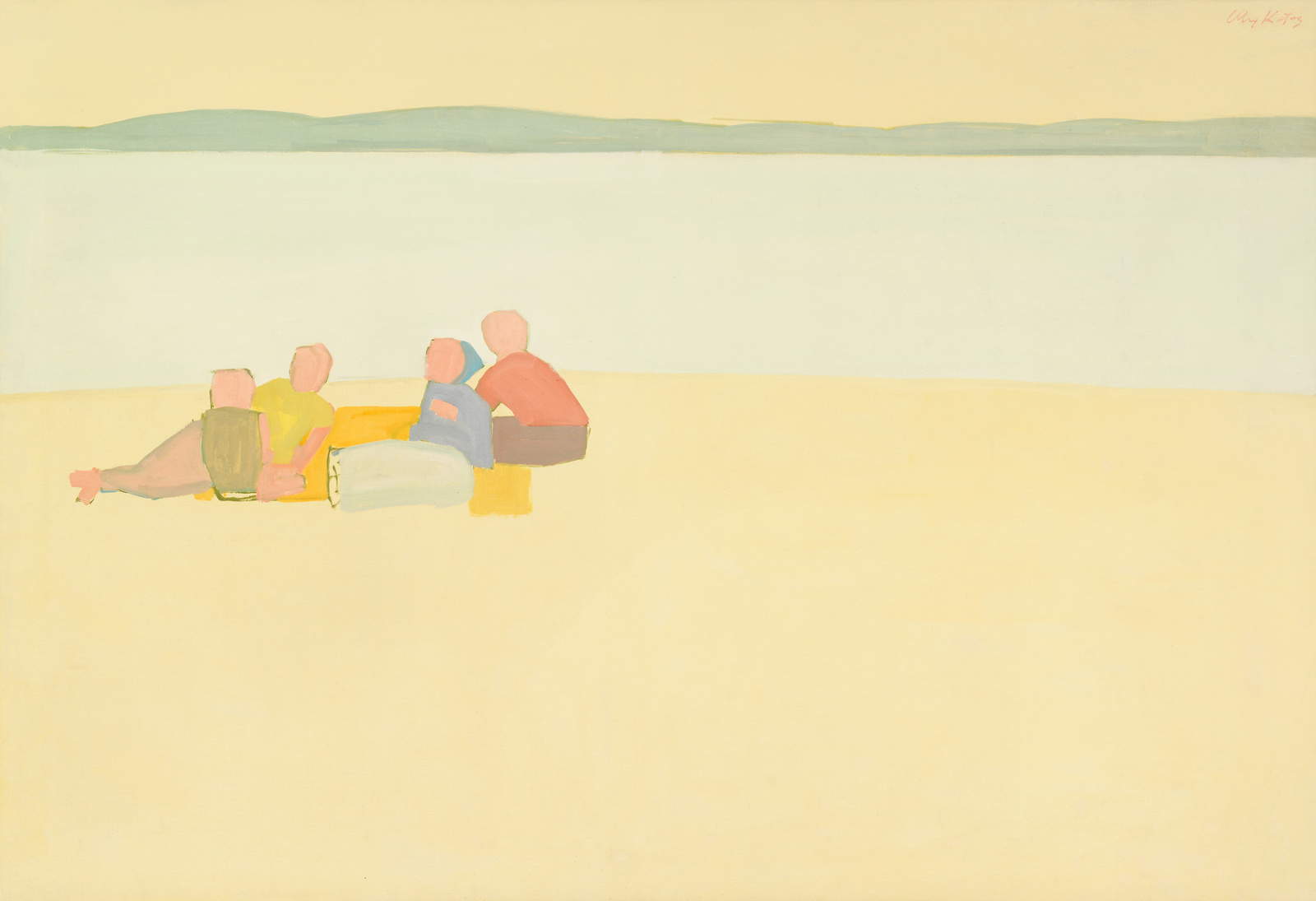

In the painting of Alex Katz (New York, 1927), one of the leading names in American New Realism ,summer never ends. It is not, however, a summer as we understand it in Italy: if anything, Katz’s summer should be thought of as a quiet one, far removed from mass vacations, as a world distilled of blinding light, elegant figures and silence. Although his fame is inextricably linked to the monumental portraits that redefined figure painting in post-World War II America, his Maine beaches and seascapes represent an equally fundamental chapter in his artistic quest.

The geography of these works has its epicenter in Lincolnville, Maine, where the artist has spent his summers since 1954, a time when he also began painting his first “beach” works, although in fact the bulk of his production on beaches begins in the 1990s. However, to understand his sensitivity to the coast, his innate ability to capture the sensory richness of light, temperature and winds, one must go back to his childhood. Katz grew up in St. Albans, a quiet neighborhood in Queens, New York, just a few miles from the Atlantic Ocean. It’s easy to imagine how that landscape of brackish marshes, small islands and bright beaches imprinted itself on the young artist’s mind, explaining what painter Peter Halley, in a short essay written for a 2002 exhibition of Katz’s work at the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery devoted specifically to his beaches, calls a “Venetian luminosity,” an affinity for the expansiveness and style of a Veronese. That childlike light is the same as that found, decades later, on the shores of Maine.

Maine is not merely a subject for Katz, but a condition of the soul and the gaze. The American artist’s eye usually focuses on primary elements: water, sky, horizon line, vegetation and, above all, light: Katz’s is a cold, Atlantic light, which does not warm but reveals, which does not caress shapes but carves them with precision.

Often associated by convention with Pop Art, Katz actually pursues an exquisitely painterly goal, succeeding in reconciling the abstraction and realism of postwar American art in a style he himself calls “thoroughly American.” His figuration is essential and intense; the images are elemental, luminous and direct, expressed through sharp planes of color and a two-dimensional perspective that, while devoid of sentimental connotations, communicates a deep psychological resonance. His painting, between the 1950s and 1960s, developed as a reaction both to Abstract Expressionism, whose gestural violence and expressiveness he rejected, seeking, on the contrary, to be as least expressive as possible, and to Pop Art, to which Katz responded by focusing on scenes of everyday life, but rereading them with the aesthetics of commercial illustrations.

The real protagonist of these works is the treatment of light. Katz makes it an almost solid entity, a blade that flattens everything, eliminating intermediate shadows and reducing landscape and figures to pure chromatic silhouettes. It is a light that freezes time, so much so that in his canvases the bathers are practically never individuals caught in a moment of leisure, but essential forms embedded in a rigorous composition. They do not interact with each other in a conventional way; their physical proximity does not imply an emotional connection, but responds to a need for formal balance. This feeling of detachment is accentuated by the monumental scale of the canvases. By reproducing intimate scenes on billboard formats, Katz creates a perceptual short-circuit. The immediacy of the subject clashes with the monumentality of the execution, forcing the viewer to reconsider the image not as a window to the world, but as an autonomous pictorial object.

However, this does not mean that there is no deeper investigation in his beach scenes. “One can also easily observe that Katz,” Halley wrote, “in his paintings of beaches, has documented the massive middle-class migration to the coasts that has been going on since he was a young man in the 1950s.” And the artist has a “keen eye for coastal sociology.” But there’s more: “In some ways, Katz himself never struck me as one of these water-bound immigrants. His sensitivity to the sensory richness of the coast-its light, temperature, and winds-is too great and somehow marks him out as a native of this environment. Katz seems to have his beaches, his marshes and the ocean beyond them at the core of his being.”

Many of these compositions arise from photographs of the beach, while others are derived from studies of the figures taken from life. And the figures that populate these beaches are often members of his inner circle: his wife and muse Ada, his son Vincent, friends and other artists. Yet even when portraying his closest loved ones, Katz maintains an unmistakable analytical coolness. They are stylized presences, and their interiority remains inaccessible. They become part of the landscape itself, structural elements of the composition. In this, his painting departs radically from the psychological introspection of an Edward Hopper, with whom he has sometimes been superficially compared. If Hopper painted loneliness as an existential condition, Katz paints being alone as a given, a state of stillness that needs no dramatic interpretation.

Alex Katz’s beaches are ultimately sophisticated exercises in style about seeing. They represent the deconstruction of an archetype, namely the beach day, with all that goes with it, in order to reconstruct it according to a new visual lexicon. The artist does not ask the viewer to feel the warmth of the sun or the sound of the waves, but to observe how light defines an edge, how one color juxtaposes with another, how a composition of figures can generate a visual rhythm. It is a world of flawless surfaces that celebrate their own, magnificent, two-dimensionality. A perpetual, motionless summer, fixed forever in the crystalline, relentless light of painting.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.