A high and singular de Chirico Exhibition in Modena. A happy event that brings new light to a powerful beacon of art. We take this precious opportunity certainly not to bore the reader and dissert again on the innumerable volumes already expressed around the phenomenon of European Surrealism where our painter was first priest. We only wish to remark the event in all its value and would like to approach it almost with a play on thought that would like to that corner of facetious humor that the great Giorgio always carried with him.

Was Giorgio de Chirico ever in Modena? That is, has he ever sojourned in this city, twin of Ferrara, where the “is not” expands to a dance of adjectives that weave restless mysteries, rich in images and sensibility, that support research and poetry? Modena is clamped by two rival rivers, it is reluctant and strong; it offers the pervading spirit dilemmas of deep emotion with its Duomo cocooned in eternal stone and its incredible tower, wedged in the watery earth, calling to the other distant towers of cities and Abbeys: it is a city of steadfastness in this now silent Cispadan land that once saw, as in a dream, “women, knights, arms and loves”! All subjects in duet with him.

But today De Chirico came with an astonishing exhibition, since this diver of suspended atmospheres here certainly ideally rested in that symphonic turn that takes the spirit in the preternatural antinomies of enigmas, and which the dialectical painter always brought to tenzone. What then was the remote echo of the dialogue between the mute inquiring George and the motionless, sublime Wiligelmo?

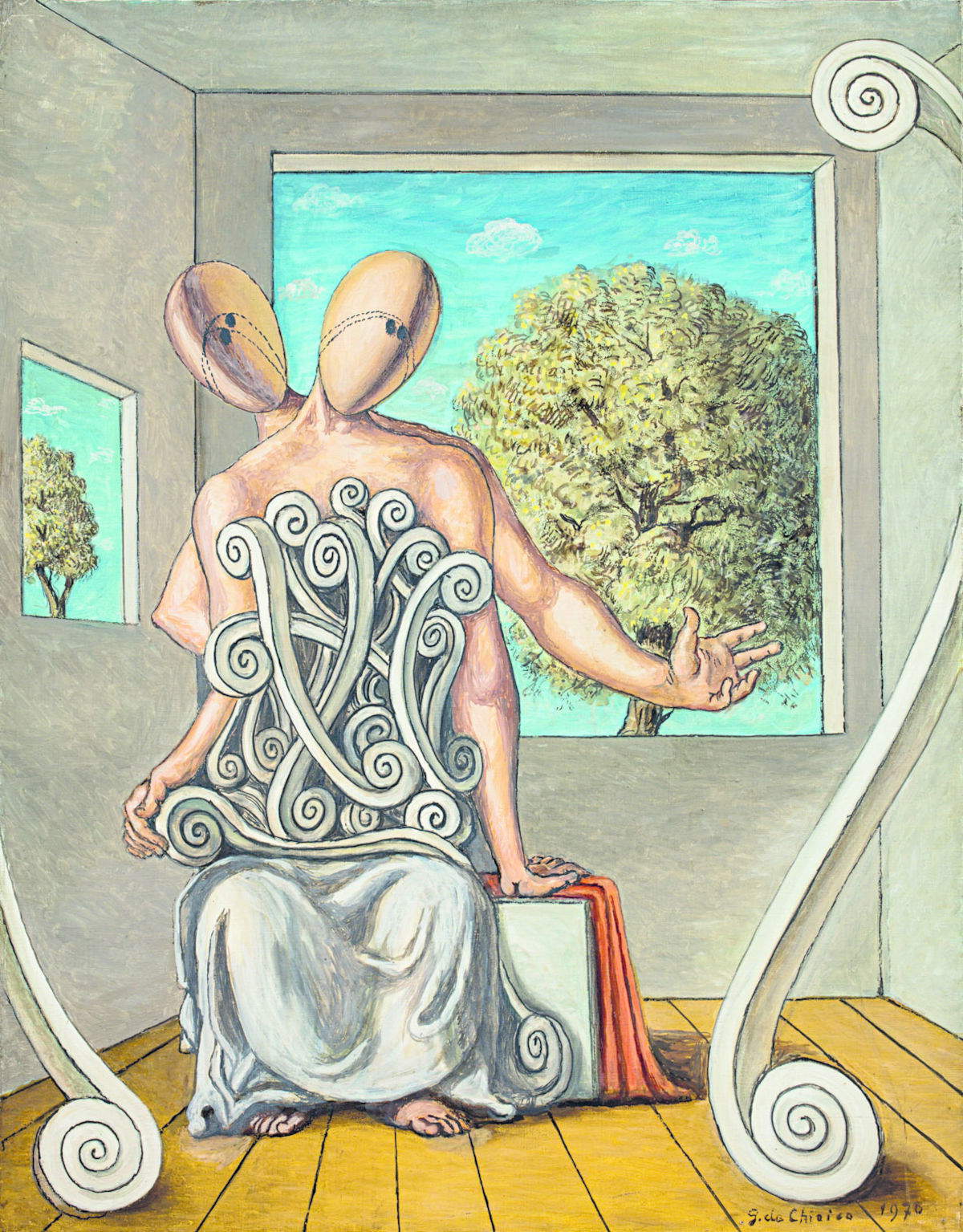

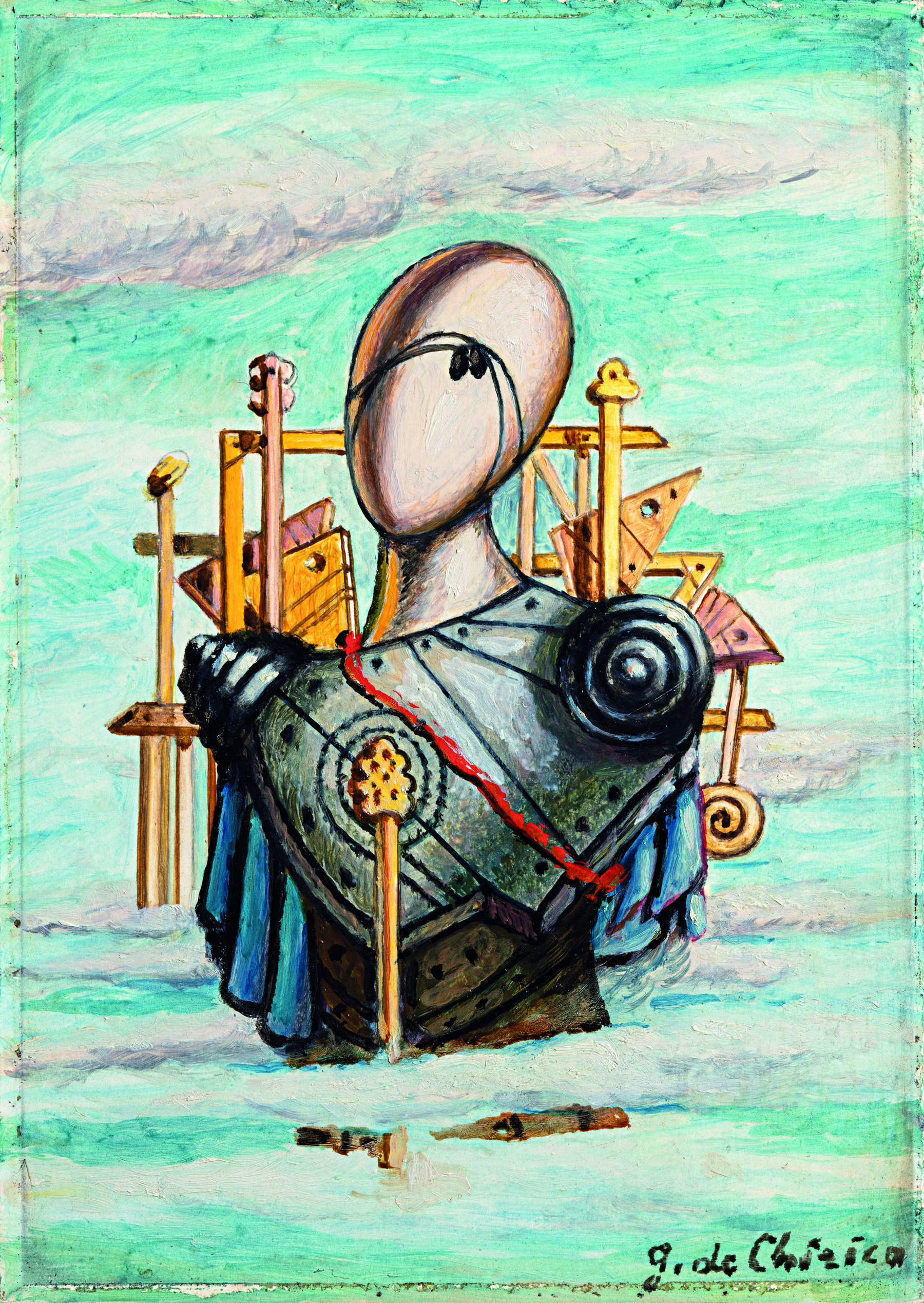

And we must ask another question, which invests a personal history, but also the history of European art of our time: was Giorgio de Chirico in his long pictorial adventure also far from his metaphysical stigma? Did he have opposite, different periods? We believe not, we believe in essence that his salient classical sap -- of disconcerting measure, and precisely for this reason modern -- remained alive throughout his career and invariably resurfaced in a still numinous but limpid sense in the last period of his fecundity. So that it is supremely valuable.

The Modena exhibition Giorgio de Chirico. L’Ultima Metafisica, Palazzo dei Musei, until next April 12, is a national event, but one of universal scope. It is Italian art, in words of new discovery, that we are facing. That little boy born in Greece bore as his first name “Joseph,” which evokes two characters with biblical echoes: one of the one who was sold into Egypt and triumphed in a foreign land, and the other who was the tenacious companion of the Holy Family among a thousand labors in the shadows. From the two he seems to have taken the tenacity, the straightness of path of a lifetime. And with the new name of Giorgio he prepared himself for the great tournament of art, where he rejected the sharp if beautiful and lonely pictorial depiction in order to dissect irradiating truths, always restless: “obscura de re lucida pango” might have been his motto in the ancient antinomy between the insidious figurative proposal and the Pascolian “unseen,” so capable of questioning the soul.

The exhibition in Modena - it can be said - was lacking in the intense, conclusive prospecting of De Chirico’s artistic life, in his necessary language, in his ever-pressing game of recalling the extreme step of “what” there is beyond the senses. An exhibition that is truly fruitful to our studies of the greatest pictorial hermeneut of a West from the tragic and pulsating twentieth century, but one that transcends all boundaries of time.

And it is to the enlightening, broad vision of Elena Pontiggia that now the great master’s Surrealism is placed in the indispensable light of his career, but equally it remains highly personal and even more precious in harmonious compositions and a particularly careful execution that makes each painting of this last phase like a peremptory preposition of the ancient self-analysis, which becomes the most challenging and rich adventure for every observer. Indeed, it is the observer who is involved to the point of desire for possession, that possession which is the true attitude of identification with an art that never neglects the call, the obligation of decipherment, and becomes the secret fulfillment of every intelligence.

De Chirico’s dialogical task thus becomes ever higher, and here Ara H. Merjian on “Anachronic Metaphysics: De Chirico circa 1968” becomes a solemn invitation for inquiring spirits, while the counter-song-so close to the painter’s deliberately listless character of humorous absence-is beautifully laid out by Francesco Poli in his essay “Metaphysical Irony,” more than useful at last for understanding the inner habitus of a callid histrionic man of sharp choices. Who can approach the supreme Giorgio? Restless spirits we would say, but parmenidean and all leaning toward being! Such ever-present spirits! The exhibition is indeed a stage for the reception of cultured people.

Writing about it, one cannot forget the intellectual and social “cast” that this event offers us. Elena Pontiggia in the first place, the Giorgio and Isa de Chirico Foundation, the Mayor of Modena Massimo Mezzetti, the Councillor for Culture Bartolamasi, the Directorate of the Museums of Modena, the famous art publisher “Silvana,” the ESSECI-Sergio Campagnolo Studio with its stalwart Simone Raddi. And each of the visitors will not forget the Modenese sojourn, which veraciously will be prodigal of truly seductive, rather than memorable, dulcitudes.

The author of this article: Giuseppe Adani

Membro dell’Accademia Clementina, monografista del Correggio.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.