Leonardo da Vinci’s famous maxim “sad is that disciple who does not advance his master” seems to have guided the students of Giuseppe Baldini (Livorno, 1807 - 1876), a Leghorn artist who imparted the first rudiments in painting to important names in 19th-century art, among whom surely the best known are Giovanni Fattori and Vittorio Matteo Corcos, but who counts other significant names such as those of Renato Fucini, Natale Betti, and Giovanni Costa. Certainly, in this concept transpires a confidence in progress, a parable of art that evolves and does not stand still. But there is also a vein of tragedy: noting how the master ends up losing his artistic dignity, his creative autonomy, reduced almost to subordinate in a brighter career. And while it is true that we have no assurance that Baldini’s name, deprived of the link with his astonishing pupils, would have stood the test of time (indeed: it is quite likely that without that mention by right in the Factorian or Corcos biography he would perhaps have been condemned to complete anonymity), there is no doubt that a certain tendency to reduce his experience to little arises from the comparison with these giants.

Critics, from Christine Farese Sperken to Giuliano Matteucci, from Ilaria Taddei to Fernando Mazzocca, have often dismissed him with adjectives such as “modest” or “mediocre,” judgments that have become repeated formulas rather than the results of real insight. Even transcription errors in his name (“Antonio Bandini,” “Boldini”) testify to a certain carelessness in handing down his memory. But weighing more heavily than any other judgment were the memoirs of Giovanni Fattori, his most famous pupil. In late correspondence, Fattori first remembered Baldini with respect, acknowledging him as the “only artist painter” present in Livorno, but later described him with ill-concealed irony: “the only genius from Leghorn at that time who had studied in Rome without understanding anything about it, with only the conceit of being a great man, with a long beard in the manner of Leonardo, who for decency coiled it and hid it under his robe; hat in the manner of the Calabrese - ironed and large stick - proud look - and finally a ball full of wind - morality in the family not much. Only he had of good he was not interested and the first elements I took from him and attended his school for a few years without understanding anything.” Then in 1906 the tone again softens: “I had the first elements from him. I do not remember how my decision was to leave Baldini and come to Florence. I only know that I wrote a letter to this good teacher of mine, thanking him and notifying him of my decision, which he approved.”

As Vincenzo Farinella has observed, these oscillations reflect the old Fattori’s need to extricate himself from a Livorno provincialism and to construct the image of the “born” artist, devoid of masters. And yet, although Fattori’s memoirs reveal a rather modest character, both as a painter and as a teacher, the concurrence of significant names in Italian painting among his pupils cannot be a mere coincidence, which is not even justified by the fact that he was the only artist active in Leghorn at that date, since there were relatively well-known painters in the Tuscan milieu such as Carlo Chelli, Vincenzo De Bonis, and Niccola Ulacacci. After all, the goodness of a master is also, and sometimes especially, measured by the quality of his disciples. The fact that Giovanni Fattori, Corcos, Costa, Betti and others achieved not inconsiderable artistic achievements attests to the extent to which Baldini was able to transmit a method, vision and creative drive that continued to live on well beyond his personal production. It is therefore through this lineage that his legacy takes on a historical and formative value that exceeds the mere stylistic judgment on his canvases. The training offered by Baldini turns out to be decidedly far from the standards of the Romantic academies of the time, founded on studio practice and copying from the antique. As recalled by Fucini in his autobiography Leaves in the Wind, whose recollections of Baldini are decidedly more positive, the master used to take his pupils “fishing along the most remote ditches of the city”, or he would take them on visits to the studios of other artists, such as that of the sculptor Temistocle Guerrazzi, or to go for walks and baths during the warm season, along the beaches between Marzocco and Calambrone, while he himself drew drawings from their “dry and tanned nudes.” At other times he would ask them to linger and “admire the clouds of a beautiful sunset.” This sort of “free school of drawing,” as Vincenzo Farinella speculates, may have been the model from which Fattori himself drew inspiration to define his own teaching method once he obtained tenure at the Florentine Academy.

But following Baldini also meant being introduced to an ethical and political horizon. A man of ardent Mazzinian convictions, Baldini took part in Risorgimento conspiracies, as attested by police reports from 1838, which indicate him in contact with Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi and other patriots. He frequented meeting places watched by the Grand Ducal police where they discussed Italy and freedom, often in the company of his students. He was also a correspondent of Giuseppe Mazzini and was elected second captain of the civic guard, and in that role probably took part in the 1849 resistance of the Leghorn people against Austrian soldiers who wanted to restore the grand ducal power of Lorraine. The writer Francesco Ferrero remembered him as a “beautiful figure of an ardent Mazzinian.”

It is plausible that Fattori and Fucini breathed from him that civic sense and moral commitment that shines through in their works and writings. In this sense, it should be noted, as among his pupils was Pietro Pifferi from Grosseto, who came to Livorno following his uncle Paolo, parish priest in the church of San Jacopo, who fell in battle at Montanara in 1848, and is remembered as one of the martyrs of the Risorgimento. These patriotic velleities of his are also confirmed by the recollections of the poet Renato Fucini, who recalled “his beautiful sorrowful eyes when in the silence of those ditches a patrol of Austrian soldiers passed by in a boat, looking at us hard and suspicious.”

Let us now come to his activity as a painter, which, although it does not detect exceptional characters, appears more than dignified, although unfortunately rare are the news about it, and well other studies would deserve that the present article. Born in Leghorn on January 5, 1807, Baldini showed from a young age a natural talent for drawing, which led him to theAccademia di San Luca in Rome, where he studied under Tommaso Minardi, a central figure of Italian Purism. Although forced to abandon his studies because of economic difficulties, he distinguished himself in academic competitions, winning second prize in 1827 for a drawing of the Laocoon, praised by Minardi himself: “He made such rapid progress in drawing that he surpassed many and arrived among the best pupils.”

Among Baldini’s earliest known interventions, we know that around 1830 he was involved by Andrea Gambassini, a Leghorn cabinetmaker who became famous for his wooden models of a number of Italian monuments, in the creation of the pictorial part of the reproduction of St. Peter’s Basilica, a model that was widely successful, being taken on tour to Italy, France, Russia and even the United States.

Between the mid-1930s and the early 1940s, Baldini received numerous commissions for frescoes in the palaces that Livorno’s new bourgeoisie had begun to build, including those that decorated some of the rooms in the city’s most sumptuous building, commissioned by the wealthy French businessman Francesco De Larderel. For the sumptuous palace, Baldini produced paintings in the Gabinetto Gotico and frescoed the vault of the Salotto Rosso with a cycle devoted to the arts and productive sources. Ceres, Minerva and Mercury appear in an allegory of Industry, with a boraciferous dandelion in the background, a symbol of family fortune. In the Rococo drawing room, on the other hand, he painted the Allegory of Fame on the vault. The attribution of these cycles to Baldini, advanced by Maria Teresa Lazzarini, is based on documentary sources and stylistic comparisons, although it appears at least unusual for the marked neoclassical style, distant from his other known works.

But it is certainly within the Livorno temples that Baldini left the most important works of his production (although, unfortunately, several were destroyed by the war: this is the case of the frescoes he painted between 1844 and 1846 for the Armenian church of San Gregorio Illuminatore in Livorno, where Baldini created for the apse canopy the image of the Eternal Father and in the corbels of the dome the Evangelists). In all three of Livorno’s large nineteenth-century churches Baldini made a number of altarpieces and paintings. In the church of San Giuseppe between the 1840s and 1860s he produced Il martirio dei Santi Crespino e Crespiniano (The Martyrdom of Saints Crespino and Crespinianus), which before being placed on the altar appeared at the 1843 Exposition of Objects of Fine Arts of the Florentine Academy and was commented on as a “picture of effect, not without high intention in the execution of a heartfelt religious idea.” In Livorno, however, he did not reap the same success and was mocked in a local newspaper: “one of the strong athletes has already fallen slain at the foot of the air... the other is about to receive the blow from the executioner... the priest unyielding to the prayers of tender maiden, and of a weeping old man, hints at the simulacrum, as if to say: he is sacrificed, and will be saved.” Still, this is perhaps one of Baldini’s most convincing works, certainly traceable to historical romanticism veined with ethical-moral intentions, but ennobled by a great attention to a skillful use of chiaroscuro and the plastic highlighting of figures that may recall a seventeenth-century and Caravaggesque tradition filtered through nineteenth-century academic painting, which reverberates especially in the rendering of the executioner.

Despite controversy, Baldini produced two other works for the church of San Giuseppe, a canvas depicting the Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter and Jesus Praying in the Garden. While the last one turns out to be destroyed and known only through black-and-white photographs, the second one still exists despite being in miserable conservation condition. Although the work was judged positively by Cesare Venturi for the masterful skill in drawing, the “unexceptionable naturalness” of the bodies, and the composition constructed “with solidity and ingenious good taste,” it actually appears to be the weakest of those in the church in Piazza Due Giugno and, perhaps also in comparison with his other paintings preserved in Livorno churches, appears to be the result of a tired Nazarene purism, coldly static and tinged with pathetic accents. Around 1860 for the temple of Santa Maria del Soccorso, Livorno’s largest church and an authentic museum of 19th-century painting with works by Enrico Pollastrini, Giovanni Bartolena, Nicola Ulacci, and Ferdinando Folchi, Baldini created a large painting about four meters high depicting St. Peter the Apostle. The work, like the entire chapel, was commissioned by Alessandro Malenchini, gonfaloniere of Livorno between 1844 and 1846, and a leading figure in those democratic circles so dear to the painter.

This is a good proof in which the monumental figure of the saint emerges with plastic force from a dark background, enveloped in a light of its own that emphasizes its sacredness. The layout betrays a Baroque reminiscence for the luminous vibration, but is purged of any pathetic or rhetorical excess, in keeping with Baldini’s academic purism. The whole is balanced and solemn, representing the tension between Baroque memory and formal purity, a hallmark of Baldini’s sacred painting.

Also attributed to Giuseppe Baldini is a canvas depicting Don Giovanni Battista Quilici kept in the Istituto Santa Maria Maddalena in Livorno, which flanks the church of San Pietro e Paolo. It was painted a few years after the clergyman’s death, but chronicles recall how the work was criticized by Monsignor Giovanni Battista Bagalà Blasini, because he found it unassuming and not representative of Quilici’s joviality.

In 1864, commissioned by the parish priest Don Alessandro Pannocchia, Baldini made a new altarpiece, perhaps the last one destined to adorn Livorno’s churches, depicting St. Martin Bishop of Tours resurrecting a young boy, for the church of San Martino in the Salviano district, which earned Baldini 2169 liras. The work, whose merits Venturi highlighted, particularly the care with which the numerous figures were outlined and characterized, was criticized by the same author for a coloring that did not live up to the drawing so much as to appear “sluggish.” The painting seems to rework some of the figurative groups present in Enrico Pollastrini’s famous work, preserved in the church of Santa Maria del Soccorso and depicting The Miracle of the Resurrection of the Son of the Widow of Naim from 1839.

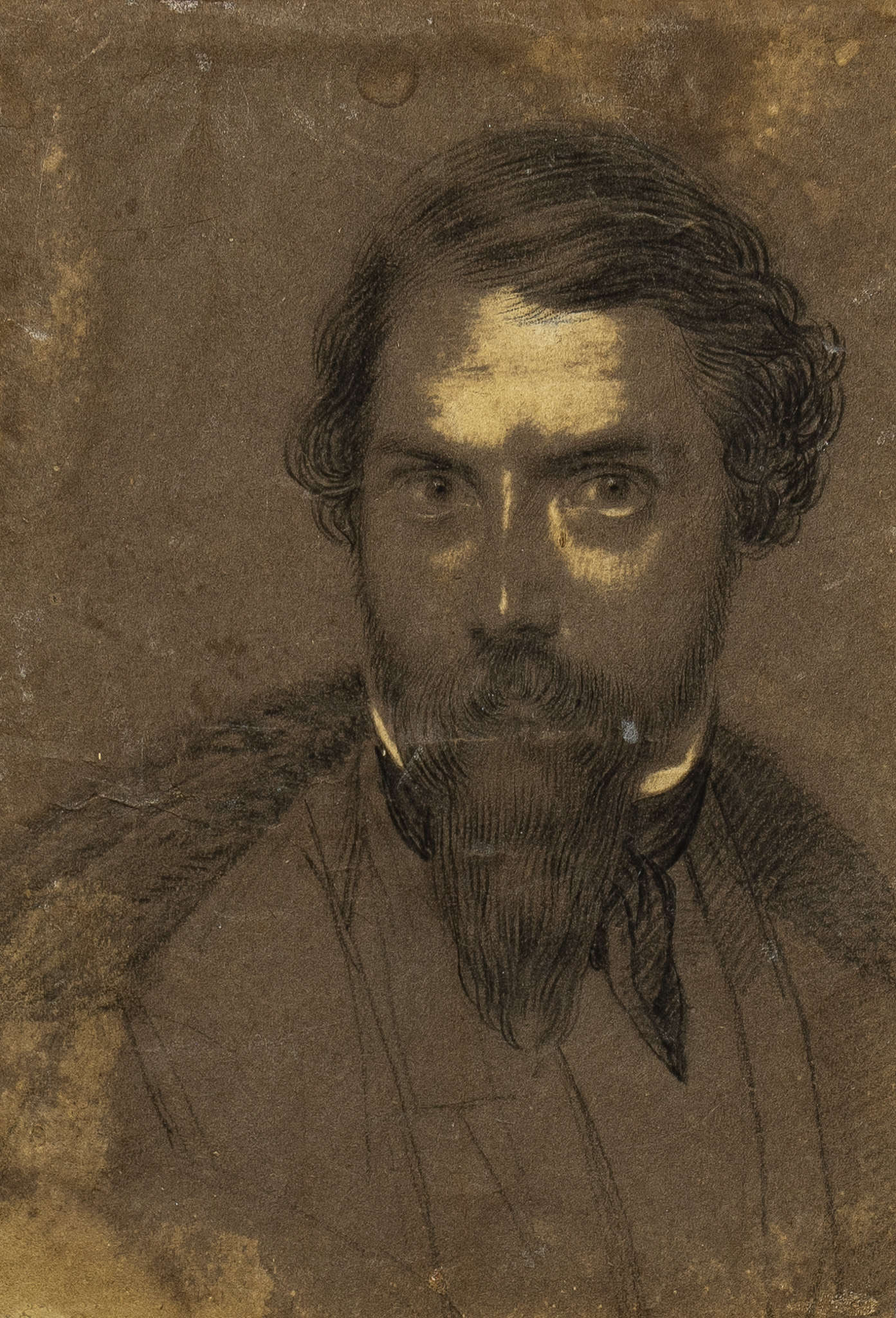

Baldini’s output, however, also counts paintings with secular themes, including two self-portraits, attributed to the painter, preserved at the Giovanni Fattori Civic Museum in Livorno. The first, now under restoration, is an oil dated between 1825 and 1835, but Vincenzo Farinella proposes a later placement around 1840. Despite its compromised state of preservation, it reveals a certain vigor in drawing, which is most evident in the second charcoal self-portrait, displayed in the Livorno exhibition Giovanni Fattori a Revolution in Painting, where the direct gaze and pose restore the image of the proud and unconventional man that the memories of his pupils pass on. Two additional paintings complete the best-known core of secular production. Portrait of a Lady, analyzed by scholar Isabella Tronconi, and theAllegory of Victory. The former is probably a fragment of a larger scene, and belongs to that dignified mid-century Leghorn bourgeois portraiture known from some of the photographs accompanying Venturi’s essay on Baldini, executed with sober elegance and measure, with some attention to the restitution of physiognomic data. Allegory of Victory, kept in the deposits of Palazzo Pitti, reveals a more idealized tone and refers back to the formal smoothness learned from the master Minardi, but with personal classicist accents.

Alongside these works, Baldini tried his hand at more intimate and spontaneous painting, largely untraceable today: portraits of his wife Baluganti, son Eugenio and some models, where the artist abandons academic idealization for a more vivid and natural rendering. In these pieces, as Farinella observed, emerges “a frankness of approach to reality” that anticipates a more modern sensibility. Completing his catalog are some landscapes, known only from reproductions, which according to Dario Durbè showed affinities with the manner of Serafino De Tivoli, and a navy that appeared at auction, closer to Romanticism than to Macchiaioli naturalism.

Finally, three small works passed on the foreign market, attributed to the Leghorn artist, reveal a lesser-known side of the painter: an interior with a woman absorbed in front of a mirror; an oil on cardboard dated 1870 titled The Artist Studio; and an interior with a male and female figure in 18th-century costume. The former shows a finely detailed scene of a bourgeois domestic setting and seems not far removed from other works already mentioned in the article. More unusual, however, are the other two works: The Artist Studio, perhaps inspired by Giovanni Boldini’s Connoisseur, appears to be a quick, sketchy study; while the last painting, which is more carefully detailed, fits into that genre of costume painting, elegant and salon-like, which enjoyed wide popularity among foreign patrons between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is likely that Baldini, sensitive to the needs of the international market, which was particularly alive in Livorno, a cosmopolitan port frequented by English travelers on the Grand Tour, also turned to a production intended for that public, akin to that of artists such as Pompeo Massani, Arturo Ricci or Frédéric Soulacroix. Without representing the highest side of his activity, these works nevertheless reveal the versatility of an artist capable of adapting to different languages while maintaining a consistent drawing quality and a decorous taste, always measured.

Giuseppe Baldini was certainly not the most à la page painter present on Livorno, much less was he characterized by a marked propensity for experimentation, but he was certainly a man of many interests, capable perhaps of dealing with painting of neoclassical as well as well as romantic, interested in history as much as in current events, predisposed to the technique of fresco and oil but not disdaining his intervention in works of applied art; engaged in large public works but also in pieces blatantly made for a private market.

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.