We have reached stop number twelve in our journey through Italian museums in search of animals, creatures and fantastic places. This time the itinerary stops in Le Marche in search of presences in the region’s museums. Here’s what we found! The project is carried out by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture to promote attendance at museums, safe places suitable for everyone (families, children, friends, couples, colleagues, individual visitors... ), through a different point of view.

According to Greek mythology, he was the winged horse that was tamed by the hero Bellerophon, and accompanied the latter in the enterprise that led him to defeat the Chimera, another fantastic creature. Also according to the myth, Pegasus is said to have struck Mount Helicon with a hoof, causing a spring called “Hippocrene” (i.e., “horse spring”) to gush forth, which later became sacred to the muses. Here, we see Pegasus in a pair of fine gold hoop earrings, worked in a twist: the ancient goldsmith who made these two pieces worked the entire front to give it the shape of the winged horse. This is an elegant production of goldsmithing that can be approximated to Eastern Mediterranean workmanship: it was found in the tomb of a woman, along with other jewelry, in the Montefortino necropolis of Arcevia. According to experts, it is an object dating back to the late 3rd century B.C. and demonstrates the quality of goldsmith production that had been achieved in the area at that time.

The National Archaeological Museum of the Marches preserves a sumptuous Roman sarcophagus from around 150 AD, where the entire story of Medea is told. The most famous version is the one told in Euripides’ Medea: the sorceress Medea had helped Jason and the Argonauts conquer the Golden Fleece, and the two were united in love. After a few years, however, Jason abandoned Medea to marry Glauce, daughter of the king of Corinth, Creon: Medea took her revenge by making Glauce and Creon die atrociously, and killing, though tormented by grief, the children she had with Jason, and then flew off to Athens in the chariot of the Sun. The sarcophagus, discovered in the 15th century, was considered so important in ancient times that even Pieter Paul Rubens drew it during one of his stays in Rome (it was in fact on view at the Cortile delle Statue del Belvedere in the Vatican: it would come to Ancona only in 1927 following an acquisition to enrich the collections of the city’s nascent Archaeological Museum). One of the sides of the sarcophagus depicts a large griffin: this legendary creature had the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle, and in ancient times was considered a creature sacred to the Sun god. This, then, is why it is found reported in a sarcophagus telling the myth of Medea.

An omphalos (a term that can also be translated into the Italian “onphalo,” and literally means “navel”) is a carved stone that in ancient times had important religious value (it was in fact typically placed in the central and most sacred part of an ancient shrine, usually dedicated to the god Apollo: the most famous omphalos of Greco-Roman antiquity was that of the sanctuary at Delphi), and it could be decorated with scenes, figures, and ornamental motifs. We do not know where theomphalos now preserved at the State Archaeological Museum in Urbisaglia was used, but given the presence of the two sphinxes (the fantastic creatures that had the head and breast of a woman, the body of a dog, the wings of an eagle, the paws of a lion, and the tail of a snake) it is speculated that this stone was also linked to the cult of Apollo: at the sanctuary of Delphi there were in fact two large sphinxes above two tall columns, which had the function of guardians of the temple.

In ancient Greece a large wine cup made of pottery was called a kylix, which had the shape of a flat cup, with two handles on either side: the bowl, very wide and thin, rested on a slender foot, and was decorated both in the lower part and in the central part, the part that was filled with wine. This one preserved at the State Antiquarium of Numana, of Attic production, is a kylix with a white background and black figures, with a rounded profile, an interior that is entirely black (with the exception of the central roundel where a discobolus is depicted), and an exterior decorated with figures of satyrs, intent on playing, some the lyre and some the flute. Since the kylix was used during banquets, it was normal for it to be decorated with scenes that hinted at times of feasting, idleness, and amusement: this work is no exception, with the satyrs, half-man, half-goat creatures, giving themselves to music.

From Roman times we have come to us so many oil lamps: they were the most widespread lighting tools in the Roman world. They could be made of earthenware, bronze, or other materials, had a rounded body that served as a reservoir for fuel (typically oil, which was inserted through a feeding hole), a handle, and a spout (although sometimes there could be more than one spout). All kinds of them were produced and were usually decorated with a variety of scenes: the one preserved at the Archaeological Museum in Ascoli Piceno depicts a satyr, a fantastic creature with a body half man (the upper part) and half goat (the lower part) and with goat horns, next to a fantastic animal, a kind of dragon. The satyr is intent on playing a tibia, the typical double flute, while the animal is lying down and looking at him: since satyrs were often depicted riding fantastic animals or assorted monsters, it is likely that here the anonymous author of this oil lamp simply wanted to depict the two creatures together at a time when the satyr is not riding the animal, but taking a moment to play.

Among the halls of the Rocca Roveresca in Senigallia it is also possible to find some sphinxes: the current conformation of the castle is in fact due to Giovanni della Rovere, who was lord of Senigallia between 1474 and 1501 and had among his symbols also the wingless sphinx, crowned by seven snakes joined by a ribbon with the inscription, “Hinc nostras licet estimare,” or “from here it is right to estimate our (virtues).” Completing the motto is another phrase: “Seram haec semper nec mors mihi seva negabit”; that is, “I will always preserve them, nor will cruel death take them from me.” John cherished the sphinx since he considered himself a new Oedipus capable of acutely defeating the evil cunning (the serpents) of the sphinx who, having been overcome, throws herself off the cliff (thus without wings that can protect her) into which travelers fell who, on the route to Thebes where the sphinx was located, were unable to solve the question posed by her. Man’s intelligence accomplishes, therefore, a victory over death itself. John, according to this mentality, embodies Renaissance virtus: what was accomplished in life delivers to posterity, by memory, the immortality of the valiant man, and the Rock is an example of this.

This St. Michael, by the Sienese painter Andrea di Bartolo (Siena, c. 1360 - 1428), is part of a dismembered polyptych: the archangel is depicted on a gilded background, under a polylobed pointed arch, and with his typical iconographic attributes: the armor (in this case also gilded, extremely refined, and covered by an iridescent red cloak edged with gold), the spear, and, of course, the dragon, which in this refined painting is held down precisely with the tip of the spear. The dragon, in paintings featuring St. Michael as the protagonist, is the symbol of the devil, of the devil, of evil, which was defeated by the angelic hosts commanded precisely by the archangel Michael: that is why in ancient paintings this saint is always depicted as a strong, handsome and elegant knight. This work is distinguished by its soft colors, the fineness of its details, and its preciousness, all typical features of the Sienese school to which Andrea di Bartolo belonged: he was the son of another great local painter, Bartolo di Fredi, and had studied by observing the works of Spinello Aretino and Simone Martini.

The panel with the Miracle of the Profaned Host is one of Paolo Uccello’s most famous works and, in one of the compartments into which the story is divided, features two devils. The work, painted between 1467 and 1468 as the predella of the altarpiece with the Communion of the Apostles executed by Giusto di Gand for the church of Santa Maria di Pian di Mercato of the Corpus Domini confraternity of Urbino, recounts an event recounted by the chronicler Giovanni Villani in the 14th century, and which took place in Paris in 1290: the protagonist is a Jewish usurer, who buys a consecrated host from a woman (first episode). The Jew and his family set fire to the host, which miraculously begins to bleed, drawing the attention of some guards (second episode). The host is then re-consecrated (third episode) and the sacrilegious woman who had sold it is executed (fourth episode), and the same happens to the Jew and his family, who are put on the stake (fifth episode). Finally, in the sixth and final episode, devils and angels vie for the woman’s soul. The story thus reflects the extremely negative opinion in Europe at the time about Jews. The work, explains scholar Andrea Bernardini, “is painted in Paolo Uccello’s mature language, characterized by fantastic shapes and colors and his original perspective inventions.”

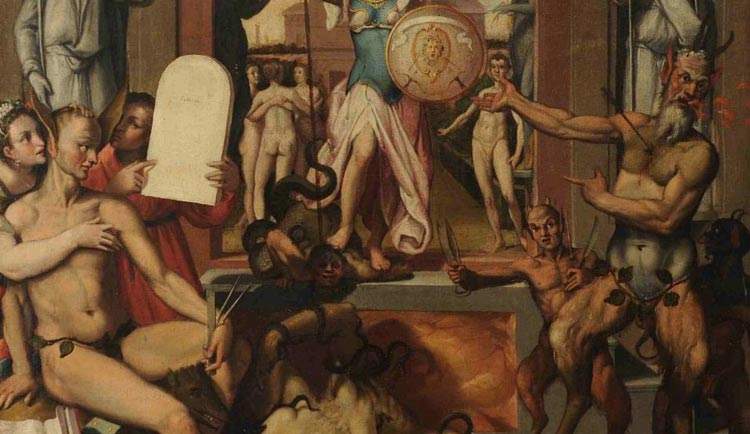

This singular and unique work by Federico Zuccari (Sant’Angelo in Vado, 1539 - Ancona, 1609) came about as a result of an incident that aroused the author’s indignation. In 1581 the artist had been commissioned by Paolo Ghiselli, scalco of Pope Gregory XIII, to create a work for the family chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Baraccano in Bologna, with the subject being the procession of Gregory the Great. Neither Ghiselli nor the Bolognese artists liked the work, so the artist was mocked and humiliated, and Ghiselli decided to turn to another artist, Cesare Aretusi. To make up for the disgrace he had suffered, Federico Zuccari painted, together with Domenico Cresti known as the Passignano, a huge cartoon, the Porta Virtutis, which on St. Luke’s Day (the patron saint of painters) in 1581, was displayed on the facade of the church of the painters’ guild. During the exhibition, Zuccari explained the work to all present: however, the gesture got him into numerous legal troubles. A small-scale painted version of the large original cartoon, which the artist would later give to Duke Francesco Maria II Della Rovere, is preserved in Urbino. It is an allegory of the painting environment in Bologna: the large arch in the center is the door of virtue, where we see Minerva, goddess of wisdom, standing guard over the door to ward off the creatures that symbolize negative qualities. These are the monstrous creatures we see at her feet and some animals: the boar and the fox are symbols of ignorance, the woman tormented by snakes is envy, and the fire-breathing satyr is the minister of envy. Above her, fly the four qualities of art (drawing, coloring, invention, and decoration), symbolized by four angels who carry Federico Zuccari’s altarpiece in triumph, while the personification of conceit shows the ignorant king, King Midas characterized by donkey ears (referring, of course, to the patron), the worst quality altarpiece, but which will later be chosen by the patron.

The town of Castelli, in Abruzzo, is one of Italy’s main centers of pottery production: the workshops of the artisans who produced the majolica developed mainly between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (although the earliest modern works by Castellian potters date from the fifteenth century). It was, however, between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that the most important workshops were born and grew, handing down the business from generation to generation: these included the Gentili workshop, to which the author of this pottery in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, namely Carmine Gentili (Castelli, 1678 - 1763), belonged. Castelli’s ceramists were distinguished by their colorful works (almost always in shades of blue and yellow), depicting even complex scenes, such as this Galatea being carried out to sea by a triton: Galatea was a Nereid, or sea nymph, and is often depicted together with her companions or fantastic creatures of the sea. The merman, seen here below together with a large fish as he tries to touch one of the other nymphs, was a half-man, half-fish sea creature: these beings, all belonging to the offspring of the god Triton, son of the god Poseidon and the nymph Amphitrite, fulfilled the role of servants of the sea deities.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Marche |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.