The “Sagarriga Visconti Volpi” National Library in Bari preserves the important archive of the Apulian intellectual, writer and humanist Tommaso Fiore (Altamura, 1884 - Bari, 1973), which he himself wanted to donate to the Apulian institute shortly before his death. For almost fifty years, in fact, Fiore had been in contact with the Library: at least until 1924, when, appointed by the province, he became a member of the institute’s board of trustees. Fiore was later forced to leave the post because of his anti-fascist convictions, but he was able to resume relations with the Bari library in 1943, in the aftermath of the fall of Fascism, when he was appointed extraordinary commissioner for reconstruction and concurrently headed what was then the Bari Consortial Library from 1943 to 1950.

Tommaso Fiore, after studying at high school, enrolled at theUniversity of Pisa in 1903, where he attended Giovanni Pascoli ’s lectures and where he came into contact with the theories of the anarchist Pietro Gori , which had then become quite widespread in Lunigiana and northern Tuscany. It was these experiences, combined with his university readings, that drew Fiore closer to socialism, convincing him of the idea that it was necessary to take the side of the humble and the last: thus began his decades-long social commitment, which began with a few articles in the journal Rassegna pugliese (Fiore had in fact returned to Altamura in 1907). In the years leading up to World War I, he held to the positions of democratic interventionism that spread among some southern intellectuals, above all Gaetano Salvemini: the belief was that the war could subvert the old world order based on oppressive imperialism, sanctioning the self-assertion of peoples. Fiore himself left for the front in 1916, and on his return in 1919, he continued his commitment, siding with veterans who returned from the war and continued to be harassed by the old logics of power, which had not changed in the South. He thus became actively engaged, as he was also mayor of Altamura between 1920 and 1922.

After the rise of Fascism, he held clear anti-fascist positions from the start, believing that Mussolini’s ideology was contrary to the interests of the workers and, indeed, was a useful tool, if anything, for the reactionary bourgeoisie. He became close to the United Socialist Party, was in contact with Piero Gobetti, Carlo Rosselli and Pietro Nenni, and for this he was being watched by the Fascist authorities, who subjected him to constant scrutiny. In 1937 he obtained the chair of Latin and Greek at the Molfetta classical high school, and in the meantime had begun to collaborate with the Laterza publishing house, for which he translated Tommaso Moro’sUtopia (also writing the preface that introduced it). In the meantime he had approached liberal-socialist positions, becoming one of the main theorists of this line, a circumstance that brought him closer to figures such as Aldo Capitini, Guido Calogero, Guido Dorso, Leone Ginzburg and the Justice and Freedom movement. He then intensified his anti-fascist propaganda and therefore ended up sentenced to confinement. In 1943 he was also imprisoned for his ideas: he was released from jail on July 28, 1943, a few days after the fall of the regime, but his exit from prison was shattered by the news of the loss of his son Graziano, who was killed by police during the massacre in Via Niccolò dell’Arca, carried out by the Royal Army, Carabinieri and fascist militants who intervened to suppress a peaceful anti-fascist demonstration by students, in which Graziano Fiore had also participated.

From that moment on, Fiore took personal action to restore the freedoms that had been suppressed by the Fascists and thus became one of the leading intellectuals in southern Italy. He promoted the first congress of the Committees of National Liberation of Free Italy held in Bari in 1944, in the same year he was appointed superintendent of studies and engaged in the operation to defascistize schools and society, waged a battle for the autonomy of secular culture and, from 1946 to 1954, held the chair of Latin literature at the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Bari. His last years saw him constantly active in the struggles for democracy, freedom, peace, and dialogue among peoples: it is recalled in particular, before his death in Bari on June 4, 1973, his editorship of the journal Il risveglio del Mezzogiorno, dedicated to issues concerning the southern question.

Postcard

Postcard Postcard

PostcardTheTommaso Fiore Archive of the National Library of Bari is divided into two parts, theEpistolary and theArchive proper, and the documents kept in the fund date from 1942 onward. The archive contains documents that frame Tommaso Fiore’s collaboration with newspapers and journals but also his participation in conferences, plus it is possible to find essays, prints, pamphlets, notes, notebooks, personal papers, miscellaneous material drafted from 1942 to 1961, as well as teaching materials that Fiore used at the time of his teaching at the University of Bari.

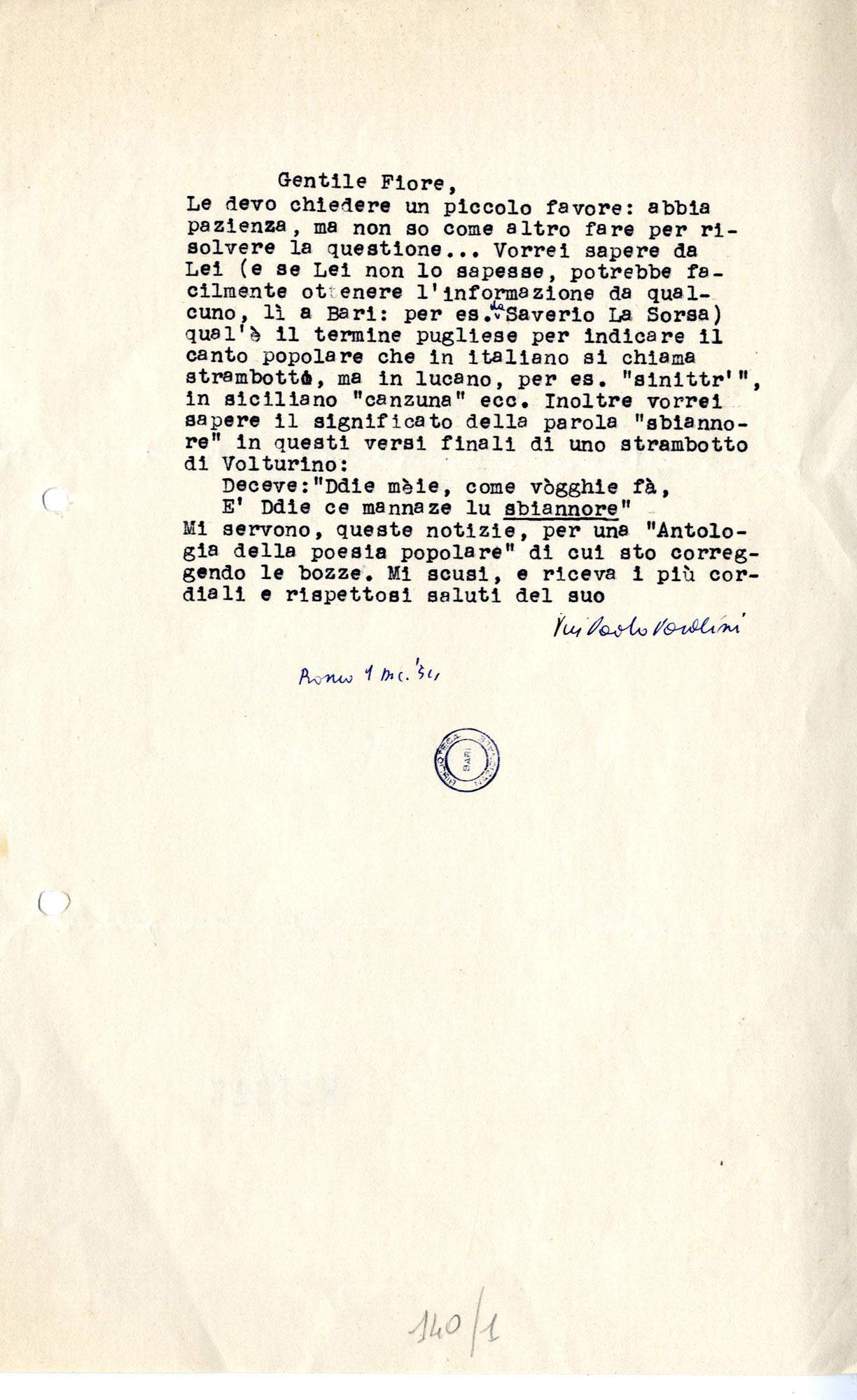

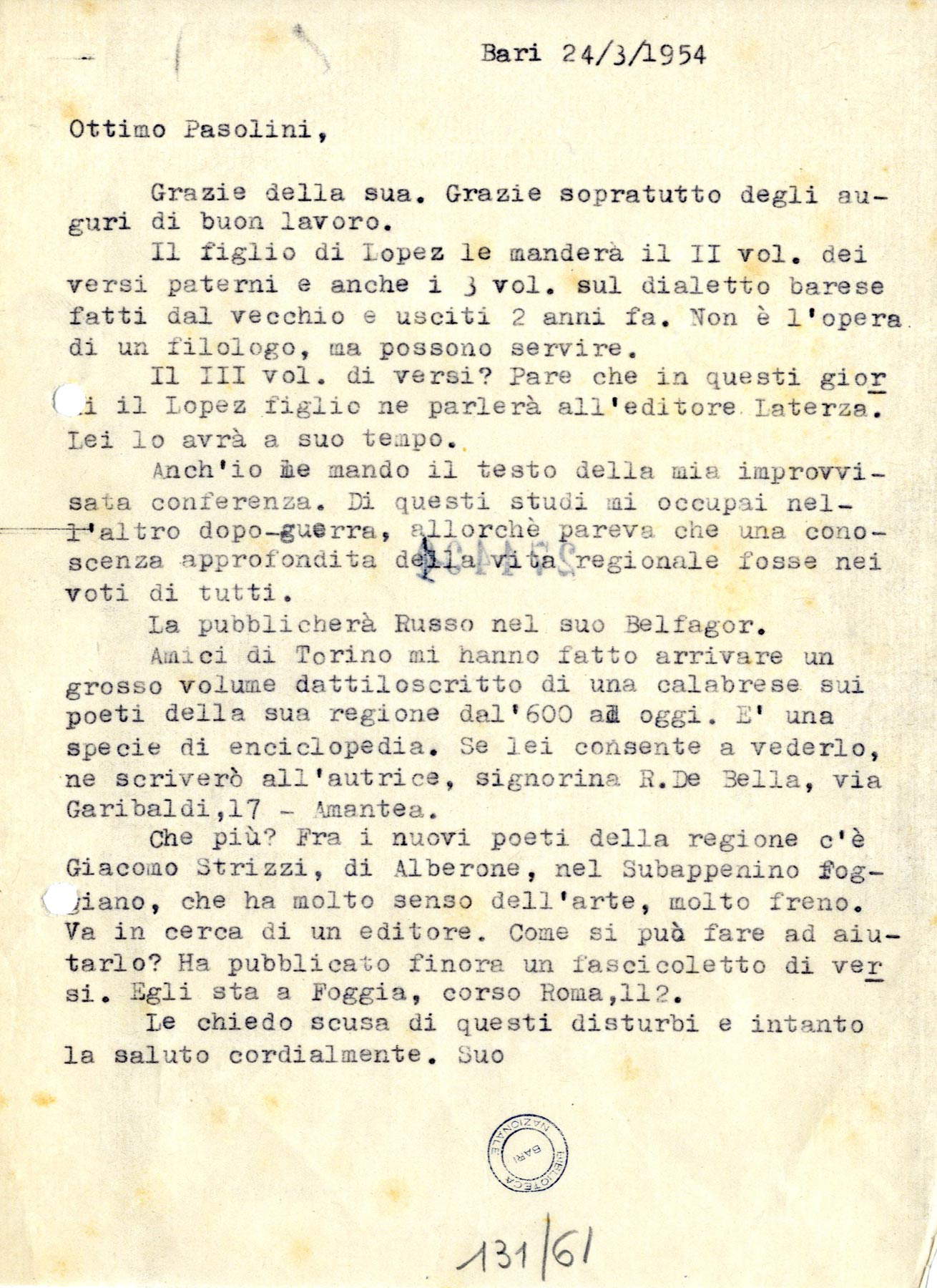

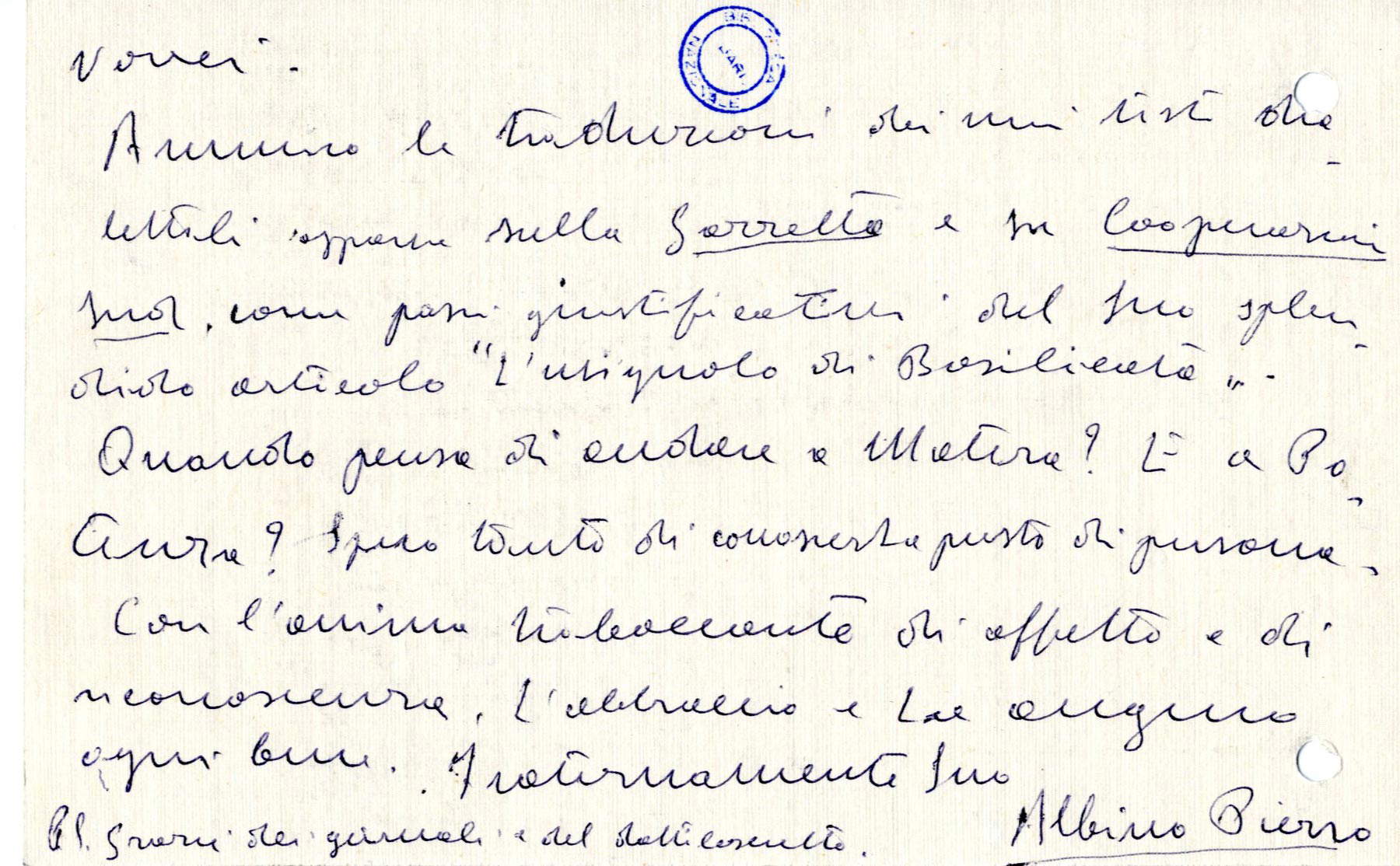

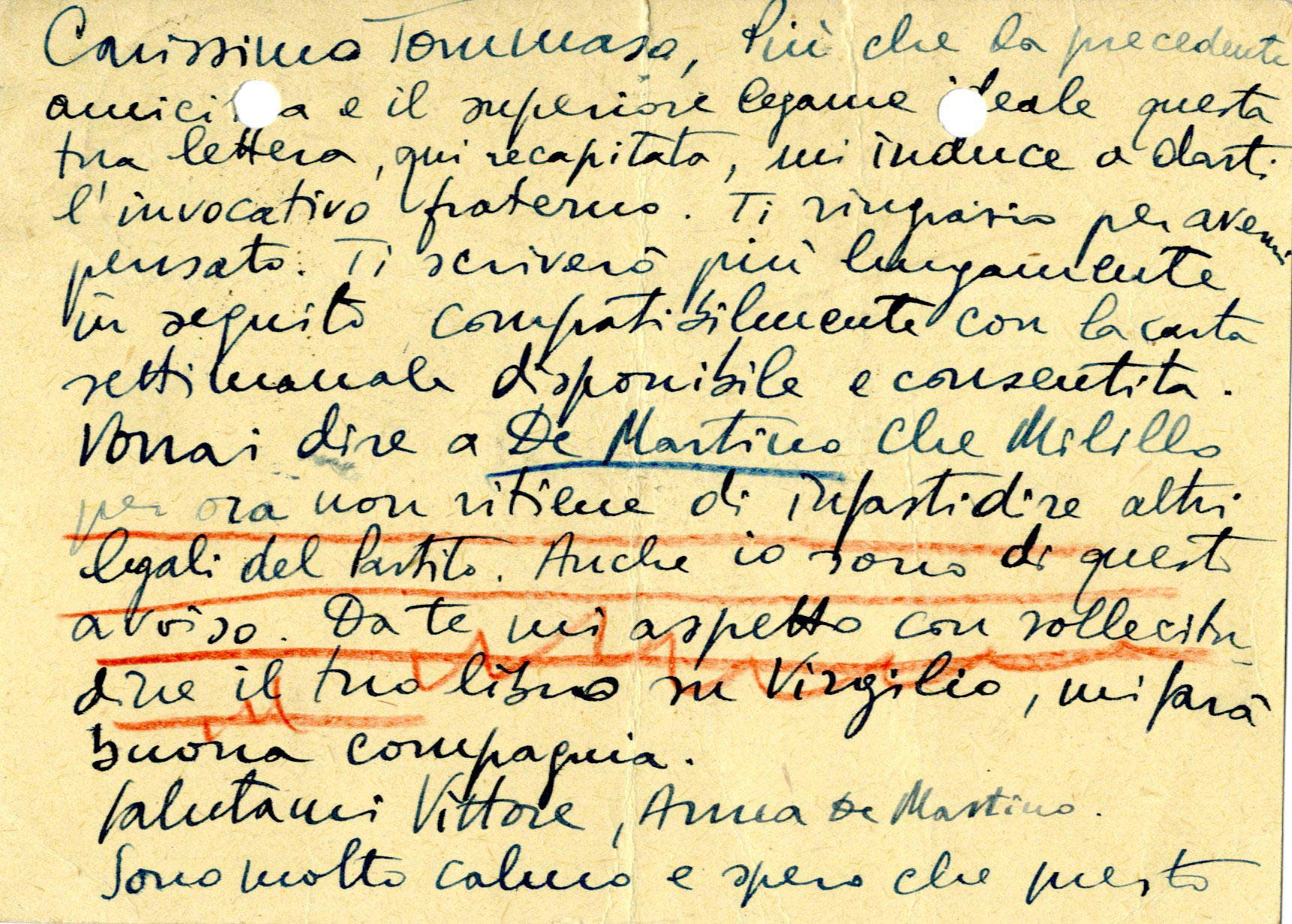

To reconstruct his personality and the network of contacts with whom he maintained relations, on the other hand, it is possible to refer to the epistolary, which includes more than 13,000 letters and gives an account of a daily correspondence with leading figures in the intellectual circles of Italy in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s (in fact, the correspondence covers a period from 1943 to 1966). There are complete correspondences with Sandro Pertini, Guido and Teresa Dorso, Carlo Muscetta, Gabriele Pepe, Tommaso Castiglione, and Maria Brandon Albini, plus also exchanges of letters with Benedetto Croce, Carlo Sforza, Gaetano Salvemini, Don Lorenzo Milani, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Aldo Capitini, the letters sent to newspapers such as l’Avanti, Il Paese, Il Contemporaneo, Mondo operaio, with publishers such as Laterza and Einaudi, and with various cultural associations. With Pasolini, for example, Fiore exchanged news and opinions of a literary nature. In a letter dated March 24, 1954, the Apulian intellectual sent the Friulian writer some works in Bari dialect that he considered interesting for the research Pasolini was doing on popular poetry (and Pasolini would not fail to ask Fiore about certain dialect terms whose meaning he did not know), and in return asked him what could be done to help a young poet from Foggia, Giacomo Strizzi, find a publisher for one of his poetic works.

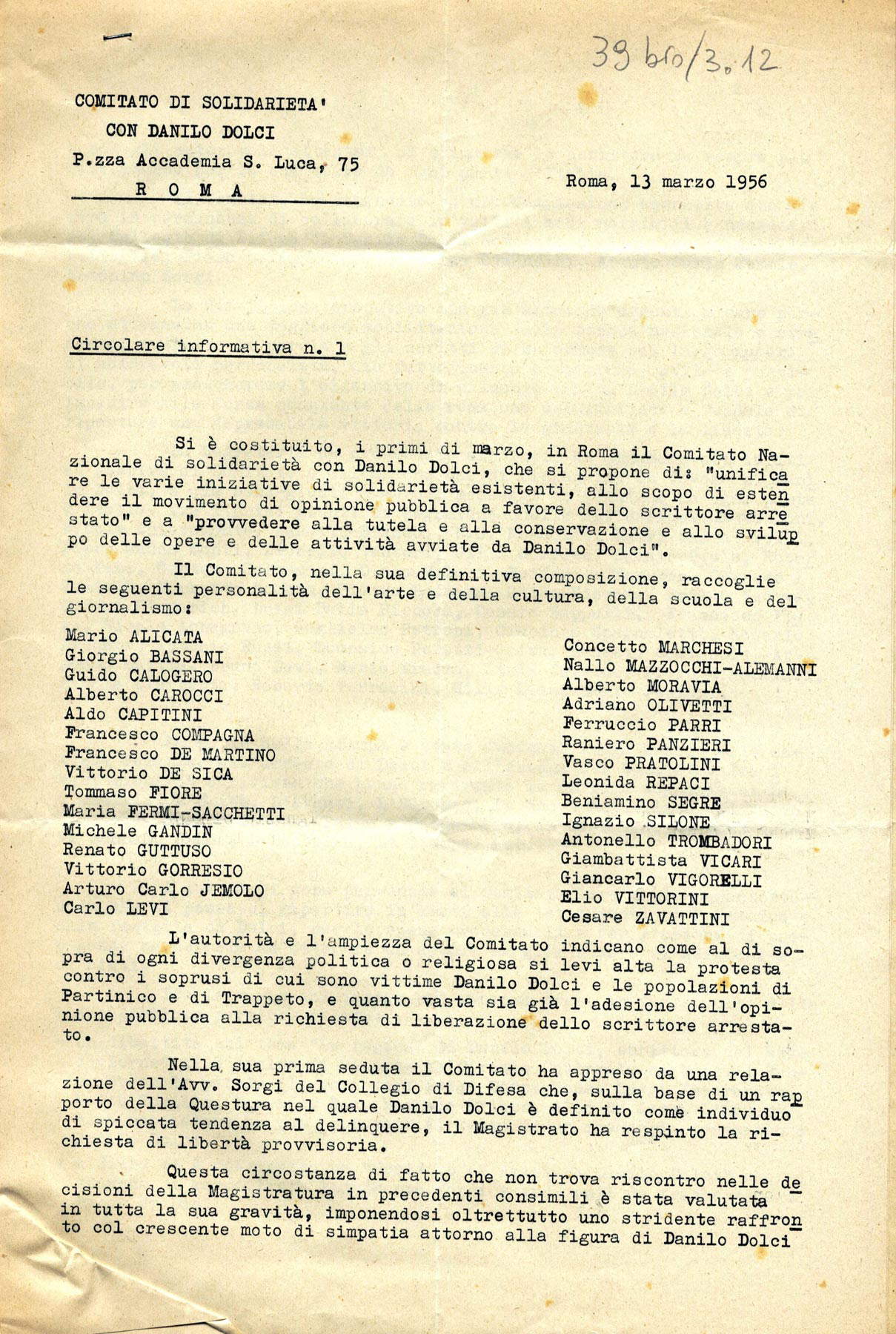

Among the most interesting documents in the collection, however, are those from which the figure of Tommaso Fiore emerges as a great man of peace. Fiore turns out to be the founder, in 1956, of the National Committee of Solidarity with Danilo Dolci, along with a large number of intellectuals that included Giorgio Bassani, Guido Calogero, Aldo Capitini, Vittorio De Sica, Renato Guttuso, Carlo Levi, Alberto Moravia, Ferruccio Parri, Vasco Pratolini, Leonida Repaci, Beniamino Segre, Ignazio Silone, Antonello Trombadori, Elio Vittorini, Cesare Zavattini and others. The committee’s goal was to support poet and activist Danilo Dolci (Sesana, 1924 - Trappeto, 1997), who, beginning in 1952, had become involved in a number of nonviolent protests in Sicily, where he had moved that year. On January 30, 1956, Dolci had been among the animators of the “upside-down strike,” a particular form of protest during which some workers had decided to redevelop an abandoned road.Dolci and other activists were arrested on charges of resisting and insulting a public official, inciting disobedience to laws, and land invasion. A trial ensued (Dolci’s defenders included Piero Calamandrei) that had a wide resonance: Dolci was sentenced to 50 days in prison, but on his side were not only members of the committee of which Fiore was a member, but also a great many other intellectuals of the time, from Bertrand Russell to Jean-Paul Sartre, from Norberto Bobbio to Bruno Zevi.

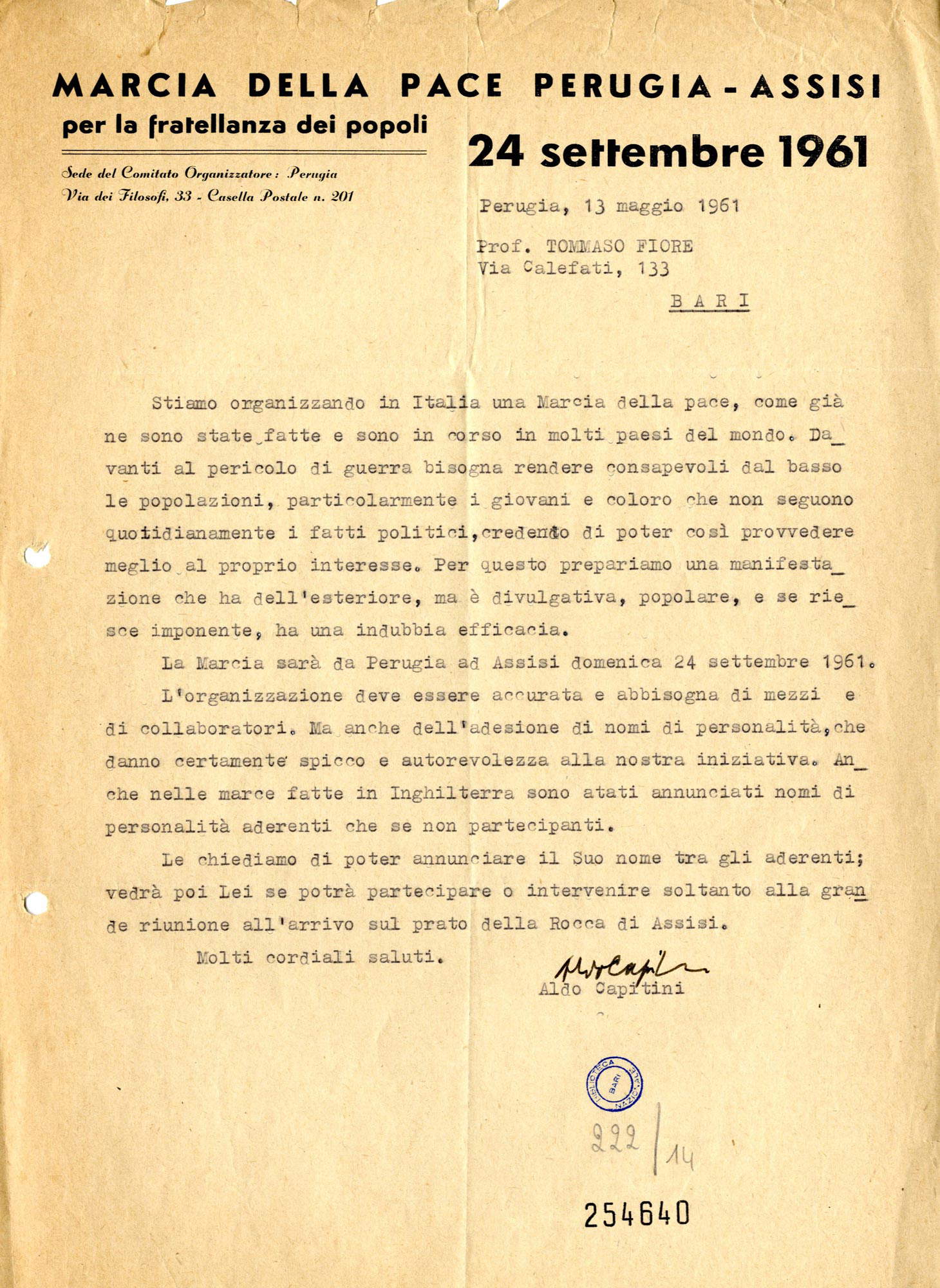

Even more active, however, was Fiore’s role in the Peace March, the most famous event of the Italian peace movement: a twenty-four-kilometer route, from Perugia to Assisi, to speak out openly against wars and generally against all forms of violence. The Peace March has been held since 1961, the year of its first edition, organized for September 24 of that year by Aldo Capitini as a nonviolent procession inspired by the demonstration that British pacifists, led by Bertrand Russell, had organized in 1958 in Aldermaston, a town of not even a thousand inhabitants that was the headquarters of the research facility of the U.K. Ministry of Defense responsible for the design and development of the country’s nuclear weapons. “We are organizing a Peace March in Italy,” Capitini wrote to Fiore on May 13, 1961, “as have already been done and are being done in many countries of the world. Faced with the danger of war we need to make people aware from below, particularly young people and those who do not follow political events on a daily basis, believing that they can thus better provide for their own interests. That is why we are preparing an event that has some exterior, but is popularizing, popular, and if it succeeds impressively, has undoubted effectiveness.” The march, Capitini wrote, needed “names of personalities who certainly give prominence and authority to our initiative”: he thus asked Fiore to give his endorsement.

Tommaso Fiore not only participated in the march between Perugia and Assisi, but worked to organize one in Puglia. In 1962, the year after the Cuban missile crisis, in an area, that of the Murgia, which at the time was among the most heavily armed in Italy (the United States, since 1959, had installed eight Jupiter nuclear missile launching fields in the area: Gioia del Colle, Mottola, Laterza, Altamura-Casal Sabini, Gravina di Puglia, Quasano, Spinazzola and Acquaviva delle Fonti, to which were added two in Basilicata, in Irsina and Matera), Fiore led afurther peace march between Altamura and Gravina di Puglia, two of the towns where the Americans had planted their bases, which would later be completely dismantled that very year as a result of the Cuban crisis.

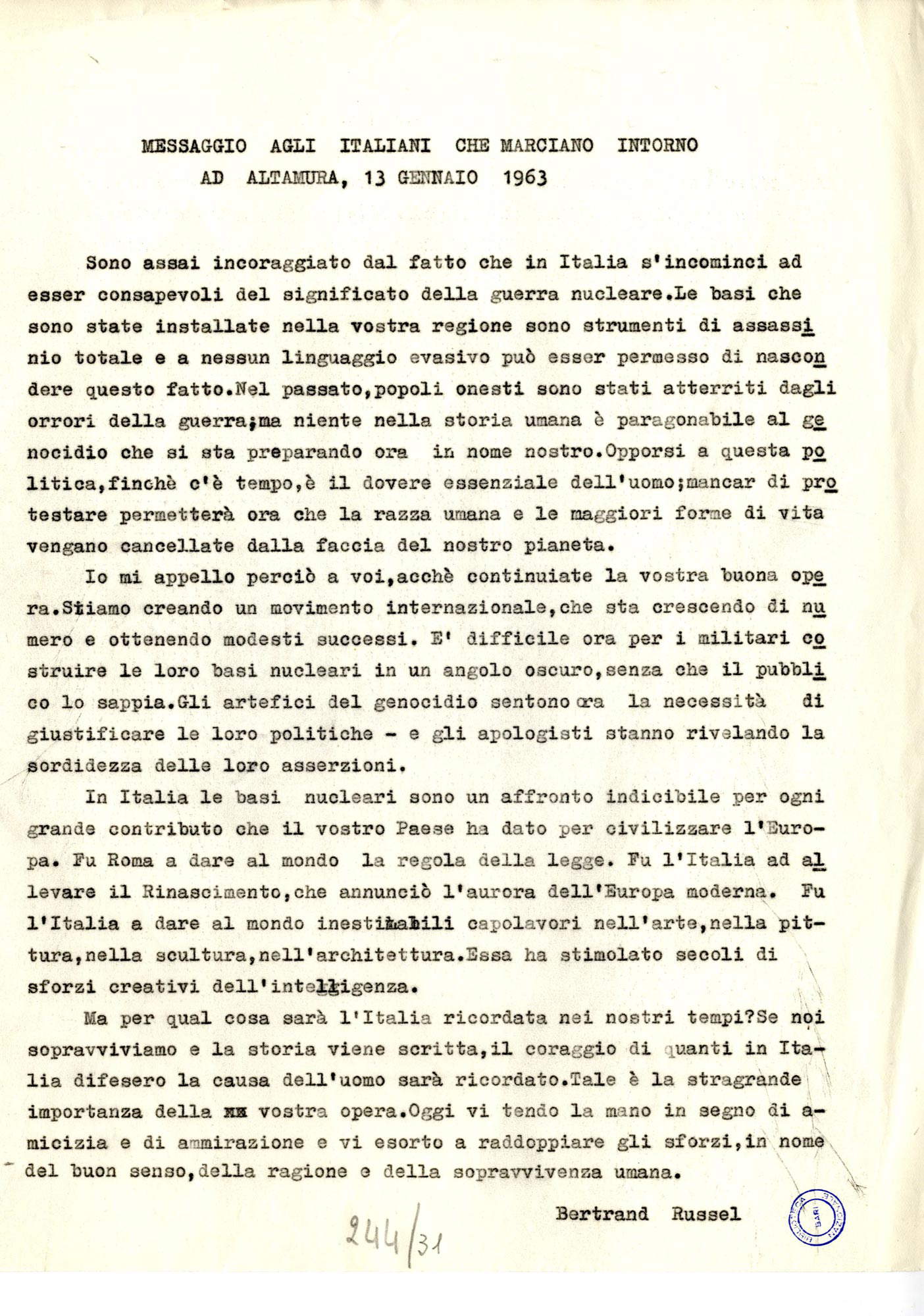

The initiative received the praise of Bertrand Russell, who on January 13, 1963, had Fiore deliver a Message to the Italians marching around Altamura: “I am greatly encouraged,” Russell wrote, “by the fact that in Italy people are beginning to be aware of the significance of nuclear war. The bases that have been installed in your region are instruments of total murder, and no evasive language can be allowed to conceal this fact. In the past, honest peoples have been appalled by the horrors of war; but nothing in human history compares to the genocide now being prepared in our name. To oppose this policy, while there is time, is the essential duty of man; to fail to protest will now allow the human race and major life forms to be wiped from the face of our planet. I therefore appeal to you to continue your good work [...]. In Italy nuclear bases are an unspeakable affront to every great contribution your country has made to civilizing Europe. It was Rome that gave the world the rule of law. It was Italy that bred the Renaissance, which heralded the dawn of modern Europe. It was Italy that gave the world priceless masterpieces in art, painting, sculpture, architecture. It stimulated centuries of creative efforts of the intelligence. But for what will Italy be remembered in our time? If we survive and history is written, the courage of those in Italy who defended the cause of man will be remembered.”

Organizers of the event met to decide the details right at Tommaso Fiore’s home. Not all political parties adhered to the peace march organized in the writer’s hometown: there was a section of politics that branded the march as pro-communist, since some participants came from that area, and since a few months earlier China had attacked India, resulting in a war that lasted only a month but had significant repercussions. The march, therefore, lacked the adhesions of the Psdi, the Christian Democrats, and the Uil. Yet, Fiore and his collaborators wanted to make it clear right away that the demonstration had no colors nor was it heterodirected, but was inspired precisely by Russell’s activities, which were anything but pro-communist. The reasons for the march were explained in the manifesto published in the Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno of January 5, 1963: “The people of Puglia and Lucania are called once again to express their intentions in favor of an Italian policy of peace and friendship with all peoples, by participating in the Altamura Peace March. We, we Italians, have no problems of strength to solve with any country, neither near. Nor far away. The atomic armament to be added to our armed forces is certainly not an act of détente and contribution to peace. The atomic ramps in the hills of Apulia are a sinister death call and the wisest and most urgent thing is to remove them, through the commitment of our government that tends to the atomic disengagement of all of Europe and worldwide disarmament. We Apulians and Lucanians do not want war ramps on our lands; we demand peace industries.”

The Altamura-Gravina March, although not as famous as the one that now unites Perugia and Assisi almost every year, has had other repetitions. The second was organized in 1987, against the installation of military polygons in the Murge. There were then two reruns in 2003, against the war in Iraq, and in 2005, to demand more attention for the environment of the Alta Murgia Park. And then the fifth, on March 19, 2022, for peace and disarmament, in the context of the war between Russia and Ukraine, with a call to activate all diplomatic measures to resolve it. The legacy of Thomas Fiore thus continues to be alive.

The origins of the library date back to 1863, when the Bari senator Gerolamo Sagarriga Visconti Volpi offered his personal library, consisting of about two thousand volumes, to the Municipality of Bari: his desire was to create a public library, at a time when Bari did not have one. The donation was formalized on April 5, 1865, and in 1877 the library was opened to the public: in the meantime, its library holdings had grown to 14,000 volumes, thanks to further donations from private individuals that had been added to that of Sagarriga Visconti Volpi and the acquisition of the libraries of convents suppressed in the province after the Unification of Italy. The City Palace, near the Basilica of St. Nicholas, had been chosen as its headquarters. In 1884 the City Council and the Province formed a consortium to manage the institute (which was thus named “Biblioteca Consorziale Sagarriga Visconti Volpi”), and in 1895 the Library was moved to the ground floor of the Palazzo Ateneo, which had just been built by the Province, designed by architect Giacomo Castelli. Instead, it dates back to 1958 when it was transformed into a state library with the title of national, with the consequent expansion of its responsibilities.

In the 1970s the Sagarriga Visconti Volpi Library underwent a radical modernization of its facilities, services and technical-scientific organization, a circumstance that transformed the library, partly through the purchase of bibliographies and reference works, into the most important regional bibliographic center, both in terms of the importance of the patrimony preserved and the rigor of library procedures, the validity of acquisitions, and the preparation of the scientific staff.

The Library holds about 500,000 printed books to which are added 454 volume manuscripts and 16,642 loose manuscripts, and 682 parchments. Among the most important manuscripts are the autograph of Giacinto Gimma’s Encyclopaedia, the Libro Magno dei privilegi della città di Bari, a copy of Il Regno di Napoli distinto in dodeci provincie, an atlas attributed to Mario Cartaro and Antonio Stigliola, the Conclusioni decurionali dell’University of Bari pertaining to the years 1513, 1516, 1548, 1565, 1576, 1577, 1580, 1581, 1583, 1584, and then again the De Ninno Fund, which collects the private archives of historian Giuseppe De Ninno. As for printed books, of considerable importance are the Domenico Zampetta donation (about 25,000 volumes containing works of mainly literary and French-language interest, relevant for rarity and bibliographical particularity), the Raffaele Cotugno donation (about 20.000 printed works of historical-political interest concerning southern Italy in particular; it also includes an interesting collection of periodicals and newspapers and an archive concerning the Risorgimento and southern political life from the late 19th century to the advent of Fascism), the Michele Squicciarini donation (numerous valuable antique editions), and the Andrea Angiulli donation (homogeneous fund of about 2,000 volumes of works on philosophy). The Library also possesses 55 incunabula, mostly of convent origin, and consequently of theological and philosophical content. Also present are about 1,800 cinquecentine mostly from libraries of suppressed convents acquired to the state patrimony, 634 deeds concerning southern Italy issued in the period between 1718 and 1867, 750 maps from the 16th to 20th centuries, and the Rare and Precious collection that includes some ancient atlases and finely illustrated works from the 17th and 18th centuries as well as others enriched with valuable bindings and manuscript notes of famous people.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.