June 22, 2020: in Florence, a group of citizens takes to Piazza della Signoria to protest against the City Council, which, more than a month after reopening operations after the end of the confinement to contain the Covid-19 contagion, still keeps as many as eight out of thirteen civic libraries closed, while those that are open operate with reduced hours and services. Two weeks later, the City Council finally announced the reopening of all libraries: a victory for citizens, not least because all libraries in Florence have returned to guarantee their activities with normal hours and almost full capacity (it is possible to do shelf searches, access study and reading rooms, make use of the lending service, internet stations, and digital devices), while still keeping in mind the anti-Covid protocols, which require reservations to access libraries, whatever the reason. In addition, each user has a carnet of up to three reservations per week and has an assigned location. In addition, there is the fact that everywhere in Italy, there is a “quarantine” period for borrowed books, which cannot be put into circulation until one week after they have been returned. We are not yet, in short, at full normalcy, but at least it can be said that Florentine libraries are now back in operation. But for how many cities in Italy can the same be said?

Starting with the national libraries, the situation is far from normal in almost all the major hubs. The two large central libraries, the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Rome and the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, still operate with reduced opening hours: in Florence, access is available, and only by reservation, from Monday to Friday and from 8:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. (moreover, on the BNCF website the new hours are written in red above the old hours, which still appear on the page with information about opening to the public, creating confusion), while in the capital there are only four hours available, from 9:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. Same hours as in Rome also at the Braidense in Milan, which, however, also opens on Saturdays. The Statale in Cremona, on the other hand, opens only three days a week (Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays, from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.), and only by appointment, and each of the three days is dedicated to a different service (Mondays only national interlibrary loan and rare material consultation, Wednesdays local loan and provincial library network, Thursdays rare material consultation). Of course, access is allowed everywhere by reservation only, and the material to be requested for loan or consultation must also be reserved in advance. Then there are room quotas. At the Casanatense, for example, a maximum of six users per room enter. At the Angelica, four, and only for properly documented study and research purposes. Access is also prevented to users who bring their own books from home (a situation, this, common to many other libraries).

Several services remain suspended in many libraries: catalogs cannot be consulted on site at the Palatina of Parma, the Library of Santa Scolastica, the Universitaria of Padua, and the Casanatense. Photocopy service suspended at Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, at Palatina, at Nazionale di Cosenza, at Biblioteca di Santa Scolastica, at Universitaria di Genova, at Universitaria di Padova. Interlibrary loan suspended at the National Library of Bari, the Estense, the University of Padua. Reading rooms are still closed at the Isontina in Gorizia and at the Alessandrina (which opens only the General Reading Room, and which, moreover, has suspended the reference service for rare volumes). And then consider that many libraries opened their doors only at the end of June, or at any rate several weeks after the end of the so-called lockdown.

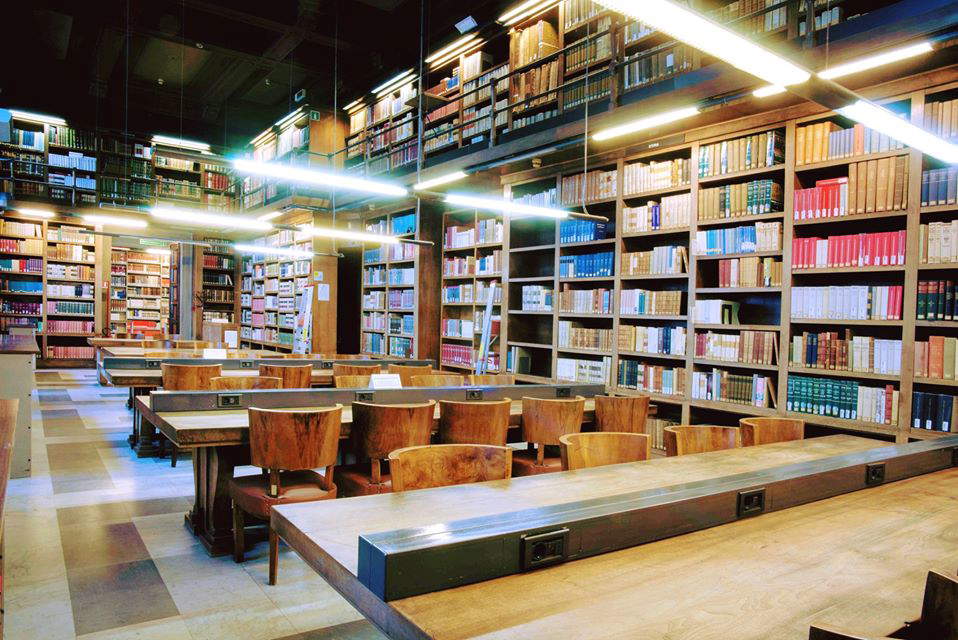

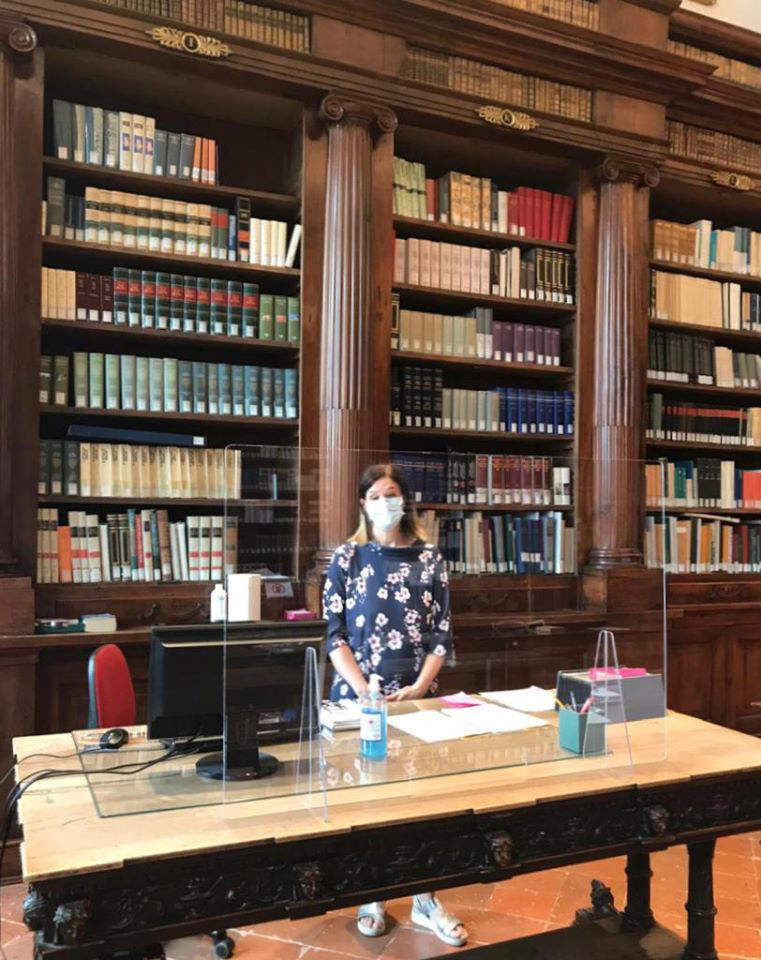

|

| A room at the National Central Library in Florence |

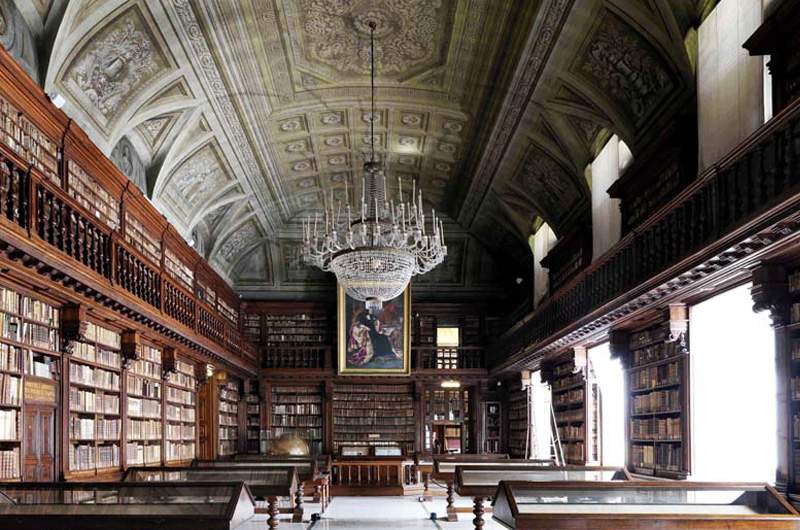

|

| The National Central Library of Rome |

|

| The Braidense National Library (Milan) |

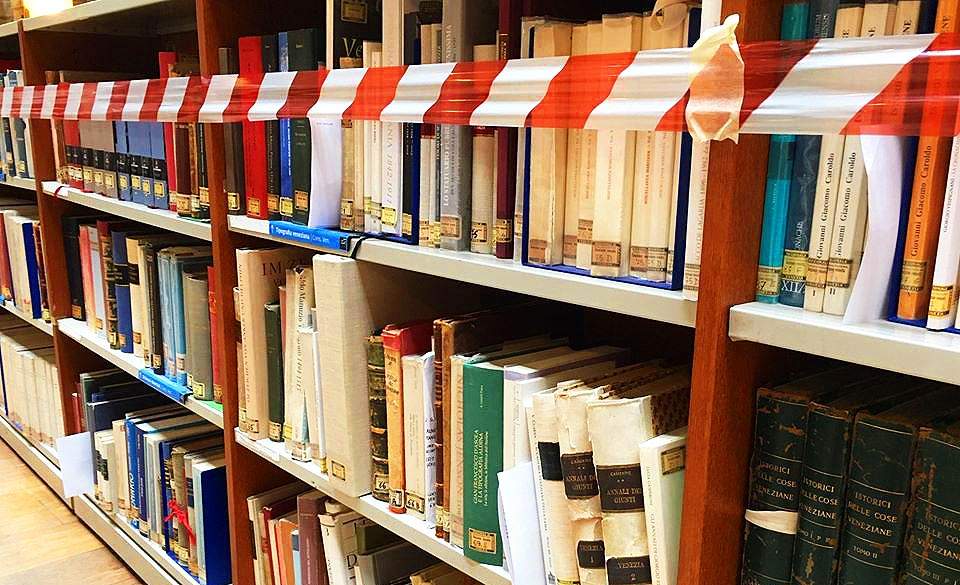

|

| Ban on browsing books on the shelf at the Marciana National Library in Venice |

To understand what discomfort this situation entails (and it is important to emphasize that each library decides for itself, since even at the national level there is no coordination, exactly as happens with state museums, which since May 18, the date of the end of confinement, have begun to reopen in a spotty manner, without pre-established calendars, and with different hours everywhere: the same thing happens for libraries), it is enough to scroll through social networks in search of user comments. Weighing down, above all, are the strict quotas for access to the reading rooms (due to the small numbers and the fact that seats are guaranteed only by reservation, there is indeed a serious risk of not finding a place): and studying in the library, for many who do not have quiet environments where they can devote themselves to their work or research activities, is not an option. Then there are the paradoxes of the reservation system: if there happen to be vacancies, those without reservations are still denied access. There are also severe limitations for scholars: “reopening libraries for lending,” writes Matthew on the Facebook group “Libraries and Librarians” (which gathers more than ten thousand members and collects several posts and comments from library users every day), “actually prevents research (yes, in large libraries there are ancient collections, manuscripts, parchments ... all material you can only view on site) and the consultation of books (and there are so many) that are not allowed to be borrowed for obvious reasons of rarity as they are often local editions or very large volumes.”

“At a time when so much of the space is open more or less close to normal,” Leonardo Bison, an activist with Mi Riconosci? I am a cultural heritage professional, an association among the most active in highlighting the situation of libraries, “the chaos over libraries has strong consequences for library workers as well, because many are having contract consequences. The consequences, however, are very strong for the users, which is not only a user base of researchers or people who assiduously frequent libraries and need them for work (and this is obviously a huge criticality for us cultural heritage professionals and not only), but there is also a whole user base of people who have no spaces in which to study, no spaces to gather, so libraries are and should be social spaces. And it is grotesque and worrying that in a summer like this, with the situation that the country is experiencing, we find ourselves deprived and deprived of social, cultural and aggregation spaces when in fact then the spaces related to consumption are almost totally available. We would then like to point out that the lack of coordination on the part of the General Directorate of Libraries of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism is worrying, because so many of the difficulties come from the fact that there are guidelines that are not in line with what is happening around the country and also in situations where it is much more difficult than in a library to maintain spacing.”

The Facebook page of Do You Recognize Me? is an interesting source for understanding what inconveniences are caused to users by such a precarious situation. There are those who, for example, prefer to go to the bar to study: the establishments are still required to enforce the rules on physical spacing, and if the managers are obedient to the rules, the risk of contagion does not exist (consider, for example, that in libraries there is an obligation to wear a mask at all times, even when it is possible to respect the spacing, which is still mandatory). This is the case of Elena, a Sienese architect working in Bologna, who has chosen the bar as her improvised study room instead of the library: “In the library,” she says, “I would have to keep my mask on at all times (even at my table, two meters away from the others and obviously without speaking, because you go to the study room to work in silence, not to make a living room!), and book myself online on their website or by calling every other day (because you cannot book for example the whole week, eh no, but only for the same day and the next day). I console myself with the thought that at least I help (in my small way) my trusted bartenders to work. But I certainly cannot afford the bar every day, both for cost and concentration issues because people (rightly!) go to the bar to chat and relax, and I can only do work there that requires low to medium concentration.” A Roman user, Giada, wrote a couple of weeks ago, “in Rome the libraries are slowly reopening, from next week some outdoor study rooms will be usable. The library at my university (Roma Tre) only grants loans with email reservation, with waiting times of about 10-14 days, in August it will close for 3 weeks. No word on how it will go in September. It is not possible to do research in this situation.”

|

| A reading room at the Marciana National Library in Venice |

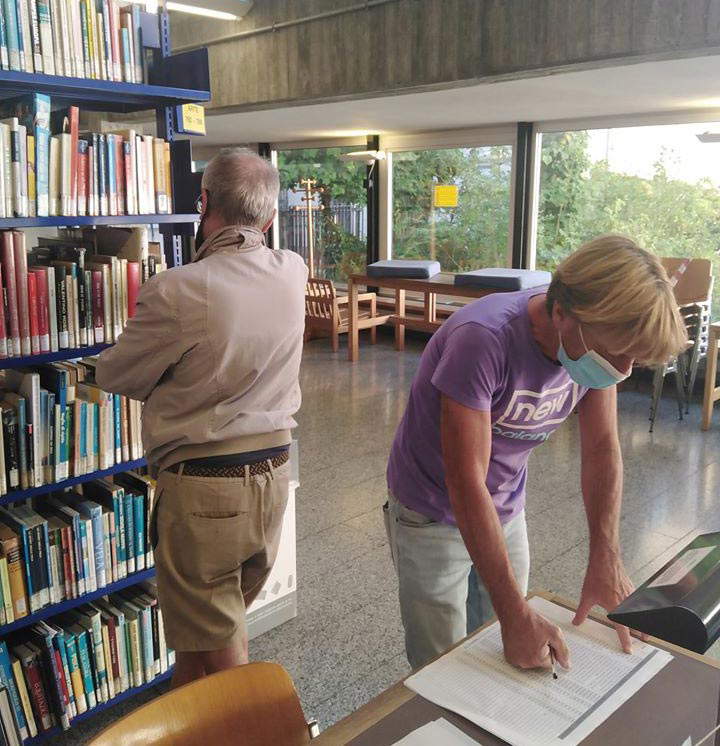

|

| Users at the Berio Library in Genoa |

As for local libraries, the situation is not so different from that of national libraries. Here, too, there are poles that have reopened and are trying to guarantee all services to users, but there are also situations where closures and reductions in activities remain. One can start with one of the cities symbolic of the Covid-19 epidemic, Bergamo, where in fact in many provincial libraries one can go only to pick up loan books reserved in advance (this is still the case in Alzano Lombardo, Capriate San Gervasio, Dalmine, Nembro, Pedrengo, Sarnico, Stezzano, Treviglio and several other centers in the provicnia). “In the vast majority of cases,” Alice Barcella, a librarian who works for Abibook, a cooperative that manages several provincial libraries, confirms to us, “users cannot enter, or they can only do so for the loan service. The books are quarantined, which in theory should be seven days, but most libraries do it for ten days (there is no official deadline, but there are just recommendations), and that is also an inconvenience. Also because sometimes books that come from other libraries are quarantined: that is, I get a book from a user, I quarantine it ten days because it has returned, after which I send it to another library because it belongs to that library, and that library in turn quarantines it for another ten days, with the result that some users have to wait three weeks before they get a book. And it’s not just about the pleasure of reading: so many books are needed to prepare for exams and competitions, so this is a very important inconvenience.” As far as activities are concerned, in the province of Bergamo, Alice Barcella points out, “most libraries remain closed and it is forbidden to consult the books, that is, the books are either not consulted, or they have to be borrowed if they come into contact with the volume. In some libraries, however, fortunately, consultation is guaranteed, provided, of course, that the user sanitizes his or her hands first. Other activities have also been suspended, for example, internet stations, magazine consultation, photocopy service, and some libraries continue to close or open reading rooms at very reduced hours.”

The precariousness of the situation also affects workers, especially those who work for outside companies to which local governments contract library services: they are the first to suffer the heaviest consequences of the situation. In the meantime, Alice Barcella lets us know, “I sense that the clash between those who feel more about their work and do it with passion, and those who are not so attached, has escalated.” Not least because, at such a juncture, it is the users who are the first to complain if library workers do not offer their best efforts. But it’s not just a matter of attachment to work, because there are those who risk having their jobs cut back. So Marta Ghirardello, a librarian who works in the Rovigo provincial system, tells us. “At the moment,” she lets us know, “I manage three separate municipal libraries, working for three different cooperatives. Good or bad, we are all back in service, but the situation was already problematic in the pre-Covid period, in the sense that most of the workers are employees of cooperatives, usually on fixed-term contracts, disbursed on the basis of contracts from municipalities. The problem is that there are few stable situations and little continuity. For example, the cooperative I work for just lost a contract, so we are waiting to know who we will work with and if we will work, and under what conditions.” And then there is the problem of compliance with anti-Covid regulations: larger libraries have no major problems complying, but that is not the case for smaller provincial hubs. “Right now,” Marta Ghirardello continues, speaking of the Rovigo library system, “the libraries have all reopened, but we are still stuck on May 18, in the sense that services are provided only for loan and return. There is no possibility of study room and internet, for example, except in a few cities, where there are administrations that have taken the trouble to reopen some of the activities. In many cases there are not the financial possibilities to ensure the dictates of the ministry regarding sanitation, there are space problems to enforce spacing, and so on. It’s not that there is a lack of will: it’s mainly economic and logistical problems.”

Instead, she works in the province of Ancona, librarian Chiara Azzini, who with Finestre sull’Arte talks about what is happening in her area: “The majority of libraries in the province have reopened, but always with reduced hours, and in several cases people enter only by reservation, and without access to services such as shelf consultation or newspaper reading, for example. Some libraries are beginning to reopen their halls instead, but in most cases there is this system of only lending and reservation access, and no shelf consultation. And users have had to adapt, but they are still in trouble: just think of the students who are constantly prevented from accessing the reading rooms because of the bans still in place. The measures on books then force many students who are normally users of university libraries to turn to local libraries, which, however, cannot satisfy them because many texts, in smaller centers, are unfortunately not there.” Chiara is among the workers who are suffering on their skin the worst consequences of the virus on the Italian cultural system: “Before the coronavirus,” she explains, "I worked for three different cooperatives (so I had three employers), and with each one I had a contract: adding them up, I was able to work full time. Now I have lost half of my job, because we lost the contract on some libraries. The coronavirus, however, has only exacerbated a situation that existed before and for many years, we knew it would come to this: I am referring to the gap between guaranteed workers and employees of cooperatives who count for practically less than nothing. As far as my situation is concerned, a contract has been allowed to expire without there being a renewal, and in other cases there are cooperatives that have blown up and we don’t know if there will be a follow-up. Of course we know that the period is difficult for everyone, but it is also true that the coronavirus has taken a situation that was already very complicated for us before to the extreme."

|

| Anti-contagious Plexiglas station at the Angelo Mai Civic Library of Bergamo |

|

| Signs illustrating the new access arrangements at the Municipal Library of Corinaldo (Ancona, Italy) |

|

| A room at the Civic Library of Porto Tolle (Rovigo) |

|

| Outdoor activities for children at the Baratta Civic Library in Mantua |

How is the world of culture responding? Unfortunately, the feeling is that there is no real interest in libraries. At the moment, the minister of cultural heritage, Dario Franceschini, has not yet spoken out on this issue with ad hoc interventions. For now, the only intervention is a decree allocating 30 million euros for the extraordinary purchase of books by state and regional libraries, local authorities and cultural institutes. This is an important help, especially for small village libraries whose acquisitions have been at a standstill for years, but it is not enough, because from many quarters there are calls for the restoration of the full operation of libraries: this is not a luxury or a divertissement for dusty researchers, but a fundamental garrison for a country that wants to grow, both economically and culturally, that wants to try to smooth out social differences (think of those who use libraries because they cannot afford to buy books) and that wants to be competitive internationally. The grassroots therefore calls for changes at the practical and regulatory levels.

TheAIB-Italian Library Association, for example, noted that the most authoritative biomedical sources have concluded that potentially contaminated paper materials should be isolated for 72 hours, or three days (instead of at least seven as prescribed by the Central Institute for the Pathology of Archives and Books of the MiBACT for books returning from lending), and they are asking MiBACT and the Directorate General of Libraries to revise the recommendations by establishing three days as the quarantine time for books.

Most recently, the National University Council for Art History has written a letter to Minister of Cultural Heritage Franceschini, Minister of Universities Gaetano Manfredi, and MiBACT’s Directors General of Archives, Libraries, and Education (Anna Maria Buzzi, Paola Passarelli, and Mario Turetta, respectively) to call for the reopening of archives and libraries to full capacity. “The limited hours and the incomprehensible other impediments,” Fulvio Cervini, president of the Consulta, wrote in the missive, “seem to us to be affecting a sector, that of study in libraries, which is vital for the world of research and teaching, particularly the university world that the signatories of this letter represent. Doctorates, projects, and all kinds of scholarly publications, not only academic, but museum and conservation, have been at a standstill for months, and no authority has yet foreseen and communicated what the horizon is for the scholarly community to contend with. The fear is that this sector will be left behind because it is not directly connected to the structures of commerce and industrial production. It is, however, as Minister Franceschini has always maintained, one of the most crucial and characterizing areas of the nation’s life, that oil that is not only made up of entrance fees to museums, but must be integrated with a great background, academic and conservative, for which Italy has a leading place in the world.”

This summer, in conclusion, libraries seem to be open only formally. There is certainly no shortage of hubs where, on the other hand, a return to normalcy as close as possible to what has been given so far has been attempted: an exemplary case is that of the “Gino Baratta” Library in Mantua, where there are continuous hours six days a week, and where there are also two evening opening days, Tuesdays and Thursdays, until 10 pm:30, albeit with all the limitations that the situation entails, i.e., restricted entrance to the reading rooms, compulsory use of a mask, reservations for the use of the rooms, computer stations, and even for reading newspapers, although in the latter case reserving a place is not compulsory but strongly recommended. Moreover, the Mantua library, having outdoor spaces, also manages to initiate workshops and activities for children and readings and events for adults. But such cases are not so common. Everywhere there is still a strong sense of confusion and difficulty that a country like Italy can no longer afford: culture, society and the economy cannot do without libraries. And it is therefore urgent to improve the situation.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.