The contracts of 14 super-directors of museums and archaeological sites with special autonomy will soon expire. Among others, in September it will be the turn of Paolo Giulierini, head of the MANN, National Archaeological Museum of Naples; in October, James Bradburne, for the Brera Picture Gallery; in November it will be the turn of Eike Schmidt, for the Uffizi Galleries; and Sylvain Bellenger, for the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte. All eyes seem to be on the new public selections (will the international opening remain?). In addition to high-profile personalities (regardless of nationality), the other guarantee should be that the procedures for appointing directors, and then managing cultural institutions, will be safe from partisan attentions and corporate and academic entanglements.

But to evaluate the Formula 1 driver regardless of the car would be short-sighted. Almost ten years after its introduction, it is, therefore, perhaps time to take stock of the Franceschini-branded reform, of “epochal value,” ICOM Italia defined it from the start in that same 2014. The reform (the Ministry’s fifth reorganization), as is well known, granted some museums of major national interest, until then offices of the superintendencies, lacking a director, a form of special autonomy, endowing them with their own budget, statute and organization. And a director. On the positive/negative aspects or those to be perfected we will hear directly from the protagonists, the directors, because if the work is always the result of teamwork and even if the management model should have mitigated it, in practice it often inevitably ended up in a personalization of governance.

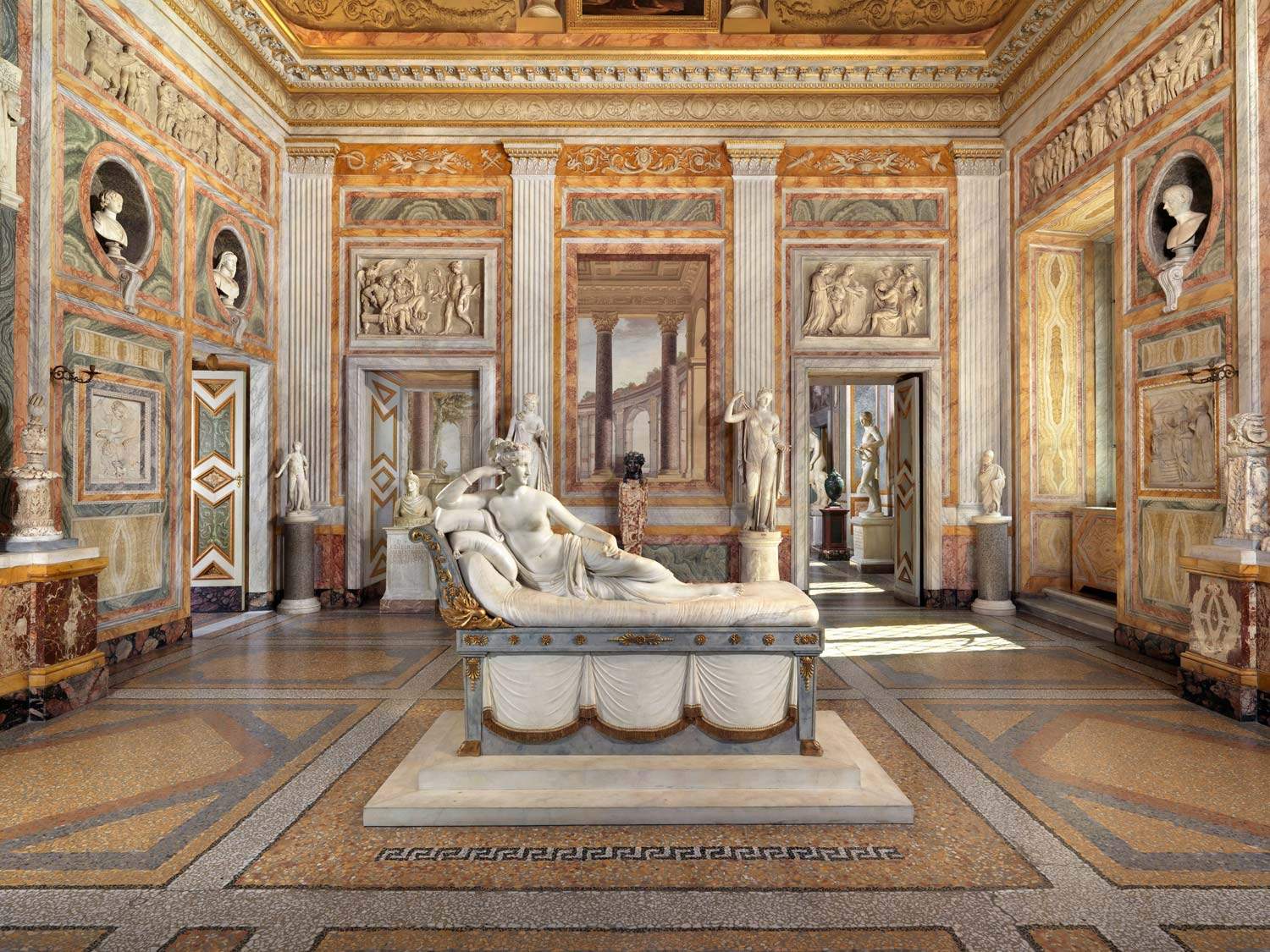

Five appointments, in which we will compare two institutions. Ten in all, then, among the twenty that have a longer course, established at the start of the reform in 2014: Borghese Gallery in Rome and Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence; Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence and Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice; Museum and Royal Woods of Capodimonte and Brera Picture Gallery; MANN, National Archaeological Museum of Naples and Paestum Archaeological Park; and National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria and GNAM, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome.

In particular, the only archaeological park originally envisioned, that of Paestum, will allow us to see how the reform was “adjusted” in the running on the protection front: at first clearly separated, remaining under the territorial superintendence, was then “resolved” by putting back under the park director also the protection of the assets and territory falling within the latter (while for museums it remains the responsibility of the superintendencies).

A “synoptic” comparison to understand to what extent the director-committee organization functions at the management level, not theoretically, but precisely in practice, since especially the scientific committees seem too often not to be involved in the director’s decisions; to check the scientific quality of the cultural offer and the way it is fulfilled, the practices of preservation, fruition and enhancement; citizen retention and territorial involvement activities (the latter especially for archaeological parks); all activities that, according to the mission of the museum, as also indicated by the new ICOM definition, should attest to its “success” more than the receipts issued, which seem, instead, to be the only objective parameter for awarding medals. And, again, autonomy, but to what extent? to what extent are these museums able to provide for enhancement and preservation by their own means? Then there is the problem of the shortage of staff with adequate and specific training that does not spare even these “happy islands,” since its allocation remains with the central administration.

An “episodic” investigation for an overview, far from claiming to offer systematic data. This one would need self-assessment, a very important tool for awareness of one’s means and needs, indispensable to guide future actions for continuous optimization. As is already the case with the national questionnaire of verification of the possession of minimum standards and uniform levels of quality, accomplished by the Museums Directorate itself and the basis of the process of accreditation of museums to the National Museum System. Or (but one would not exclude the other) evaluation through a third, independent body (Istat, University, CNR, for example).

So, we will try to understand whether and how the quality of operational strategies deployed by individual institutions are systematically evaluated. Since the metric, we said, cannot be only the quantity of visitors and receipts. Even if this seems to be the ball not only of the press, from “Sole24ore” to “Fatto Quotidiano,” but of the directors themselves, such as Schmidt, who in recent days, referring to the 2019 attendance record, announced triumphalistically that “we are very optimistic that this year we will be able to break this record,” and of Sangiuliano himself, who is planning to introduce a ticket for the Pantheon in Rome. Pulling himself out of the chorus is Valentino Nizzo, director of the Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia, who on his Facebook page, regarding the “way in which in journalism the action of museums is evaluated,” commented a few days ago, “if these are the parameters I don’t see the difference between the direction of a museum and that of a cinema or a supermarket.” In short, to change “only” the drivers at the helm of Ferrari would be for Minister Sangiuliano to put himself in a reductive position in the face of the complexity of the issue.

In this introductory article, meanwhile, let us frame the issue, with references to the (little-known) Sicilian precedent, where museums have been granted the status of “institute” since a distant law of 1980 (l.r. 116/80, art. 6), later supplemented by another specific regulation for museums (l.r. 17/1991). A close “model,” yet outclassed by the preferred reference to the French and English experience as examples of “limited autonomy.” Where the limitation, given by the “involvement of the authority in the decision-making process, through powers of control and supervision” (M.C. Pangallozzi, in "Aedon," 1, 2019), is the same as for Italian national museums (and Sicilian precedents, moreover not mentioned by Pangallozzi, as by others). But unlike museums beyond the Alps such as the Louvre or the Musée d’Orsay, for those of ours, they are not institutions with legal personality, they are not instrumental or auxiliary entities vis-à-vis the state (or an autonomous region, as in the Sicilian case, where only one of the 14 autonomous archaeological parks qualifies as an “entity”), however aimed at pursuing purposes of a public and nonprofit nature. Although no longer mere articulations of the superintendencies, they are still offices of the relevant ministry: through the Directorate General for Museums, which exercises powers of direction, guidance, coordination and control over most, and the Directorate General on which only some functionally depend. Evidently in order to shelter autonomy from interpretation in a personal and self-referential sense, as was later in fact confirmed by the “agitations” in the scientific committees that were not convened or the confrontations in the Higher Council of Cultural Heritage.

Rewinding the tape with us and taking a snapshot of the current situation is Massimo Osanna, head of that same Directorate General for Museums created in 2014 with the Dpcm that introduced for some institutes the new legal status that marked a clear line of demarcation with a past marked by the subjective “irrelevance” of the museum. “As is well known,” he explains, “that Dpcm August 29, 2014, No. 171, in addition to providing for the Regional Museum Poles (current Regional Museum Directorates, ed.) gave special autonomy to twenty institutes, identified among archaeological areas, museums and monumental complexes of significant national interest.” The medal of “big” was then awarded to the Borghese Gallery, Uffizi, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, Museum and Royal Woods of Capodimonte, Brera Picture Gallery, Reggia di Caserta, Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, Gallerie Estensi, Gallerie nazionali d’ancient art, Bargello Museums, National Archaeological Museum of Naples, at the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria and that of Taranto, at the Ducal Palace of Mantua, Royal Palace of Genoa, Royal Museums of Turin, National Gallery of the Marches and the National Gallery of Umbria. Only one archaeological park, that of Paestum and Velia.

“The number of autonomous institutes,” Osanna continues, “has been progressively expanded to forty in 2019. To these, four additional new ones were added in 2021. These are the National Museum of Digital Art, Archaeological Park of Cerveteri and Tarquinia, Archaeological Park of Sepino, and the Pinacoteca of Siena.” Consequently, “this change has raised the number of regional museum directorates,whose function of director is carried out by that of the autonomous museum located in the same region: thus, from the four in 2020 (Friuli Venezia Giulia, Liguria, Marche and Umbria) has risen to five in 2021, with the addition of Molise.”

Being autonomous in administrative, organizational, managerial, financial and accounting terms means, in a word, organizing one’s activities autonomously. The autonomy in identifying one’s cultural, and ultimately also civic, mission, which each of these “special” museums declines differently, is clearly inferred from each individual statute.

There is, however, big and big: there is a difference in the gradualness of this same autonomy, and therefore of the responsibilities of the directors, that differentiates the museums of general executive level, eleven in all, including the Uffizi, Brera, Capodimonte, Colosseum, Pompeii and Borghese Gallery, whose directors are chosen directly by the minister, those we said depend functionally on the General Directorate, from those of non-general executive level, thirty-three in all, such as the Pilotta Monumental Complex, the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, the National Archaeological Museum in Reggio Calabria and the Estensi Galleries, with directors chosen by the Director General of Museums and, unlike the former, subject to the powers of direction, coordination and control of the Directorate itself. For example, to determine the amount of tickets or opening hours. The Uffizi, for instance, has just been able to raise the cost of the ticket from 20 to 25 euros, without this step, in full autonomy. The economic treatment reserved for directors belonging to the two bands is also different.

But what does managerial and financial autonomy consist of in practice? Autonomous institutes keep the receipts from the management activity of the conferred assets (entrance tickets, fees from concessions of space and assets, rights of use, reproduction, merchandising, services provided for a fee, editorial productions, etc.), receive a base from the Ministry for personnel and structural interventions, and have their own budget (however subject to ministerial approval).

The advantages had highlighted them (to this writer, in “La Sicilia,” March 19, 2021) by Antonio Lampis, now head of the Italian Culture Department of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano, who preceded Osanna at the Museums Directorate in years of historic changes on the very front of the new governance of cultural institutions. This arrangement “allows,” he told us, “to speed up the procedures related to accounting, expenditures, concessions or even entry of funds from private individuals. The treasury and cash service is entrusted by each institution, through a public procedure, to a bank. Before, they received, with lengthy procedures, allocations from ministerial offices and everything they earned ended up in a single cauldron.”

Autonomous museums then contribute 20 percent of their ticketing to a Financial Rebalancing Fund among state institutes and places of culture, an equalizing measure. “The financial resources for rebalancing among the institutes are allocated,” Lampis further explained, “by the General Directorate for Museums, providing for increases for documented serious needs for mandatory expenditures and reductions for low spending capacity, or for huge revenues from new external resources or increases in ticketing.” In 2020, for example, it told us that lost revenue caused by Covid-19 had been taken into account. If the original rationale was not only “redistribution” but also incentives from a corporate perspective, we will try to figure out with the directors how the “rewards” come and for whom they are reserved.

The administrative organization is what makes the difference from “ordinary” management institutions. The director, a monocratic body, is assisted by three collegial bodies that configure an arrangement quite similar to that of an entity with legal personality: Scientific Committee, Board of Directors and Board of Auditors. They are responsible for ensuring that the museum’s mission is carried out.

The BoD is the top body, those in which most of the choices are actually made: it dictates the administrative lines and, among other things, approves the budget and museum activities; it is chaired by the director, and is composed of four other distinguished members appointed by the Minister of Culture, in agreement with the Minister of Education and the Minister of Economy. The Scientific Committee performs an advisory function to the director in deciding the scientific lines of the museum, but also verifies the scientific quality of cultural offerings and conservation practices, and approves lending policies and exhibition planning. It is composed of 4 members appointed by the Minister, Higher Council of Cultural Heritage, Region and Municipality, identified from tenured university professors or experts with proven scientific qualifications. The Board of Auditors, composed of an official of the Ministry of Finance and two alternate members, registered with the Register of Auditors, is responsible for monitoring the museum’s use of funds. Management inspired by the corporate model, as often observed, but also by the university model, if you prefer. With the aim of overcoming standardizing bureaucratic ties that cripple the speed of decision-making in a sector that by its nature cannot be regulated by mechanisms designed for the market economy.

The pyramidal organizational design of the supermuseum is complemented at the base by an articulation into functional areas: collections care and management, study, teaching and research; marketing, fundraising, services and public relations, public relations; administration, finance and human resources management; and of facilities, exhibition design and security.

In Sicily, on the other hand, where this corporatist model was first applied to cultural institutes (apart from the case of the Riso, Museum of Contemporary Art in Palermo, with financial autonomy that has remained on paper since 2002, these are exclusively archaeological parks), there is a worrying, primarily for the purposes of protection, mixture of administrative and political functions, with mayors on the technical-scientific committees.

One man at the top cannot work miracles. Changing or rotating directors of autonomous museums will always have to reckon with the serious problem of staff shortages. Sangiuliano, after the Uffizi case, said it is a “very serious issue that I will face with determination.” The directors themselves have raised it in the press before, from Eike Schmidt to Carmelo Malacrino for the National Museum of Reggio Calabria.

Human resources, in fact, are not included in the organizational autonomy of the special museum and remain the responsibility of the Ministry. The individual museum cannot, in fact, recruit professional figures according to its own technical-operational needs, the Ministry being the one to do so, providing for all charges related to economic treatment. Precisely in Sicily, first the Crocetta government and then a bill during the last legislature (we dealt with it in these columns), provided that in the case of the appointment of a director from outside the administration, his or her economic treatment would be borne by the park’s budget. In other words, a director called upon to promote “cultural activities” with the sting of the need to secure a salary! Fortunately, proposals that remained a dead letter, but even just trying to do so makes it clear where this was intended to go and, above all, that autonomy is right to find a limit in an area that must be kept safe from the logic of profit.

The author of this article: Silvia Mazza

Storica dell’arte e giornalista, scrive su “Il Giornale dell’Arte”, “Il Giornale dell’Architettura” e “The Art Newspaper”. Le sue inchieste sono state citate dal “Corriere della Sera” e dal compianto Folco Quilici nel suo ultimo libro Tutt'attorno la Sicilia: Un'avventura di mare (Utet, Torino 2017). Come opinionista specializzata interviene spesso sulla stampa siciliana (“Gazzetta del Sud”, “Il Giornale di Sicilia”, “La Sicilia”, etc.). Dal 2006 al 2012 è stata corrispondente per il quotidiano “America Oggi” (New Jersey), titolare della rubrica di “Arte e Cultura” del magazine domenicale “Oggi 7”. Con un diploma di Specializzazione in Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna, ha una formazione specifica nel campo della conservazione del patrimonio culturale (Carta del Rischio).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.