First exhibition of 2026 for the Alfonso Artiaco Gallery in Naples: it is dedicated to Achille Perilli (Rome, 1927 - Orvieto, 2021), one of the most rigorous and radical protagonists of Italian abstraction in the second half of the 20th century. Entitled simply Achille Perilli, it is also the first exhibition the gallery has dedicated to the artist. Scheduled to run from Jan. 19 to Feb. 28, 2026, the exhibition officially opens on Saturday, Jan. 17, starting at 11 a.m. and features a selection of works that can be traced back to one of the most intense, coherent and enduring cycles of the artist’s research, which began in the late 1960s and developed over the following decades.

The exhibition aims to offer an opportunity to reread Perilli’s work in the light of a theoretical and formal reflection that runs through his entire production. The works presented belong to a phase in which the painter more consciously elaborates a conception of form as a dynamic and unstable process, and of space as a conceptual dimension, never reducible to a mere support or place of representation.

To fully understand the scope of the cycle exhibited, it is necessary to recall the historical and theoretical context from which it originated. The experience of Forma 1, a group founded in 1947 by Perilli together with other artists and intellectuals, marks the beginning of a reflection that questions the very foundations of the figurative tradition. In that climate an idea of form is affirmed, not as an accomplished entity, but as a state of permanent tension, open to transformation and change. Form thus becomes the site of a productive conflict, a field of forces in which rational instances and irrational drives, constructive rigor and perceptual instability are measured.

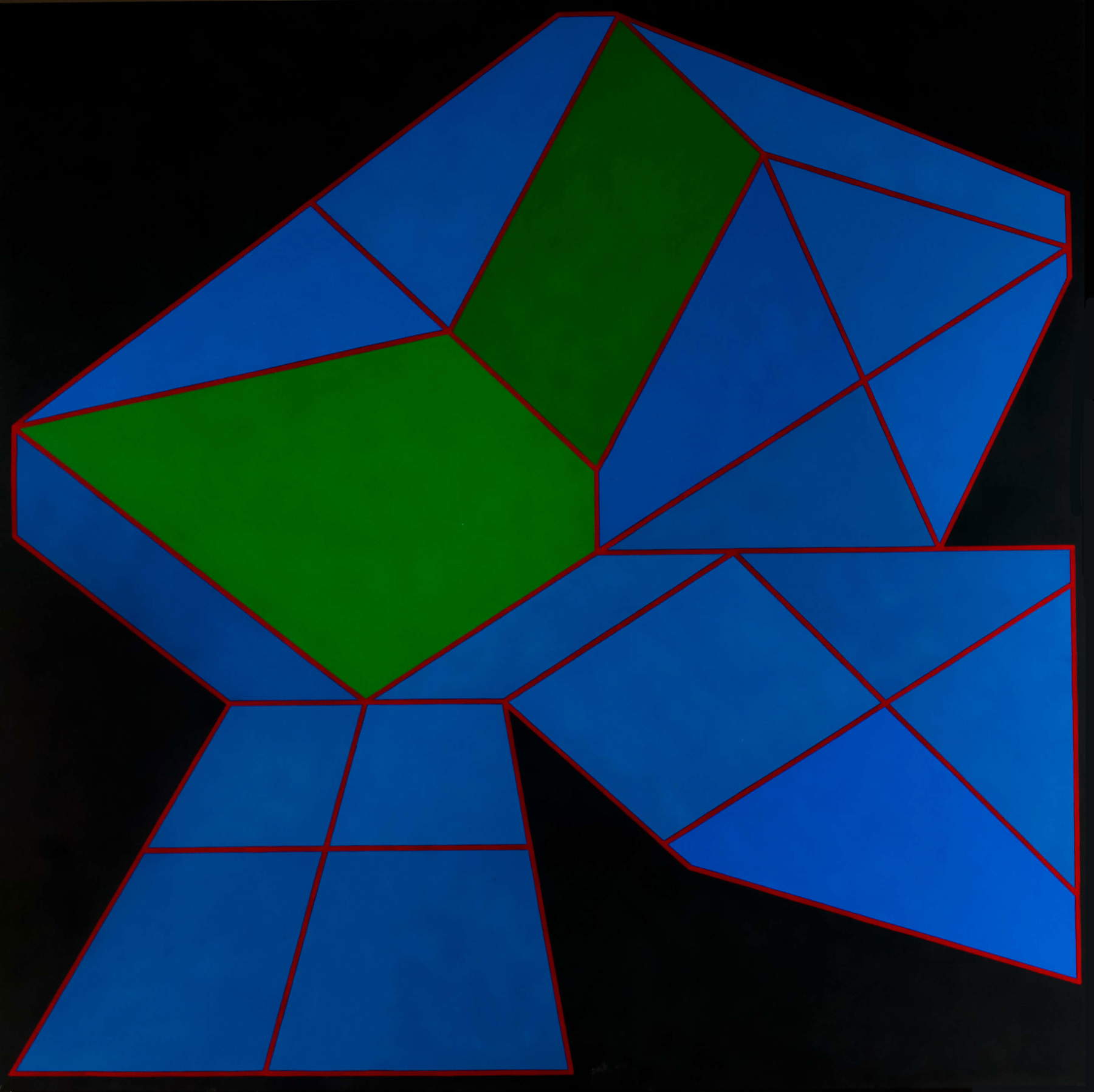

At the end of the 1960s, in a historical moment marked by the crisis of traditional perspective systems, Achille Perilli defined a theoretical position of great coherence, made explicit in the 1969 text Indagine sulla prospettiva (Investigation of Perspective). In this writing, perspective is radically questioned as a coercive device of the gaze, capable of imposing an ordered and hierarchical vision of space. In its place, Perilli elaborates an unstable arrangement based on the continuous interaction between color, sign, tone and structure. The work renounces offering a recognizable image or an identifiable space, reducing visual information until it is transformed into an open, ambivalent experience without a definitive solution.

It is precisely in this theoretical and operational transition that the notion oflabyrinth, a central element of Perilli’s research, is most clearly affirmed. The labyrinth is never understood as an iconographic subject or narrative figure, but as a constructive principle of the work. In the 1971 Manifesto of the Mad Image in Imaginary Space, the artist describes it as a configuration of simultaneous paths: “one can no longer accept any other law than that of its twisted unraveling into many paths all equal and all different.” In this vision, the usual spatial coordinates are suspended: high and low, inside and outside, object and distance lose meaning, while each element of the work becomes at once eye, space and form.

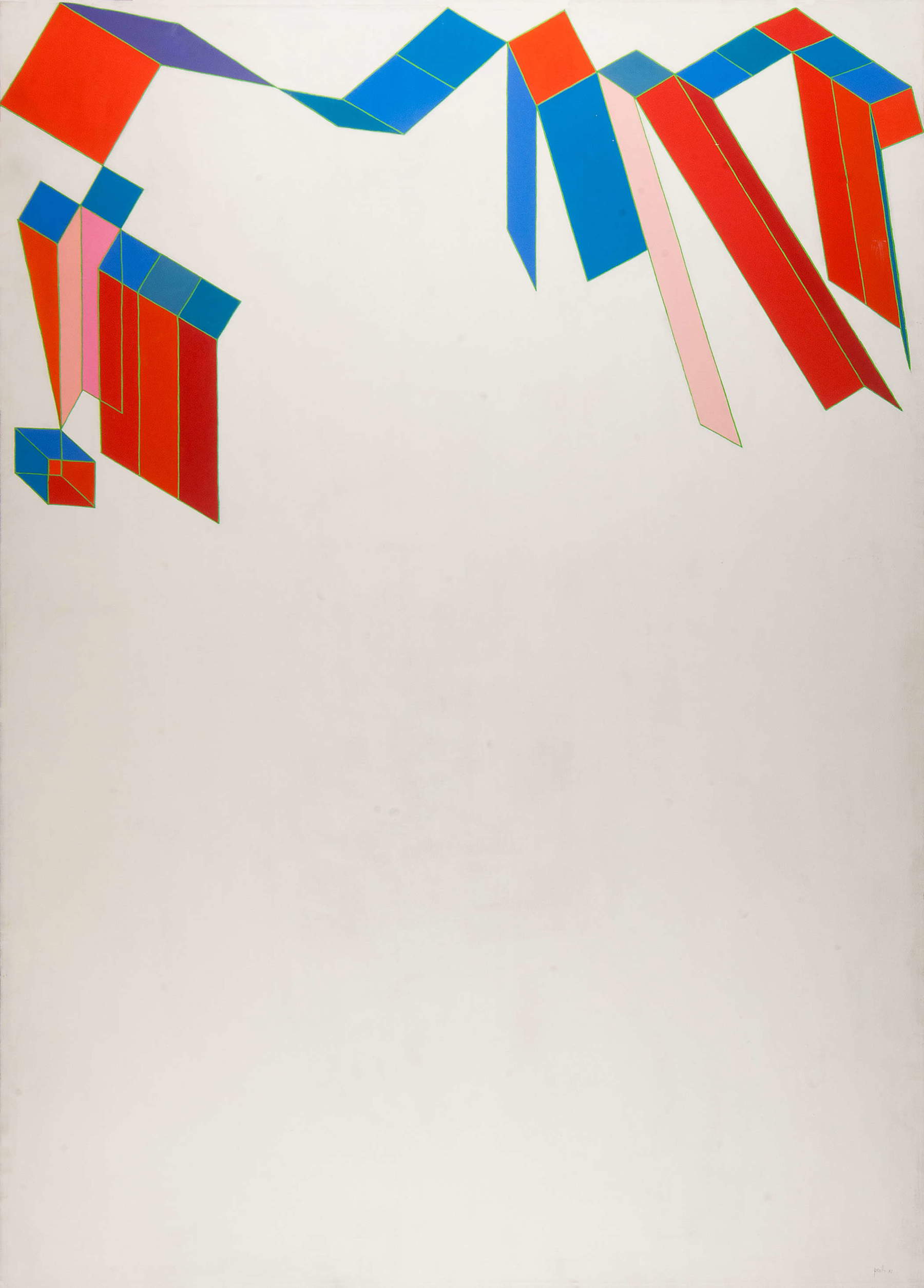

The works belonging to this cycle, present in the exhibition, are configured as plots of minimal passages, sequences that multiply without ever arriving at a conclusive synthesis. The sign abandons any descriptive function to become motion, a mental direction, an impulse that directs the gaze without ever guiding it toward a point of arrival. Forms expand and contract, distance and thin, deliberately avoiding any spatial stabilization. Volume is only suggested and immediately restrained, kept in a condition of controlled precariousness that prevents its full definition.

Within this unstable system, color takes on a foundational role. It does not merely support or fill the form, but incorporates it until it coincides with it. The color does not proceed through traditional tonal modulations, but is articulated in micro-differences and chromatic tensions that regulate the work’s internal progression. It is through these micro-differences that the visual rhythm is constructed, a scansion that does not follow a narrative order but develops as an autonomous perceptual experience.

With the passage of time, this research knows further developments. In the 1980s, the image seems to ideally extend beyond the physical boundaries of the canvas, through movements that are not visible and trajectories that are only perceived. The work opens to a mental space that continues beyond its perimeter, suggesting a potentially infinite dimension. In the 1990s, however, color asserts itself more decisively as a dominant element, becoming an autonomous and intense matter, capable of further dissolving the formal framework and minimizing all structural references.

In the later works, the irrational geometry that had characterized the earlier phases gradually gives way to a vibrant pictorial surface, built through minimal, almost imperceptible deviations. Depth is compressed into a unified field, similar to a concave surface that absorbs the third dimension and returns it as internal tension. The color creeps into the interstices, occupies the spaces left free by the sign, expands where the line recedes, until it itself becomes line and space.

As Achille Perilli writes in his 1982 manifesto L’irrazionale geometrico (The Geometric Irrational ), it is the internal tension of form that determines its progressive dissolution. The works in the exhibition clearly return this continuous shift from the perceptual to the mental plane, offering the gaze an experience that refuses hierarchies, privileged points of view and certain orientations. The resulting visual field is a space of controlled bewilderment, in which the loss of references is not a lack, but a necessary condition of seeing.

|

| Achille Perilli, the labyrinth of form on display in Naples at Alfonso Artiaco's |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.