A fragile and forgotten art, suspended between sculpture and science, comes back to life after centuries of silence. From December 16, 2025 to April 12, 2026, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence presents the exhibition Wax Once. Sculptures from the Medici Collections, an itinerary that rediscovers the extraordinary tradition of Florentine waxmaking between the 16th and 17th centuries. Curated by Valentina Conticelli and Andrea Daninos, the exhibition inaugurates the new exhibition spaces on the ground floor of the Gallery and represents the first review ever devoted to this theme in the city that was its main center of production.

Right from its title, Wax Once declares its intention: to revive a lost artistic field, which for centuries intertwined art, religion and science, but which time has almost completely erased due to the perishability of the material. Wax, a living and fragile, ductile and organic material, is in fact the medium that more than any other has been able to reproduce human flesh and its transformations. Through some ninety works, including sculptures, reliefs, paintings, cameos and works in hard stone, the exhibition recounts the fortunes and rediscovery of a language that once fascinated princes, scientists and artists.

Evidence of the artistic use of wax has ancient origins. As early as the first century CE, Pliny the Elder in his Natural History describes the custom of modeling images in wax, a tradition that in turn had its roots in Etruscan and Roman customs related to ancestor worship. From death masks, created to preserve the likenesses of the deceased, there was a gradual shift to true physiognomic portraits, simulacra that perpetuated the memory of familiar faces. The art of wax remained alive over time, surviving in popular and religious practices-from ex votos to devotional simulacra-until it experienced a moment of extraordinary splendor in Medici Florence between the 15th and 17th centuries.

In a context marked by scientific curiosity and attention to the body, wax became a material of choice for artists and scholars. Soft and neutral, moldable with exceptional precision and capable of accommodating color, it made it possible to depict life itself, restoring the appearance of skin and textiles with unprecedented verisimilitude. Renaissance and Baroque sculptors exploited its potential to create polychrome works of intense expressiveness, which combined naturalistic observation with technical virtuosity.

With the Baroque, an era dominated by reflection on transience and time, wax found a new and powerful symbolic dimension. Its organic origin - linked to the work of bees and thus to nature - made it the preferred material for representing the living body and its corruption, central themes in seventeenth-century figurative culture. Wax Once reconstructs this season through an itinerary that alternates between sculpture and painting, sacred and profane, wonder and meditation on death.

The curators’ goal is to recontextualize an art that is now almost forgotten, bringing it back to the time of its heyday, when waxwork was considered a prized genre, sought not only for shrines but also for princely collections. Aristocrats and patrons, fascinated by the realism of these sculptures, commissioned them to enrich their private galleries, alongside works in marble or bronze.

Many of these creations, once kept in the Uffizi or Palazzo Pitti themselves, were alienated at the end of the 18th century, when neoclassical taste and changing artistic sensibilities relegated wax to the status of a craft curiosity. Now, after centuries, some of those works are returning to Florence and being exhibited for the first time in their original location.

Prominent among the masterpieces on display are theSoul Screaming in Hell, attributed to Giulio de’ Grazia, an example of extraordinary dramatic tension and expressive rendering, and the plaster funeral mask of Lorenzo the Magnificent, modeled by sculptor Orsino Benintendi, a rare testimony to the tradition of post mortem effigies. These works dialogue with a selection of works from other Italian and international museums, in an interweaving that restores the breadth of an artistic phenomenon at once aesthetic, religious and anthropological.

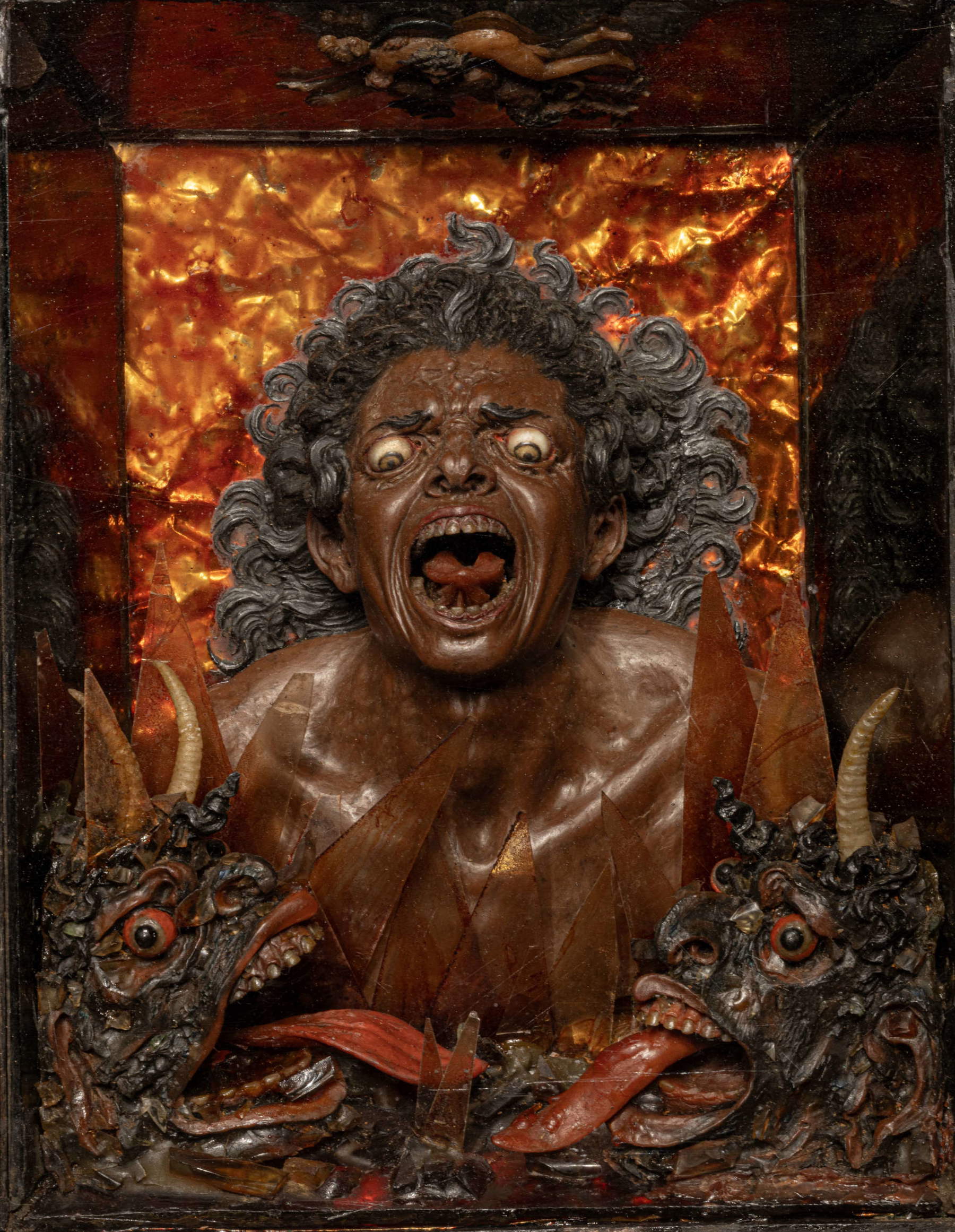

An entire section of the exhibition is devoted to Gaetano Giulio Zumbo, considered the greatest interpreter of Baroque ceroplastic and a key figure in the history of late 17th-century Florentine sculpture. A monographic room is reserved for him, in which the Galleries’ recent acquisition stands out: The Corruption of Bodies, a work emblematic of his style and poetics. Zumbo’s small masterpiece manifests his interest in the theme of decomposition and transformation of matter, in which wax becomes a metaphor for the fragility of life and the transition from body to dust.

The exhibition thus offers not only a review of works, but also a reflection on the identity of sculpture and its relationship with sensible reality. In the Renaissance and Baroque workshop, wax was often used as an intermediate step in the creation of models for bronze or marble, but its autonomous use as an expressive material revealed a deeper interest: that of reproducing the body in its imperfection, in its changing truth. Ceroplastic art, which would also find application in anatomical and scientific museums, was thus born as a form of artistic representation, capable of combining religious sensibility, naturalistic research and the emotion of the real.

|

| At the Uffizi the exhibition "Wax Once": the lost art of wax sculpture |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.