Lorenzo the Magnificent (Florence, 1449 - Careggi, 1492) has gone down in history as one of the greatest patrons of art and one of the most munificent patrons of all time. His vast economic resources enabled him to finance an impressive number of cultural enterprises (from the arts to literature, from music to public building), which earned him the nickname by which he is universally known. And as a true father-master of late fifteenth-century Florentine politics (in this sense, the judgment of a great historian, Francesco Guicciardini, on him is not benevolent), he could afford not only to support a great many commissions, but also to direct the taste of the time, given also his vast culture and given the length and stability of his de facto government (Lorenzo, formally, did not have any major appointments, as all the Medici before him: he must be seen as a kind of primus inter pares), which lasted from 1469 to 1492.

All this allowed the Magnifico to direct, for more than two decades, the fortunes of Florentine culture, to which was imprinted, writes art historian Liana Castelfranchi Vegas, “a strongly unified character in each of its fields,” and the cohesive element wasantiquity: “the literature, art, and philosophy of the classical age, known, studied, and vague, constitute a heritage of thoughts and images that enter into art and constitute, as Chastel says, a pass for the ’modern.’” Lorenzo the Magnificent is credited with several merits: having been the first to think of a special training place for artists, namely the Garden of San Marco, where Michelangelo also studied; revolutions in the field of architecture, the one in which his patronage was perhaps best expressed (Castelfranchi Vegas identifies three innovative lines: his interest in the urban balance of architectural achievements, his interest in centrally planned buildings, and his revival of the villa all’antica); his intuition of the role of art as a method of enhancing personal prestige (although, unlike his predecessors, of whom he was much more cultured, Lorenzo did not seek ostentation); and his interest in youth.

There are many works by the Magnifico that can be seen today in Florence (and beyond), in the city’s museums and churches. And of course countless are those that came into being thanks to the cultural climate he fostered. We have collected in this gallery ten of his most famous direct commissions: as a criterion, we have chosen to include only those works about which we have definite or highly probable news (thus on which there is substantial agreement by critics). We have therefore not included works commissioned by members of the family who were also affected by the cultural climate imprinted by the Magnifico (beginning with Botticelli’s Venus and Primavera, which are owed, if anything, to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, known as the Popolano, the Magnifico’s cousin), nor those for which the commission is doubtful (e.g. Verrocchio’s Lady with a Small Bouquet, believed by some to be a portrait of Lucrezia Donati, the Magnifico’s lover and muse, or Luca Signorelli’s Medici Madonna, or Botticelli’s Pallas and the Centaur in the Uffizi, and others: questions often arise from the fact that in the ancient inventories the patron is recorded simply as “Lorenzo de’ Medici” and thus there has often been confusion between the Magnifico and the Popolano). We have made one exception for Verrocchio’sIncredulity of Saint Thomas, because although not directly commissioned by the Magnifico, his role was instrumental in Verrocchio being awarded the work. Here, then, are ten works that we can admire today thanks to the generosity of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

1. Villa Medicea of Poggio a Caiano

This is Lorenzo the Magnificent’s most famous architectural feat: work probably began in the 1480s and the design is due to Giuliano da Sangallo (Florence, 1445 - 1516), who drew on Alberti’s lesson by designing a symmetrical and harmonious building on top of a hill. The loggias allow a perfect connection between the interior and the exterior, the pediment that recalls that of classical temples is the most direct reference to classicism, and the rooms are situated around a central hall-these are all elements that other architects would later take up. However, the Magnifico did not have time to see it finished because he died before the work was completed, which was interrupted when the Medici were exiled from Florence. Only between 1513 and 1520, with the return of the Medici from Florence, was the villa finished at the behest of Giovanni (Florence, 1475 - Rome, 1521), son of Lorenzo, who had meanwhile ascended to the papal throne under the name of Leo X. Today the villa is owned by the state and is one of the museums that make up the Polo Museale della Toscana.

|

| Medici Villa of Poggio a Caiano. Ph. Credit Niccolò Regacci |

2. Basilica of Santa Maria delle Carceri, Prato

The construction of the basilica of Santa Maria delle Carceri, one of the most beautiful and well-known basilicas in Prato (which had been placed under the rule of Florence for more than a century) was supported by the Magnifico, who again called Giuliano da Sangallo for its realization, who again drew inspiration from Alberti’s theories on the central plan (the basilica has a Greek cross plan). Construction began in 1486 and finished in 1495, three years after the death of the Magnifico: the work, however, remained unfinished (and remains so to this day: the marble facing of the facade, in the typical white-green two-tone, is partly incomplete). Great artists such as Domenico del Ghirlandaio and Andrea della Robbia were called to decorate the interior. The idea of building a church arose as a result of events believed to be miraculous that occurred in the summer of 1484 before the effigy of a Madonna and Child painted on the Stinche prison in Prato, which stood on the square on which the church stands.

|

| Basilica of Santa Maria delle Carceri, Prato. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

3. Sacristy of Santo Spirito, Florence

The famous sacristy, another masterpiece by Giuliano da Sangallo, was added to the basilica of Santo Spirito at the initiative of Lorenzo the Magnificent: the construction lasted from 1489 to 1492. In this case, the architect drew inspiration from the solutions of Filippo Brunelleschi, creating a building with an octagonal plan, which recalled the shape of the Baptistery of Florence. The interior is characterized by the presence of decorative elements made of pietra serena: pilasters, cornices, entablatures contribute to the overall balance of the whole structure. The sacristy is also famous because its interior houses one of Michelangelo Buonarroti ’s (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564) masterpieces, the Crucifix of Santo Spirito.

|

| Sacristy of Santo Spirito, Florence |

4. Vase of Lorenzo the Magnificent

Contrary to what the collective imagination might lead us to think, the Magnifico’s tastes focused on sculpture and applied arts rather than painting. Lorenzo de’ Medici was very fond of objects, and the so-called “Vase of Lorenzo the Magnificent,” preserved today in the Treasury of the Grand Dukes in the Pitti Palace, is a clear example. It is an object just over forty centimeters high, made of red jasper with fine decorations in fire-gilt silver and translucent enamels. It is a vase with two handles, the body of which can be dated to the 14th century: it was instead commissioned by Lorenzo (and precisely in the 1560s) to mount the lid. In addition, the lord had his initials “-LAV-R-MED-” affixed to the vase. A work of probable Venetian manufacture (similar ones were produced in the lagoon city in the 14th century), it also experienced some tribulation after the Medici’s exile from Florence: it came into the possession of the Tornabuoni, a family loyal to the Medici, and later ended up in Rome in 1495, where it was recovered by Giulio de’ Medici (Florence, 1478 - Rome, 1534), the future Pope Clement VII, who in 1532 made a gift of it to the basilica of San Lorenzo, another place linked to the family. It was transferred to the Uffizi in 1785 and passed to the Treasury of the Grand Dukes in 1921.

|

| Venetian manufacture and Florentine artisans, Vase of Lorenzo the Magnificent (14th-century vase, mount 1463-1465; red jasper, fire-gilt silver, translucent enamels, height 42.5 cm; Florence, Tesoro dei Granduchi) |

5. Verrocchio, Incredulity of Saint Thomas.

The Incredulity ofSt. Thomas, a masterpiece by Verrocchio (Andrea di Michele di Francesco di Cione; Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488), is the first, important public sculpture whose creation can be traced to Lorenzo the Magnificent. Officially, Verrocchio received the commission from the Arte di Calimala (the merchants’ guild), which would have destined it for its niche in the church of Orsanmichele, but Lorenzo and his father Piero il Gottoso (Florence, 1416 - 1469), as workers of the Mercanzia, most likely determined the choice of the artist, who had already worked for the Medici (moreover, it was Piero who negotiated, in 1464, the purchase of the bronze needed for casting). After Piero’s death in 1469, the work was supervised by Lorenzo, who was able to see the work completed in 1483. However, Verrocchio had some trouble getting paid: in fact, we know that in the year of his death he had yet to collect two hundred florins from the Arte di Calimala.

|

| Verrocchio, Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1467-1483; bronze with gilding, 241 x 140 x 150 cm; Florence, Museo di Orsanmichele) |

6. Verrocchio, Tomb of Piero and Giovanni de’ Medici.

The monument that houses the remains of Piero il Gottoso, father of the Magnifico, and Giovanni di Cosimo de’ Medici (Florence, 1421 - 1463), younger son of Cosimo il Vecchio (and thus brother of Piero and uncle of Lorenzo), was commissioned from Verrocchio shortly after Piero’s death and was completed in 1472. The tomb, made of marble, bronze, porphyry, and pietra serena, is an arcosolium funerary monument similar to those that had been made a few years earlier by Bernardo Rossellino and Desiderio da Settignano, and is one of the masterpieces of Verrocchio’s ornamentation (note the bronze decorations on the sarcophagus, with the plant motifs enveloping it, the lion paws similar to those carved in marble by Desiderio in the funeral monument of Carlo Marsuppini, or the peculiar turtles supporting the marble plinth): the tomb, in fact, is a work “all form and matter,” as art historian Gabriele Fattorini has described it. On the plinth, the names of Lorenzo and Giuliano, Piero’s sons, appear. The work can be seen in the Basilica of San Lorenzo.

|

| Verrocchio, Tomb of Giovanni and Piero de’ Medici (1469-1472; marble, bronze, porphyry and pietra serena, 358 x 601 cm; Florence, Basilica of San Lorenzo). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

7. Verrocchio, Spiritello con pesce (putto with dolphin).

According to Giorgio Vasari, the world-famous putto with dolphin was commissioned by the Magnifico for the Medici villa in Careggi, while today it is in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, and has undergone a thorough restoration ahead of the major exhibition dedicated to Verrocchio held in early 2019 at Palazzo Strozzi. “Endowed with unestrema naturalezza,” art historian Federica Siddi recently wrote, “the Palazzo Vecchio child, in his rapid gait clutching the elusive aquatic animal, gives the measure of the skill Verrocchio achieved in tackling the challenges associated with representing a free figure in space.” Moreover, the sculpture was reminiscent of ancient statuary since child figures abounded in classicism, and Verrocchio was able to infuse this genre with an unprecedented vivacity. Originally, the work decorated a fountain.

|

| Verrocchio, Tomb of Giovanni and Piero de’ Medici (1469-1472; marble, bronze, porphyry and pietra serena, 358 x 601 cm; Florence, Basilica of San Lorenzo) |

8. Antonio del Pollaiolo, Hercules and Antheus.

The bronze, just 45 centimeters high, is a small masterpiece by Antonio del Pollaiolo (Florence, c. 1431 - 1498) and depicts one of the twelve labors of Hercules, the slaying of the giant Antaeus in the desert of Libya. According to myth, Antaeus received strength from the earth (his mother was Gaea, goddess of the earth), and to get the better of him Hercules was therefore forced to fight by holding him up off the ground. Antonio del Pollaiolo depicts Hercules at the very moment when he is holding Antaeus up in the air by clutching him to himself. The sculpture well embodies the vision of classicism according to the Magnifico: the ancient myth is thus reinterpreted by virtue of its allegorical meaning (Hercules had become a kind of symbol of virtue capable of dominating vice). Hercules, Gioia Mori wrote, “was in fact interpreted as the embodiment of the positive ideal of virtue and courage that annihilates the beast, the symbol of evil, vice and brute force. According to Christian exegesis accepted by Neoplatonic doctrines Hercules was, moreover, a figure of Christ.” From a formal point of view, the very powerful movement of the two figures was something that had never been seen in the Renaissance.

|

| Antonio del Pollaiolo, Hercules and Antheus (c. 1475; bronze, height 45 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

9. Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs.

A youthful masterpiece executed for the Magnifico in the Garden of San Marco by a Michelangelo who was little more than 15 but whose talent had already been well sensed by Lorenzo, the relief depicts the fight between the centaurs and the Lapiths: according to Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo’s first biographer, the theme was suggested by Agnolo Poliziano, a poet of the Laurentian court and a great friend of the Magnifico. The work depicts the brawl that broke out between the centaurs and the Lapiths during the wedding celebrations for the marriage of Princess Hippodamia, who was to be married to the son of the Lapith king (who in the brawl with the drunken centaurs got the better of them). This is a work that exemplifies the battle between reason and instinct, and thus finds an allegorical interpretation that fits well with the neo-Platonic philosophy that animated the Florentine culture of the time. The relief, highly original in the way Michelangelo treats space (the figures are arranged in multiple planes) is in a state of unfinished state: it is assumed that Michelangelo interrupted the work when Lorenzo passed away in 1492.

|

| Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs (1490-1492; marble, 80.5 x 88 cm; Florence, Casa Buonarroti). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

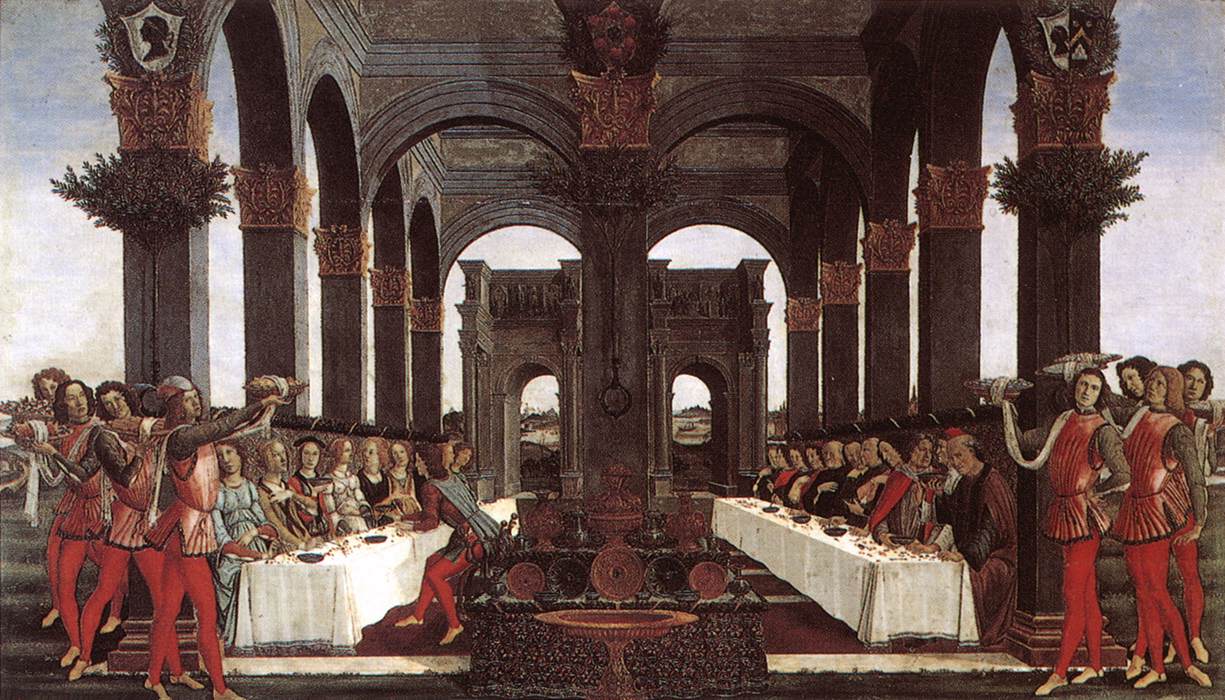

10. Sandro Botticelli, Stories of Nastagio degli Onesti.

The four panels that decorated a wedding chest (three are in the Prado in Madrid, while one is in Florence, in the Pucci Palace) were commissioned from Sandro Botticelli (Florence, 1445 - 1510) in all likelihood by the Magnifico, who intended to give a wedding gift to Giannozzo Pucci on the occasion of his marriage to Lucrezia Bini celebrated in 1483. The panels all remained together in the Pucci Palace until the mid-19th century. The work tells the story of Nastagio degli Onesti as told by Giovanni Boccaccio in the Decameron: Nastagio was a nobleman from Ravenna who wanted to marry a woman who, on the contrary, did not intend to give him up. Nastagio, disappointed by the refusal, after contemplating suicide decided to leave Ravenna: in the Classe pine forest, not far from the city, the ghost of a knight chasing a naked woman appeared to him. At the end of the chase, the woman was mauled by the horseman’s dogs: the latter, on reaching Nastagio, had confessed to him that that was his punishment for having committed suicide because of a woman’s rejection, and the two were thus condemned to repeat that terrible scene every Friday. Nastagio therefore decided to organize a banquet for the following Friday, inviting his beloved, who, after witnessing the condemnation of the knight and the woman who had rejected him, decided not to reject Nastagio again.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Nastagio degli Onesti, fourth episode (1483; tempera on panel, 83 x 142 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pucci) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.