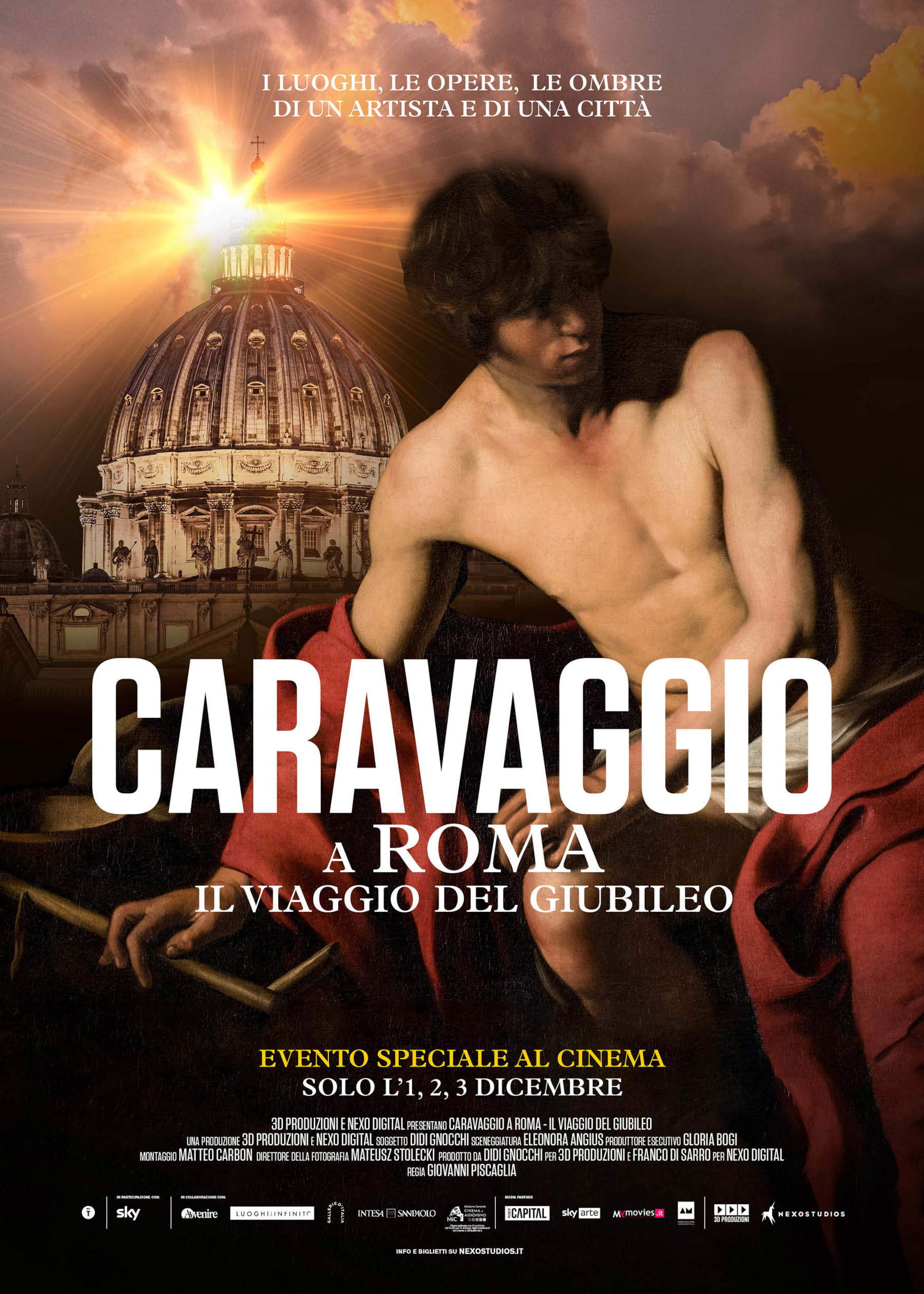

We receive and publish this review, written by a reader who preferred not to sign himself, on the film Caravaggio in Rome. The Journey of the Jubilee, in Italian theaters from December 1 to 3, 2025.

It is a special event that lands in cinemas from December 1 to 3: Caravaggio in Rome. The Jubilee Journey, directed by Giovanni Piscaglia. The brainchild of Franco Di Sarro, with a screenplay by Eleonora Angius on a subject by Didi Gnocchi.

The film is made by 3D Produzioni and Nexo Studios in participation with SKY, and in collaboration with Avvenire and Gallerie d’Italia-Intesa Sanpaolo. A remarkable production that is immediately apparent in the cinematography, editing and soundtrack. The same can be said overall for the image quality except, inexplicably, precisely for some photographs of paintings, for which the effect, amplified by the big screen, is somewhat that of scanning from a paper volume.

Beyond the technical aspects, the documentary, with a certain celebratory tone proper to the genre, explores the spiritual dimension of Michelangelo Merisi (1571-1610) in Jubilee Rome. A journey back in time that leads from the contemporaneity of today’s pilgrims to the seventeenth century, where the life of a restless genius was formed and lost.

Not a film entirely about Caravaggio, then, as many fans might expect. In the words of art critic Claudio Strinati, the Lombard artist is “a painter of feeling, and the Jubilee is feeling, not reasoning.” And it was just during the Holy Year of 1600 that Merisi found his consecration, presenting to the public two large canvases he had been working on since the previous year, the Vocation and the Martyrdom of St. Matthew, which changed art history and his life forever.

From that moment on, Caravaggio’s painting was never the same: he abandoned scenes of everyday life to devote himself almost exclusively to the sacred, transforming art into a mirror of an intense and tormented faith, steeped in mercy and a deep need for redemption. This urgency was felt even more after he killed a man and was exiled from the Eternal City, when his works became somber and dramatic, as seen particularly in those painted in Naples, Malta, Syracuse and Messina. Incidentally, the documentary ignores the latter two stages, but we have become accustomed to seeing the Sicilian period neglected, as was also the case in the recent exhibition Caravaggio 2025.

With his appeals for forgiveness going unheeded, the painter died a sinner, attempting to return to Rome, waiting for a pardon that he failed to obtain. Between light and darkness, guilt and forgiveness, the film aims to restore the intimate portrait of a man capable of discerning beauty even in sin. A fragile and universal artist who, in the Jubilee opened by Pope Francis, returns to move with the timeless power of his poetics.

For the benefit of the general public, which is always much attracted to the fictional aspects, the narrative persists, now untenable, of a Caravaggio who used prostitutes well known in the papal capital, and therefore easily recognizable, as models for the Virgin Mary. On the other hand, the total silence on the only altarpiece that the artist painted, in Rome, entirely in the Holy Year of 1600 is surprising: that painting “cum figuris,” as indicated in contemporary sources, which has been identified as the Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis, destined for an oratory in Palermo from which it was stolen in 1969. The latter is undoubtedly a relatively recent novelty, but that is not why it should escape a documentary. It only remains to reflect how certain popular products intended for the small and large and screen always find a limitation in their tendency to rely on “generalist” authors, rather than involving specialists in the various topics addressed for the occasion.

The film makes use of numerous contributions, and among the interviewees should be mentioned at least the director of the Galleria Borghese Francesca Cappelletti, historian Franco Cardini, sculptor Jago, director of the Galleria Nazionali di Arte Antica Palazzo Barberini-Galleria Corsini Thomas Clement Salomon and art historian and director of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence Msgr. Timothy Verdon.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.