Until now, its viewing had been a privilege for few, as it was not available even in specialized film libraries. On the Web, an initial fragment of just two minutes circulated. We are talking about Lo scultore degli angeli (The Sculptor of Angels), a documentary dedicated to Giacomo Serpotta (Palermo, 1656 - 1732), the Palermo artist with an extraordinary ability to model in stucco even the most delicate and graceful figures, such as the angelic ones, with which he particularly enriched his fellow citizens’ oratories. The film, which had been all but lost to memory, had been revived after the rediscovery of a 16 mm copy by the director, also from Palermo, Sergio Gianfalla. The story in part has been told and now some details can be clarified: who knows why the reel lay abandoned, along with other unfiled ones, at theIstituto Sperimentale Zootecnico per la Sicilia. Gianfalla was there in 2008-09 for a collaboration with the institution, of course of an entirely different nature, and on that occasion he took with him the ’lost’ media, otherwise destined for the scrap heap. We can imagine all the amazement in projecting then in the laboratory the flickering images in Ferraniacolor and discovering as we go along the unexpected contents, in the atmosphere of yesteryear to which the narrative voice of Aldo Franchi, who is also director of the short film, and the original music by Giuseppe Rosati bring back. Astonishment that will be the same of those among the fans who can now benefit from the full publication of the video. Providential indeed was the digital reconversion of the tape, which has since crystallized and is no longer usable.

Of the original film produced by the Sperimental Film of brothers Alfonso and Agostino Sansone, a 35 mm with a total length of 10’30’’, it is possible to trace the date of its making in 1957 thanks to the censorship visa (Italia Taglia database). With this ’synopsis’ there the product was presented: “The documentary aims to illustrate, following the work of one of the greatest sculptors who worked in Sicily, Giacomo Serpotta, the artist’s works in the various oratories where he worked. In addition to his work as a sculptor, the documentary also illustrates his power to architecturally compose the framed figures of such illustrious works as Van Dyck and Caravaggio. Of the various works of this inimitable artist, a very valid testimony of the period and a stylistic balance rare to be found in Sicilian art results.”

|

| Photogram of Aldo Franchi’s The Sculptor of Angels, 1957. |

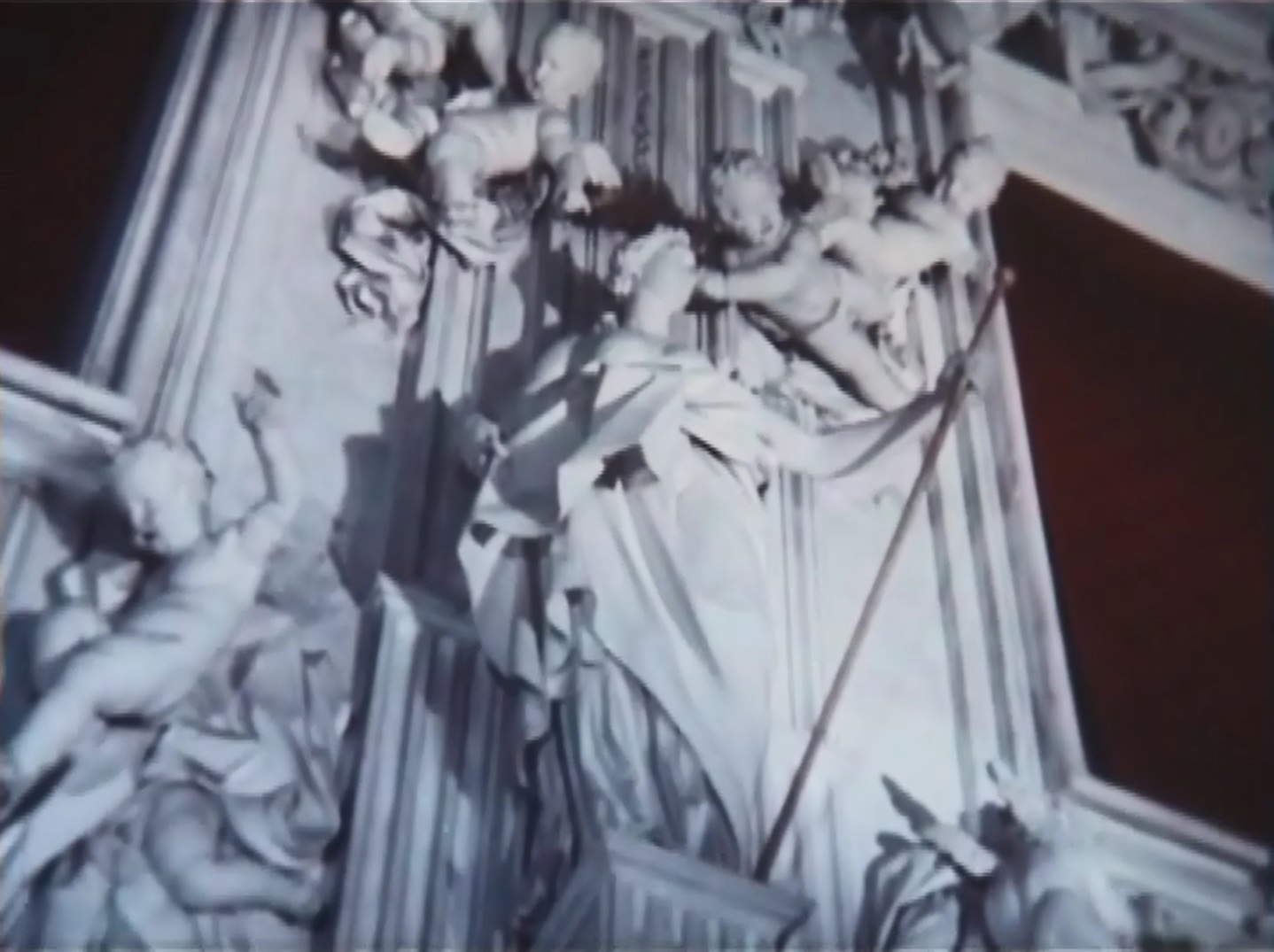

|

| Photogram of Aldo Franchi’s The Sculptor of Angels, 1957. |

|

| Photogram of Aldo Franchi’s The Sculptor of Angels, 1957. |

The 1957 date had not been so obvious until now. Gianfalla had at first thought of documentaries made mostly (but not exclusively) in the first half of the 1960s, to compete for the disbursement of a “quality award.” And indeed, ours, some recognition did: it turns out “8th Premio Sicilia” (S. Jesus, La Sicilia della memoria. Cento anni di cinema documentario nell’isola, Catania 1999, p. 128, where the entry in question appears under 1958, probably the year of the competition). This is evidently the Sicily Prize for documentaries of special interest to tourism, which was held as part of the International Film Review of Messina and Taormina (from which today’s Taormina Film Fest would be born).

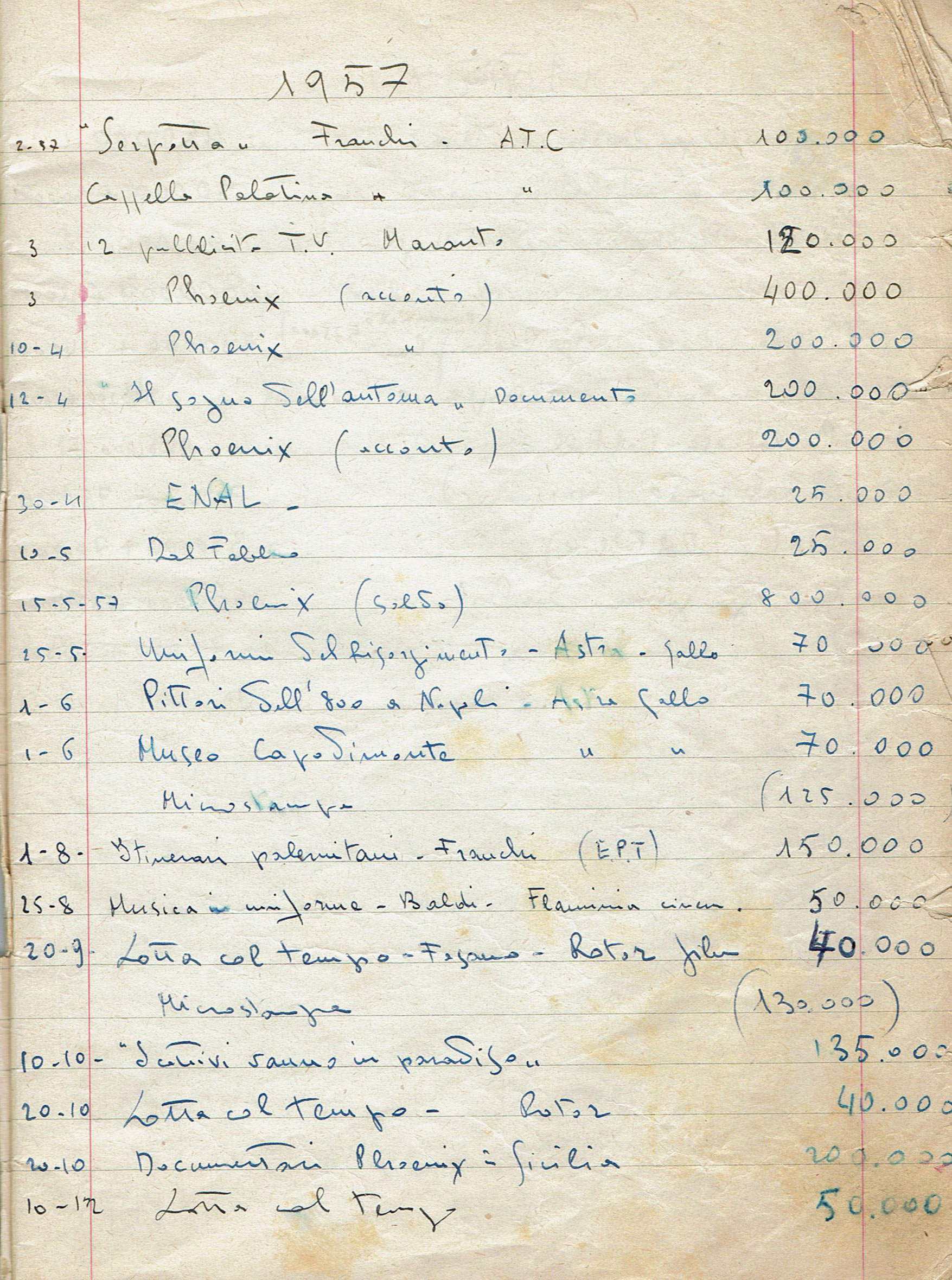

We can now also trace the period in which the filming took place. Sandro Aquari, son of Giuseppe, director of photography, dusted off for us the notes of his father, who jotted everything down. In February 1957 we recognize the record of the compensation (of one hundred thousand liras) received for that work: “2-57 ”Serpotta“ Franks - A.T.C 100,000.” Where ATC, stands for “Attrezzatura Tecnica Cinematografica,” a rental company that among its founders had not coincidentally the Sansones. And it was precisely “Serpotta” that the film was more colloquially called at the director’s home, in the still vivid recollection that his son Roberto Franchi tells us. On the other hand, the images of Palermitans in heavy clothing, reconcile with footage shot in winter (that of 1956-57). On the other hand, it arouses almost tenderness, in the opening frames, the pair of nuns wearing the typical headgear called cornetta, crossing a busy Via Maqueda.

|

| Accounting page by cinematographer Giuseppe Aquari, 1957 (courtesy of Sandro Aquari). |

In 1957 Serpotta’s genius had not yet achieved the notoriety he rightly but not yet sufficiently enjoys today. Singularly in the same year an article on his “plastic theater” was published by Giulio Carlo Argan, who a couple of years earlier had begun university teaching in Palermo, as Serpotta expert Pierfrancesco Palazzotto points out. So much so as to suggest suggestively, on the whole, a sort of revival or at least a renewed interest that was taking shape at that time for the artist. For the short film, however, one can imagine some involvement of Filippo Meli, rector of the Oratory of San Lorenzo to which the first part is dedicated and the only one mentioned among scholars of the famous sculptor and stucco artist.

|

| Oratory of San Lorenzo, Palermo. |

|

| Oratory of the Rosary in San Domenico, Palermo. |

|

| Oratory of the Rosary in Santa Cita, Palermo. |

|

| Caravaggio, Nativity (1600; oil on canvas, 268 x 197 cm; formerly in Palermo, Oratory of San Lorenzo, stolen in 1969) |

|

| Anton van Dyck, Madonna of the Rosary (1625-1627; oil on canvas, 397 x 278 cm; Palermo, Oratory of the Rosary in San Domenico) |

|

| Carlo Maratta, Madonna of the Ros ary (1695; oil on canvas; Palermo, Oratory of the Rosary in Santa Cita) |

The sculptor of angels leads the viewer in a few minutes (and a few hundred meters) from the Oratory of San Lorenzo to the Oratory of the Rosary in San Domenico. Where among putti, allegories and stucco “little theaters,” the altarpieces by Caravaggio and van Dyck, respectively, make a fine display and are certainly enhanced by the plastic apparatus. Left out of the narrative is what together with the previous ones can be considered among the author’s three best achievements, namely the Oratory of the Rosary in Santa Cita. The latter boasts inside a no less excellent canvas by Maratta and suggests that, for a matter of prestige and mutual competition, the confraternities that were based in these places turned in all three cases to painters who came (and worked) from outside: Rome for Caravaggio (1600) and Maratta (1695), Genoa for van Dyck (1625-27).

Aldo Franchi’s work, beyond all other merits including a poetics of narration that does not leave one insensitive, has the merit of documenting for the only time in a full-color audiovisual the Nativity by Merisi, whose fiftieth anniversary of its theft (October 1969) falls this 2019. It is seen for a few seconds, illustrated as “the last work of the famous painter.” So it was still believed at the time: all recent is the rediscovery of the Roman dating. If at least clarity has been gained on this, the case of its disappearance remains unsolved, the so-called file 799 as filed by the Carabinieri’s Cultural Heritage Protection Command. However, an investigation reopened by the Anti-Mafia Parliamentary Commission chaired by Rosy Bindi has at least been able to reconstruct its first steps, from the material theft by a gang of petty thieves, to the meddling and acquisition of the canvas by Cosa Nostra, to its sale and departure for Switzerland in 1970.

Who knows, maybe one day it will resurface, perhaps from the most unthinkable place and by a stroke of luck as happened with the film that still revives its memory.

The author will present these and other news at the scientific conference The Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. The event will be held Oct. 14 at 6:30 p.m. at the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo, as part of the Caravaggio#50 event , and will feature Francesca Curti, Giovanni Mendola and Maurizio Vitella.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.