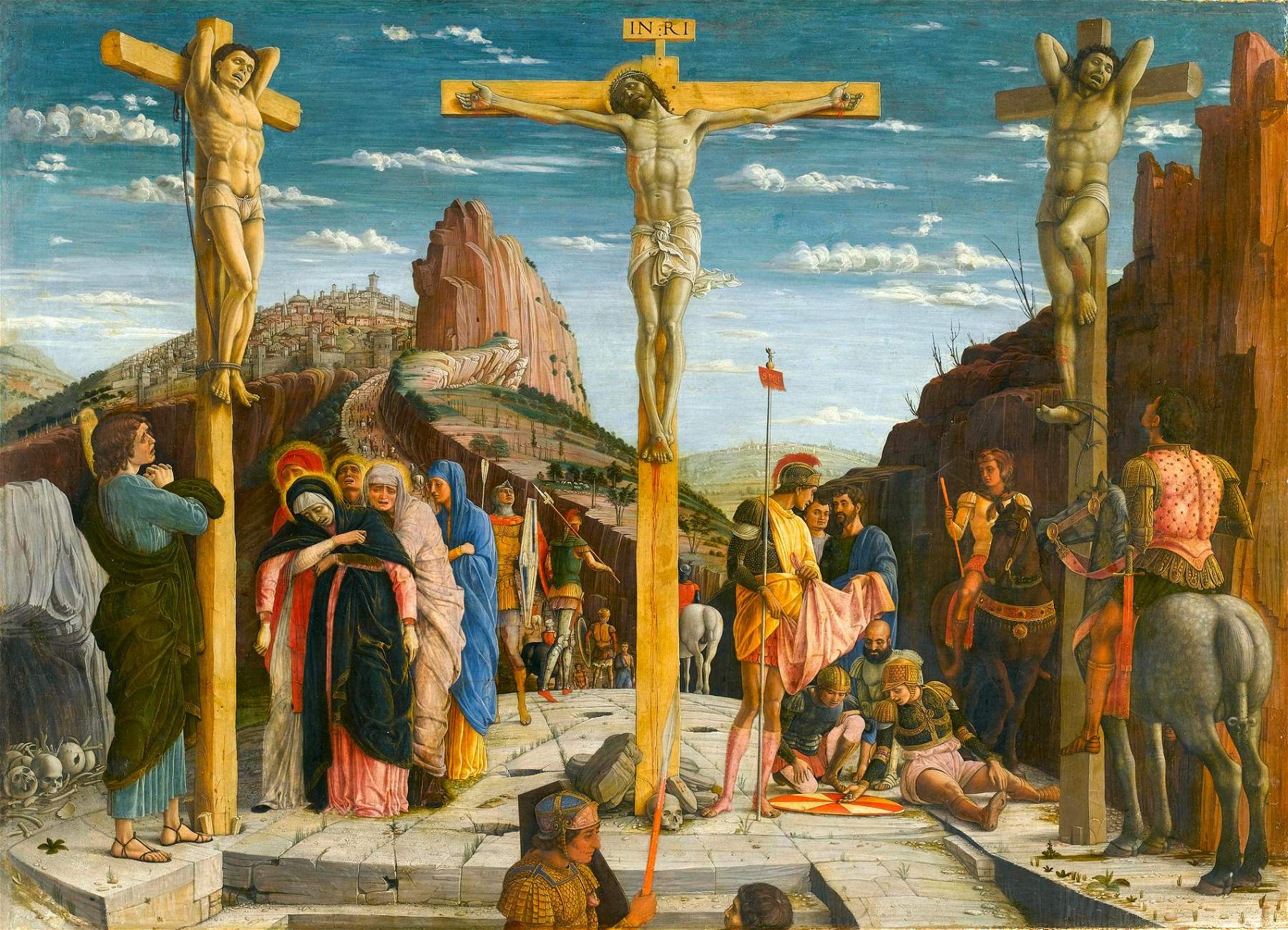

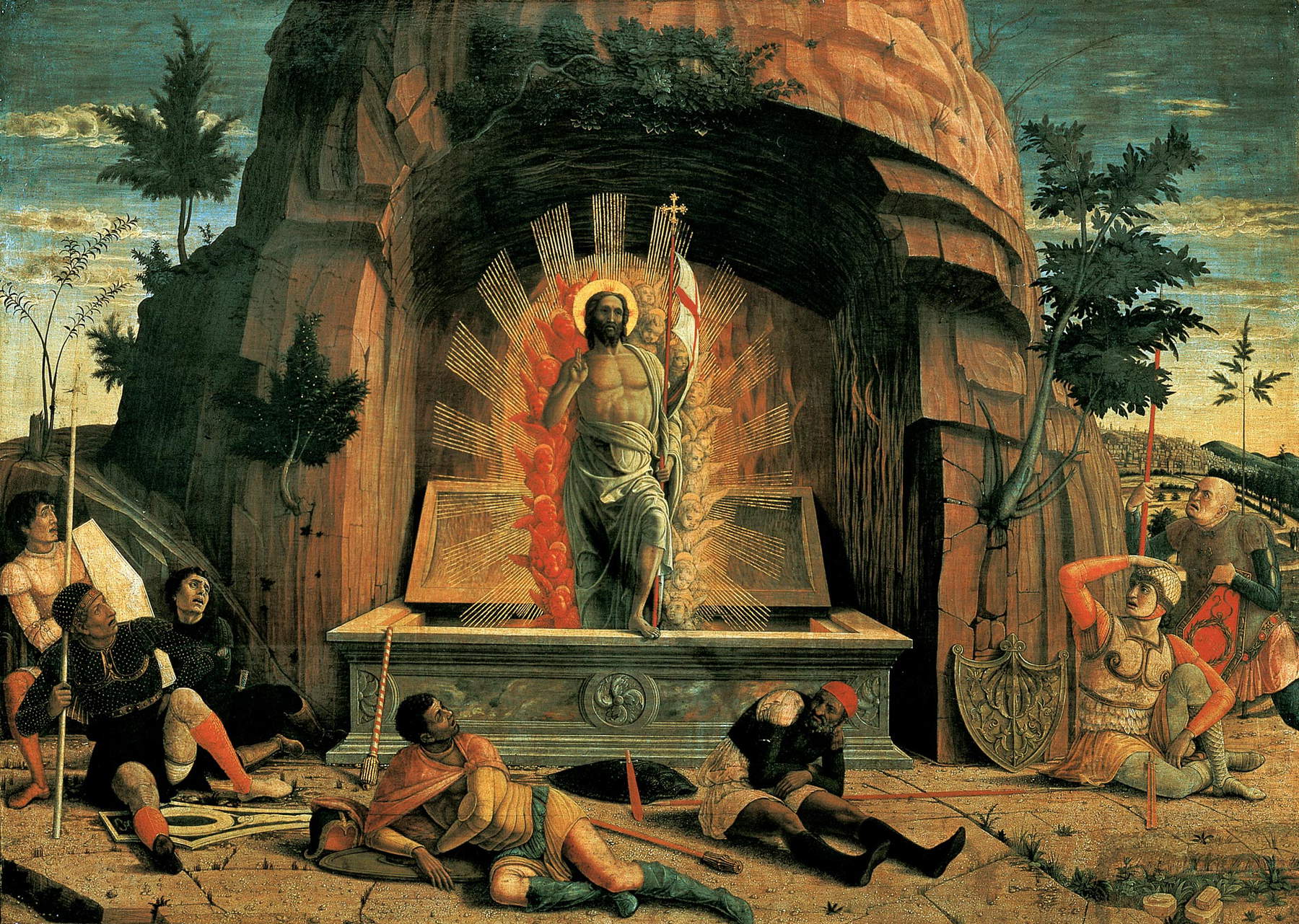

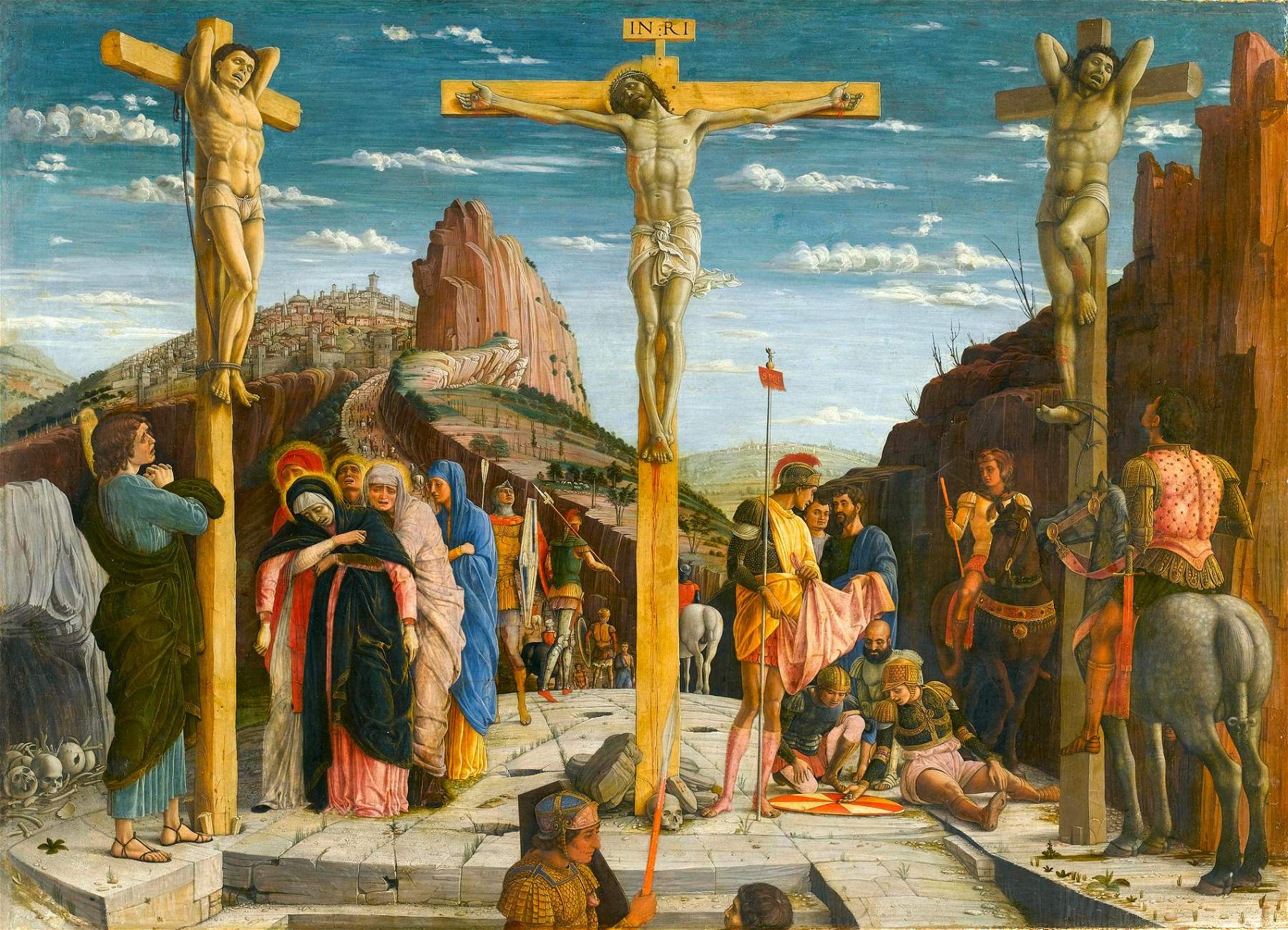

Will France return to Italy three valuable Andrea Mantegna panels taken by Napoleon shortly after the Treaty of Campoformio was signed? Difficult, but it can be discussed. Yesterday, Le Journal des Arts, one of the leading French publications dedicated to art, published an article signed by Emmanuel Fessy in which in fact the debate is kicked off: it would involve returning to Italy the three compartments of the predella of Andrea Mantegna’s San Zeno Altarpiece, an early masterpiece of the great artist from which the Veronese Renaissance took off, preserved in the church of San Zeno in Verona. During the Napoleonic spoliations the work took the road to Paris: it returned to Verona, but the three compartments of the predella (with the Prayer in the Garden, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection) remained in France, and today two of them are in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tours, while the third, the Crucifixion, is in the Louvre. The predella seen today in Verona is a reproduction.

“Nowadays,” writes Fessy, “great efforts are made to find the missing panels in order to restore a work to its state of integrity, fulfilling the artist’s wishes. The hunt is enormous and laborious because dispersal has spread over the years to Europe and the Americas. It is rarely successful. Yet there is one Italian Renaissance masterpiece that has suffered such mutilation and could be reassembled: the altarpiece designed by the young Andrea Mantegna for the Benedictine abbey of San Zeno in Verona.” Recomposing the dismembered polyptych, Fessy argues, would be easy, unlike other cases, but it would also be a politically ambitious goal.

In 2009, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tours had organized an exhibition that had been described as “historic” and had brought together the three compartments of the predella of the San Zeno Altarpiece: in fact, it was the first time since 1930 that the Louvre had lent the Crucifixion. However, writes Fessy, “the real event would be the return of the predella to Verona.” Today museums are going through a period of profound rethinking and as a result, the journalist writes further, “they can no longer ignore debates about provenances and their consequences. The San Zeno altarpiece is a unique case because it can be reconstructed in its integrity and in its place of origin, the abbey for which Mantegna had conceived it, where he had solved the challenge of the relationship between the work and the space.” The “retention in France of Mantegna’s predella, moreover fragmented, must therefore be discussed today,” Fessy concludes. “The Louvre and Tours would lose three major medium-format works but would enter a new phase in their history.”

France is currently conducting important work on museum collections in order to return works taken during colonial occupation to their countries of origin. One of the latest returns is that of 26 objects from the treasures of the Danhomé kingdom taken by the French between 1890 and 1894 during the Benin colonization war. On Italy so far there has been no discussion, partly because for our country the issue is quite different: at the time of the spoliations, Napoleon succeeded, for the first time in history, in having the requisition of art objects as war compensation included in the treaties signed with the defeated powers. After the Restoration, many of the occupied states, after lengthy legal battles, succeeded in having the clauses imposed by Napoleon considered null and void, thus allowing many works to be returned to Italy (a masterpiece in this regard was accomplished by Antonio Canova, who as papal commissioner for the recovery of works succeeded in having many of the confiscated works returned to Rome). In short, the road is long and winding, however, it is interesting to note that we are also beginning to discuss restitution from France to Italy.

|

| Will France return to us three Mantegna panels stolen by Napoleon? Debate opens |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.