From the Paleolithic masters who painted the bison race in the Lascaux caves to the “dynamic” little dog in Giacomo Balla’s 1912 painting, painters have always dreamed of depicting movement. And they have often succeeded, thanks to tricks of perspective and spatial inventions. The Roman exhibition A mano libera. Animated Art and Cinema in Italy (1957-1977) sheds light on that particular, unrepeatable moment when the desire of centuries of research on the image to be wrenched from its eternal condition of staticity actually took shape successfully. And this, exactly in the two decades of Carousel (1957-1977), at the hands of sculptors, painters, photographers and graphic designers who exploited the techniques of animation cinema and those of the cartoon industry. Through low-tech devices of extraordinary inventiveness and, often, poignant, poor poetry.

Bruno Di Marino, top scholar of this niche (but valuable) trend in Italian art, has called together the experiences of thirteen authors. And he has collected sketches, backdrops, rodovets, storyboards and films (about thirty), to place them side by side with classic works of art, as in the case of the 1970s paintings by Bruno Ceccobelli (in the following decade among the protagonists of the return to painting in the so-called Roman School of San Lorenzo and here discovered for the first time as a cartoonist), to be read in parallel, or in intersection, with the 8 or 16-millimeter films scratched, drawn and colored before being put into the projector. And from there enlivened by light.

The princely section of the four compartments of the exhibition, open until Oct. 12 on the upper floor of the City of Rome’s Museo in Trastevere, focuses on works made for Corona cinema. The Roman production company of the Gagliardo brothers, identified in the Quality Awards of the Ministry of Tourism and Entertainment as the main source of funding, left a free hand to authors such as Magdalo Mussio, Claudio Cintoli, Rosa Foschi and Luca Patella so that they could make short films lasting about ten minutes and for a fee of one million lire. “The Gagliardo brothers as their only goal was to win the Quality Awards. It was as much as 12 million liras per short film and the maker was entitled to a small percentage,” Foschi reveals in the interview published in the book Arte e cinema d’animazione in Italia (Dario Cimorelli Editore, 226 pages in Italian and English, 30 euros), which came out together with the exhibition for which it also constitutes the catalog (although Di Marino and Giacomo Ravesi in their texts also quote extensively authors, such as Cioni Carpi and Giampaolo Di Cocco, who are not present in the exhibition). Manfredo Manfredi, Palermo-born (born in 1934), Roman by training (he studied set design at the Academy of Fine Arts in via Ripetta during the years of Toti Scialoja) and now Umbrian by adoption, in the book responds this way to the question about the short time required to make a ten-minute film work that usually required many collaborators and a year’s work: “There are many ploys I used at the time to optimize time and gain precious seconds. After doing some animation, for example, I would insert a still image, then maybe zoom in” on it, and “in some cases you could replicate the same sequence of drawings with variations.” Solo work, almost always, and with a thousand tricks to meet the challenge.

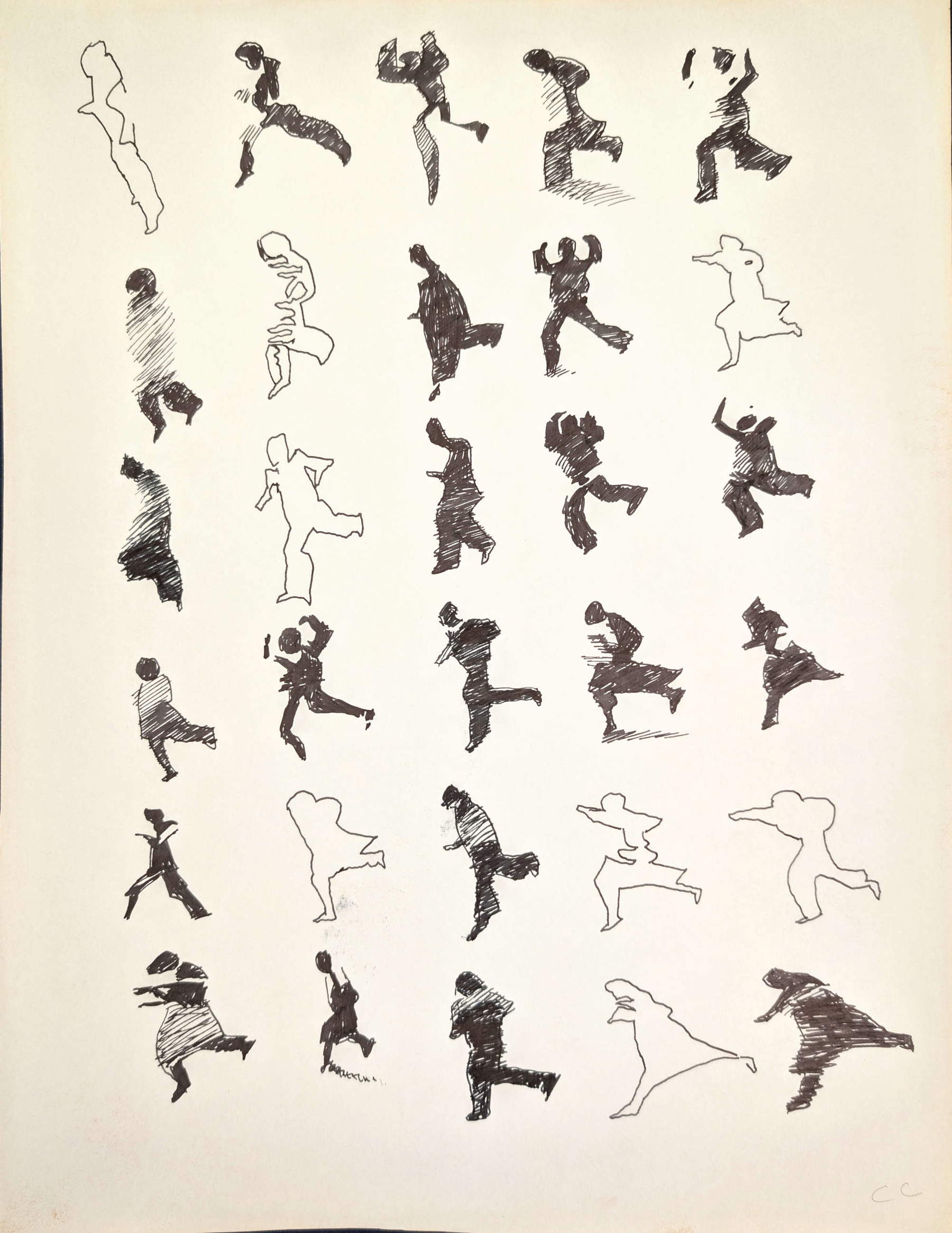

In the 1960s in which Italy was declining in its own way the language of Pop Art and, since 1967, was imposing itself on the international scene with theArte povera, a trend in which is inscribed the very brief and luminous parabola of Pino Pascali (1935-1968), who landed in museums and galleries after having animated many Carosello advertisements (the 1962 Salvador el matador commercial, for example), here was a handful of experimenters making a virtue of necessity and, of elementary means, an original filmic language. So it is with the political documentaryism of Manfredi’s Wall (1970, integral in the exhibition and on Youtube), present in the exhibition with the set design of the film, but also with coeval paintings, of a figuration assimilable to the style of Bruno Cassinari. By the author in 1969 of Ko (a docu-animation on the story of a boxer, the favorite subject of Titina Maselli’s paintings) a frame of Sotterranea from 1971 is also exhibited, in which photography is integrated with drawing, particularly at the moment when a large photographic poster with the face of a seductive model appears in the glass of the convoy to the subway traveler, so much so that it recalls the scene from Federico Fellini’s Temptations of Dr. Antonio. She is, that Manfredi mannequin, the ideal sister of Ursula from the famous Garden of the same name painted and assembled by Claudio Cintoli in 1965 in Rome for the Piper stage together with architects Capolei and Cavalli.

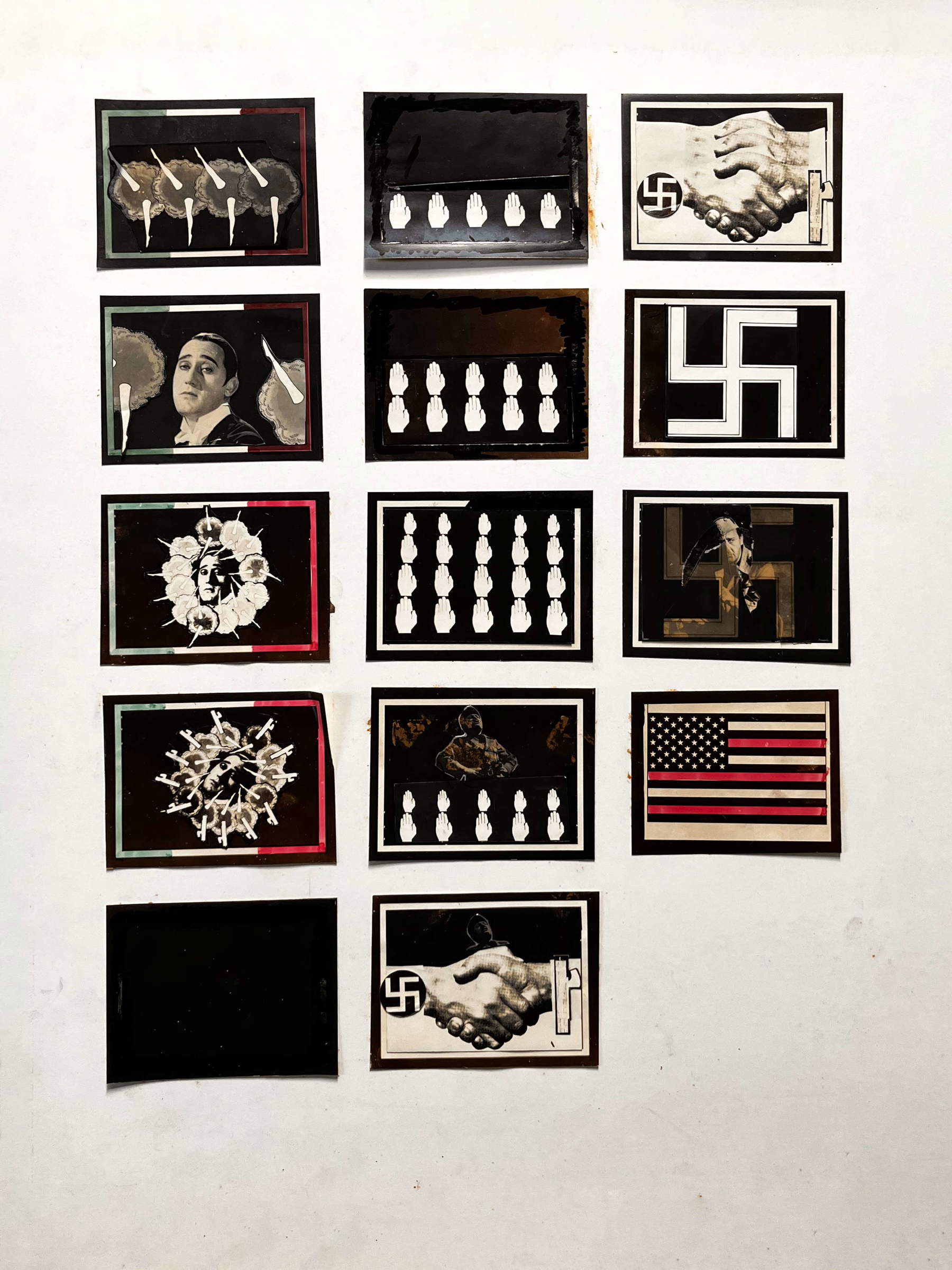

By the painter from the Marche region, several mixed media on paper from 1969(textures tuned to the painting of his friend Piero Dorazio) are on display, with Prati, Nuvole, Tartarughe; and the 35 mm Primavera nascosta, transferred to digital by the Cineteca di Bologna, among the main lenders to theRoman exhibition together with gallery owner Daniela Ferraria and the Frittelli arte contemporanea gallery in Florence, which have Pascali’s production for animation advertising (ink, marker and pencil drawings on paper and on acetates) in their collections.

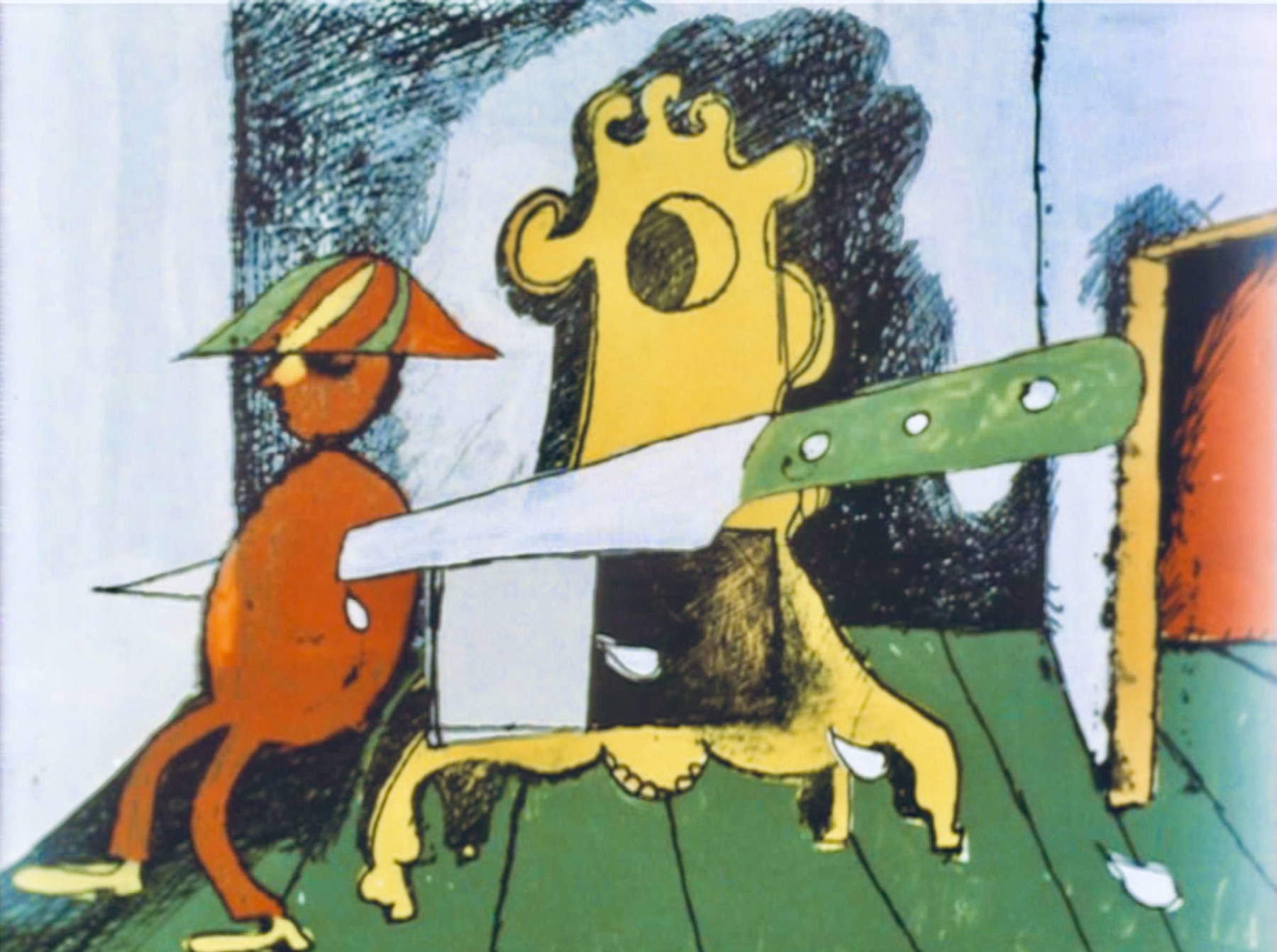

Cintoli and Pascali have, after all, passed through Fabio Sargentini’s Attico garage, a leading space of the Roman avant-garde, and not only, in the 1960s. To the art of experimentation and multimedia also belonged the figure of Luca Maria Patella here kept rightly distinct from the work of his wife, Rosa Foschi, although there were also continuous creative relationships between the two (Di Marino speaks of a “playful-conceptual” style for one and, for the other, of a “playful-poetic” approach). By Patella, in whom the conceptual imprint can be seen even in works of more immediate visual enjoyment, such as the beautiful photographic etchings of Colored Landscape (1966), intrigues and enchants the story of the same year entitled Who will comb me?

For the Corona production company also worked, we said, Magdalo Mussio, singular figure of graphic designer, painter and art director of Marcatré, a critical and avant-garde cultural magazine for which Cintoli also wrote. Mussio, moreover, was chosen by Di Marino for the book’s cover. His is in fact the rodovetro with the dragon, in India ink on acetate, designed for The Golden Bean in 1968: fairy tales and metamorphosis return, after all, in several works in the exhibition by more than one author/author.

Not only Rome (the city of cinema and ministries) and Milan (the capital of TV and advertising) are at the center of the zoom on the relationship between visual arts and animation cinema. Also important is Florence, represented in the exhibition by the figure of the Florentine Andrea Granchi, with his photographic collages and, same technique, stop motion Super 8s such as Cosa succede in periferia? (1971). And then the Veneto with Paolo Gioli, active between New York, Rome and Milan, suspended between photographic imprint (also translated in the oil works in the exhibition) and the pure abstraction of 16mm; and with Toni Fabris, a sculptor from Bassano del Grappa, son of art (his father, Luigi, also sculpted) and author in 1949 of the animated film Gli uomini sono stanchi proposed nine years later at the Venice Film Festival: to represent this, our, anguished existential condition of his, we see moving plasticine figurines where Fabris’s plastic research (who in ’66 will exhibit at the Biennale arte in Laguna) is documented by abstract and surrealist bronzes. Veronese, moreover, is the painter Marinella Pirelli, who lived between Rome and Milan (important acquaintance with Bruno Munari) and author in the early 1960s of two fairy-tale shorts such as Pinca e Palonca and Gioco di Dama, brought to the exhibition together with the cast of plasticine characters dressed in cloth, wool and fantasy.

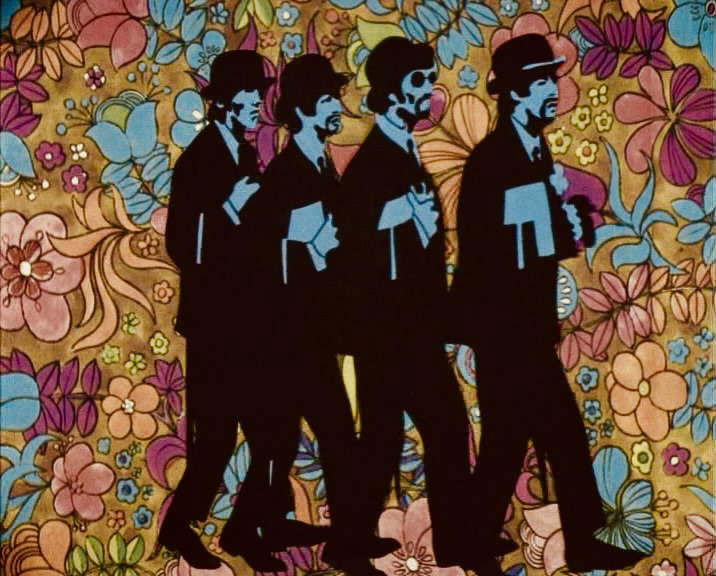

In the midst of so much avant-garde experimentation and creations for an audience of insiders (Rosa Foschi points out in the interview that “the shorts that won the Quality Awards” were screened at the cinema before the feature films, “and I remember well that people were puffing because they wanted to see the film right away”), the work of two masters known to the general public in theater and television. We are talking about set designer and illustrator Lele Luzzati, in this case paired with filmmaker Giulio Gianini. And of the painter Mario Sasso, made famous by the theme songs he made for RAI (about 130) in forty years of life and work for the studios of Viale Mazzini: exquisitely iconic, images to be cut out and framed, are the frames of his 1977 storyboards for the animation that introduced Il processo or Storia di un italiano, entrusted to the mask of Alberto Sordi and by now contaminated with electronic graphics. By Gianini and Luzzati we admire, finally but first and foremost, the ink drawings on acetate, and mixed media on paper, of The Thieving Magpie (1964) and Pulcinella (1973), which, children of Rossini’s music and, later, of the 1968 rebellion, mock power. And they do so with the grace of a refined, colorful folk dance. And with the archaic, irregular force of the folk sign.

The author of this article: Carlo Alberto Bucci

Nato a Roma nel 1962, Carlo Alberto Bucci si è laureato nel 1989 alla Sapienza con Augusto Gentili. Dalla tesi, dedicata all’opera di “Bartolomeo Montagna per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo a Vicenza”, sono stati estratti i saggi sulla “Pala Porto” e sulla “Presentazione al Tempio”, pubblicati da “Venezia ‘500”, rispettivamente, nel 1991 e nel 1993. È stato redattore a contratto del Dizionario biografico degli italiani dell’Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, per il quale ha redatto alcune voci occupandosi dell’assegnazione e della revisione di quelle degli artisti. Ha lavorato alla schedatura dell’opera di Francesco Di Cocco con Enrico Crispolti, accanto al quale ha lavorato, tra l’altro, alla grande antologica romana del 1992 su Enrico Prampolini. Nel 2000 è stato assunto come redattore del sito Kataweb Arte, diretto da Paolo Vagheggi, quindi nel 2002 è passato al quotidiano La Repubblica dove è rimasto fino al 2024 lavorando per l’Ufficio centrale, per la Cronaca di Roma e per quella nazionale con la qualifica di capo servizio. Ha scritto numerosi articoli e recensioni per gli inserti “Robinson” e “il Venerdì” del quotidiano fondato da Eugenio Scalfari. Si occupa di critica e di divulgazione dell’arte, in particolare moderna e contemporanea (nella foto del 2024 di Dino Ignani è stato ritratto davanti a un dipinto di Giuseppe Modica).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.