For a long time the scientific community has been wondering about the identity of the lady depicted in the Portrait of a Lady in Red, one of the masterpieces of the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. But it has also long wondered about the identity of the artist who painted it, wavering between Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci; Pontorme di Empoli, 1494 - Florence, 1557), and his best pupil, Bronzino (Agnolo Tori; Florence, 1503 - 1572), although the latest orientations have led scholars toward Bronzino, with significant margins of safety. It is one of the best-known portraits of Mannerism: it depicts an elegant lady, belonging, as can be inferred from her clothing, to an upper-class Florentine family. Scholar Philippe Costamagna, one of Bronzino’s leading experts, thought to identify, in the image of the effigy, a portrait of Francesca Salviati (Florence, c. 1504 - 1572), the daughter of Jacopo Salviati and Lucrezia de’ Medici, the latter the eldest daughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent: Francesca Salviati was thus the granddaughter of the lord who had ruled the fortunes of Florence in the late 15th century, although she was born several years after her grandfather’s death. She was also sister of Maria Salviati, mother of the future Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici and wife of Giovanni dalle Bande Nere. Francesca was, in short, an important woman of the Medici household, and in 1533 she married Ottaviano de’ Medici, who moreover was a commissioner of Pontormo. According to Costamagna, this painting may have been made on the very occasion of her marriage, although there is no record of it ever passing through the Medici collections.

Certainly, if we assume that the painting had to pass through their collections, it had already left them in 1612, when it is recorded in the inventories of the Riccardi, as a portrait of a lady with a small dog, executed by Pontormo, without any further specification about the subject or its ancient provenance (“A portrait of similar height by the hand of Jac.o da Puntormo, inside a woman with a small cannon, and with gilt ornamentation”). On what basis was the identification with Francesca Salviati proposed? The prevailing colors of the clothing, white and red, are those of the family’s coat of arms, although, Costamagna pointed out, the colors of the robes do not necessarily play a role related to heraldry (not to mention, then, that red and white are also the colors of other families, for example, the Cybo): more revealing, if anything, is thediamond ring that the lady wears on her right hand, of Medici fashion, inserted probably to mark the lady’s lineage, or her belonging to a family allied with the Medici. However, it is quite evident, the scholar wrote, that the painting “already has the characteristics of the state portrait, both in its monumentality and as an allegory of the genealogical aspirations of a branch of the family.” And it is, arguably, the “first female portrait painted in Florence with all the characteristics of the court portrait,” if we admit that Bronzino executed it at aboutabout 1532, or at any rate after his return from his stay in Pesaro (according to scholars such as Alessandro Cecchi, Antonio Natali and Angelo Maria Monaco, it may instead have been executed during his stay in the Marche, and consequently the lady could be some lady of the court of Urbino, but there are also those who, like Gabrielle Langdon, even anticipate the work to the 1920s). There are also those who have proposed other identifications: for example, some scholars have suggested seeing in the Portrait of a Lady in Red the effigy of Maria Salviati, Francesca’s sister, on the basis of physiognomic comparisons with other known portraits of the woman, such as those by Pontormo preserved in Baltimore and the Uffizi, although there is one argument that poses a serious obstacle. Mary was in fact widowed in 1526, and the attire she sports in Bronzino’s portrait is wholly inappropriate for a woman who had lost her husband (widows were in fact portrayed in black robes). The problem would be solved by anticipating the dating, but such an early execution, though supported by some critics, poses problems of comparisons with other works: there would be no works before 1526 that could be convincingly juxtaposed with the Städel painting.

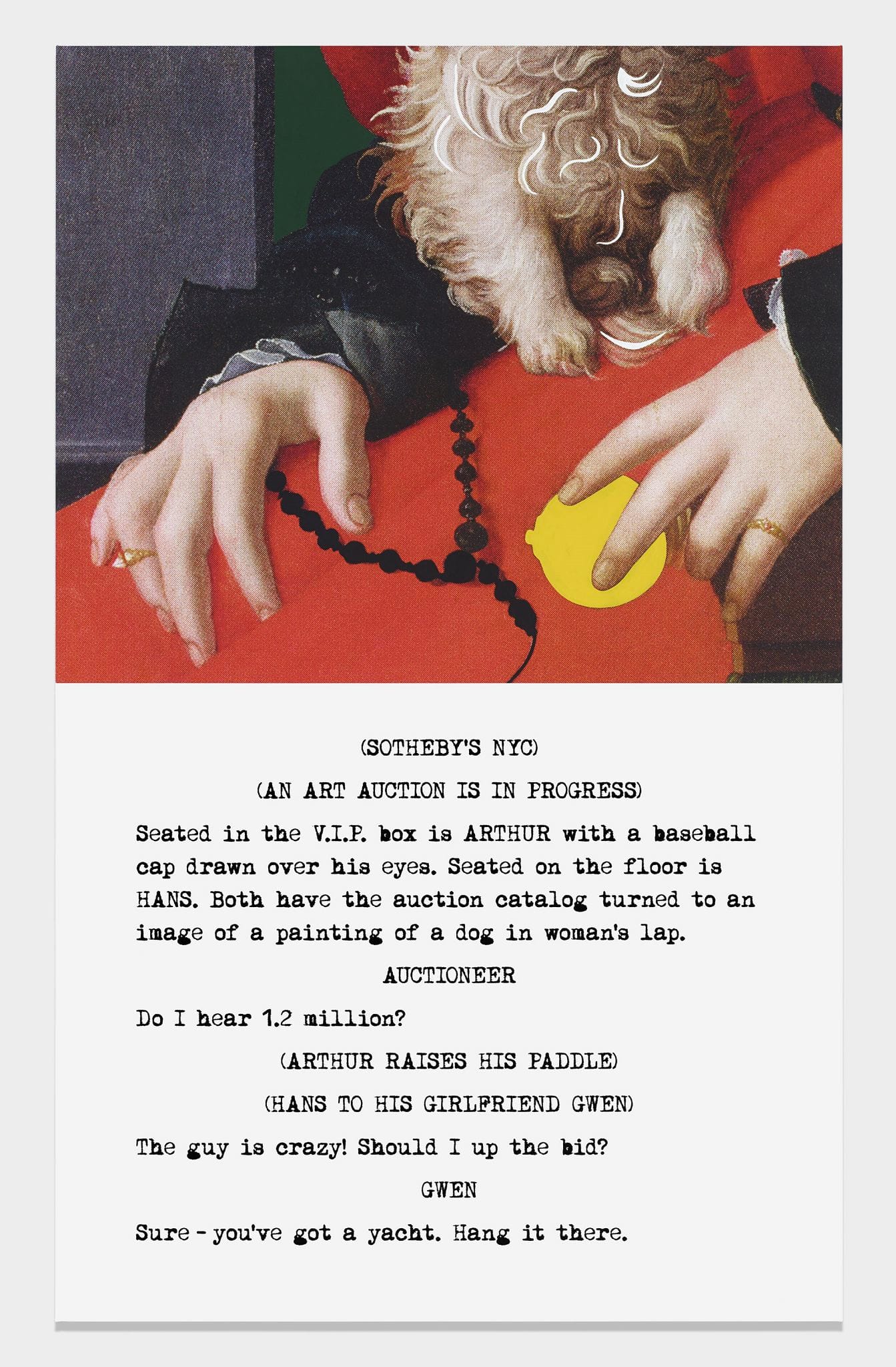

Elegant, sophisticated, swathed in her rutilant red gown covering her snow-white blouse, and with her small dog sitting, docile, on her lap, Bronzino’s lady embodies the quintessence of the most up-to-date portraiture of sixteenth-century Florence. The feature that stands out most are the bright, contrasting colors, beginning with the cinnabar of the robe that almost violently clashes with the dark blue of the sleeves and the bottle green of the armchair, a savonarola, on which the lady sits (an armchair, moreover, decorated with a gilded mask that highlights the taste for the bizarre and grotesque typical of Mannerism: it is, moreover, a decoration very close to that which appears in Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man preserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, one of the paintings which, in terms of color rendering, atmosphere and general impression most closely resembles the work in the Städel Museum). Under this element, moreover, we see a handle that takes the form of two dolphins clutching a ball between their mouths: since the ball was a symbol of the Medici, it is believed that this decorative detail may be a further reference to the family that dominated 16th-century Florence. And, speaking of symbolic elements, Gabrielle Langdon’s reading of the chair’s knob is certainly curious: a reference to the golden apple of Venus to convey the image of the young woman, the young wife, as that of a Venus who guards all the virtues of love. But in addition to the profane, there is also the sacred: in fact, the lady holds a rosary in her right hand, a symbol of her devotion. In any case, that this is the image of a married woman is then made further evident by the presence of the dog, a clear symbol of marital fidelity. The animal, it has been observed by Stefano Zuffi, is a spaniel, a small dog that appears in so many coeval portraits, for example, Titian’s Portrait of Eleonora Gonzaga Della Rovere from 1537, or the Portrait of Clarice Strozzi from 1542, and we even see it in Titian’s Venus of Urbino , a sign that the spaniel breed must have been particularly fashionable in those years.

And that this is a Bronzino painting has been largely argued on stylistic grounds: we can say that we find ourselves here at the beginnings of Bronzino’s portraiture, at a stage when the artist, then in his early thirties or so, is still linked to the master (hence the traditional attribution to Pontormo), but is already well on the way to elaborating his algid, detached, almost abstract portraiture, yet capable ofoffer the subject an unparalleled precision, tactile sensations hardly found in the production of other portrait painters of the time, and above all capable of conveying, more than an image of the effigy, the idea of what the subject represents. Bronzino’s portraits are essentially official portraits, portraits of power, portraits that indicate status, belonging, or a place in a network of relationships. Bronzino, with his lady in red, is still working out the model: the expression, in fact, is not yet the glacial one of the Portrait of Lucrezia Panciatichi, since a motion of humanity is still noticeable in the expression of the presumed Francesca Salviati, whose mouth seems almost to hint at a smile, and the volumes are not the almost geometric ones that distinguish the highly sophisticated portrait of about 1541 now in the Uffizi. The path, however, is already marked out.

The

The

Already in this portrait, however, one glimpses all that perfection in the rendering of details that has led many scholars, at least since Charles McCorquodale in 1981 (the first to speak with conviction of a bronze autograph for this painting), to rule out attribution to Pontormo. Other elements then point back to his young pupil, beginning with the lady’s evasive gaze , and that finesse of description that is especially noticeable in the decorations: observe therefore the jewels, the gaze, but also other elements such as the folds of the shirt, the hair of the little dog, or the net that holds the hair in place. Such accuracy is hardly found in the paintings of Pontormo, who never lingered in descriptive minutiae. For the sake of comparison, one could call into question the Portrait of a Young Man in the Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Mansi in Lucca, a work the Empolese painted roughly between 1525 and 1530, or one could look at theHalberdier in the Getty Museum: one will notice, especially in the former, a more cursive and relaxed painting, while in theHalberdier, which is perhaps as close as Pontormesque comes to the Portrait of a Lady in Red, the rendering of certain details (such as the hilt of the sword or the gold chain the character wears) does not match the lenticular quality of that of the Frankfurt Lady. Conversely, the rendering of the details of the gold pieces recalls that of the Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo in the Uffizi, Bronzino’s masterpiece of portraiture, while the reflection of the lady’s fingers on the pommel of the chair, a virtuoso finesse, is the same as that found on the helmet of the Portrait of Cosimo I: in the latter painting, too, the virtuosic piece of fingers projecting their image onto the metal is noticeable. Everything, in short, leads back to Bronzino’s finer portraits.

The iconographic elements of Bronzino’s painting, and even the lady’s pose itself, actually help to suggest to the viewer a pervading sense of nobility of spirit, of outer but also inner beauty: it is also necessary to note, in addition to the elements that underscore the virtues of the lady, of which we have mentioned above, the presence of the books resting on the pietra serena bench at the foot of the niche that serves as an architectural backdrop to the lady, to heighten the sense of distance. The books are symbolic of her love of letters. The scholar Angelo Maria Monaco has moreover identified the books as further support for the attribution to Bronzino, since books painted in the same way, that is, depicted close to the effigy (and not in his hands, as was more often the case), also appear in some portraits painted by the Florentine artist between 1533 and 1545.

In the early nineteenth century, the painting was on the Florentine market, and it passed through several private collections until, in 1882, it was purchased by the Frankfurt Kunstverein , and has remained in the German city ever since. And it was here that the Portrait of a Lady in Red was paid homage by one of the most important artists of the second half of the 20th century, John Baldessari (National City, 1931 - Los Angeles, 2020). In fact, the area of the painting where the woman’s hands and dog’s paws are located became the subject of a work by Baldessari, Movie Scripts / Art: Hang in There, from 2014, where the detail of the work appears along with a text written in typewriter font, resembling a movie script (this, moreover, is the translation of “movie script”), which tells of a fictitious auction at Sotheby’s in New York attended by two characters, Arthur and Hans, who are looking at the sale catalog at the very spot where the detail of the painting is located. The auctioneer asks if there are any bids of 1.2 million, Arthur raises his paddle, Hans turns to his girlfriend Gwen saying, referring to Arthur, that “that guy is crazy,” and asking her if she should raise, and Gwen replies, “sure, you have a yacht, you have to hang it there.”

Baldessari started from the works at the Städel Museum, including Portrait of a Lady in Red, to probe the relationship between painting and photography and between image and language, making provocative, ironic, irreverent works that take a critical viewpoint on the institutions that preserve art, on the mechanisms that regulate this world, but also on the way we ourselves look at art. Baldessari’s work reminds us, after all, that that painting that we admire today hanging on the wall of a museum, and toward which we perhaps approach with a certain, respectful deference, in ancient times almost certainly adorned the home of a wealthy personage of the time, a personage who today would have no problem offering more than a million dollars to buy a museum painting in order to allocate it to his yacht. The distance in time perhaps makes it hard for us to think about it, but contemporary art has reminded us what a portrait by one of the greatest artists of the time could be used for: to emphasize a status, a belonging. And Bronzino’s lady was much more material than it might appear.... !

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.