Looking at ancient works of art and catching sight of its protagonists wearing glasses always seems funny and almost anachronistic. Sight problems, however, have plagued human beings since the dawn of time, and they mainly affected those who performed jobs of great precision or activities based primarily on reading and writing, such as monks. It was towards the end of the thirteenth century that, among this particular circle of intellectuals, they advanced the idea of creating something that would improve and mitigate the obnoxious snag.

The very first spectacles in history appeared would have been invented around 1286, probably in Pisa: we derive this date from the sermon of a Dominican friar, Guglielmo da Pisa, who said in 1306, in one of his sermons in the Florentine Lenten Lent, that “it is not yet twenty years that theart of making glasses, which make one see well, which is one of the best arts, and of the most necessary, that the world has” (the sermon constitutes, moreover, the first attestation of the word “glasses” in the Italian language). Confirmation may come from the Chronica antiqua conventus Sanctae Catharinae de Pisis, whose compiler, Fra Bartolomeo da San Concordio, writes in Latin that a friar of the monastery of Santa Caterina in Pisa, Alessandro della Spina, who died in 1313, was able to “recreate everything he saw, he knew how to do it,” and that he was also able to make “spectacles”(ocularia) “that someone else had invented but did not want to share, and he was able to create them and shared them with everyone.” We do not know the name of the craftsman who invented spectacles, but it is nonetheless certain that as early as the beginning of the 14th century they had to circulate and not only in Pisa and Tuscany, since in Venice a Capitolare dell’arte dei cristalleri of 1300 in which the sale of glass objects counterfeited to make them look like quartz was prohibited, and these included “roidi da ogli” (“discs for eyes”). We do not know for sure, however, whether glasses were invented earlier in Venice than in Pisa, because the documents do not help us clarify the dates: what is certain is that there was a thriving glass industry in both cities.

In any case, the earliest spec tacles consisted of two lenses mounted inside wooden or horn rims and fastened by a nail. The lenses, of the biconvex type, solved problems such as presbyopia and were, oftentimes, created using precious minerals such as clear quartz or beryl glass. And none of this would have been possible without the studies during the year 1000, of an Arab scientist known in Europe as Alhazen (Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Haytham; Basra, 965 - Cairo, 1040), who began to investigate the secrets of the cornea, and also tried to study what effects light was capable of causing on surfaces such as mirrors and lenses. Our ancestors, then, had no less vision problems than we do today; indeed these increased exponentially with theadvent of printing in 1455, which led, albeit slowly, to more and more people taking up individual reading. The book was generally smaller than a manuscript and was read by candlelight, and it was precisely this that contributed to an increase in the wide range of sight problems.

Spectacles initially became widespread among older people, and even Francesco Petrarch, who at the age of sixty began to lose his excellent eyesight, found himself hopelessly compelled to resort to the use of spectacles: we learn this from his letter Posteritati, where he states that he reluctantly had to give in to the necessity of having to use lenses. Subsequently, the market for spectacles expanded, as evidenced by a letter dated October 21, 1462, from the Duke of Milan, Francesco Sforza, in which he asks the ambassador of Florence for “three docene di dicti ochiali,” including those to correct vision defects “da zovene” (i.e. myopia), “da vechi” (presbyopia) and “comuni” (hypermetropia). However, despite the fact that the problem was widespread and pervasive, works of art representing subjects wearing glasses are extremely rare throughout history.

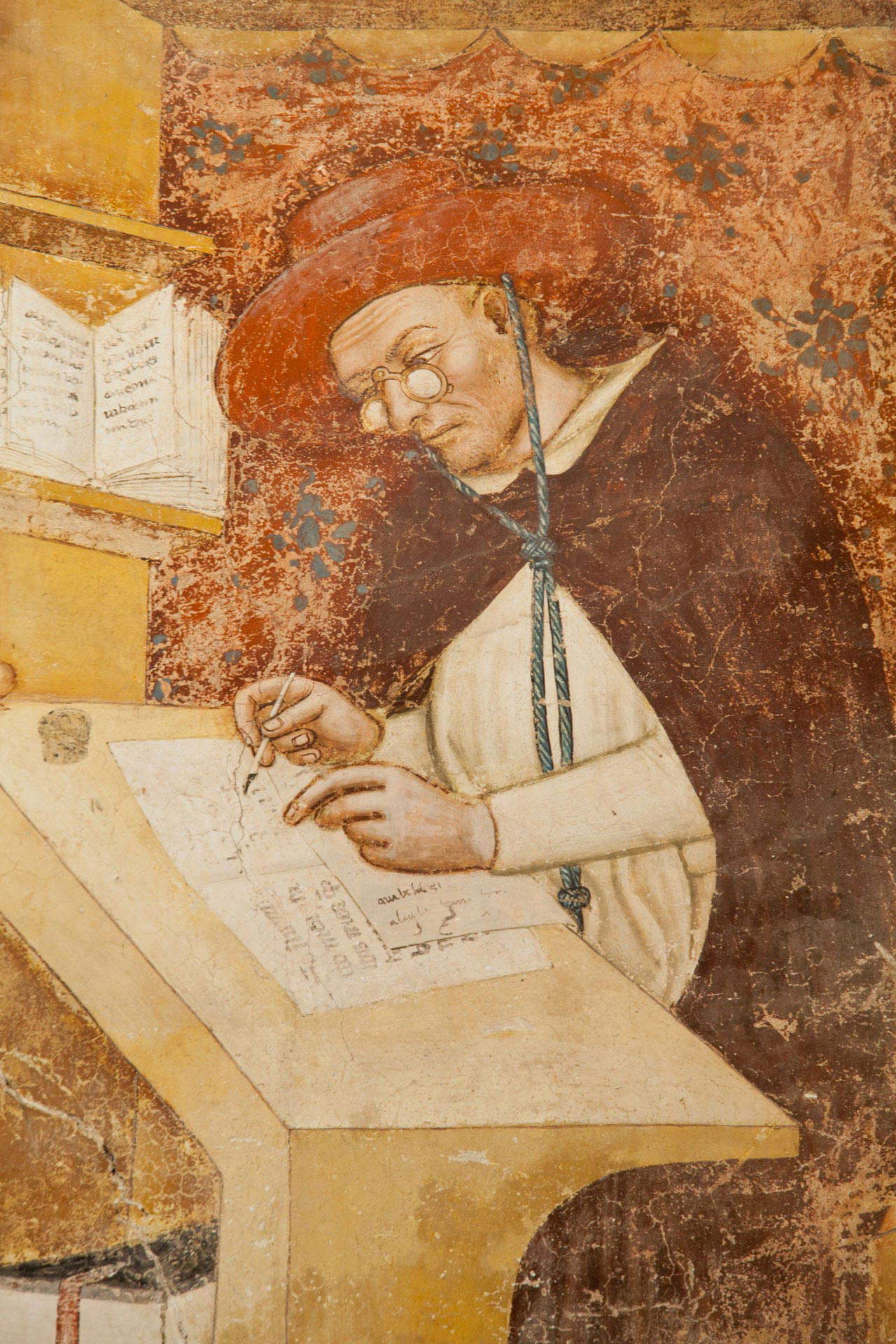

The first appearance, of this particular object in the history of Italian art dates back to 1352, when the artist Tommaso Barisini, known as Tommaso da Modena (Modena, 1326 - 1379), was commissioned to paint the chapter house of the convent of San Nicolò in Treviso with Dominican friars in their cubicles intent on reading or writing. Prominent among them is a portrait of Cardinal Hugh of Saint-Cher. Here the first cardinal of the Dominicans appointed as such in 1244 is portrayed by the artist one hundred years later, while immersed in writing with a rudimentary pair of glasses. An interesting solution to the enigma concerning the very scarce appearance of lenses throughout history has been suggested by Michael Pasco in his book L’histoire des lunettes vue par les peintres ( “The History of Glasses as Seen by Painters”). The Frenchman advances the hypothesis that, in Europe, wearing spectacles was seen as an embarrassing awkwardness, so much so that Napoleon I was always careful not to be seen in public while wearing his eyeglasses, and Louis XVI, despite being completely nearsighted, refused to wear them for the rest of his life. In Spain, however, it was the exact opposite. Since the 16th century, spectacles had been a sign of nobility and wealth because of their very high price tag, and that is precisely why they were constantly flaunted.

Historian Chiara Frugoni has, moreover, shown how, for medieval painting, spectacles became a multipurpose attribute: not only a reason for scientific attention, but above all a distinctive sign typical of scholars, doctors and, even earlier, of apostles and prophets. It becomes the context that determines its meaning, as in the case of the Vocation of St. Matthew painted by Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi; Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) for the Contarelli Chapel, thanks to which the detail of the spectacles remains anchored in the Gospel scene. Since 1599, Caravaggio had been showing a man standing intent on looking at coins with the aid of a pair of spectacles while the Christ bursts overbearingly onto the scene without, however, drawing the elderly man’s attention. In this case, the spectacles hold a symbolic value, alluding to blindness with respect to the divine call.

We find the character with the spectacles again in the great Vocation of Matthew painted by Ludovico Carracci (Bologna, 1555 - 1619) for the Compagnia dei Salaroli at Santa Maria della Pietà in Bologna and now preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in the Emilia capital. The Bolognese painter, during his stay in Rome in 1602, noted Caravaggio’s figure of the man with glasses in order to repropose it, characterizing it in a more grotesque sense, in his canvas. Compared to the painting in the Contarelli chapel, Ludovico Carracci added near the Jew to the inturbated figures, clearly broadening the call to Muslims or, perhaps, Levantine Jews.

The representation in painting of the well-known two-lens optical system was also used as a symbol of the alleged "Jewish myopia." In theEcce Homo on the back of Michael Pacher’s wooden altar preserved in the old parish church in the Gries district of Bolzano, Conrad Waider paints a Christ crowned with thorns and a Jew with money purse intent on observing, with his glasses, the one he does not believe to be the Messiah.

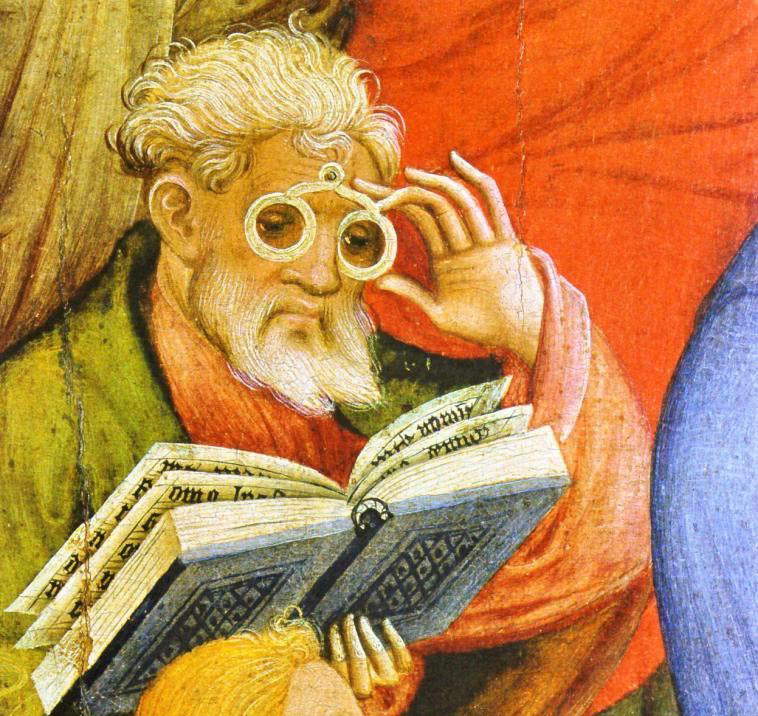

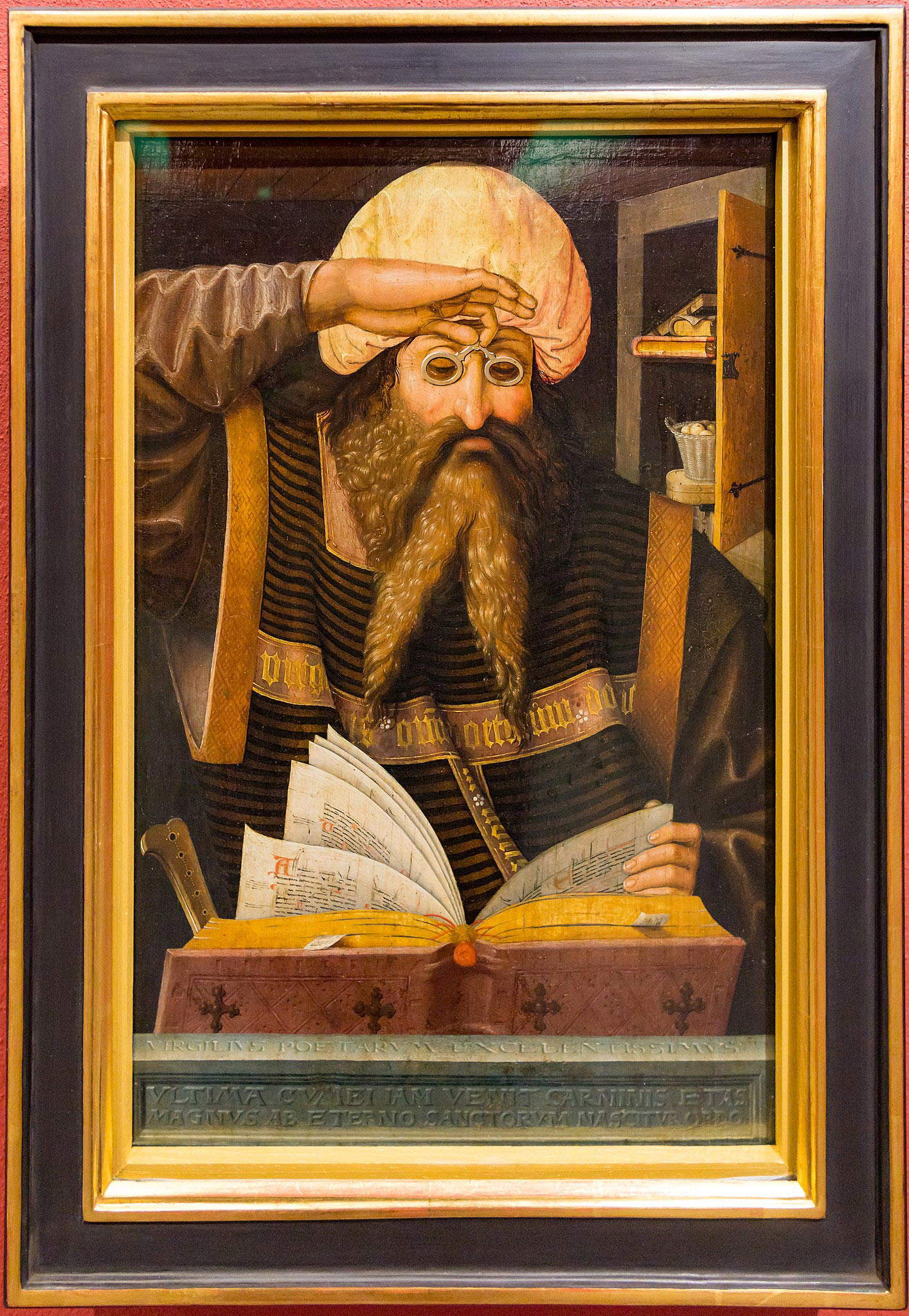

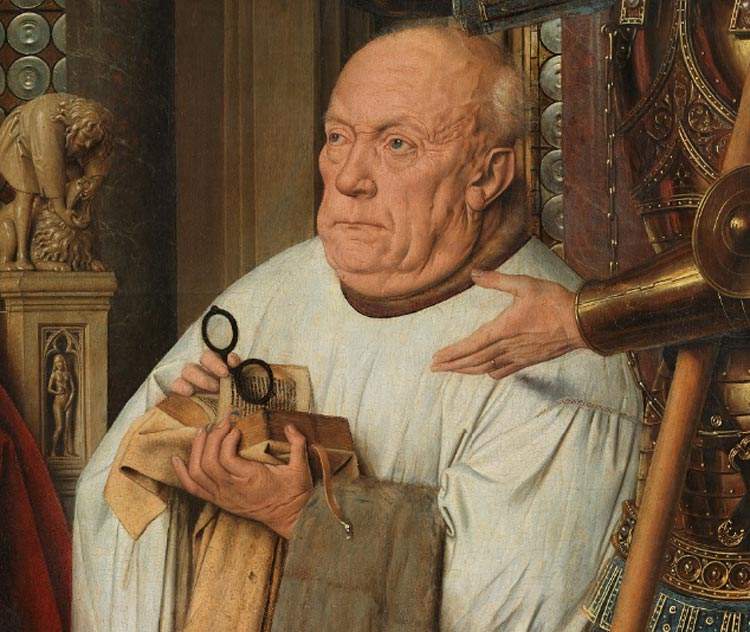

A status, a symbol, that created by the spectacles, which also began to be used to denote mainly wise and learned men, as in the case of the Bad Wildungen Passion Altarpiece, a 1403 work by the German painter Konrad von Soest (Dortmund?, c. 1370 - Dortmund, post-1422) in which “the apostle of spectacles” is depicted: the apostle wearing this primitive pair of spectacles is St. Peter as he is concentrating on reading the Holy Scriptures. Other saints wearing spectacles can be seen in the Montelparo polyptych by Niccolò di Liberatore known as the Pupil (Foligno, c. 1430 - 1502), which is in the Vatican Pinacoteca: there we find St. Philip and St. James both intent on reading with a pair of spectacles. In the same attitude is depicted another sage of antiquity, namely the poet Virgil, reading with a pair of spectacles in a painting by Ludger Tom Ring (Münster, 1422 - Braunschweig, 1484). Similar glasses, i.e., with rivet frames, are those seen in the Circumcision of Jesus by German painter Friedrich Herlin (Rothenburg ob der Tauber, c. 1430 - Nördlingen, 1500) preserved in the Church of St. James in Rothenburg ob der Tauber (the priest wears them), and particularly well known, although of different make (the frames in this case are arched), are those held by Canon Joris van der Paele in the very famous Madonna of Canon van der Paele, a masterpiece by Jan van Eyck (Maaseik, c. 1390 - Bruges, 1441) preserved in the Groeninge Museum in Bruges.

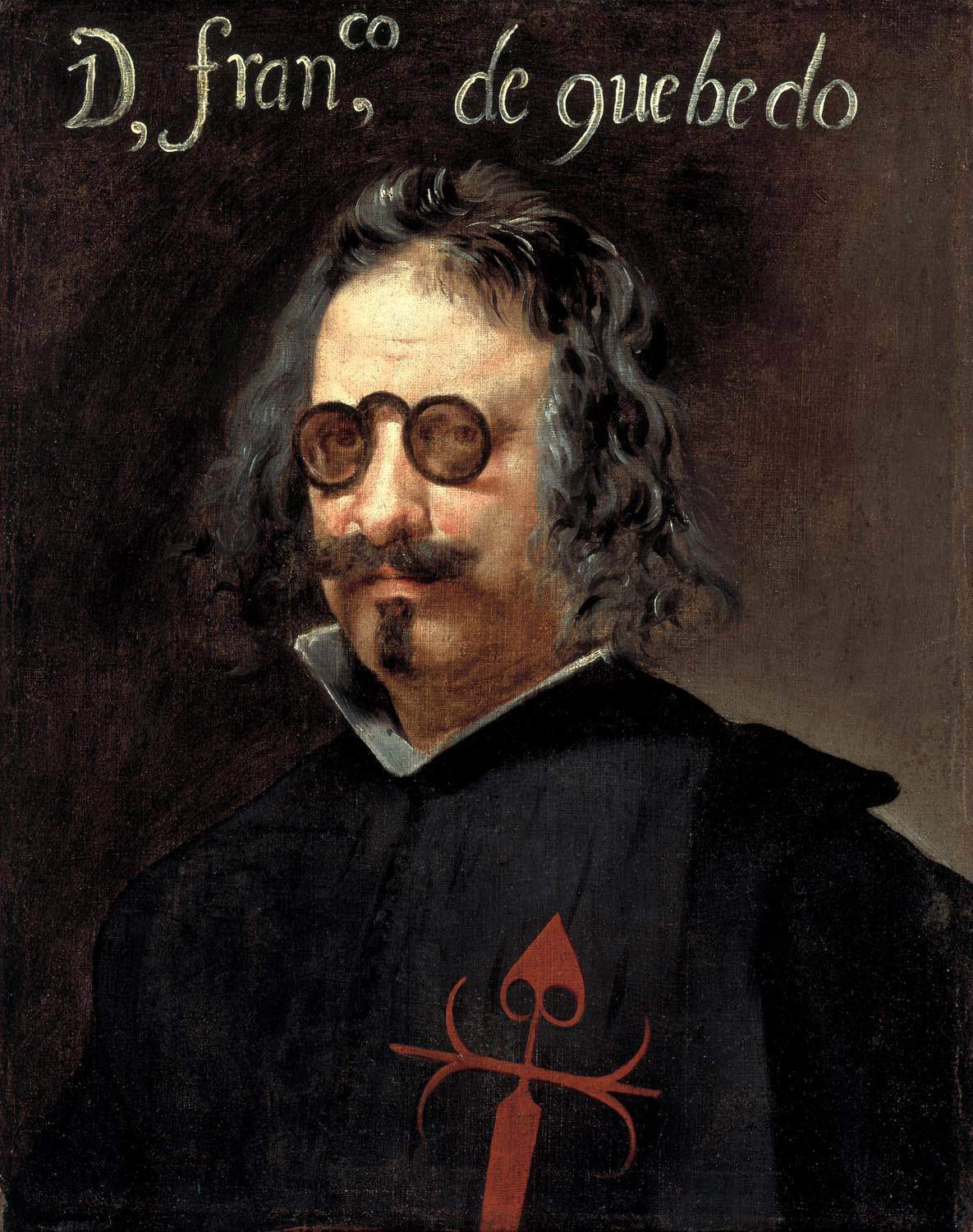

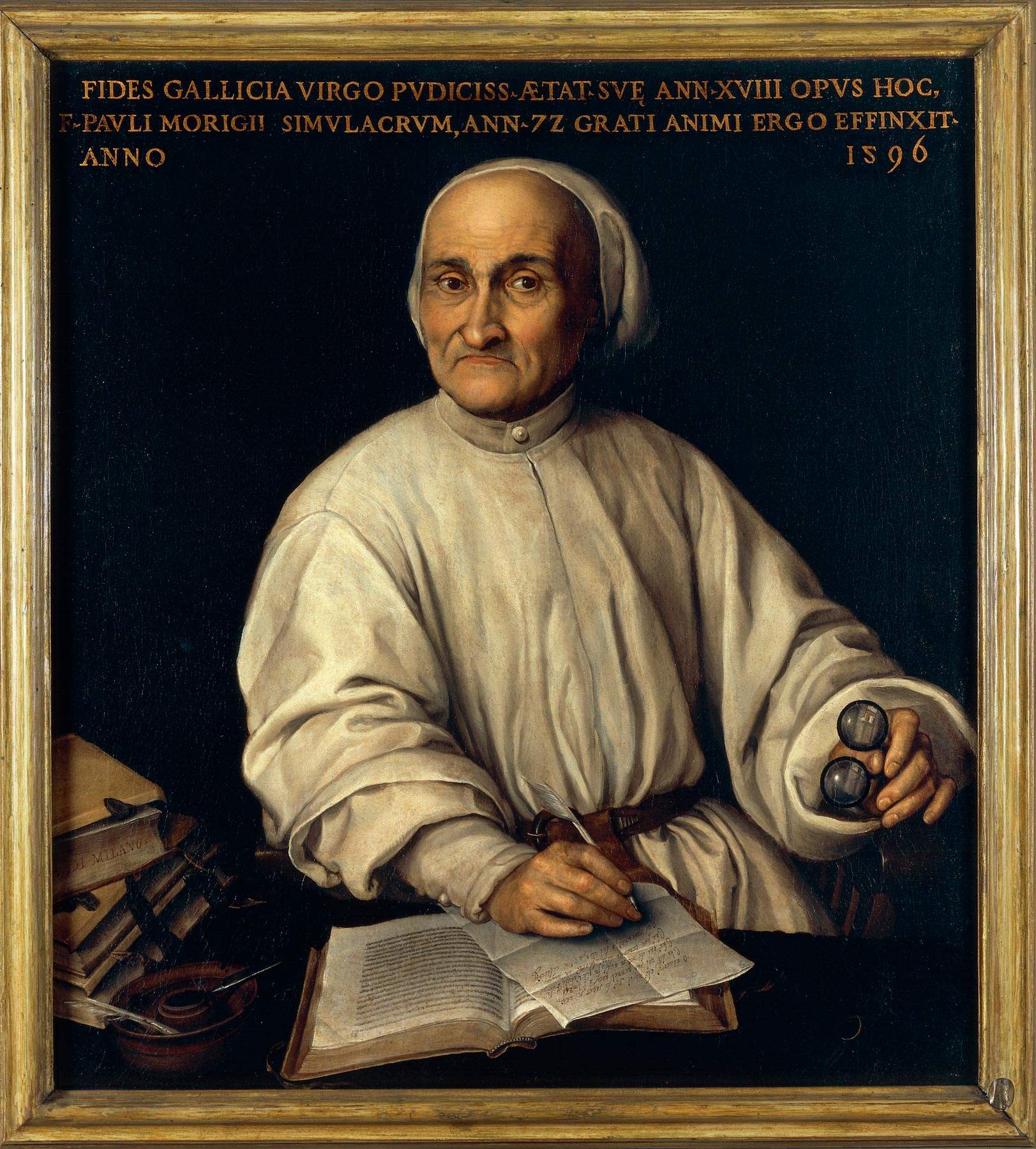

Very numerous and proud were the representations of the famous frames in Spain, as in the case of the Greek artist Domínikos Theotokópoulos, better known as El Greco (Candia, 1541 - Toledo, 1614), who portrays Cardinal Fernando Niño de Guevara wearing a pair of lace-rimmed spectacles. This famous portrait has become synonymous not only with El Greco’s art, but also with the whole of Spain and the Inquisition years. The person portrayed, became a cardinal in 1596 and Grand Inquisitor later. The Greek painter should have depicted the subject in the most sweetened and flattering manner possible, but he opted for painful honesty. The cardinal is depicted seated in a velvet armchair wearing a crimson cloak and is slightly tilted diagonally to add more depth to the composition. The head of the Spanish Inquisition gazes with icy detachment at the viewer through very black glasses and is surrounded by symbols of his elevated position. We also find spectacles in the portrait on canvas, formerly also attributed to Diego Velázquez, of the poet and writer Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas, who wore round, very thick spectacles on his nose, while a most peculiar and detail-oriented work is the Portrait of the Jesuit general, Paolo Morigia by Fede Galizia (Milan, 1578? - 1630). The general is a simply dressed man, with a stern gaze and surrounded by books and papers of whom is emphasized, not so much his religious being, but his appearance as a learned historian through the painstaking pictorial realization of a pair of spectacles. The “admirable pittoressa” used to analyze, almost scientifically and with detached realism, every single detail, and in this canvas her attention is directed precisely to the reflection of the window on the lens of the intellectual’s spectacles.

The spectacle has appeared repeatedly, albeit sporadically, from the fourteenth century through Caravaggio to contemporaries such as Otto Dix, becoming a symbol of blindness, fine intelligence or representation of high and important status. Initially hated and mistreated, it did not happily and overwhelmingly create a place for itself in the history of Western art, but was met with parsimonious calm and accepted almost with resignation, becoming, today, one of the most beloved accessories in the fashion market.

The author of this article: Francesca Anita Gigli

Francesca Anita Gigli, nata nel 1995, è giornalista e content creator. Collabora con Finestre sull’Arte dal 2022, realizzando articoli per l’edizione online e cartacea. È autrice e voce di Oltre la tela, podcast realizzato con Cubo Unipol, e di Intelligenza Reale, prodotto da Gli Ascoltabili. Dal 2021 porta avanti Likeitalians, progetto attraverso cui racconta l’arte sui social, collaborando con istituzioni e realtà culturali come Palazzo Martinengo, Silvana Editoriale e Ares Torino. Oltre all’attività online, organizza eventi culturali e laboratori didattici nelle scuole. Ha partecipato come speaker a talk divulgativi per enti pubblici, tra cui il Fermento Festival di Urgnano e più volte all’Università di Foggia. È docente di Social Media Marketing e linguaggi dell’arte contemporanea per la grafica.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.