The European visitor to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art who enters the unfamiliar and seductive space that is the American Wing, under its stained-glass windows that seem to seal off the works on display as if inside a crystal temple, cannot fail to pause in the rooms devoted to John Singer Sargent, culminating in the Portrait of Madame X, perhaps the most famous of the hundreds of portraits fired by the American painter. The canvas marks the culmination of Sargent’s Paris experience and at once the announcement of a farewell. Indeed, the scandal produced by his exhibition at the 1884 Salon was among the reasons that prompted the artist to leave the city that had consecrated his success two years later and move to London.

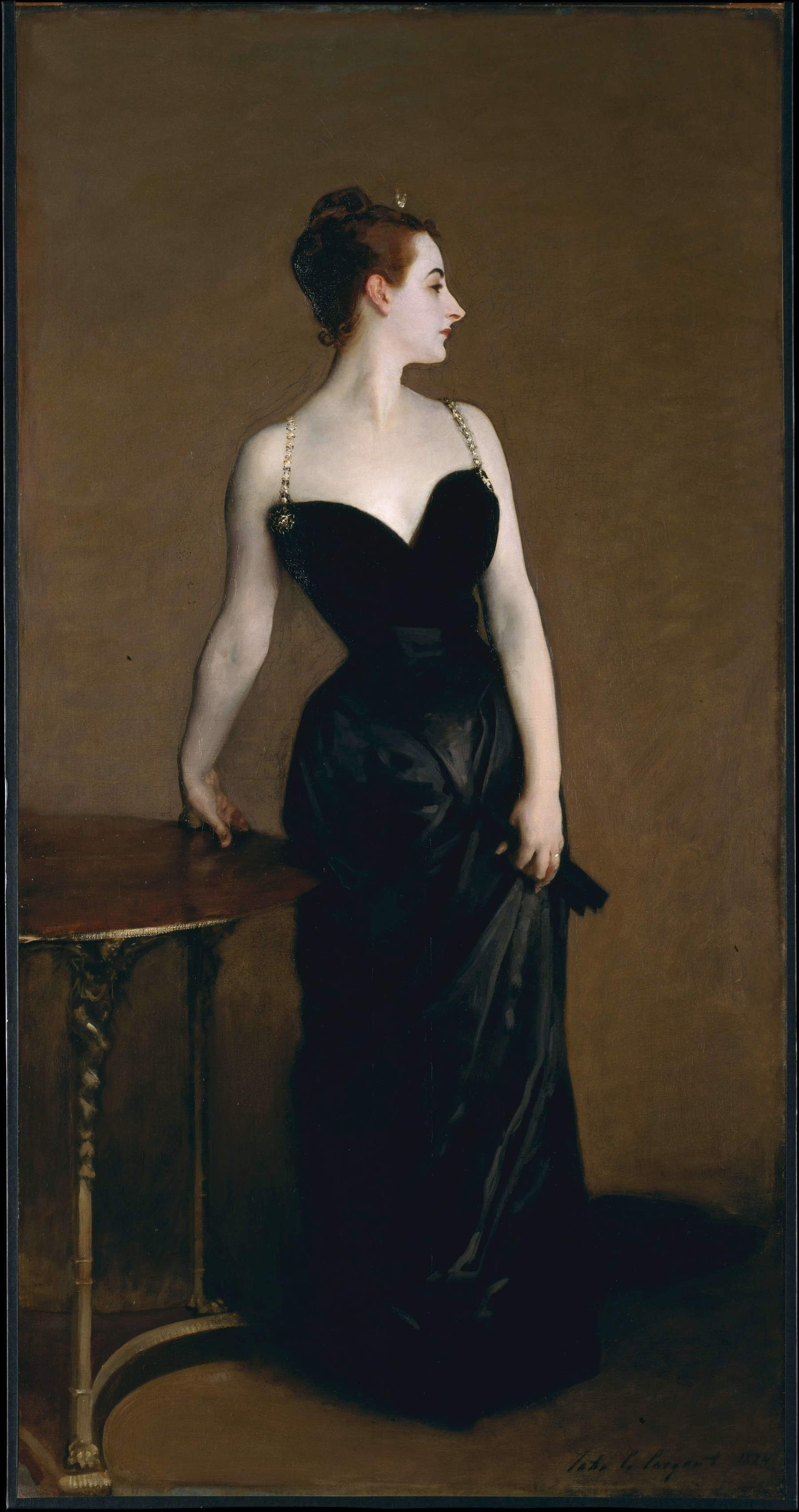

Unlike most of Sargent’s portraits, this one did not stem from a commission, but from the painter’s invitation, which convinced 25-year-old Virginie Amélie Avegno, born in New Orleans to a family of French émigrés and then married to businessman Pierre Gautreau, to pose for him. That somewhat angular face attracted him, so much so that he put it on full display in the final choice, made after a long series of studies, of the profile pose, which gives the face something like a bird’s beak that may recall the race of Guermantes described by Proust. The almost contemptuous gaze tinged with a hint of arrogance, the cast makeup, which in the eyes of a fellow painter gave the epidermis something “cadavérique et clownesque,” were not enough to arouse the indignation of the Salon audience. It was the boldness of the right shoulder pad nonchalantly abandoned on the humerus, which left the décolleté in a more pronounced and provocative nudity, that made the difference. The painting was withdrawn; Sargent, faced with the Gautreau’s refusal to take it home, kept it in his studio, reshaped the jeweled epaulette according to the conveniences of modesty, and, a year after the model’s death, sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Even the effigy’s name was subject to damnatio memoriae, and the painting has been known ictically as Madame X ever since.

Speaking of the famous canvas, we find ourselves at the heart of the exhibition Sargent. Éblouir Paris (curated by Caroline Corbeau-Parsons and Paul Perrin, in collaboration with Stephanie Herdrich), which, which originated at the Metropolitan, is staying at the Musée d’Orsay until Jan. 11, 2026. Despite the importance that the Parisian beginnings had on the artist’s career and the presence of works in French museums, this is the first monographic exhibition dedicated to him in France. It took the occasion of the centenary of his death to convince the French to take this step, not without some delay. In this, Italy has been far more astute, and to the painter, who was born in 1856 in Florence to an expatriate couple from Philadelphia, it consecrated more than 20 years ago a fine exhibition, held at the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara. Under the title Sargent and Italy. it in fact recounted his many trips along the peninsula, focusing on the top destinations of Venice, Florence, Capri. Indeed, the essence of Sargent is that of a cosmopolitan artist, able to speak four languages: educated in Europe, a passionate traveler in the Mediterranean countries and linked to America thanks to wealthy patrons who commissioned him to do a variety of works. An Englishman by adoption, he never wanted to settle in the United States in which his origins were rooted, and as a true expatriate according to the canon created by Henry James (who was the founding example of this model of life and at the same time the one who best translated it into literature) he lived between the Old and New Worlds, with an irreducible and inalienable preference for the former, whose history he himself collected and revived through his artistic choices.

In Paris, Sargent entered Carolus Duran’s atelier and the École des Beaux-Arts, studying, thanks in part to trips to Spain and the Netherlands, the great masters of the early modern age. His masters of choice became Velazquez, Hals and then van Dyck, with upstream, thanks to their mediation, Titian. It was this profound homage to the tradition of European portraiture that placed Sargent in a line of continuity capable of gratifying the aspirations of his potential clients and posing himself as the decisive guarantee of a crack-free fortune among the exponents of the old aristocracy of titles and the new aristocracy of money, between the two sides of the Atlantic. Re-doing the Old Masters was at first a duty and an apprenticeship for him, then a strategic decision, not unlike exhibiting a portrait and a landscape or composition painting every year at the Salon. It was not, at any rate, a matter of mere imitation, but of a reinvention of the portrait genre, supported by a superfine technique, a vibrant freedom of touch, which distinguish at first glance Sargent from his master Duran, as can be grasped in the exhibition by comparing the pupil’s early results and those, suggestive but in comparison more anodyne, such as The Lady with the Glove of the latter (Musée d’Orsay).

Sargent thus had an academic training, which we see documented by studies and copies, and for many critics he always remained an academic painter, when even seduced by Manet and Monet, with whom he forged fruitful relationships. But, if we are to label him in this way, he was an academic of genius, versatile and intelligently attentive to intercepting the taste of the environment in which, as a foreigner, he began to establish himself. This academic substratum of his vision shines through in Fishing for Oysters at Cancale (Washington, National Gallery of Art), intended to satisfy the good taste of the Salon audience: the scene of Breton women fishermen crossing the sunny beach becomes the pretext for organizing a composition skillfully structured in the relationship between figures and background and for creating those liquid and mobile plays of light that were to become the artist’s signature. It is, moreover, a faux en plein air, because only some figures are studied on the spot, while the painting as a whole is conceived in the atelier. The discerning observer who is not easily seduced will find true satisfaction elsewhere. So it is in the small paintings and watercolors made during his travels to Spain and Morocco, places that Sargent loved deeply and of which he left us an endless pictorial record, that we grasp a very high quality, at least for what the Paris exhibition offers us: not so much and not only in the famous Smoke of Grey Amber (Williamstown, Clark Art Institute), but the two glimpses of Moroccan cities and especially in theAlhambra (private collection), in which the painter perfectly renders the corrosive action of light on the ochre stone of Granada, in the torpor of the affected air. From these Iberian excursions Sargent brings back ideas for exotic and ambitious paintings, culminating in El Jaleo (1882), for which his Boston patroness, Isabella Stewart Gardner, had a new court built in her Fenway Court mansion so that it could be worthily exhibited. The painting is the great absentee in this exhibition.

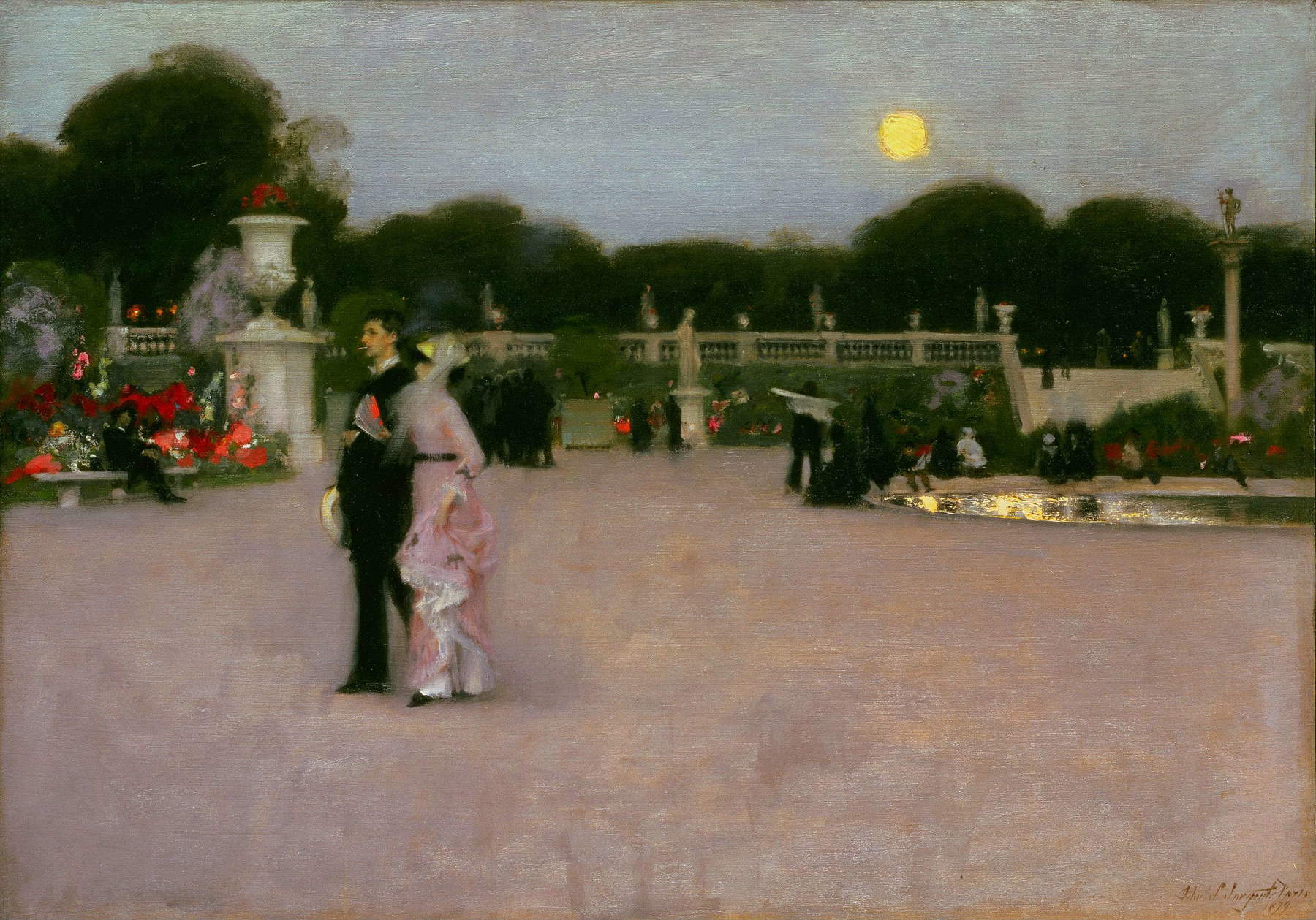

With the different formats and breadth of subjects Sargent fascinates with the plurality of levels in which he can be read, beyond the magnificence, known to most, of the portraits. In the Jardin du Luxembourg (Philadelphia Museum of Art) there reigns a somewhat rarefied and melancholy atmosphere worthy of a tale by Anatole France or of those that make up The Pleasures and Days of the Young Proust. The pearly veil shrouding the evening, which has something of Whistler about it, is kindled by touches of vermilion color from a few floral spots, and the disc suspended mid-sky of the full moon drops golden drops into the pool of water. This search for virtuoso and never trivial effects of light, one among the elements that denote the comparison with French colleagues, makes Sargent always recognizable: in theVenetian Interior (Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museum of Art) the originality of the painting lies entirely - even more than in the oblique cut imprinted on the composition - in that diagonal strip of sunlight that slices through the bare, gray floor as if glazed by Manet’s brushstrokes.

Thanks to that exceptional showcase that is the Salon, Sargent gradually made his way into the Parisian scene, beginning to immortalize members of the local society and Americans who had moved to France. Some portraits of the late 1970s appear as attempts to find his own personal mark in a genre in which everyone competes, but he eventually reaches his goal. In the Portrait of Édouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron (Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections), the hypnotic fixity of the little girl, around whom the whole painting revolves, and the defiant gaze of her brother impresses, in this ability to renew van Dyck’s late 19th-century portraits of children and adolescents, on this side of an equal, scenic red curtain. It is the dominant color of the Portrait of Dr. Samuel Pozzi (Los Angeles, Hammer Museum), which the general public is also (and perhaps especially) familiar with thanks to the book by English writer Julian Barnes(The Man in the Red Robe). In this image of private life raised to solemnity and grandeur is not only eternalized the charm of a doctor of the time, a well-known socialite and an avid womanizer, but is synthesized all the allure that, passing from the feminine to the masculine sphere, emanates from the Belle Époque. Even more intriguing is Edward Darley Boit’s Portrait of Daughters (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts): no less columnar than the huge Oriental vases in the background, the four little girls-sort of variants of a single type taken at somewhat different ages-emerge from a blanket of darkness and gaze at us similar to those apparitions that dot the ghost stories of James, who was among Sargent’s earliest and most ardent admirers. Of course, the exhibition includes more than just masterpieces. Some paintings, sometimes of sustained or sometimes discontinuous quality as they are less committed, focus on friends and colleagues, such as Fauré, Rodin, Helleu and Monet; the latter captured while painting en plein air.

Finally, with the presence of the portrait and some studies related to the face of his friend Albert de Belleroche, who in profile and somewhat disdainful expression so much resembles Madame Gautreau, we delve into the mystery of the birth of Madame X’s portrait and how Sargent was fascinated by a physiognomy that transcends from male to female and vice versa, with an ambiguity that only painting can enhance or completely undo.

In the years that followed the uproar caused by the famous painting Sargent was among the main promoters of a subscription aimed at the French state’s purchase of Manet’sOlympia, which at the time of its first exhibition had caused an even greater scandal. Soon afterwards it was Sargent’s turn, with The Carmencita marking a fleeting but dazzling comeback for the Parisian Salons, being acquired in 1892 (it is now in the Musée d’Orsay). This large portrait, again inspired by the Spanish world, closes the exhibition.

With his departure for London in 1886 Sargent left the field open to Giovanni Boldini and the triumph of those feminine beauties we all know. Who knows how the two magnificent portrait painters would have contended in the Parisian square, had they fought side by side in the thicket of their aristocratic clientele. It was with both of them that the archetypal female glamour was born, blending beauty, taste and haute couture, and which transmogrified from the field of painting into that of glossy magazines in the decades to come. The pages of a 1999 issue of Vogue show a beaming Nicole Kidman whom Steven Meisel’s lens clad in model-inspired clothes and photographed in the same poses as Sargentian icons. This aspect of mass culture also belongs to the artist’s fortune, but it captures only its brilliant surface. In the variety of genres, techniques, and media used, Sargent is a well-rounded artist, who-beginning with the fantastic watercolors that a 2017 exhibition at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery nicely showcased-must be discovered in detail and as a whole. On the day he decided to call it quits with Paris, he had turned 30 and created some of his masterpieces, including that Madame X he would later call “the best thing I have done.” He was leaving behind the capital that had launched him and then in time forgotten him, but not the success that would chase him to his death.

The author of this article: Mauro Minardi

Mauro Minardi è uno storico dell'arte che si occupa in prevalenza di pittura italiana del tardo Medioevo e del Rinascimento, alla quale ha dedicato libri e numerosi saggi. Nutre altresì vari interessi sulla storia della cultura, la storia del collezionismo a cavallo fra Ottocento e Novecento e le relazioni tra arti figurative e letteratura nello stesso periodo, argomento al quale ha dedicato il suo ultimo libro (Come la bestia e il cacciatore. Proust e l'arte dei conoscitori, Officina Libraria, 2022).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.