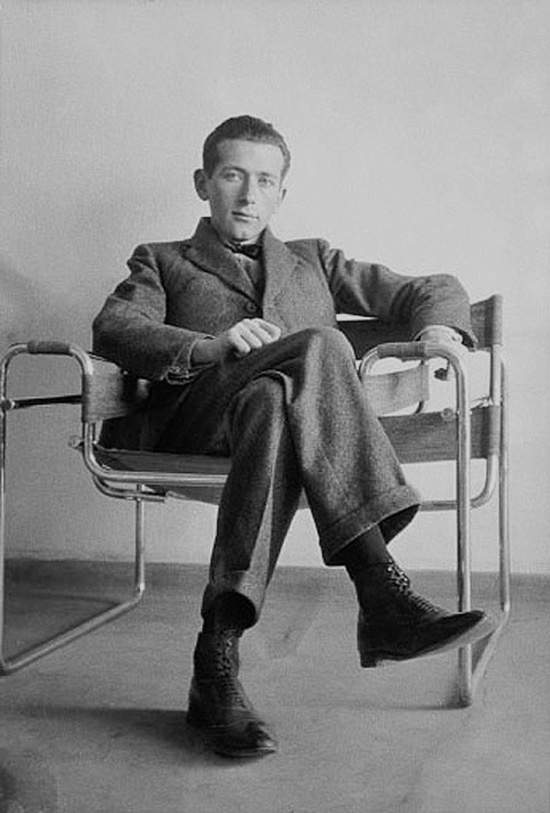

When the Bauhaus architects approached the design of everyday objects, such as tables, chairs, lamps and the like, the guiding principle that inspired them was that of functionalism: they always started from an analysis of the user’s basic needs, and created an object whose aesthetics were considered a consequence of its functions of use. Thus was also born the Wassily (or Vasily) Chair , the masterpiece of Marcel Breuer (Pécs, 1902 - New York, 1981), one of the design symbols of the Bauhaus movement.

Few objects in the history of design have managed to capture the essence of innovation and elegance like the famous Wassily Chair. Indeed: it could be said that the Hungarian architect and designer’s creation revolutionized his field, with a chair that not only embodied the Bauhaus ideal and method (innovation through functionality, practicality, use of unusual materials, essential lines), but also constituted a “typological leap,” as scholar Dario Russo has written, since “unlike the traditional four-legged wooden chair, it features a tubular metal frame that, without rear legs, allows comfortable swinging” while also entailing “a number of advantages: Technical-productive, economic, hygienic and aesthetic.”

Also known as Model B3, it was designed in 1925 by Breuer, then director of the wood workshop at the Bauhaus school in Dessau. The name “Wassily” refers to the famous Russian painter Vasily Kandinsky, but contrary to popular belief the name by which the chair is commonly known today was not invented by Breuer, nor was it a gimmick of the time when the object was designed. In fact, the name Wassily dates back to the 1960s, when entrepreneur and designer Dino Gavina (San Giovanni in Persiceto, 1922 - Bologna, 2007), the owner of Gavina SpA, which had put the chair back into production after meeting Breuer in New York, learned that Kandinsky (Breuer’s friend and mentor), at the time of the first design, had asked to receive the first example of the new chair for the hall of his apartment.

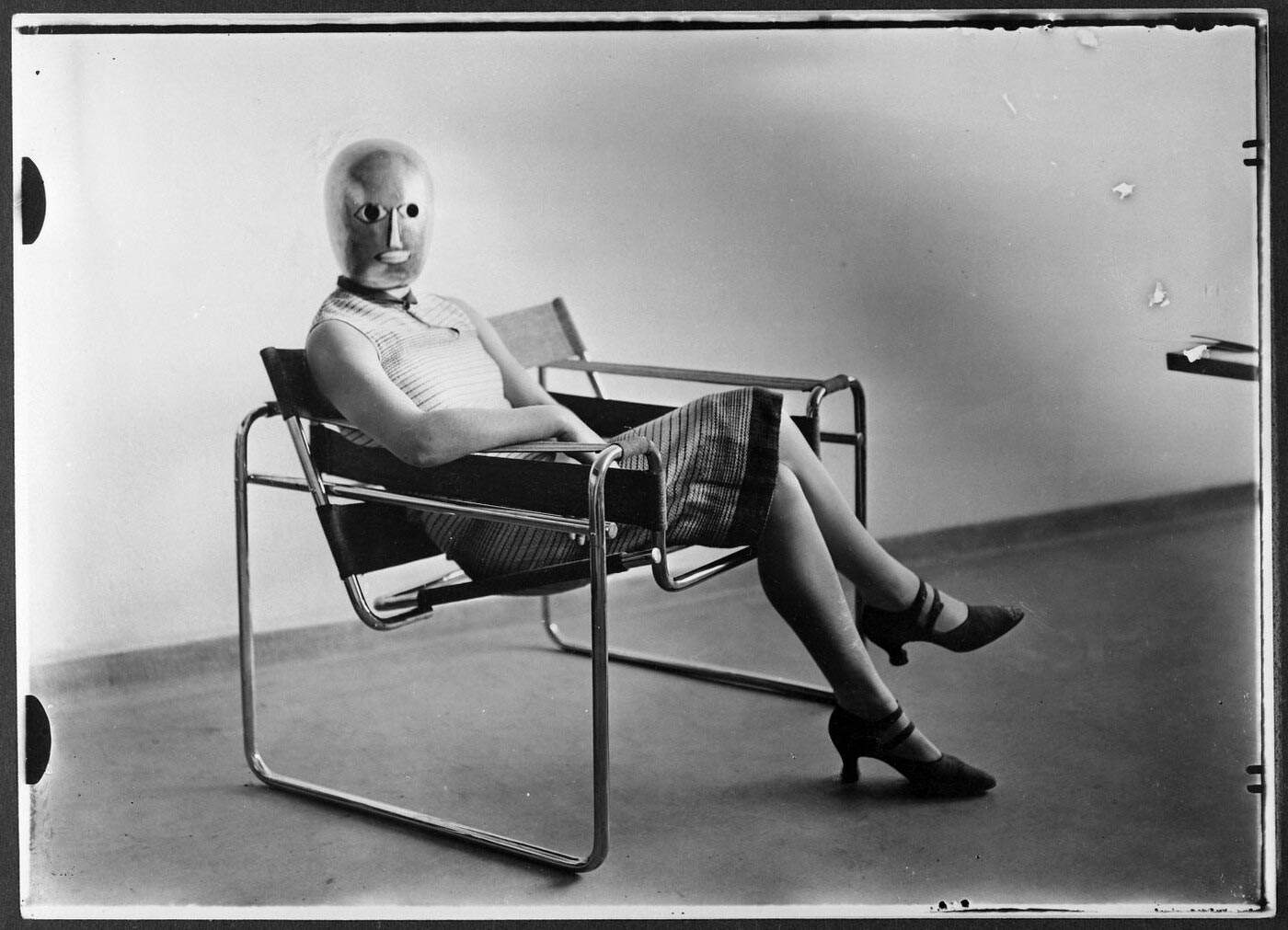

The original chair, after having been used as early as 1926 to furnish the lecture hall of the Bauhaus in Dessau, was put into production in the late 1920s by Breuer himself, who had founded a company called Standard Möbel, later absorbed by the Austrian furniture manufacturer Thonet(editions of the first chair are very rare today), and at that time the name of the object was indeed Model B3. Breuer envisioned a chair made of chrome-plated steel tubing and a fabric called Eisengarn (“iron yarn”), a very durable and shiny-looking waxed cotton thread invented in the late nineteenth century, then further developed in the Bauhaus workshops thanks largely to the input of one of Breuer’s students, Margaretha Reichardt, an artist and weaver.

One of the most distinctive features of the Wassily chair is precisely its pioneering use of steel tubing. Marcel Breuer experimented with the use of bent chrome-plated steel tubing (20 millimeters in diameter) to create the chair’s frame: an approach that, inspired by bicycle frames (Breuer, who often rode bicycles, had had the idea of employing steel tubing realizing its lightness and versatility), not only made it incredibly light, but also gave it a modern, industrial aesthetic.

Initially, Breuer thought of involving the Adler company, which manufactured bicycles, in his project, but he was unsuccessful. He then turned to the Mannesmann steel mills, which had invented a seamless steel tube produced in the late 19th century-a material that could be bent and reshaped without losing much of its strength. There was another advantage, explained Robert McCarter, author of a monograph on Breuer. “As all good bike enthusiasts know, steel-framed bikes are not only strong, they are also relatively springy and have the merit of absorbing vibration much better than their aluminum counterparts; Marcel learned to exploit this in new ways. Breuer bought 2-centimeter diameter tubes (corresponding to the size of his bicycle), pre-bent them to his specifications, then hired a plumber to help him weld the steel tubes together to make furniture frames. The first design using bent tubular steel was given the name ’B3,’ a numbering system that Breuer would use for all his furniture in later years. This was an armchair, the first version made with nickel-plated steel tubing welded to form a rigid frame with four vertical legs that bent and then lowered to support the seat and back, both inclined steel frames, on which it was stretched. Breuer found this version too rigid, lacking the resilience or flexibility he felt was necessary for the comfort of the occupant, and he modified and refined the design to arrive at what he considered the ’definitive’ version, also dated 1925; in fact, Breuer continued to refine the design of the armchair until early 1928, when he arrived at the version we know today.”

Breuer’s genius, as McCarter explains, lay in the way he combined the properties of the tube, namely its strength, elasticity, and the way the tubes could be slotted together, rather than welded (a feature that gives the chair greater flexibility when someone sits on it: a structure with welded joints is much stiffer, on the other hand), with a recognizable shape, to give much greater feelings of comfort than one would expect from an abstract shape like the Wassily chair. Plus it was very light and easy to transport.

![Marcel Breuer, Model B3 (1925 [c. 1927-1928]; chromed tubular steel and natural canvas, 73 x 82.2 x 74.3 cm; New York, Brooklyn Museum) Marcel Breuer, Model B3 (1925 [c. 1927-1928]; chromed tubular steel and natural canvas, 73 x 82.2 x 74.3 cm; New York, Brooklyn Museum)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2023/2409/sedia-wassily-brooklyn-museum.jpg)

The chair follows the principle of frame construction, in which steel tubes form the main frame. This frame structure not only provides stability, but also allows for the creation of those distinctive curved and flowing shapes that characterize the chair. The finishing details then give the chair a clean, contemporary look. The simplicity of the design is a key element of its modernist aesthetic. The look was also totally new: it was inspired by the celebrated Red and Blue Chair by Gerrit Rietveld (Utrecht, 1888 - 1964), the leading designer of neo-plasticism, while placing itself in a much more modern and innovative way towards comfort, practicality of use, and functionality. “The B3 chair,” wrote architect and scholar John Poros, "perfected the ideas initiated by the Red and Blue Chair. Now, instead of wood, there was a smaller, lighter, brighter chrome-plated steel frame that supported the even lighter fabric seat. The chair becomes more ethereal but still defines the cube of space of a traditional chair, using lines and planes. In addition, the comfort of the chair is enhanced by the sloping line of the seat and back.“ Also notable is the historical significance: ”Breuer’s move to explore modern technologies with tubular steel would have enormous influence on his future architectures. With the Wassily chair, Breuer decreed the end of the craft phase of the Bauhaus in favor of industrial, technology-focused production."

This design challenged the conventions of the time, in which wood was the dominant material in furniture, paving the way for new possibilities of artistic and functional expression. Marcel Breuer had succeeded in bringing to life a true symphony of steel tubing and fabric in the creation of the Wassily Chair, a hymn to the harmony between form and function. A tangible testimony to how a designer can redefine the boundaries of the possible, opening new horizons in furniture design. Bold lines that tell the story of a transformative period, where art merges with functionality. A fragment of art history in the form of an everyday object, a tangible embodiment of the evolution of design toward simplicity and elegance. A beacon of innovation that illuminated the path to a modern aesthetic. All this represented the Wassily chair: its fusion of geometric shapes, industrial materials, and care for ergonomics represented a turning point in the approach to the design of everyday objects. This chair became a symbol of the modernist movement, which sought to unite art, design, and industry into one harmonious vision. Breuer considered it his most extreme work, the “least artistic, least logical, the least ’comfortable’ and the most mechanical.” But it was also the most influential and well-known.

Initially little considered, the Wassily chair became a widely consumed object (we have all sat on a Wassily chair a few times) starting in the 1960s: it was 1962 when Dino Gavina obtained a license from Breuer to start a new production. Then, in 1968, when Gavina SpA was acquired by Knoll, a well-known U.S. design company founded in 1938, the chair’s success became planetary. Even today, Knoll still produces the Wassily chair, although it has replaced the fabric strap with a leather seat, and has made the item available in different color versions (originally, however, the Wassily chair was only black, although when it was marketed different colors were also experimented with). It can be purchased on the official website of the American company (the price is not the cheapest: you need to pay more than three thousand dollars to take home a piece of design history), or in specialized designer furniture stores, even at art galleries that deal in design, not to mention high-quality furniture websites, or again, for those who want to try to save some money, it may be an idea to search among the many design auctions , keeping in mind, however, that prices can vary widely depending on rarity, print run, edition, and condition (in which case one must obtain detailed information about the piece, such as its history, authenticity, condition, and provenance: buying a design piece such as the Wassily chair requires care and caution to ensure that you are getting an authentic, high-quality product).

Incidentally, in an interview he gave just for Knoll, Breuer himself explained how he came to experiment with bent tubular steel while at the Bauhaus: “At that time,” he recounted, “I was quite idealistic. 23 years old. I befriended a young architect and bought my first bicycle. I learned to ride a bicycle and I talked to this young man and told him that the bicycle seems to be a perfect production because it hasn’t changed in the last twenty, thirty years. It is still the original shape of the bicycle. He said, ’Have you ever seen how they make those parts? How they bend those handlebars? You’d be interested because they bend those steel tubes like macaroni.’ That somehow stayed in my mind. So the first chair was born... I realized that the bending had to go further. It should just be bent without welding points so that it could also be chromed into several parts and assembled. Thus the first Wassily chair was born. I myself was a little afraid of criticism. So I had not told anyone that I was doing these experiments. Kandinsky, who happened to come to my studio when the first chair was brought in, said, ’What is this?’ He was very interested, and the Bauhaus group itself was also very interested. A year later, I had furnished the entire Bauhaus with this furniture.”

Even today, the legacy of this object is reflected in its lasting impact on contemporary design. Many variations and reinterpretations of the chair have been created over the years, demonstrating its flexibility and adaptability to different aesthetics and needs. Several chairs are related to Wassily in some way: one could mention Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chair from 1929, also with tubular steel elements (but with a more solid and finished structure), or the Mart Stam chair by the Dutch designer of the same name, designed in 1926 with a cantilever structure similar to that of another Breuer chair, the Cesca chair, and then again the Weissenhof chair also by Mies van der Rohe. The concept of using industrial materials creatively and embracing functionality without sacrificing aesthetics had a defining impact on many subsequent designers. Its presence in design collections around the world, as well as in numerous museums, testifies to its importance as a timeless masterpiece and an inspiration for future generations of designers.

The Wassily chair thus remains a striking example of innovation and bold design. Through its innovative use of materials and its timeless form, it broke traditional barriers of furniture design and opened new avenues for creative expression. And even today, the Wassily chair is an extraordinarily relevant and contemporary object.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.