bologna, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Pinacoteca Nazionale) and the medallion with the Portrait of Raphael on one of the ceilings of the Villa Lante in Rome, both derived from theSelf-Portrait withFriend7. François-Bernard Lépicié, in his catalog of the royal collection compiled in 1752, first refuted the identification of the friend as Pontormo and introduced that of "master of arms, " focusing on the sword for his identification8.

Over time, the names of Pinturicchio, Castiglione, Peruzzi, Polidoro, and Giovan Francesco Penni have also been proposed for the friend. John Shearman suggested Giovanni Battista Branconio dell’Aquila, one of Raphael’s executors, for whom the latter had designed the palazzo in Borgo a Roma9. The hypothesis, soon retracted by the author himself, did not, however, take into account the age difference between Raphael and Branconio, who, being ten years older than him, could not appear so young.

Cecil Gould believed he recognized the young Pietro Aretino, who had stayed in Rome with Agostino Chigi from 151710. Despite a certain similarity with the face in Marcantonio Raimondi’s Portrait of Pietro Aretino (Pavia, Civic Museums), however, Enrico Parlato has refuted the hypothesis, particularly because the sword at that time could not be used as an element of social recognition of the man of letters11. Norberto Gramaccini focused on the relationship between the master - Raphael - and the disciple without being interested in the identity of the young man but rather in the bond between the two. According to the scholar, the painting places the viewer in front of the scene of handing over the baton from the master to the pupil12. Paul Joannides and Tom Henry, on the other hand, proposed the identification of the friend with Giulio Romano13. Their theory has also been rejected by Enrico Parlato, according to whom the presence of the sword and, in general, the clothing are not consistent with the social status of the man who “was then one of Raphael’s servants. ”14 According to Parlato, moreover, Giulio’s slightly hooked nose, eye shape and thin lips, as also visible in Titian’s Portrait of Giulio Romano (Mantua, Museo Civico di Palazzo Te) do not coincide with his friend’s features.

Hannah Baader, without proposing names, has focused on the confidential and, at the same time, hierarchical relationship between the two, arguing that the painter personifies an educated individual, while his companion someone who gains understanding through questioning. According to the scholar, the gesture of the young man turning sharply toward Raphael would be provoked by his astonishment at seeing the viewer in front of them.15 Joanna Woods-Marsden, after examining theSelf-Portrait with Friend in the context of Renaissance self-portraits, based her theory on the assumption that the different height of the two figures depends on their social position. Referring to sovereigns or people of high rank, often depicted seated, and the distinguished attire of the friend in the foreground, Woods-Marsden believes that he is a man of high lineage, devoted to action, while identifying the other as a thinker.16 According to Jurg Meyer zur Capellen, the gestures of the protagonists in the double portrait reveal a certain intimacy and complicity between the two. Moreover, the friend’s finger, pointed beyond the space of the picture, is according to him directed toward a real person, a specific recipient who, although invisible, is emphatically included in the composition. He therefore speculates that the picture alludes to an act of presentation between closely related people17.

It should be remembered thatSelf-Portrait with Friend was executed between 1514 and 1520, using the oil-on-canvas technique, prepared with a gray ground composed of lead white, charcoal black, lead yellow, and ochre, applied directly to the support with a knife18. Scientific analysis (X-rays) revealed that the composition was summarily defined by a drawing, with which Raphael traced the lines of his own face, placed at a lower level than it appears now and almost at the same height as the second character. In the preparatory drawing, the head of the figure on the right appears to be turned slightly toward the painter and with its eyes oriented to the left. In the final stage of the painting, Urbinate moved his image higher than in the drawing and slightly changed the position of his friend’s chin and gaze, which, this time, looks directly at the painter. Tom Henry and Paul Joannides have also speculated that Raphael’s dress may have originally had a purplish blue tone and the young man’s a green one. Both colors seem to have been almost entirely lost today, along with the hues that gave the clothes and the painting greater chromaticity.19

In light of all these studies and in an attempt to reconstruct the context in which the canvas might have been made, it seemed appropriate to make public part of my research on Lorenzo de’ Medici the younger, nephew of Pope Leo X Medici (1513-1521). Precisely in Lorenzo it is perhaps possible to identify the second protagonist of the painting and, consequently, also to propose the name of the third interlocutor, most likely the recipient of the work, who at the time had a particularly close relationship with Lorenzo the Magnificent’s nephew.

The two men are depicted almost full-length, in dark velvet suits worn over white linen shirts, in accordance with the fashion of the time, which was particularly in vogue in Venice. Both have mustaches and well-groomed beards. On the left, Raphael wears a velvet habit with a wide neckline, from which the ruffled shirt emerges. On the right, the friend wears a voluminous black saion, open at the front. The low hanging of the wide sleeves emphasizes the line of the shoulders, while the soft neckline accentuates the breadth of the chest, emphasizing the lustre of the manly torso and uncovering the front of the neck. The left hand rests on the sword, a must-have accessory for a man-at-arms of the time.

Raphael and his friend appear as two gentlemen, dressed elegantly but with restraint. As already mentioned, their pose evokes an intimate and silent conversation, made up of gestures and glances, addressed to the third interlocutor, to whom the double portrait may have been given.

According to my hypothesis, the physiognomic features of the friend are reminiscent of those of Lorenzo de’ Medici the younger, as he would later be depicted by Raphael himself in 1517 in the Justification of Leo III in the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo in the Vatican and later, in 1518, in the Portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, now in a private collection.

Lorenzo was born in Florence in 1492, the son of Alfonsina Orsini and Piero il Fatuo, eldest son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, after whom the infant was named. After his family’s exile and subsequent restoration in 1512, he had returned to Florence as the city’s first20. From then on, his interests had turned exclusively to politics in order to consolidate his family’s fortunes and power in Florence. Within a few years, encouraged by his mother, the young man had made clear his desire to claim wider glories and honors, including the conquest of new territories, in the explicit hope of becoming the undisputed head of Florence, a city then devoted to France21.

According to available sources, Lorenzo was short in stature but with a handsome face; he had brown hair, a white complexion, and bore a striking resemblance to his mother. He enjoyed good health and had a toned and agile body22. In the Portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, perhaps a gift to be sent to France to the Medici’s betrothed, Madeleine de la Tour, the color of the eyes and hair appears lighter than in theSelf-Portrait with Friend. This, however, may be due to the fact that the Portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino had been repainted in several parts, including the face, which was cut off at the bottom and sides, as X-ray analysis revealed23. Fortunately, the Uffizi Galleries still preserve copies of the portrait, executed by Alessandro Fei and Cristofano dell’Altissimo in the 16th century, almost certainly before the repainting. The canvases could thus support the hypothesis that Lorenzo’s eyes and hair were actually darker-exactly as they appear in theSelf-Portrait with Friend.

When compared, the three portraits of the Medici painted by Raphael seem to share some common features in the face: the low forehead; the width of the space between the eyebrows and the shape of the eyebrows themselves; the large eyes; the pronounced nose; the full, sensuous lips; the curly hair; the neatly trimmed mustache and beard; and the long, strong neck. In the Justification of Leo III, in the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo in the Vatican, Lorenzo is depicted at the top right. He is standing and elegantly dressed. One hand is on his chest, while the other rests on his hip, just as in the Portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, which additionally shows the stocco hidden under his overcoat. This pose, so blatant in all three paintings, clearly evokes a strong leadership role held by the young man. In theself-portrait with friend in the Louvre, Lorenzo had not yet been proclaimed duke of Urbino, and perhaps for this reason his attire appears less lofty than in the other two paintings, although the sword seems to be the constant attribute that determines his social status.

Another comparison can be made with the profile of Lorenzo found on Francesco da Sangallo’s bronze medal, preserved in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. In this depiction, the head is turned to the right, in a classical pose. However, the pronounced nose, large eyes, hair style, and beard appear similar to those in the double portrait.

Considering the fact that Raphael and Lorenzo had known each other for some time, thanks mainly to the intermediation of Leo X, the question remains as to who the third interlocutor might be to whom the young Medici seems to turn with great spontaneity.

Was he perhaps a very important man, so much so that he could not be depicted with the other two, who were of lower rank? Given the role Lorenzo played, it is possible to speculate that the person of higher lineage than his might have been a king and, perhaps, Francis I of France, with whom he had recently formed a strong bond. The two young men had in fact met through correspondence produced by the work of ambassadors and officials of the two courts following the coronation of Francis I at Reims on January 25, 1515. The sovereign, who was then twenty-one years old, and Lorenzo, who was twenty-three, had immediately hit it off, to the point that the latter, faced with the monarch’s desire to descend to Italy shortly to regain the duchy of Milan, had been willing to enter into negotiations in support of his military campaign and eventually even to submit to his wishes.24 For this reason, on May 24, 1515, Lorenzo had had himself elected captain general of the Florentine troops by the Bailiwick of Florence25. Shortly thereafter, the pontiff had appointed him as ambassador of the Signoria to the King of France and supreme captain of the papal militia, replacing his uncle Giuliano de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours, who had fallen ill in the meantime.

The understanding between Francis I and Lorenzo had been consolidated at a time when the Medici’s papal and Florentine militias, encamped in the Po Valley, had remained inoperative, allowing his majesty to approach Milan and fight at Marignano, with the support of the Venetian army, against the Swiss mercenaries of Duke Maximilian Sforza. The resounding victory achieved on September 14, 1515, by the king, who had fought in person in the bloody battle, later known as the Battle of the Giants, had cemented the relationship between the two young potentates, who had since begun to see each other regularly in Milan.26 Medici had stayed in the Lombard city until at least November 21, the day he left for Rome, before moving to Florence on the 30th to attend the solemn entry of Leo X into the city. He had then returned to Reggio where he had met again with the king, in whose retinue he had entered Bologna on December 11 to take part in the famous meeting between the pope and Francis I27. After the Bologna consultations, Lorenzo had again followed the sovereign to Milan, a city in which they had often shown up together, at least in the early months of 1516.

Where was Raphael during these months of intense diplomatic activity? And especially before that? By November he was absent from Rome. As already hypothesized by Francesco Paolo Di Teodoro and Vincenzo Farinella, it is likely that he had gone first to Florence, to participate in the pontiff’s triumphal entry and settle the question of the facade of the Basilica of San Lorenzo and, then, to Bologna, following Leo X and his court.28 If so, it is presumable that, by virtue of the prestigious posts at the holy see and the esteem he enjoyed in some Italian courts including that of his Urbino, Raphael could have participated in a private meeting with the king in Bologna, perhaps to complete a diplomatic mission on behalf of the Medici. Nor, perhaps, should the hypothesis be entirely discarded that the three may have had the opportunity to discuss the question of Urbino, over which the pope had expressed his intention to oust the duke and put Lorenzo himself in his place, with the help of France.

In theSelf-Portrait with Friend, Raphael may thus have depicted himself as a model of political wisdom meeting the king, along with the Medici, to show him his willingness to fully support the young man. Both the gesture of clasping and reassuring his friend and the firm gaze directed at the third interlocutor seem to express determination and a strength of persuasion appropriate to such a role. Raphael - adept at narrating the politics of the time in his paintings - was, after all, the official artist of Leo X, the one to whom he had assigned the most prestigious commissions of his papacy. Indeed, the Urbinate was working not only in the St. Peter’s building site but also in the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo, the only one in the papal apartment for which he had designed a pictorial cycle alluding to his politics.

It may also be plausible that the Bologna consultations may have provided Raphael with an opportunity to showcase his qualities to the monarch, who had a reputation for greatly appreciating contemporary painting. Incidentally, the celebrations that had taken place in parallel with the diplomatic meetings had been attended by some of the leading musicians and artists of the time, such as Leonardo da Vinci. Moreover, thanks to the mediation of Florimond Robertet, personal secretary and treasurer of Francis I-with whom Lorenzo was always in close contact-Raphael might also have had the opportunity to offer himself to the French sovereign as a consultant in antiquarian matters. During the Bologna meetings, in fact, the king had expressed interest in ancient statuary and officially asked the pope for a gift of the famous Laocoon sculpture, which had been found in Rome a few years earlier.29 Raphael may then have been involved in particular because of the new position assigned to him at the end of August 1515 by Leo X, who had appointed him prefect of the excavations in Rome, with the right to be the first to view all the unearthed material containing ancient inscriptions.

This would explain the informal attire of the two men, which seems to correspond to that suggested in the Book of the Courtier by Baldassarre Castiglione, who, among other things, had written a long prologue to the text in the fall of 1515 in which he praised Francis I, stating that it would be a grave error for the Florentines not to obey him.30 According to Castiglione’s prescriptions, the courtiers were to wear comfortable black or dark clothes, avoiding eccentric or fashionable attire and maintaining, rather, an Italian style, corresponding to their inner identity31. It should also not be forgotten that Castiglione had participated in the Bolognese consultations as a diplomat to plead before the king the cause of his lord, Francesco Maria della Rovere, duke of Urbino, who was threatened by the pontiff with excommunication and confiscation of his state and property.

Moreover, Castiglione had included Raphael, with whom he had a fraternal friendship, among the protagonists in the manuscript copy of the book, compiled by an amanuensis around 1514-1515 under his close supervision.32 In such a case, it is possible to ventilate the idea that Raphael himself may have brought with him to Florence or Bologna the canvas on which to make theSelf-Portrait with Friend and painted it entirely-or in part-on the spot, or, alternatively, handed it over to the young Medici after he had finished it. We can also imagine that, even if Raphael had not been able to meet the king together with Lorenzo, his presentation would still have reached Francis I through the portrait, which, in any case, on one of these two occasions may have entered the royal collections in France, which were later transferred to the Louvre.

This contribution was originally published in No. 16 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper. Click here to subscribe.

1 In view of the vastness of the bibliography on Raphael and the history of theSelf-Portrait with Friend and its attributions, a summary is provided here: L. Dussler, Raphael. A Critical Catalogue of his Pictures, Wall-Paintings and Tapestries, London - New York 1971, p. 47; S. Béguin, Raphaël et un ami, in Raphaël dans les Collections Françaises, exhibition catalog (Paris, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, November 15, 1983 - February 13, 1984), Paris 1983, pp. 101-104; J. Shearman, Double Portrait of Raphael, in Raphael the Architect, exhibition catalog (Rome, Palazzo dei Conservatori, February 29-May 15, 1984) edited by C. L. Frommel, S. Ray, M. Tafuri, Milan 1984, p. 107; J. Cox-Rearick, The collection of Francis I: Royal Treasures, Antwerp 1995, pp. 198, 217-222 and p. 406; J. Meyer zur Capellen, Raphael. A Critical Catalogue of his Paintings, vol. 3: The Roman Portraits, ca. 1508-1520, Landshut 2008, pp. 23-24 and pp. 136-143; T. Henry, P. Joannides, Self-Portrait with Giulio Romano, in Late Raphael, exhibition catalog (Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, June 12-September 16, 2012 and Paris, Musée du Louvre, October 8, 2012-January 14, 2013), edited by T. Henry, P. Joannides, Madrid 2012, pp. 296-300; E. Parlato, Self-Portrait with Friend, in Raphael 1520-1483, exhibition catalog (Rome, Scuderie del Quirinale, March 5-June 2, 2020), edited by M. Faietti, M. Lanfranconi, F. P. Di Teodoro, V. Farinella, Rome 2020, pp. 66-67; E. Parlato, Who is Raphael Talking to? Attorno al Doppio Ritratto del Louvre, in Amica veritas. Studies in Art History in Honor of Claudio Strinati, edited by A. Vannugli, Rome 2020, pp. 343-352; and T. Henry, Self Portrait with Giulio Romano, in Raphael, exhibition catalog (London The National Gallery, April 9-July 31, 2022), edited by D. Ekserdjjan, T. Henry, London 2022, pp. 88-89.

2 See S. de Ricci, Description raisonnee des peintures du Louvre. I. Ecoles étrangères: Italie et Espagne, Paris 1913, p. XI. The manuscript supposedly containing the inventory is by Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, ms. latin 8957, fol. 128) was first published by S. de Ricci in Revue archeologique, 35, 1899, p. 342. These are mostly drawings of ancient monuments and inscriptions from southern France. Unfortunately, however, in this manuscript I could not find the inventory.

3 C. dal Pozzo, Legatione del signore Cardinal Barberino in France, in E. Müntz, Le château de Fontainebleau en 1625, d’après le diarium du commandeur Cassiano dal Pozzo, Paris 1885, p. 269.

4 In A. Brejon de Lavergnée, L’Inventaire Le Brun de 1683: la collection des tableaux de Louis XIV, Paris 1987, p. 94.

5 Béguin, Raphaël ..., cit., pp. 101-104.

6 Brejon de Lavergnée, L’Inventaire ..., cit., p. 94.

7 Béguin, Raphaël ..., cit., p. 102.

8 F.B. Lépicié, Catalogue raisonné des tableaux du Roy, avec un abrégé de la vie des peintres, fait par ordre de Sa Majesté, vol. I, Paris 1752, pp. 96-97.

9 Shearman, Double Portrait . .., cit. p. 107.

10 C. Gould, Raphael’s Double Portrait in the Louvre: An Identification for the Second Figure, in Artibus et Historiae, 10, 1984, pp. 57-60.

11 Parlato, With whom he speaks . .., cit., p. 347.

12 N. Gramaccini, Raffael und sein Schüler. Eine gemalte Kunsttheorie, in Georges-Bloch-Jahrbuch des Kunstgeschichtlichen Seminars der Universität Zürich, 2, 1995, pp. 45-55.

13 P. Joannides, Raphael and his circle, in Paragone, 51, 30 (601), 2000, pp. 3-42 and Henry, Self Portrait..., cit., in Raphael... , cit., pp. 88-89.

14 Parlato, To Whom He Speaks . .., cit., p. 347.

15 H. Baader, Sehen, Täuschen und Erkennen. Raffaels Selbstbildnis im Louvre, in Diletto e Maraviglia. Ausdruck und Wirkung in der Kunst von der Renaissance bis zum Barock. Festschrift für Rudolf Preimesberger, Emsdetten 1998, pp. 41-59.

16 J. Woods-Marsden, Renaissance Self-Portraiture. The Visual Construction and the Social Status of the Artist, New Haven - London 1998, pp. 124-128.

17 Meyer zur Capellen, Raphael..., cit., p. 142.

18 On the technical aspect see B. Mottin, E. Ravaud, G. Bastian, M. Eveno, Raphael and his Entourage in Rome: Laboratory Study of the Works in the Musée du Louvre, in Late Raphael... , cit., p. 362.

19 Henry - Joannides, Self-Portrait with . .., cit., in Late Raphael... , cit., p. 296.

20 G. Benzoni, Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, in Encyclopedia Machiavelliana, 2014 (online edition).

21 F. Vettori, Scritti storici e politici, Bari 1972, pp. 152-153 and p. 161.

22 Idem, p. 272.

23 K. Oberhuber, Raphael and the State portrait-II: the portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici, in The Burlington Magazine, 821, 1971, pp. 439-440.

24 A. Giorgetti, Lorenzo de’ Medici captain general of the Florentine republic, in Archivio storico italiano, 11, 1883, pp. 212-213.

25 Idem, pp. 210-211.

26 M. Sanuto, I Diarii di Marino Sanudo (1496-1533), vol. 21, Venice 1887, cc. 140, 273, 284, 297, 377.

27 On the Bologna meeting see N. Rubello, Il re, il papa, la città. Francis I and Leo X in Bologna in December 1515 (doctoral dissertation, University of Ferrara), Ferrara 2012.

28 On Raphael’s absence in Rome and the assumption that he had gone to Florence and Bologna see G. Amati, Sopra due case possedute da Raffaele da Urbino, in Il Buonarroti, vol. III, Rome 1866, pp. 58-59 and F. P. Di Teodoro and V. Farinella, Santi Raffaello, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 2017 (online edition).

29 On Francis I’s request to the pontiff see Reports of the Venetian Ambassadors to the Senate edited by Eugenio Alberi, series II, vol. III, Florence 1846, p. 116.

30 P. Serassi, Letters of Count Baldessar Castiglione, vol. I, Padua 1769, p. 182.

31 B. Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, Turin 2017, pp. 158-160.

32 O. Zorzi Pugliese, The Early Extant Manuscripts of Baldassar Castiglione’s “Il libro del cortegiano” (transcriptions), 2012 (digital edition), pp. 225, 306, 377, 546, 560-561.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.