The first treatise devoted to scientific perspective is the work of Piero della Francesca (Borgo San Sepolcro, c. 1412 - 1492): it is De Prospectiva Pingendi, transmitted by seven manuscripts. Three are those that have brought us the text in the vernacular: the Ms. Parm. 1576 from the Palatina Library in Parma, the Ms. Reggiano a41/2 from the Panizzi Library in Reggio Emilia, and the Ms. D 200 inf. from the Ambrosiana Library in Milan. The Milan manuscript is a 16th-century copy, the Reggio Emilia one contains some corrections and annotations by Piero (as well as his drawings), while the Parma manuscript is instead entirely autograph. The other four manuscripts (preserved at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the Bibliothèque Municipale in Bordeaux, the British Museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris), on the other hand, contain the Latin translation made by Matteo di ser Paolo d’Anghiari.

Giving us news of the precedence of the vernacular version and the name of the translator is the great mathematician Luca Pacioli, a friend of Piero della Francesca, who wrote thus in his book De summa arithmetica: “El sublime pictore (a li dì nostri ancora vivente) maestro Pietro de li Franceschi nostro conterraneo del Borgo San Sepolchro hane in questi dì composto degno libro de ditta prospectiva. In which highly de la pictura parla ponendo sempre al suo dir ancora el modo e la figura del fare. El quale tutto habbiamo lecto e discorso, el qual lui feci vulgare, e poi el famoso oratore, poeta e rhetorico greco e latino (suo assiduo consotio e similmente conterraneo) maestro Matteo lo reccò a lingua latina ornatissimamente de verbo ad verbum con exquisiti vocabuli”. The idea of writing the text in the vernacular and then having it translated into Latin was in response to the need to get the treatise to as wide an audience as possible and not to preclude it from becoming part of the splendid library of Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino.

We do not know with certainty the date when De Prospectiva Pingendi was written. Piero della Francesca, in the dedicatory epistle of another of his important treatises, the Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus, recalled that he had given the treatise on perspective to Federico da Montefeltro, who died in 1482: the De Prospectiva Pingendi, therefore, was necessarily written before this date, and scholars generally tend to place it between 1475 and 1477, the time of Piero’s stay in Urbino, during which he was most likely able to consult the Euclidean manuscript De aspectuum diversitate, a treatise on optics, now preserved in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

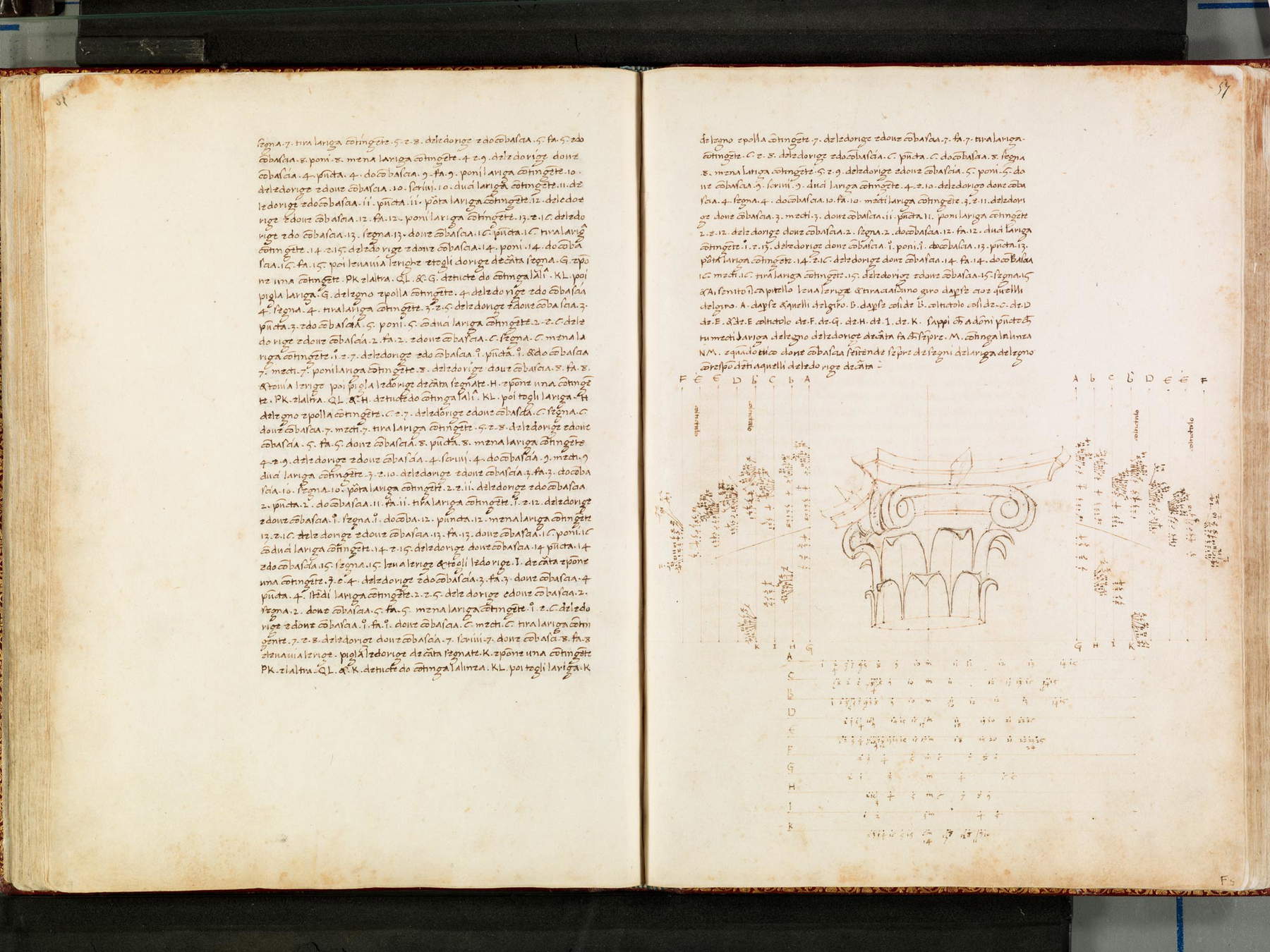

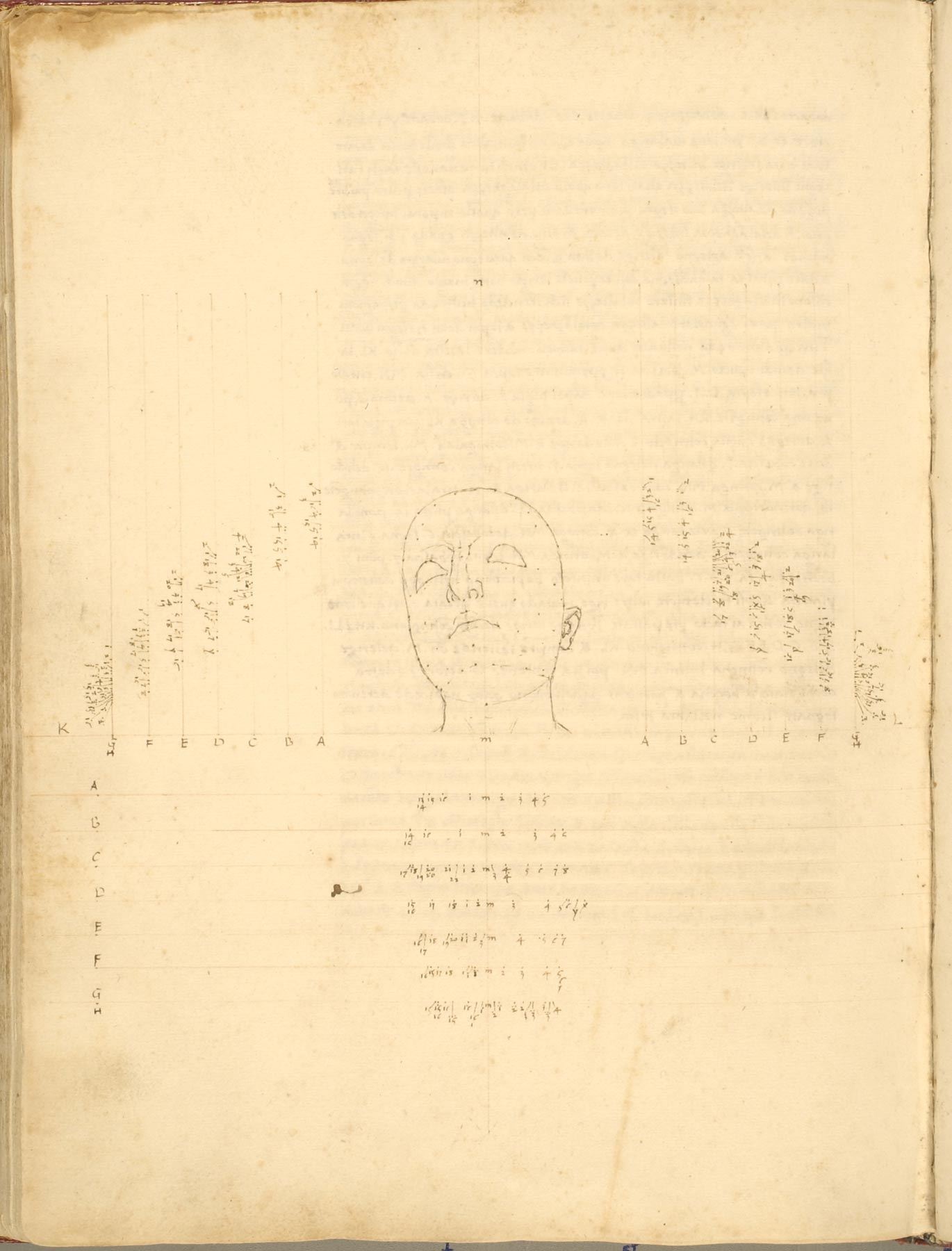

It is Piero della Francesca himself who outlines from the introduction the theme of De Prospectiva Pingendi, dedicated to the theme of commensuratio (“which we say prospectiva,” Piero adds), one of the three fundamental elements of painting, along with “drawing” and “coloring”: “Commensuratio diciamo essere essi profili et contorni proportionalmente posti nei lughi loro.” The Borghi artist identifies five essential elements of commensuratio, namely the eye, the shape of the object being viewed, the distance between the object and the eye, the lines joining the eye and the object, and the plane on which perspective depends. Interestingly, Piero keeps himself equidistant between a treatise that deals with problems strictly related to optical theories and an empirical application of perspective: the treatise, divided into “propositions” and carried out, beginning with the twelfth proposition, by means of perspective problems that are presented to the reader in ascending order of difficulty, accompanied by Piero della Francesca’s autograph drawings, is intended to give the reader demonstration of the solutions of the problems through geometric principles.

The treatise is divided into three books, which are respectively devoted to plane figures, elementary solids, and more complex bodies. The first book opens with eleven propositions in which Piero della Francesca addresses the fundamental theorem of Euclidean optics (“Omni quantity se rapresenta under angle in the eye”) and clarifies the concepts of similarity and geometric proportion. The discussion on perspective begins with the twelfth proposition: for example, in 14 and 15 the artist explains how to construct the floor grid that allows objects to be scaled in perspective, while in those from 16 to 20 the artist addresses the problem of perspective foreshortening of regular polygons (the triangle, pentagon, hexagon, octagon, and hexadecagon), and presents problems on adding and reducing surfaces from a square, or on cutting out polygons on plane surfaces. The first book concludes with the thirtieth proposition, addressed to those who “stand in dubitatione la prospectiva non essere vera scientia, judging the false by ingnorança”: instead, Piero intends to demonstrate that perspective is true science with a geometric demonstration on the problem of marginal aberrations, that is, the deformed representation of reality resulting from projections starting from very wide visual angles. The artist, writes Chiara Gizzi, who in 2016 edited the critical edition of De Prospectiva Pingendi for Ca’ Foscari Editions, responds “by establishing that the eye must remain fixed in the term (’perché i[n] quello termine l’occhio sença volgiarse vede tucto il tuo lavoro, ché, se bisognasse volgere, serieno falsi i termini perché serieno più vederi’, I.30.14) and that the ideal relationship between the eye and the term is two-thirds of a right angle.”

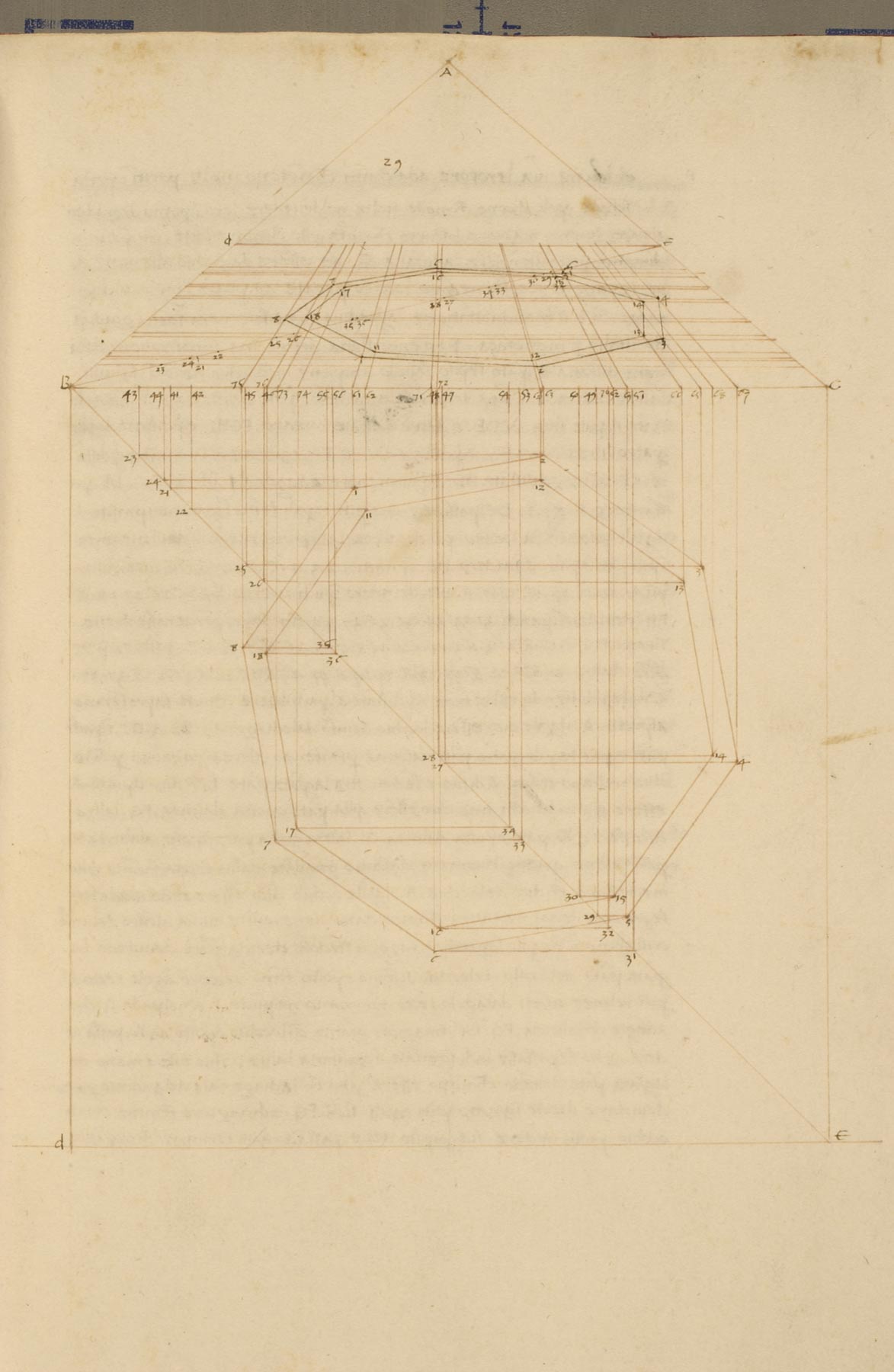

The second book, which discusses elementary solids, opens with a definition of “solids” (“Body has in itself three demensions: longitude, latitude et altitude”), and continues with several problems through which Piero della Francesca explains how to foreshorten bodies in perspective, always in order of increasing difficulty, thus starting with the simplest solids (such as the cube) and then moving from abstract geometric figures to real objects, for example, pillars, well-castles, buildings or parts of buildings (such as a temple with an octagonal base or a cross vault). The second volume concludes with proposition 12, in which Piero again addresses the problem of marginal aberration, in this case of a colonnade, stating that if in the perspective drawing the side columns appear larger larger than the central ones, in contradiction to our visual impressions, the proportions must not be correct since “de necesità se rapresenta nel termine magiore la più remote che non fa la più propinqua; che è il proposto.” That is, it is “the mathematical demonstration,” wrote scholar Massimo Mussini, that “assures of the certainty of such a result.”

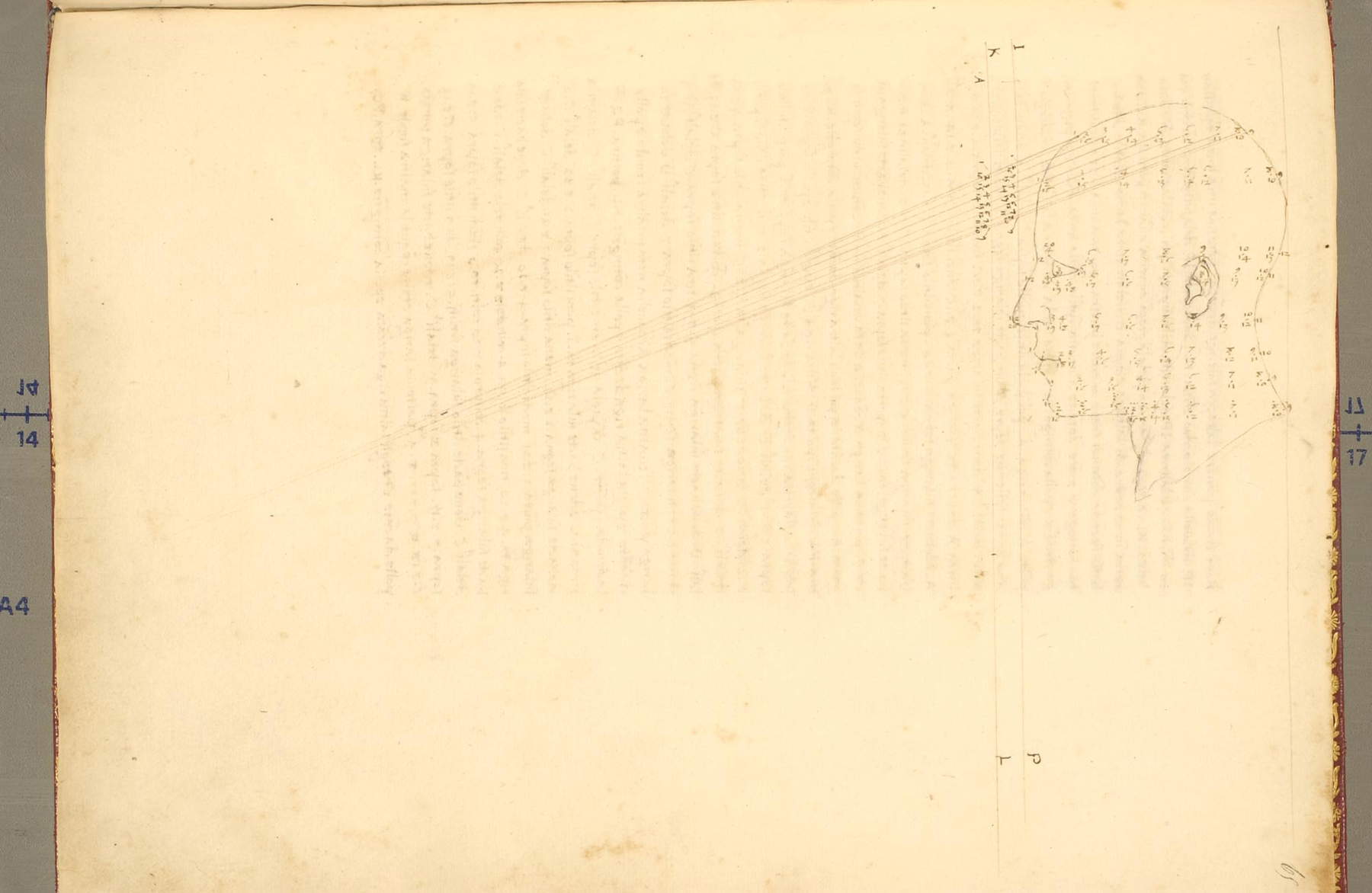

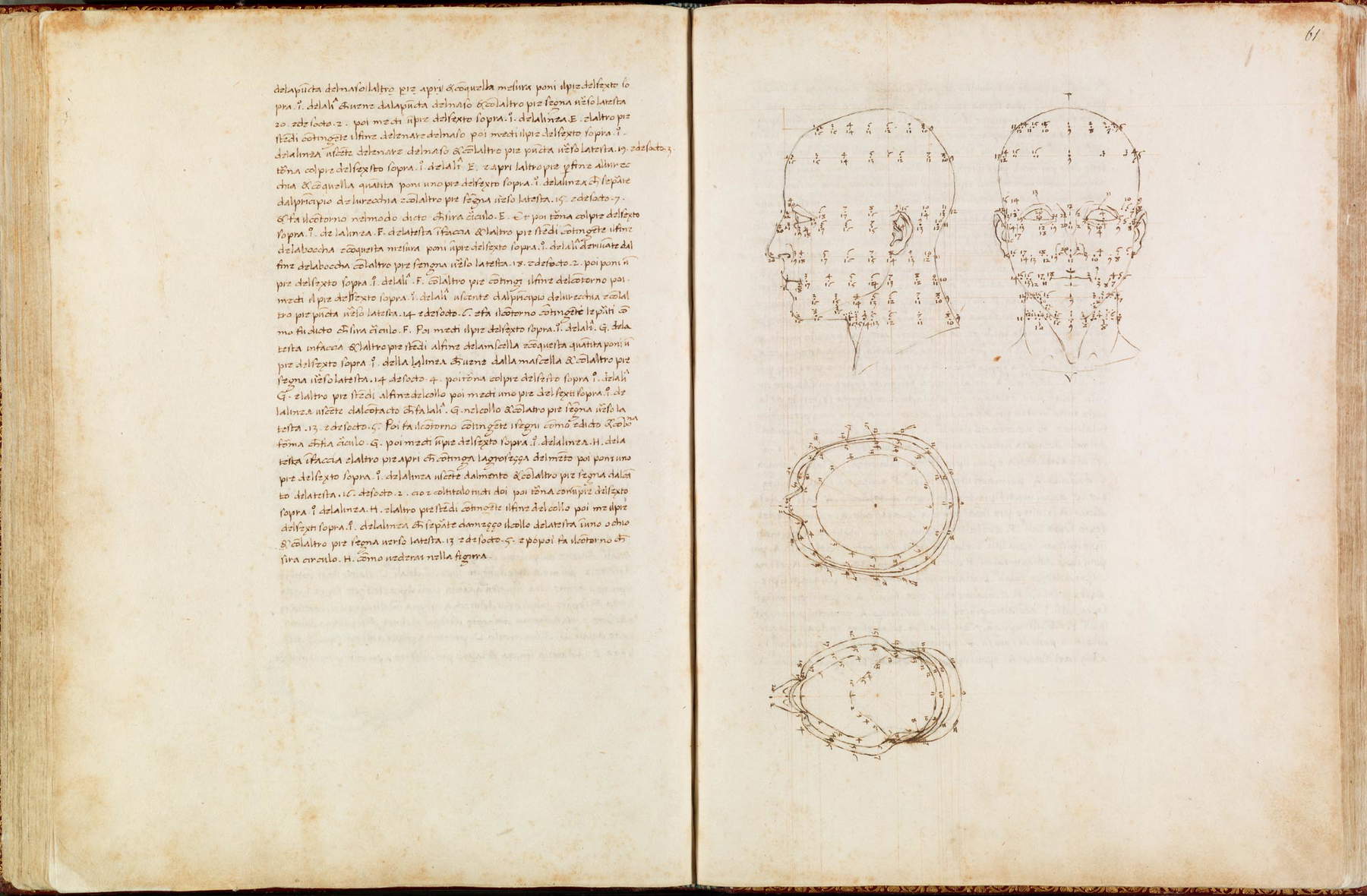

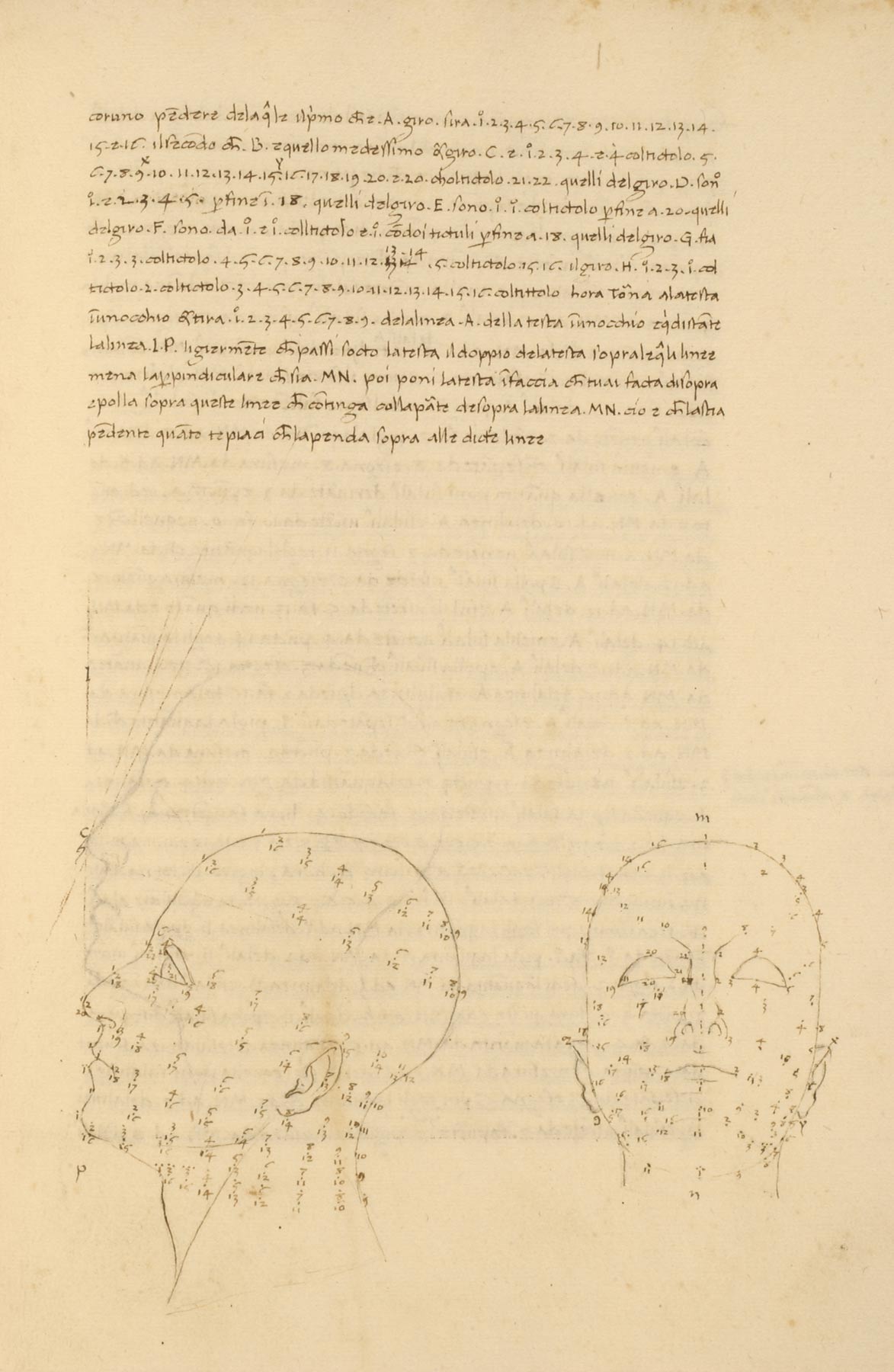

The third book begins with a proem in which Piero della Francesca returns to the validity of perspective as a science, addressing the “many painters” who “blame perspective because they do not understand the force of the lines et degl’angoli che da essa se producano: con li quali commensuratamente onni contorno e lineaamento se descrive.” Piero intends instead “to show how necessary this scientia is to pictura”: according to the artist, saying “perspective” is equivalent to saying “things seen from afar, represented under certain given terms with proportion, according to the quantity of their distances.” And since, in his opinion, painting is nothing but “demonstrations of surfaces and of bodies degraded or increased in term, placed according to the fact that true things seen by the eye socto different angles s’apresent themselves in the said term,” then consequently perspective is necessary since it “discerns all quantities proportionally commo vera scientia, demonstrating the degrading and increasing of any quantity by force of lines.” The last volume of De Prospectiva Pingendi speaks of the “degradationi de’ corpi compresi da diverse superficie et diversamente posti,” and in particular of “more deficile bodies,” which consequently require other methods of foreshortening. “Reiterating that the ability to delineate figures is a necessary condition for being able to operate their perspective reduction,” writes Gizzi, “Piero expounds the method by plan and elevation of which he offers the first written codification”: the exercises proposed by the artist thus concern complex bodies such as the mazzocchio, the column base, the capital, and even the human head, foreshortened by Piero in the treatise’s most famous illustrations. Piero’s method involves foreshortening the figure in plan (“largheçça”) and elevation (“alteçça”), and a point of view is then fixed, through the use of a needle with a thread (Piero suggests using a ponytail hair), and then drawing, Gizzi reconstructs, “a line parallel to the plane that constitutes the term, where the lines will be placed (one of wood for the width and two of paper for the height). Having placed the line on the term, one pulls the thread to the point to be reported on the line itself and where the thread touches (bacte) the line one marks the point.” This operation is repeated for all the sections into which the object is broken down, and once all the points are returned to the lines, the figure can be reconstructed.

This is a particularly complicated method especially for the foreshortening of the human figure, so much so that the artist, in order to demonstrate his theories, gives the reader a very long treatment. Finally, the last two propositions teach the reader to reduce into perspective a cooler (a vessel for keeping wine cool) placed on a dining table, and a ring hanging from a ceiling. The work concludes with two encomiastic compositions in Latin, found only in the translated codices and in the Palatine Library manuscript.

The Parma codex, restored in 2010 by Studio Crisostomi of Rome, has a 19th-century red morocco binding on quadrants, decorated with floral motifs in gold, and consists of nine fascicles: on the verso of the guard paper (the unprinted sheets placed at the beginning and end of the book, which protect the text, are called “guard papers”) appears a reference to the inventory of the library collection of the priest and scholar Michele Colombo (Campo di Pietra, 1747 - Parma, 1838), in whose catalog, also preserved at the Palatina, the “ms. pregevolissimo” a value of 200 paoli, and is reported to have repeatedly offered ten zecchini for its purchase. Colombo, again, notes that “Sommamente pregevole si è questo codice che, secondo ogni apparenza, è l’autografo stesso dell’Autore.” We do not know how Colombo had obtained the manuscript: what is certain is that the autograph of De Prospectiva Pingendi reached the Palatine Library in 1843, along with all the manuscripts in the abbot’s collection. And since then, the highly prized Renaissance codex has linked its fate to that of the Parma institution. A book that, wrote Leonardo Farinelli, director of the Palatina from 1991 to 2007, “alone could make any library famous.”

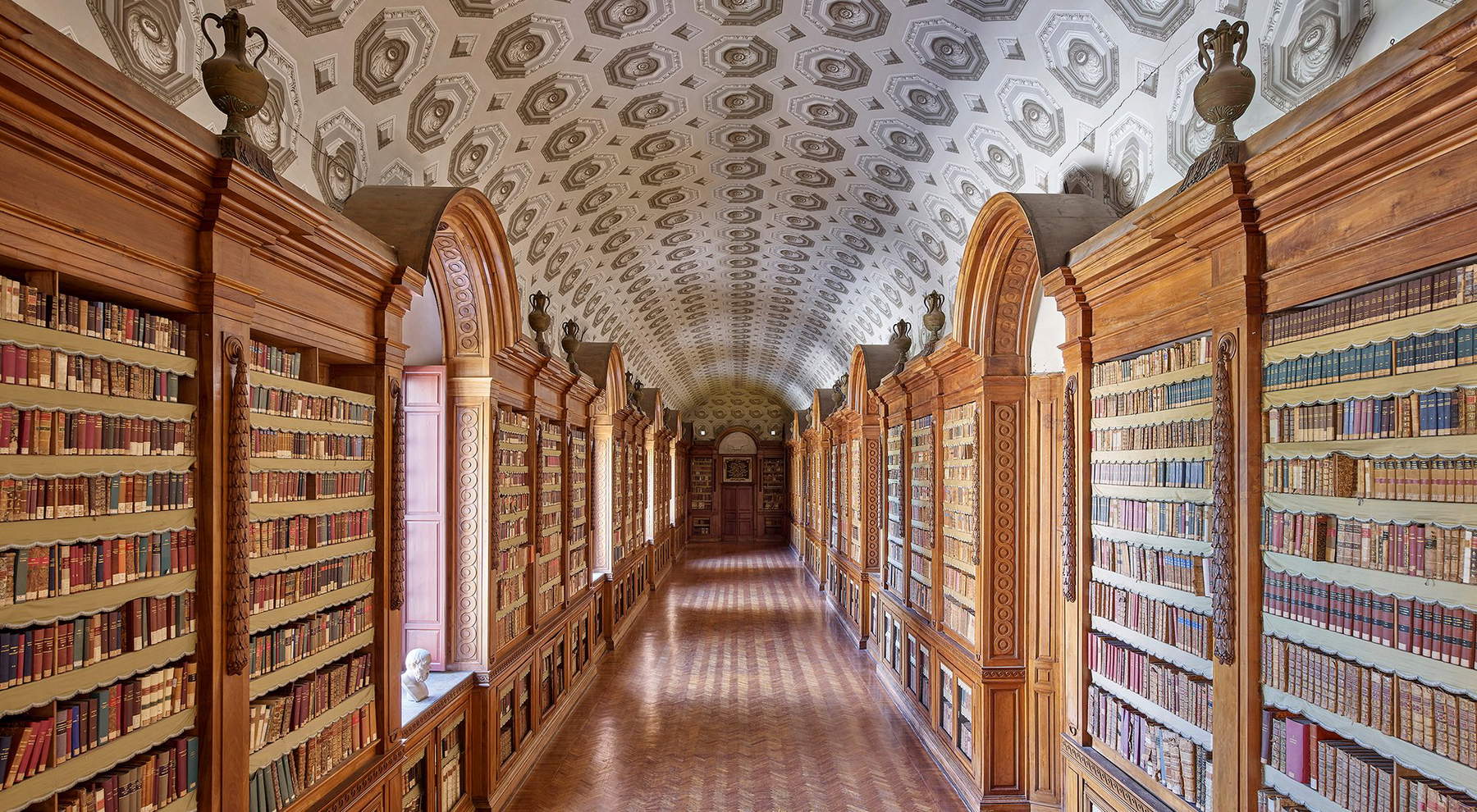

Located in the Complesso della Pilotta, of which it is an integral part (in fact, it is on the second floor of the palace, next to the Teatro Farnese and the Galleria Nazionale di Parma), the Biblioteca Statale Palatina of Parma was founded in 1761 by Filippo di Borbone, duke of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, with the idea of creating an institute to promote education, and then opened to the public in 1769 (the inauguration was attended pertecipecipecip also Joseph II, Austrian emperor and brother-in-law of Ferdinand of Bourbon, who had succeeded his father Philip in 1765). It has a vast library holdings: 700,000 volumes, 6,600 manuscripts, 3,000 incunabula, as well as illuminated codices from the 11th and 12th centuries, and 50000 prints. Among the most precious gems of the holdings is the Fondo Parmense, which contains numerous books and documents on the history of the city but also includes nuclei on other subjects (e.g., the Spanish fund with numerous works from the “Siglo de Oro”), the Fondo Palatino (it was the personal library of the dukes of Bourbon-Parma), the Parmese manuscripts (the fund that includes De Prospectiva Pingendi as well as other outstanding items, such as one of the oldest earliest witnesses to the Divine Comedy), the Palatine manuscripts (including the Atlantic Bible, the 11th-century Greek tetravangel, the Breviary of Barbara of Brandenburg, and French and Flemish books of hours), the De Rossi Collection (one of the world’s most important collections of Hebrew manuscripts and printed books), the cabinet of drawings and prints, and the music section.

At the Palatina in Parma you can also visit the splendid historical spaces: the famous Petitot Gallery, named after the French architect (Ennemond Alexandre Petitot) who designed it at the end of the 18th century, the great Salone Maria Luigia with frescoes by Francesco Scaramuzza, who also painted the decorations of the Dante Room, with themes from the Divine Comedy. The Palatina also preserves numerous works of art. Among them, the most famous is probably the bust of Maria Luigia, reigning duchess from 1814 to 1847, executed by Antonio Canova in 1821, which arrived in Parma the following year (it was placed in the Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts), and became part of the Library in 1875, where it was placed in the reading room dedicated to the sovereign: this is where the marble work can still be admired.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.