When last May Palazzo Reale in Milan announced its collaboration with London’s Tate Britain to mount an exhibition entirely dedicated to the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Pre-Raphaelites. Love and Desire, great curiosity was created around the exhibition: after all, the fascination with medieval modernity that characterizes those paintings and drawings seems unquestionable. The two terms “modernity” and “medieval” juxtaposed might seem an oxymoron, but in fact it is the most fitting juxtaposition by which this movement born in England in the mid-nineteenth century, around 1848, thanks to the revolutionary project of seven students of the Royal Academy that led them to form a brotherhood. The latter rejected academic art, thus the milieu from which they came, and the " Raphaelites ," the followers of Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520), in favor ofmedieval art whose themes and styles were nevertheless accompanied by the idea of representing reality and nature as they were.

Their very name of “Pre-Raphaelites” pointed to the era before the Urbino painter as their model of art, since the latter, especially with his Transfiguration, had in their view distorted the principles of simplicity and truth in his paintings : too much virtuosity, a misplaced pomposity of the characters depicted, and a lack of adherence to the truth of nature. As John Ruskin, mentor of the Pre-Raphaelites, put it, their painting responded to “the need to return to ancient honesty,” or so-called primitivism, “regardless of any conventional rules of painting”: through pure color, the importance of the contour line and the search for symbolic space, the Pre-Raphaelites found in the Middle Ages the right tools for a renewal of language and content.

It is from this premise that the Milan exhibition moves along an exhibition path whose intent is to present to the public the characteristic themes of the movement’s entire poetics and the fundamental influence of pre-Renaissance Italian culture and art.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Pre-Raphaelites. Love and Desire |

|

| Pre-Raphaelites Exhibition Hall. Love and Desire |

|

| Pre-Raphaelites exhibition hall. Love and Desire |

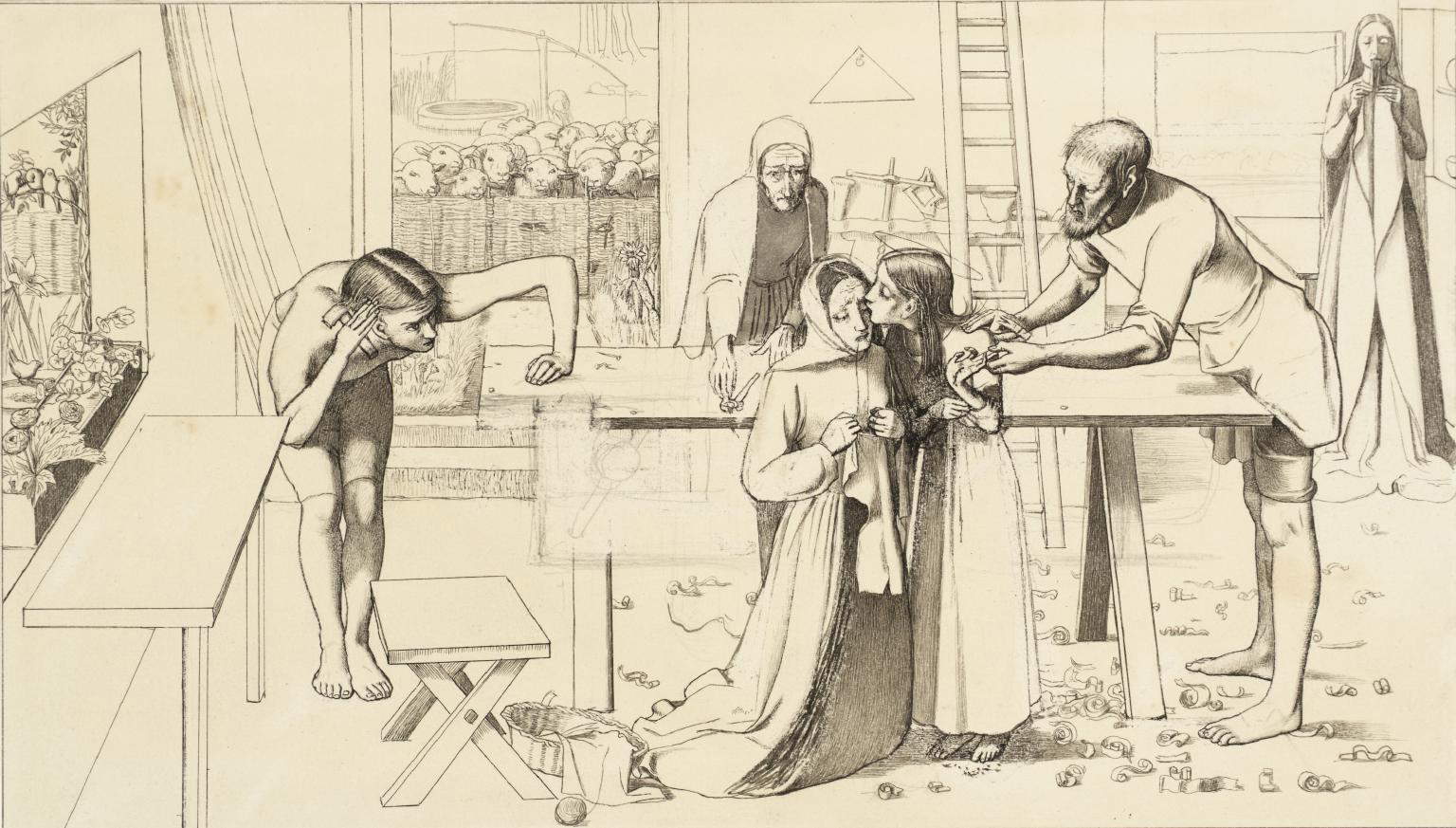

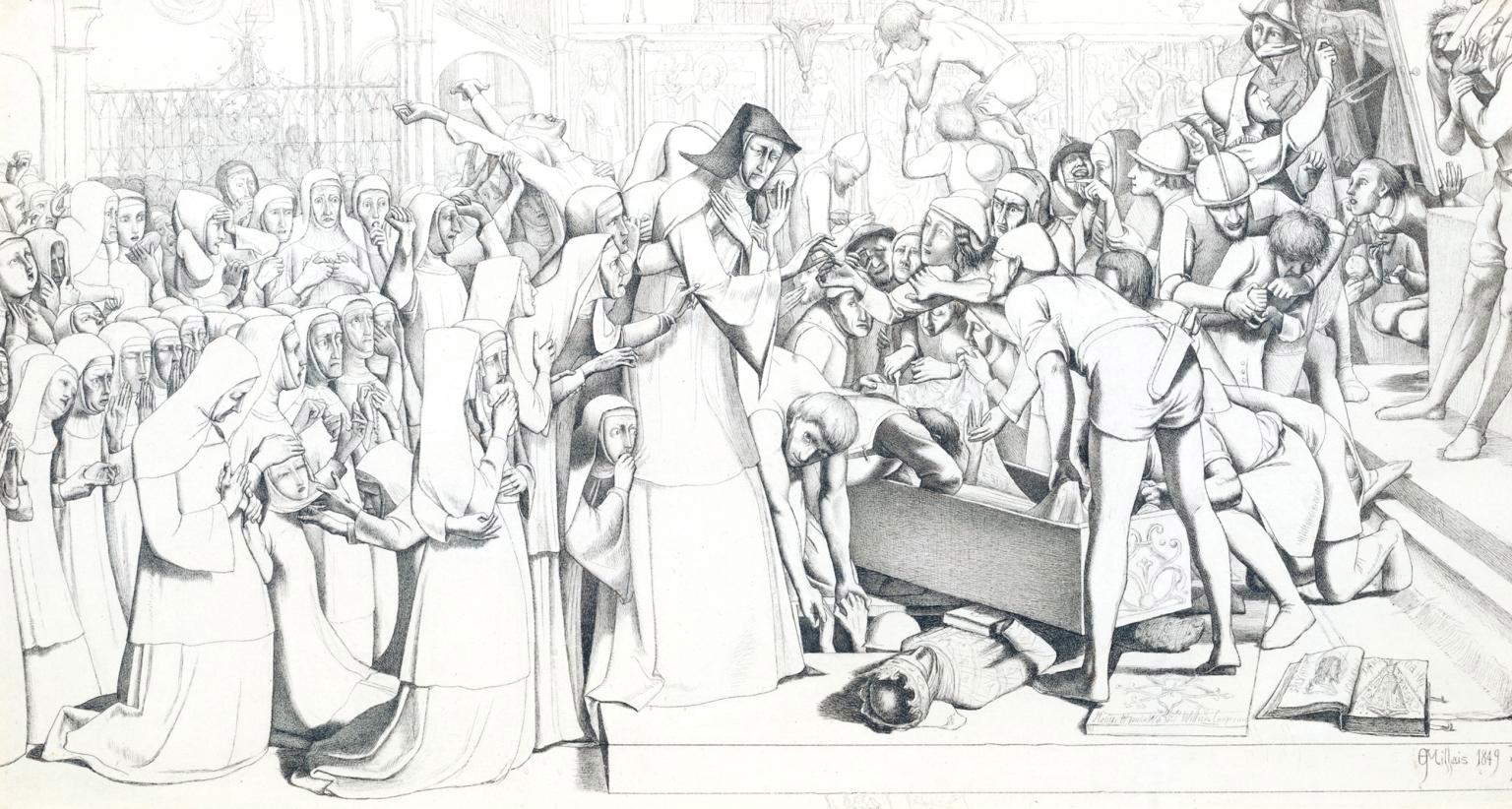

For thefirst time in Milan, iconic paintings of Pre-Raphaelism, such as TheOphelia by John Everett Millais (Southampton, 1829 - London, 1896), April Love by Arthur Hughes (London, 1832 - 1915), and the Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse (Rome, 1849 - London, 1917), works that hardly leave British borders: in this sense the exhibition is an unmissable opportunity to see paintings brought together that can only be admired together if you visit the famous London museum from which most of the masterpieces on display come. But at this point a debated question arises: how useful for cognitive purposes is an exhibition that relies on moving some eighty works from their location to give everyone a chance to admire them in another country? Certainly the excitement of being able to contemplate masterpieces of British art history up close is extraordinary, but in the writer’s opinion they have been brought together in an exhibition that adds no new insights or reflections or special details to what was not already known to those who visit it already possessing a general knowledge of this movement. Even the exhibition catalog itself offers only two essays that first illustrate the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and then the relationship between the Pre-Raphaelites and Italy. Maria Teresa Benedetti, in her contribution, states that John Ruskin himself, an English scholar who “guided the Pre-Raphaelite artists to an understanding of the beauty of our Italian architecture, painting and landscape,” had expressed passion for our country. In addition, from the late 18th century, Italian art spread in England mainly through numerous reproductions of Italian works of art, particularly through engravings of the medieval frescoes in the Pisa Cemetery made by Carlo Lasinio (Treviso, 1759 - Pisa, 1838) in 1812, reproductions of the Florentine masters made by William Young Ottley, and chromolithographs by theArundel Society, as well as through illustrated books and repertories. Millais possessed a copy of the volume Pitture a fresco del camposanto di Pisa published in 1832; evidence of this is Millais’s study for Christ in His Parents’ House from about 1849: the study is the basis and model for the painting, but he made a scene of daily life from Jesus’ childhood and a composition in which the family seems to expand from the central figure of Christ. Or again in The Unburying of Queen Matilda, a crowded and detailed graphic work that the same artist completed in 1849 by highlighting outlines and avoiding the use of strong chiaroscuro and shaded shadows. The subject of the drawing is taken from Agnes Strickland’s Lives of the Queens of England: the protagonist is Matilda, wife of William the Conqueror, both of whom are buried in Holy Trinity Church in Caen. In 1562 Calvinists occupied the city and plundered the royal tombs, stealing Matilda’s jewels. The scene is depicted by Millais, who emphasizes details and gestures of the characters depicted, especially the nuns whose faces express great despair at what is happening. These are associated with the figures of saints and martyrs visible in the decorations on the wall behind.

|

| John Everett Millais, Study for Christ in His Parents’ House (ca. 1849; graphite on paper, 19 x 33.7 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| John Everett Millais, The Unearthing of Queen Matilda (1849; ink on paper, 22.9 x 42.9 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

As already stated, the exhibition takes the visitor through the most characteristic themes of Pre-Raphaelism: from poet painters to secular faith, from loyalty to nature toromantic love, from the beauty of soul and body to myth. The section, found in both the exhibition itinerary and the catalog, of the biographies of all eighteen artists who took part in the Pre-Raphaelite movement is very useful as this provides a cultural and experiential contextualization of their art: one finds here the names of the movement’s best-known exponents, such as Edward Burne-Jones, Arthur Hughes, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John William Waterhouse, and of the somewhat lesser-known exponents, such as John Brett, Philip Hermogenes Calderon, Charles Allston Collins, and Frank Cadogan Cowper, but nonetheless all linked to a way of painting from which great masterpieces of British art resulted.

One of their intentions was to produce art that had a similar quality to the literary works of their favorite writers, including Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Romantic writers such as Alfred Tennyson, as well as Dante Alighieri , who greatly influenced the art of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (London, 1828 - Birchington on Sea, 1882): he translated the works of the famous poet, and his father was also a Dante scholar, so much so that he named his son after him. Among the favorite themes that the Pre-Raphaelites liked to find in their readings and wished to transpose into their pictorial works was tragic and romantic love: stories of infidelity, of young lovers belonging to different walks of life who were therefore hindered by their respective families. Their readings were therefore inspiration for their paintings, but to this they added painting from life; in this way they could paint, for example, every detail of natural elements, such as foliage, flowers, grass, and often serving as models for human figures were friends and family members. In fact, the poet and painter Elizabeth Siddal (London, 1829 - 1862) is frequently found in Pre-Raphaelite paintings: she began posing for them since the painter Walter Deverell (Charlottesville, 1827 - London, 1854) met her at a milliner’s where the young woman worked, but the most famous female character she played was that of Ophelia in the work of the same name created by Millais. The artist was inspired by Shakespeare’sHamlet, but while the writer has Queen Gertrude recount Ophelia’s tragic end from a distance, Millais intimately takes the viewer to the place of the girl’s death. To create the painting, the artist moved for five months to the vicinity of an area dominated by greenery where the Hogsmill River flowed so that he could carefully observe the muddy water and foliage that were to accommodate thetragic scene of Ophelia’sdeath by drowning ; once back in London, he had the model Elizabeth Siddal pose for hours lying in a bathtub, dressed as a bride: in this way he could carefully observe the effect of the girl’s hair in the water and the dress that wetly adhered to her body. Every leaflet, every flower petal, every blade of grass was made individually by the artist, with profound accuracy; note the small bouquet of colorful flowers that Ophelia clutched in her hand and that because of her death is scattered in the water.

A close and intimate scene is also depicted by William Hunt (London, 1827 - 1910) in Claudius and Isabella, a painting inspired by a subject from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure . Claudius is sentenced to death for adultery and is asking his sister to break her vows as a nun by meeting Angelo, the duke’s vicar who has the power to release him from his sentence. The centerpiece of the scene is Isabella’s hands resting on Claudio’s chest: as she ponders the chance she has to help her brother by sacrificing her own monkhood, she feels Claudio’s heart, a symbol of life, beating. The latter, on the other hand, touches the chains that hold him captive. Much care has also been devoted to the young man’s velvet and fur dress.

|

| John Everett Millais, Ophelia (1851-1852; oil on canvas, 76.2 x 111.8 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| William Holman Hunt, Claudius and Isabella (1850; oil on panel, 75.8 x 42.6 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

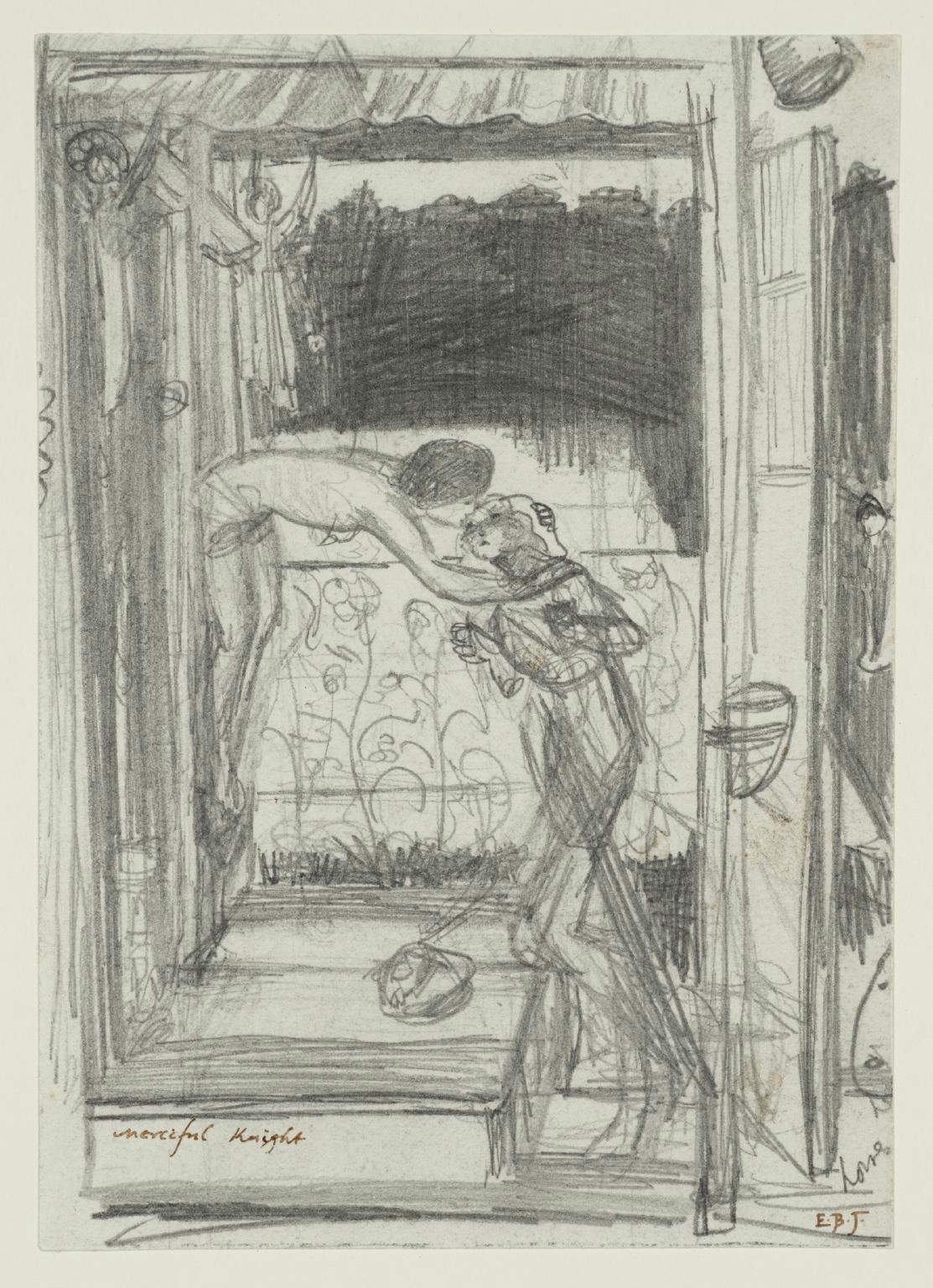

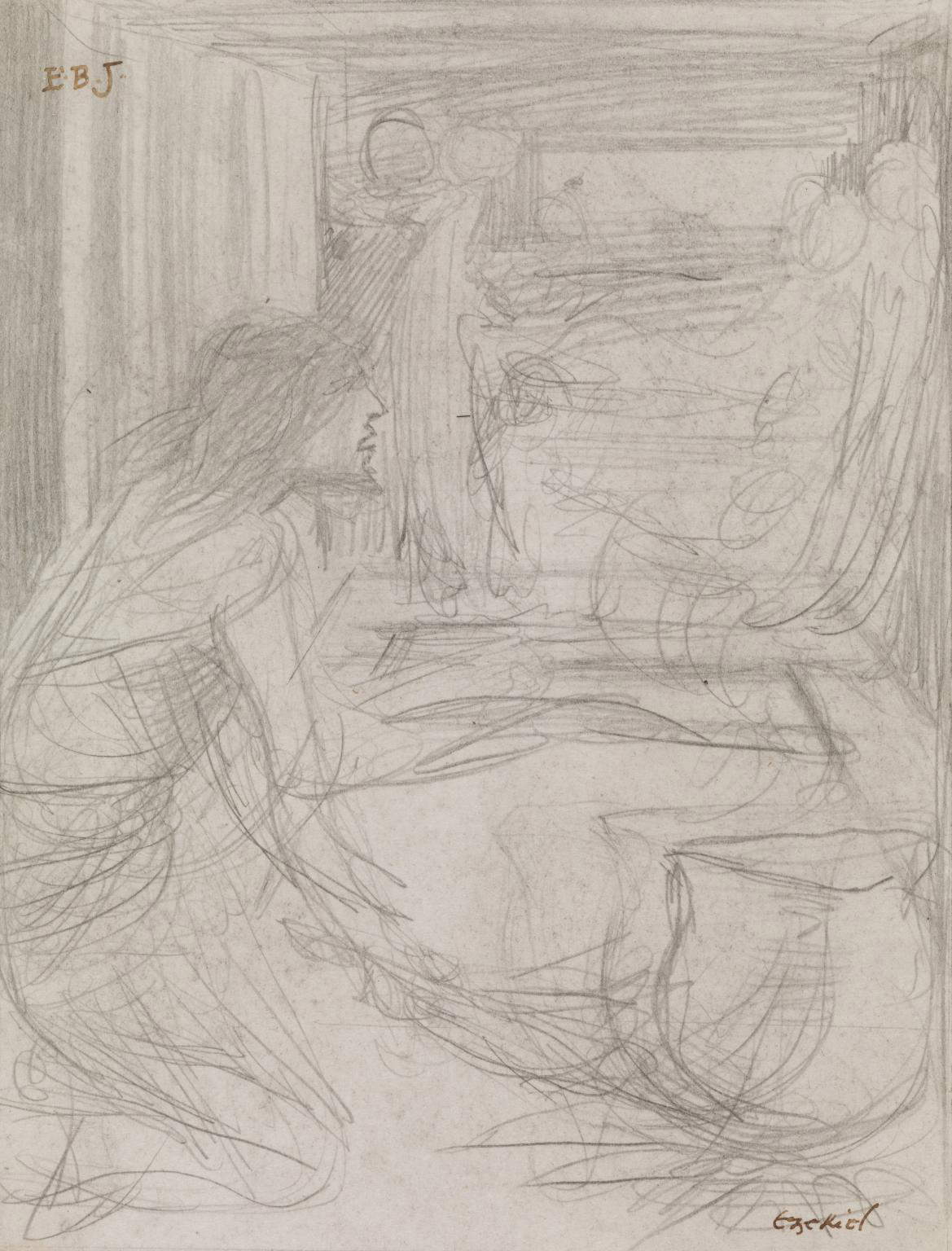

Also dear to the Pre-Raphaelites were biblical subjects, which, however, were met with criticism in Protestant Britain on the grounds that these paintings expressed a closeness to the Catholic tradition or in some cases the biblical figures were depicted too realistically, as in the case of the muscular Christ in Jesus Washes the Feet of Peter by Ford Madox Brown (Calais, 1821 - London, 1893). However, the Pre-Raphaelites renewed British religious painting by depicting characters with strong psychological expressiveness: in particular, Edward Burne-Jones (Birmingham, 1833 - London, 1898) made a series of drawings where he wanted to experiment with the expression of characters’ emotions through their different poses. On display are studî for the depiction of Ezekiel in Ezekiel and the Boiling Pot: the prophet was prevented by God from expressing his grief over the death of his wife; despite being far from the woman’s deathbed, the prophet imposes his presence. Various studies focus on Ezekiel’s hand holding the spoon to stir what is inside the pot; in fact, it is precisely the strokes in which the artist traces the pot and the prophet’s robe that express his restlessness and grief over the death of his dear wife. Also among Burne-Jones’s favorite volumes was the collection of stories on the theme of Christian chivalry The Broad Stone of Honour, in which central is the moment when St. John Gualbert is embraced in gratitude by the wooden Christ of a devotional shrine: a study for The Merciful Knight is on public display here.

In addition to biblical subjects, the Pre-Raphaelites depicted subjects of their contemporaries whose task it fell to them to express issues typical of their time, such as the socio-economic situation of women, the care and education of children, and unhappy romantic relationships. Dealing with the latter theme is one of the most striking paintings in the exhibition that hardly leaves the borders of Britain, Arthur Hughes’ April Love. A young woman, clad in a long, deep blue dress that stands out among the green foliage, mourns an ended love affair under an arbor looking away, while the man holds the maiden’s hand in his own: the meaning of the painting is explicitly suggested by the language of flowers, as the blossoming love expressed by the lush lilacs beyond the arbor is withered like the rose petals scattered instead in the foreground; the ivy and the rose ironically allude to eternal love. This painting was accompanied by some verses by the poet Alfred Tennyson that read “Love becomes a vague regret / We bathe our eyes with vain weeping. / By futile vexations bound we are / still.” As in the paintings with biblical subjects, even in the works with subjects drawn from contemporary life, the characters are charged with realism and psychological complexity. Loaded with expressiveness, for example, is the little girl protagonist of the watercolor Bad Subject, by Ford Madox Brown: a somewhat listless pupil who turns her gaze to the viewer, almost defying him.

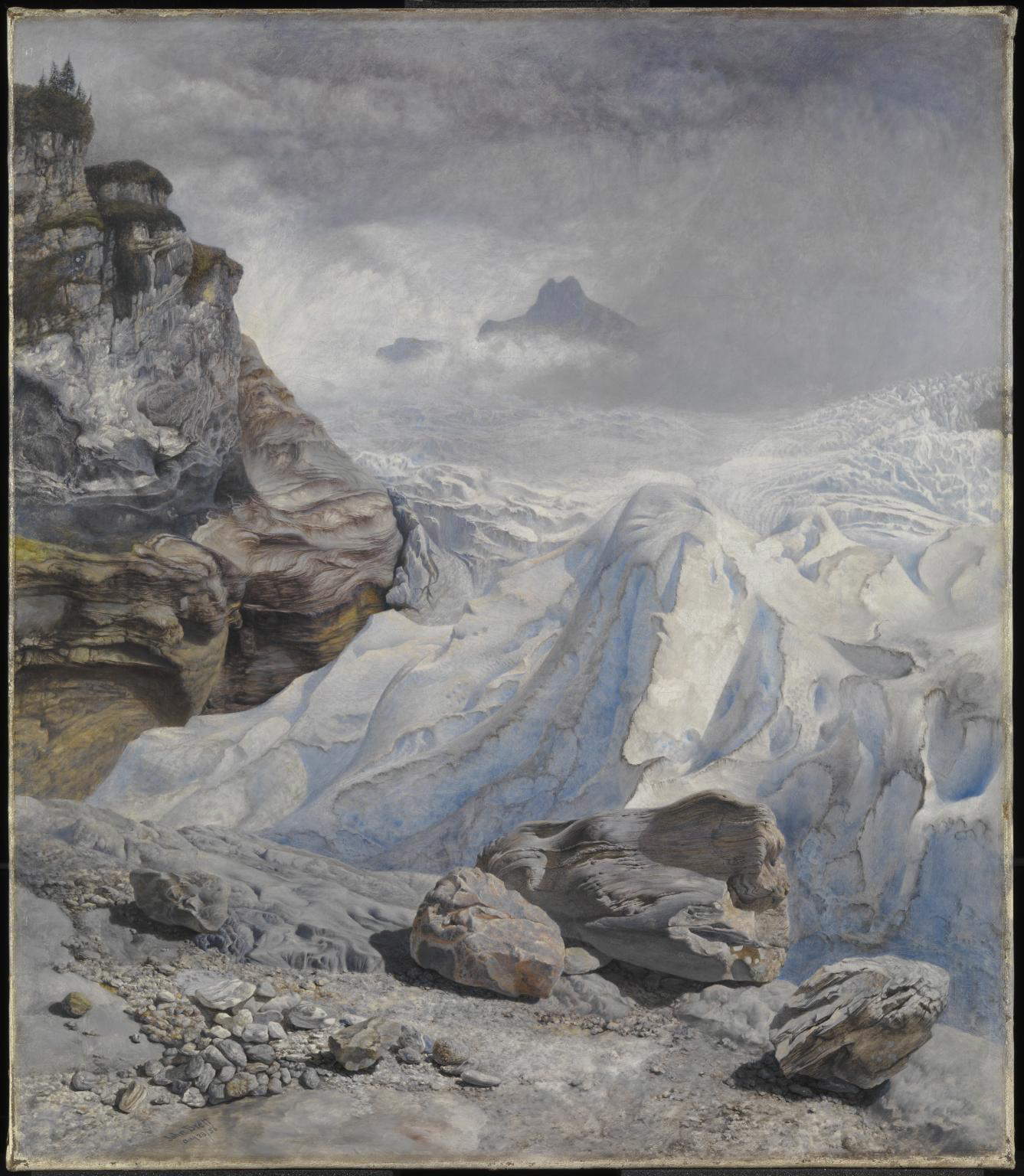

Thanks to John Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelites took to depicting nature as it was, as their advocate firmly believed in nature as God’s work of art, in which emotional and spiritual truth could be found. “Go forth to meet nature in total simplicity of heart [...] without discarding or selecting or despising anything,” Ruskin stated. Particularly embracing this naturalistic aspect was John Brett (Reigate, 1831-London, 1902): His are the spectacular Rosenlaui Glacier and the majestic English Channel as seen from the cliffs of Dorset, as well as the View of Florence from Bellosguardo, in which the artist depicts in detail the towers, domes and roofs of the city, which critic Allen Staley considered “one of the most extraordinary Pre-Raphaelite paintings, the nineteenth-century equivalent of the elaborate and detail-rich urban views of Canaletto and Bellotto.” By contrast, themore spiritual aspect of nature is expressed in Robert Braithwaite Martineau ’s Picciola (London, 1826 - 1869): the scene depicted in the painting is taken from Joseph-Xavier Boniface’s novel of the same name; a French convict soldier, Count Charney, cares for a seedling that has grown among the prison yard slabs. This is meant to emphasize that it is possible to find spirituality even in the simple observation of nature.

|

| Ford Madox Brown, Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet (1852-1856; oil on canvas, 116.8 x 133.3 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Edward Burne-Jones, Composition Study for The Merciful Knight (c. 1863; graphite on paper, 25.2 x 15.3 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Edward Burne-Jones, Composition Study for Ezekiel and the Boiling Pot (c. 1860; graphite on paper, 18.1 x 13.3 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Arthur Hughes, Love in April (1855-1856; oil on canvas, 88.9 x 49.5 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Ford Madox Brown, Bad Subject (1863; watercolor on paper, 23.2 x 21 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| John Brett, The Rosenlaui Glacier (1856; oil on canvas, 44.5 x 41.9 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| John Brett, The English Channel seen from the Dorset Cliffs (1871; oil on canvas, 106 x 212.7 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| John Brett, View of Florence from Bellosguardo (1863; oil on canvas, 60 x 101.3 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Robert Braithwaite Martineau, Picciola (1853; oil on canvas, 63.5 x 81.3 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, on the other hand, was particularly fascinated by the love stories of the medieval world, especially those told by Dante Alighieri or those of Thomas Malory’s Death of Arthur , but also those inspired by the famous Roman de la rose. The artist produced small-scale watercolors on these themes, characterized by an often collected and private setting: among them, The Tomb of Arthur, where Lancelot literally thrusts himself before the face of his beloved Guinevere at the very tomb of King Arthur, the latter’s husband; or the Marriage of Saint George and Princess Sabra, where the two lovers embrace in a tender embrace in which she cuts off a lock of hair with scissors and ties it to his armor and Saint George kisses her on the nose. Modeling for Sabra was Jane Morris, wife of the artist and writer William Morris, while the aforementioned Elizabeth Siddal, painter and companion of Rossetti, is found in the watercolor Paolo and Francesca da Rimini and in some drawings. Theillicit love of Paolo and Francesca, the famous couple featured in Canto V of Dante’s Inferno who fell in love while reading the love story of Lancelot and Guinevere, hints at the almost clandestine relationship between the artist and the model: the two later married in 1860. The work is divided into three parts: between the earthly kiss and the hellish embrace of Paolo and Francesca, Dante and Virgil shake hands while observing the two extremes of the tragic story of the two young lovers.

Continuing toward the conclusion of the exhibition are Dante Gabriel Rossetti ’s magnificent portraits of the seductive Pre-Raphaelite women who fully responded to the theories of theAesthetic Movement: beauty was to be represented in every art form. Rossetti knew Italian Renaissance painting and the portraiture of Titian, Raphael, Leonardo, and Michelangelo, and was strongly inspired by them: the female characters portrayed embody precisely modern beauty, with their thick, often red hair and marked facial features; even the rich fabrics and soft draperies of the dresses recall that ideal of ubiquitous beauty, so much so that the fashion of the time was inspired by the Pre-Raphaelite model. These are women who consciously dominate the entire canvas: clear examples are Aurelia (Fazio’s Lover), Mona Vanna, and Mona Pomona. The former is a subject inspired by a song by Fazio degli Uberti, which Rossetti had translated as His Portrait of his Lady, Angiola of Verona; notable here is the influence of sixteenth-century Venetian painting, from Titian to Palma il Vecchio to Veronese, whose works the artist saw in the Louvre. The most distinctive trait of this painting is the great sensuality it conveys, particularly through the gesture of styling her long wavy red hair as she turns her gaze toward the mirror: presumably in fact the painting is influenced by Titian’s Woman in the Mirror, a photograph of which Rossetti possessed. In this case Aurelia’s model was Fanny Cornforth, with whom the artist was having an affair.

Monna Vanna depicts a woman of inaccessible charm because of her imposing but distant beauty; however, what strongly attracts the viewer’s gaze is certainly the dress that dominates almost the entire scene. Very seductive are the bejeweled hands on which the protagonist weaves and rolls the necklace of red stones. In addition, the influence of Italian portraiture is also strong in this painting: the large sleeve refers to Raphael ’s Portrait of Joan of Aragon housed in the Louvre and Raphael ’s Veiled in the Pitti Palace.

Model Ada Vernon, on the other hand, was made the protagonist of the portrait of Mona Pomona: the woman embodies Renaissance beauty richly adorned, adorned and bejeweled; it is a painting that engages all the viewer’s senses because of the presence of the apple, flowers, and pearls. The sensuality is tangible in the hand gestures and expression, as a woman aware of her seduction.

Literary characters also embodied the ideals of beauty, such as Dante Alighieri ’s Beatrice in Beata Beatrix; however, in this case there is a direct reference in the painting to Rossetti’s life, as the artist created this evocative work in memory of his Elizabeth, who died prematurely at a young age. This masterpiece is imbued with symbolic meanings: the red dove, an allusion to the Holy Spirit and to love, offers a poppy to the woman, a flower that alludes to passion but also to death; the predominant red color in Beatrice’s hair, in Amore’s cloak and in the dove refers to human passion but also to spiritual intensity. The sundial pointing to nine o’clock is a literary reference to Dante’s Beatrice since Dante meets her at the age of nine and Beatrice dies at nine o’clock on June 9, 1290: within the composition of the painting, however, the sundial links woman to light, thus Beatrice is light. And again references to life and rebirth are caught in the wall in the foreground that divides an earthly area from a transcendent one, in the well behind Dante, in the flowering tree. For Rossetti, love was a union of earthly feeling and religious ecstasy, and indeed earthly and spiritual elements coexist in this work.

Pre-Raphaelite women began to be portrayed in the late 1880s as women protagonists of myths and legends where magic, enchantment, and curse were central: the heroines depicted were femmes fatales involved in a mysterious world. It wasJohn William Waterhouse in particularwho favored this theme; one of his most famous masterpieces is The Lady of Shalott, which, as its title suggests, is inspired by Alfred Tennyson’s romantic poem of the same name. The protagonist is a woman who lives in a tower on the island of Shalott, near Camelot, and because of a curse she is forced never to look toward that place or she will die. She looks outward through a mirror and weaves what she sees onto a magical cloth. One day, seeing Lancelot from her mirror, she is overcome by the temptation to look directly through the tower window and her gaze turns to Camelot, at which point she decides to leave the tower and head to that place and embarks on a river singing sad words, doomed to die. Waterhouse depicts in his work the girl as she is already sitting in the boat that is sailing the river gradually going out.

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Tomb of Arthur (1860; watercolor on paper, 23.5 x 36.8 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1855; watercolor on paper, 25.4 x 44.9 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Elizabeth Siddal Braids Her Hair (c. 1855; graphite on paper, 17.1 x 12.7 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Marriage of Saint George and Princess Sabra (1857; watercolor on paper, 36.5 x 36.5 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Aurelia (Fazio’s Lover) (1863-1873; oil on panel, 43.2 x 36.8 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Mona Vanna (1866; oil on canvas, 88.9 x 86.4 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Mona Pomona (1864; watercolor and gum arabic on paper, 47.6 x 39.3 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix</em (c. 1864-1870; oil on canvas, 86.4 x 66 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

|

| John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott (1888; oil on canvas, 153 x 200 cm; London, Tate Britain) |

If the aim of the exhibition at the Royal Palace is to illustrate the favored themes of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, visitors will have a good grasp of it, not least through the interesting drawings on display, mostly by Burne-Jones, which help to understand the stages of making and studying a painting. As for the catalog, it takes up the exact division of the sections of the exhibition, introducing each of them with a brief introductory text, but the worksheets are missing in most cases.

It also recalls the exhibition Pre-Raphaelites. The Utopia of Beauty, which was held in Turin, at Palazzo Chiablese, from April to July 2014: a number of Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces were being brought to the Piedmontese capital from Tate Britain for the first time, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The Beloved (The Bride), which is not in the Milan exhibition, however.

What other Italian city will the Pre-Raphaelites be coming to for the first time in a few years?

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.