On July 31, 1920, four days before his death, Vittore Grubicy de Dragon (Milan, 1851 - 1920) left one of his most important works, the Winter Poem, to Milan (“This work,” we read in his will, “is assigned by me to the municipal collection of my hometown”). And today the eight paintings that make up this extraordinary polyptych are all on display in the path of the Gallery of Modern Art, GAM, set up exactly as the great Divisionist painter intended. Winter in the Mountains (this was the title the artist originally gave to his work) is now known as Winter Poem because it was the artist’s precise intention to create a kind of poetic work: “Just as a poem is divided into cantos, songs, sonnets, so my work instead of in a single canvas is composed of several paintings, grouped in a certain arrangement to concert a whole,” the artist wrote.

These are eight views of landscapes of Lake Maggiore, painted between 1894 and 1897 in Miazzina, near Intra (which today with Pallanza forms the town of Verbania), and changed in arrangement on several occasions until 1911, when Grubicy envisioned their final arrangement. Curiously, Grubicy wrote the list of the eight paintings and instructions on how to display them on the back of another of his paintings, which is not part of the series (it is Sale la nebbia dalla valle, an oil on cardboard from 1895 now in the collections of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome). The notations are part of a handwritten dedication to a person whose name is unfortunately illegible, which was followed by photographs of the paintings: “Dear ... this impression is a detached cue from my work of which I am attaching to you the compositional scheme however poorly the photograph is. Sincerely yours Vittore Grubicy July 19, 1911. / ’Winter at Miazzina. Pantheistic poem in eight pictures 1894-1911 A) Night / B) El crapp di Rogoritt / C) Sinfonia crepuscolare / D) La buona sorgente / E) A sera / F) Tutto candore! / G) Mattino / H) La vallata.” Over time, the paintings were also given slightly different names than those noted by the artist (they were modified by Grubicy himself). The earliest, from 1894, is Night (or Lunar Night, or still Moonlight), followed by two works from 1895(Rogoritt’s El crapp or Sheep on the Cliff, and The Valley or The Valley of the Toce), three from 1896(Twilight Symphony or Twilight Harmony, The Good Spring or The Spring, and In the Evening, or also known as From the Window: Winter Evening, Evening, and Return to the Barn), and finally two from 1897(All Candor! also known as Snow or In albis, and Morning, or Joyful Morning). Grubicy lists them in the way they should be displayed, mentioning first the paintings in the lower row and then those in the upper row.

Winter in the Mountains constitutes a kind of manifesto of Grubicy’s poetics, as is well evidenced by the words “pantheistic poem” that the artist himself had adopted as the subtitle of his cycle. A “secular pantheism” (as art historian Sergio Rebora, a great scholar of Grubicy’s figure, called it) that expresses the artist’s emotion and emotion before the wonder of nature. “A painting,” Grubicy had to write in 1891 in response to some of the criticisms levelled at the Divisionist painters in the aftermath of the First Brera Triennial Exhibition staged that year (it was the first time the Divisionists presented themselves to the public), “is not a work of art if it does not reflect like a mirror the psychological emotion felt by the artist before nature or before his own dream.” Miazzina’s landscapes are thus always mediated by the artist’s feeling, who with his poem calls to mind memories and sensations: they are, in short, among the most interesting Italian masterpieces of the landscape-state-of-mind genre, of which Grubicy was one of the greatest interpreters. When the artist began painting the works in Winter in the Mountains, he had recently left the leadership of his gallery, a point of reference for the Milanese art scene of the time, to his brother Alberto, in order to devote himself better to criticism (he was in fact also an active militant critic) and painting. His intent, Rebora recalled, “perhaps at the beginning not fully felt with full programmatic awareness, was to create a cycle of pure landscape works through a very personal interpretation of Divisionist technique, considered the most congenial tool to express his own aesthetic vision, elaborated on the escort of the philosophical speculation of Felix Fénéon and Jean-Marie Guyau.”

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon’s Winter Poem set up according to his design at the GAM in Milan |

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, Sale la nebbia dalla valle (1895; oil on cardboard, 39.5 x 61.5 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

|

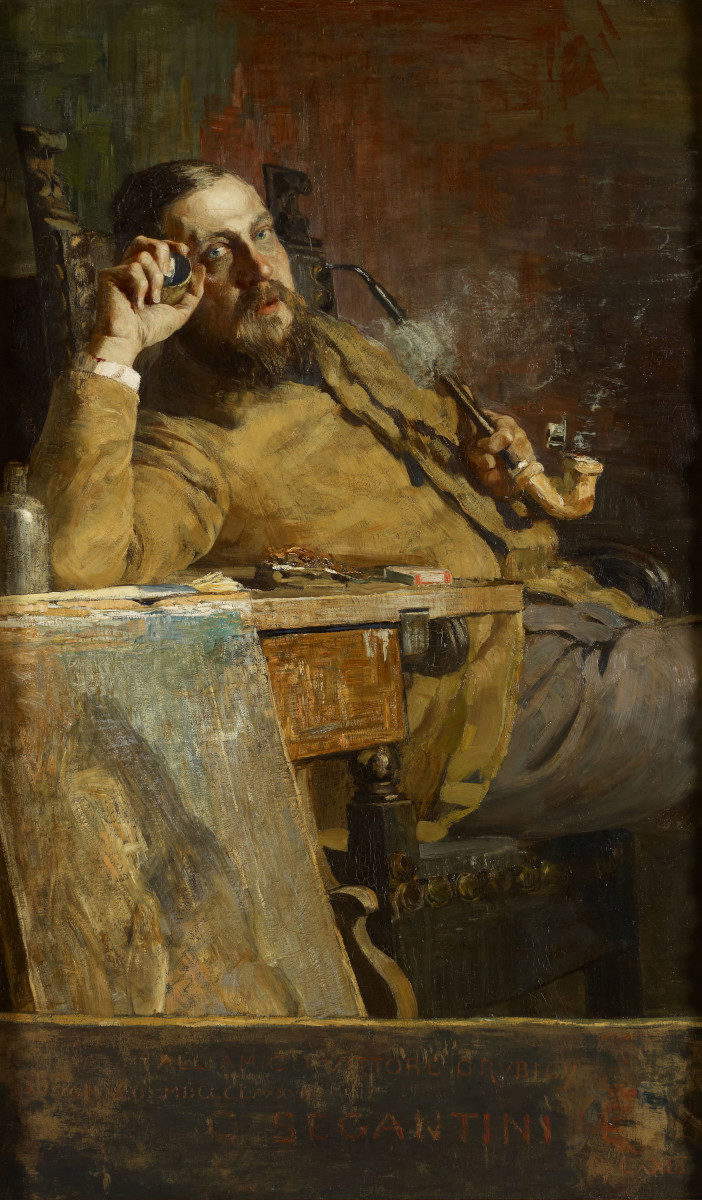

| Giovanni Segantini, Portrait of Vittore Grubicy de Dragon (1887; oil on canvas, 152 x 92 cm; Leipzig, Museum der bildenden Künste) |

Journalist Félix Fénéon (Turin, 1861 - Châtenay-Malabry, 1944), a fundamental theorist of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac’s Neo-Impressionism (he is credited with the invention of the terms “Neo-Impressionism” and “pointillisme”), was one of the main points of reference forGrubicy’s aesthetics, which, thanks to Fénéon’s work, found points of contact with French experiences that started from the concept of color as an optical datum: art historian Annie-Paule Quinsac has found that the articles Grubicy wrote at the turn of the 1880s and 1890s contain punctual takes and quotations (albeit without Fénéon being named) from the French critic’s articles, in particular from three pieces published in the magazine L’Art Moderne to which the Milanese painter was a subscriber, namely Le Neo-Impressionnisme of May 1, 1886, L’impressionnisme aux Tuileries of September 19, 1886, and La Grande Jatte of February 6, 1887. The aesthetic suggestions from which pointillism was to be born were declined according to a particular meaning of landscape-state of mind reread according to the thought of Jean-Marie Guyau (Laval, 1854 Menton, 1888), and in particular according to the idea of art as a means of social achievement and as an engine of solidarity: “One of the requirements of true and enduring art,” Grubicy wrote in an article entitled Landscape and published on August 14, 1892 in La Riforma, “is expansiveness, sociability, and by this requirement it achieves its highest purpose: to bring men closer together, to fraternize them through the commonality of the same stimulus that excites in varying degrees the sensitive functions, producing a collective, social aesthetic emotion.” The trait d ’union that brings these instances together, Rebora wrote again, is the “concept of suggestion, as it was defined by Paul Souriau: a kind of synaesthesia that associated images and sensations with each other through time.” And the desire to give rise to synaesthesia was often emphasized by Grubicy in the texts accompanying exhibitions of his paintings, when he referred to the paintings as “symphonies.”

To achieve this goal it was necessary not only to devote himself almost exclusively to painting (in fact, from 1892 Grubicy would also very conspicuously curb his critical activity), but also to resort to a sojourn in a place where total immersion in nature was possible, outside the bustling rhythms of the city, where life was still regulated by the times dictated by nature, far from factories and industries, bourgeois life, worldliness and the very circles of art, the conditioning of everyday city life, and urban frenzy. For six years, from 1892 to 1898, the small hamlet of Miazzina, a village of shepherds and peasants on the heights of Lake Maggiore, thus became his retreat, the place where he could completely abstract himself from the world, arriving at that coveted isolation that constituted a necessary condition for enacting the poetic program that the artist set himself. A number of landscapes were born here, most of them painted in the quiet of the winter season, which are now preserved in various museums: the eight that make upWinter in the Mountains or Winter Poem are among the most intense and refined, and are among the pinnacles of Grubicy’s landscape painting, works in which the artist’s identification with nature, in a kind of calm and moved panism, reaches its highest fulfillment. These are landscapes painted with intense emotional accents: the artist studies at length the effects of the light that rests among the trees in the woods, on the snow, on the waters of Lake Maggiore, to create works that give us back excerpts of lake views at certain times of the day, when the light conditions reach their maximum symbolic and evocative potential. They are, quoting Rebora again, “emotional revisitations” of the natural datum, executed starting from a study from life (or with an initial drafting of color directly on site, even simply to divide the lights from the shadows), and then finished in the studio: the artist, moreover, proved to intervene on his paintings even several years later.

Rebora also noted a consonance with the poetry of Giovanni Pascoli (San Mauro di Romagna, 1855 Bologna, 1912), and in particular with the Pascoli of Myricae. There are, meanwhile, biographical similarities: as Grubicy had sought refuge in Miazzina, so Pascoli had done in Castelvecchio. Similarities are then to be found in the similar way of relating to the existing: “The symbolic value identified in the elements of nature, the sense of expectation and mystery hidden the sense of expectation and mystery hidden in the small things of everyday life, the juxtaposition of auditory and visual images, the effects of synesthesia seem to find themselves in the respective inner worlds of the artist and the poet.”

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, Lunar Night or Moonlight (1894; oil on canvas, 64.5 x 55.5 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1717) |

|

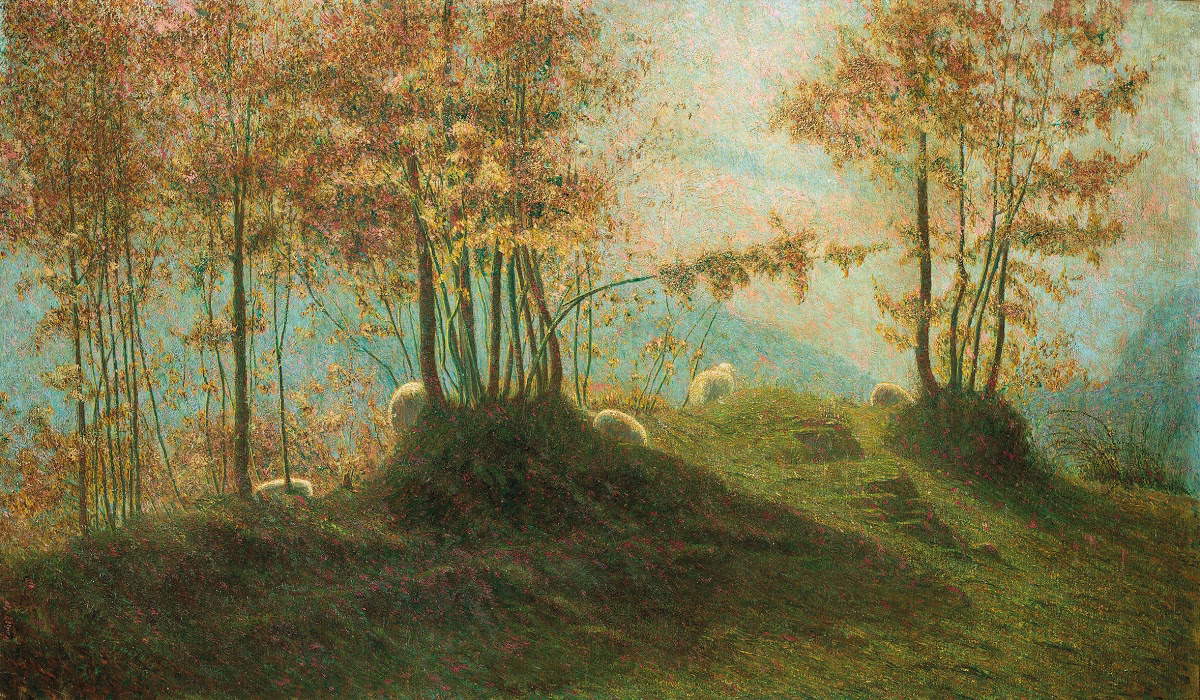

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, El crapp di Rogoritt or Sheep on the Rock (1895; oil on canvas, 58 x 98 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1720) |

|

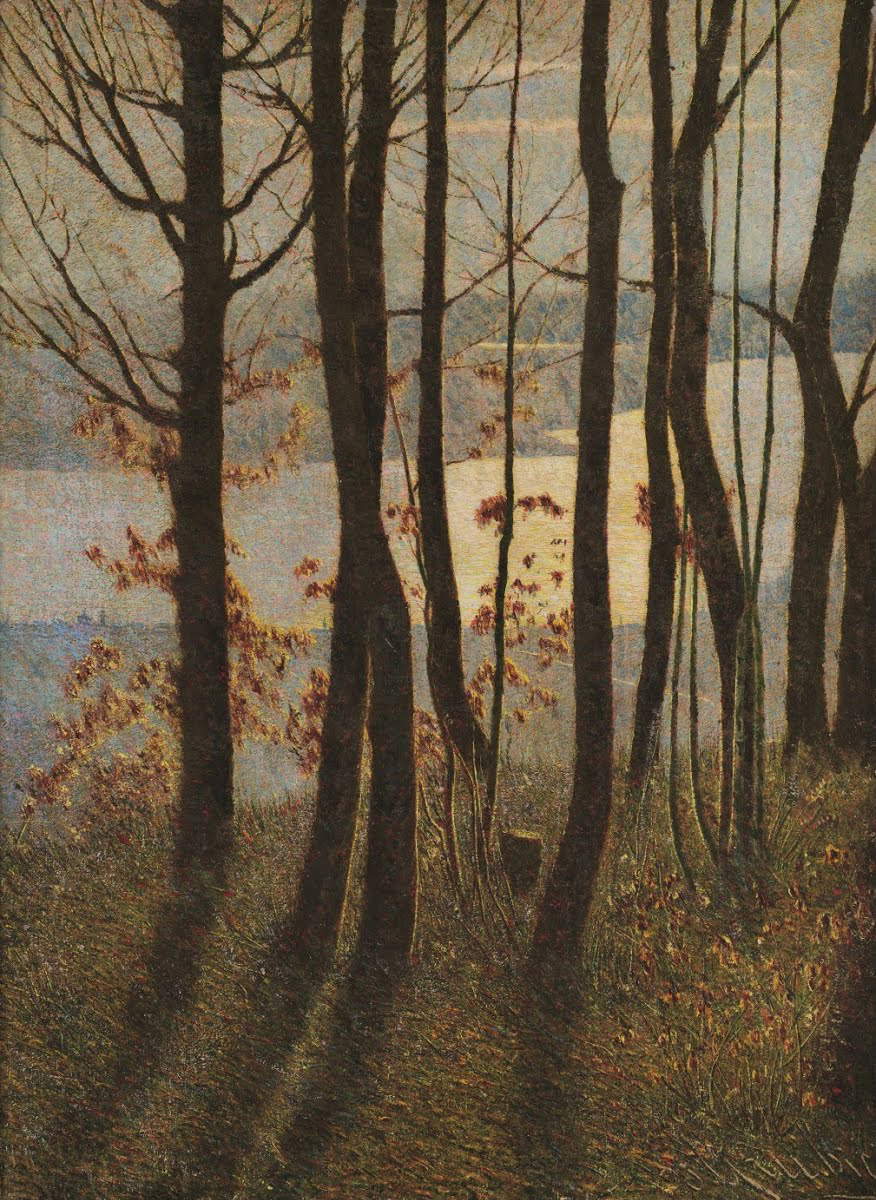

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, Sinfonia cre puscolare or Twilight Harmony (1896; oil on canvas, 66 x 55.5 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1716) |

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, La sorgente or The Good Spring (1896; oil on canvas, 57 x 99 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1722) |

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, From the Window: Winter Evening or The Evening or Return to the Barn or In the Evening (1896; oil on canvas, 66 x 55.5 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1715) |

The choice of the winter season at the expense of others probably responds to the artist’s sentimental inclinations, but also to aesthetic reasons: the winter landscapes of the Alps above Lake Maggiore, with their bare nature, with the winter color palette reduced to a minimum, allow the artist not to get lost in descriptive minutiae, enthusiastic outbursts or narrative distractions, and on the contrary allow him to concentrate on his aesthetic goals. “Placing my forehead on the cold glass of my window,” the artist wrote to Miazzina on Feb. 3, 1895 in a letter, “I went meditating with sadness on the innumerable miseries of all sorts that swarm ceaselessly down there under that sea of fog, that funereal sheet covering the plain while the mountain hovered serene in the clear and pure lunar night.” And it is, the one described in the letter, a vision similar to the one we find depicted in the first painting of the cycle, Notte (or Moonlight: this is the title found on the frame of the painting, and it is the artist himself who often refers to his works with slightly different titles, which is why they are found with multiple titling in the catalogs): a view of the lake caught from the heights of Miazzina. The light of the moon reflecting on the lake accompanies us toward the village of Intra, which stands out against the light (we also see the profile of the church of San Vittore) on the banks, and our gaze is also drawn to the lake by the profiles of the trees that the artist inserts in the center of the composition and that almost invite us to look beyond their branches, among the leaves, to catch a glimpse of the outline of the town between the two rivers, whose waters are also enhanced by the moonlight. Quite another atmosphere, however, is what we find in Rogoritt’s El crapp, which shows us some grazing sheep (the work was in fact also exhibited at the time under the title Sheep on the Cliff) in the grazing light of twilight, among birch and beech trees, in a piece of landscape taken toward the mountains of the Strona valley. The work, interestingly, is dedicated to Anna Kuliscioff, who was among the founders of the Italian Socialist Party.

Also set in the atmosphere of sunset is Sinfonia crepuscolare (Twilight Symphony), which captivates us with the powerful backlighting that envelops this piece of the Toce valley, toward Mount Mottarone, which we see partly on the left. La buona sorgente, a horizontal format canvas, takes us to an idyllic, silent beech forest in the middle of which water flows, as per the title, from a spring: the delicacy with which Grubicy restores this passage of landscape to the viewer, with pure colors lightly juxtaposed as if to suggest, synaesthetically, the gentle rush of water flowing through the forest, makes La buona sorgente one of the most intensely lyrical paintings in the entire Winter Poem. It continues with A sera, a work exhibited under different titles, which closes the lower part of the “polyptych”: the view is the same as that of Notte and Sinfonia crepuscolare, though more shifted southward (here we can also see Lake Varese, the village of Laveno and Lake Comabbio in the distance). The time of day changes: this time the Toce Valley is depicted in the tranquility of evening falling over the mountains. On one of the occasions it was exhibited, the work was presented under the title From the window: winter evening. Given the viewpoint, however, it seems unlikely that Grubicy painted from the window of his house: more plausible that he was outdoors.

Moving on to the upper part of the Pantheistic Poem, comes the only painting in which snow is the protagonist, namely All Whiteness!, where the winter light reaches one of the highest peaks of poetry in the entire cycle: enhanced by the Whiteness of the snow, the light rests on the reddish leaves of the trees and tinges the mountains with rosy hues and the waters of the lake with orange. The subsequent Morning also glows with auroral light reflections that rest gently on the water, tinging it pink. Moreover, with the paratactic arrangement of the trees obstructing the view of the lake, here Grubicy probably demonstrates his closest point of proximity to the Japanese prints that constituted an important source of inspiration for him: from the time of its opening to the public in 1876, the Grubicy Gallery had been selling objects of Japanese and Oriental provenance in general, reasoning that Vittore Grubicy was very familiar with Japanese art. The tree branches that stand between the artist and the object of the view are inferred from Japanese art, and the same could be said of the almost pure masses of color that characterize this painting. The painting with which Grubicy bids farewell to the viewer, The Valley, takes us to a mountain path that leads down the slopes of the Toce Valley.

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, Tutto candore! o Neve o In Albis (1897; oil on canvas, 58 x 97.5 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1719) |

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, Mattino o Mattino gioioso (1897; oil on canvas, 75 x 56 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1718) |

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, The Valley of the Toce or The Valley (1895; oil on canvas, 58 x 98.5 cm; Milan, GAM, inv. 1721) |

Vittore Grubicy de Dragon had the opportunity to exhibit the paintings of the cycle several times, often separately, or combined in triptychs: at the 1897 Venice Biennale, for example, he brought a triptych, Winter in Miazzina, of which La sorgente, Sera and Meriggio were part; at the 1899 Biennale he presented for the first time a triptych with the title Inverno in montagna, and other works he would bring in 1901, always also combining them with paintings that today are not part of the definitive arrangement of the cycle, the one we see at the GAM in Milan. And his works were generally appreciated. “Grubicy presents us with a triptych,” wrote the critic Mario Morasso in his review of the 1899 Venice Biennale, published in the Nuova Antologia, “which far surpasses his earlier works, in which one observedu no massive squandering of effort, a kind of assiduous scraping without purpose. Now, on the other hand, the goal is almost reached, the three landscapes are of a vivid and brilliant transparency and luminosity; the effort disappears in the complete fusion of colors as sharp and fresh as morning flowers. In the center a few large trees soar against a delicate pinkish blue sky that clears far away. Amidst a mass of pure and crystalline air in the left panel some twigs of yellow mountain flowers stand out against the snowy ground with a radiant clarity while in the background the rosy blue cloister of the mountains is drawn ; the same motif, without the white effect of the snow, is repeated on the right; and the overall impression is limpid and most effective , for the feeling of the landscape finds a living revelation in that rapid and crystalline composing and recomposing of light in its elements.”

It was finally 1911 when, at the first exhibition of the Association of Lombard Watercolorists, Grubicy presented the polyptych in its eight-canvas redaction.Winter in the Mountains also represents Grubicy’s last major work (as well as his best-known masterpiece), not least because in the late 1990s the painter was struck by some serious nervous system disorders that led him to give up painting new paintings altogether since 1900: in the last two decades of his career, Grubicy devoted himself rather to acting on his earlier production and exhibiting it to make it known. And today we can consider Vittore Grubicy’s cycle as one of the most important achievements of late 19th-century Italian painting.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.