There are places intwentieth-century art where reality suddenly seems to open up, multiply, slip out of its usual form. All it takes is a mirror, a sheet of glass that, instead of returning a faithful image, betrays it, doubles it, reinvents it.

The mirror stops being a domestic object and becomes a threshold, a gap between what it is and what it could be. Each step in front of its surface changes the story of the work, prolongs it, distorts it. It is like entering a room where the world does not end: it replicates itself.

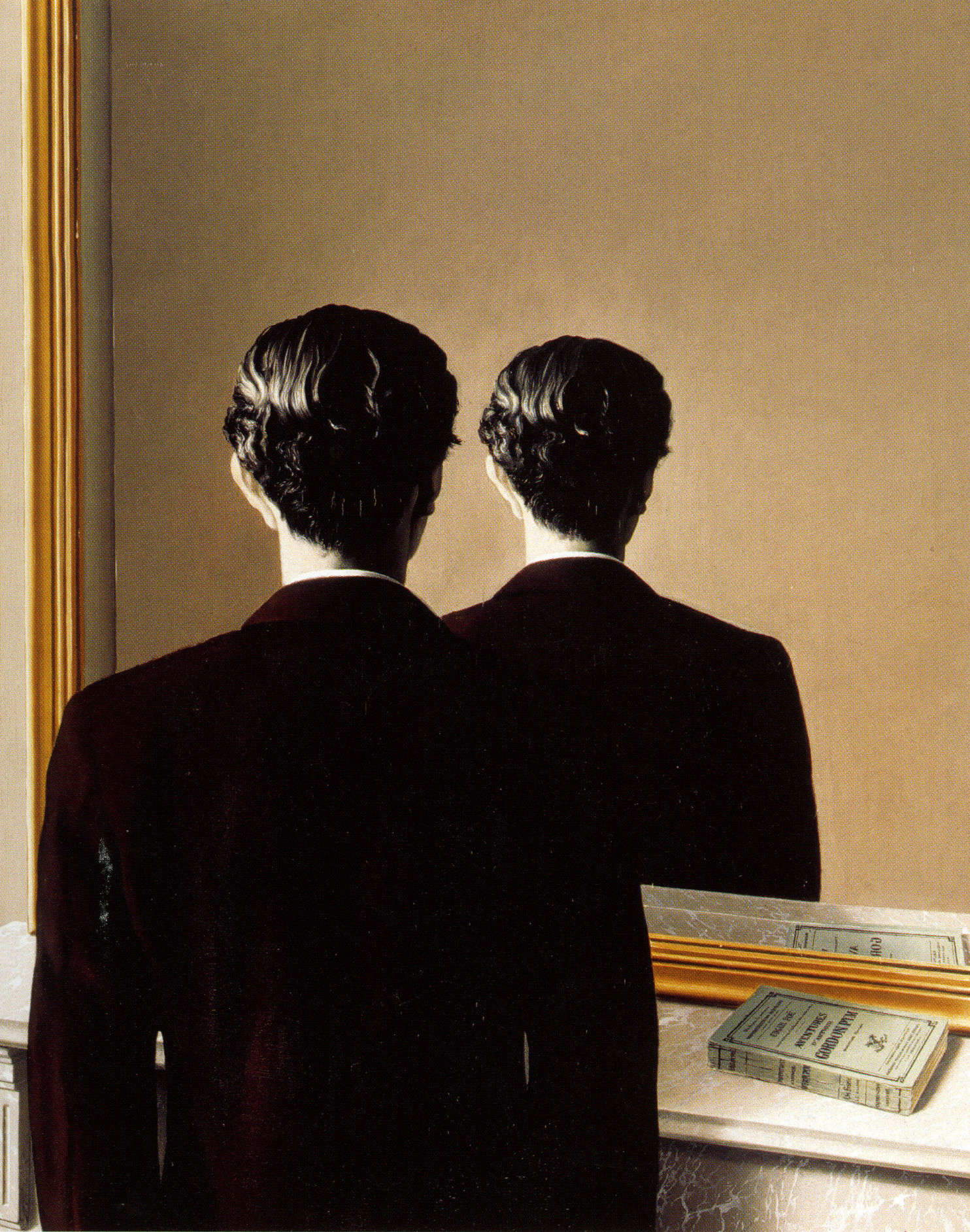

The first great protagonist of this revolution is René Magritte, who in 1937 painted La Reproduction Interdite. A man, seen from behind, looks at a mirror: but the glass returns not his face, but still the back of his head. It is a silent, almost cruel reversal. The mirror does not reflect: it betrays. It shows that the image is never a guarantee of truth, that seeing is not the same as knowing. Magritte uses the mirror to undermine trust in the real and to suggest that identity and perception are unstable constructions, always threatened by enigma.

In the same decades, photography appropriates the mirror to transform reality into reflection. Man Ray, in the 1920s and 1930s, uses it to split bodies, make them float, create compositions where the figure seems both presence and ghost. With a mirror, Man Ray constructs a world that does not exist, but appears possible: an alternate reality that coexists with our own. Then comes the post-World War II period, and art begins to put the viewer at the center. The mirror changes function: it no longer merely duplicates reality, but constructs it together with the beholder.

In the 1960s, starting in 1962, Michelangelo Pistoletto made his famous Quadri specchianti, silkscreened silhouettes on polished steel plates that integrate the viewer into the image: the beholder becomes part of the work, and the boundary between art and everyday life dissolves. Here the mirror is both a political and poetic statement: the work lives only if someone looks at it, and each moment changes its content. It is an art made of the present, of shared moments. Soon after, Lucas Samaras built the Mirrored Rooms (1966): rooms entirely covered with mirrors, where the visitor finds himself trapped in a vortex of centerless reflections. There is no stable point from which to look: identity becomes fragment, diffuse presence. The mirror does not return a “self,” but a whole constellation of possible selves. In the 1970s architecture and art intertwine in the work of Dan Graham, with installations such as Public Space/Two Audiences (1976), of reflective sheets and semi-reflective glass that create environments in which the beholder is observed, the beholder becomes visible and invisible at the same time. The mirror becomes a social device: it reveals power relations, the tension between being and appearing, between privacy and exposure.

The twentieth century also saw the contribution of the minimalists. Robert Morris, with works such as 1965’s Untitled (Mirrored Cubes), uses mirrors to make sculpture disappear into space, transforming the object into pure perception. The reflective material dissolves boundaries and forces the viewer to wonder where the work ends and the world begins.

At the end of the century, the legacy of the mirror as a tool of disorientation and immersion was picked up by artists such as Yayoi Kusama, who as early as 1965 with Infinity Mirror Room-Phalli’s Field introduced reflective environments capable of causing the viewer to lose spatial coordinates. Although her production extends into the 21st century, her entry into the art scene occurs fully in the 1960s. In these rooms one senses the birth of a new idea of infinity: not mathematical, not conceptual, but sensory. The mirror becomes the universe.

Crossing the century, we understand that the mirror in art has never been incidental. In the Surrealists, in the Minimalists, in immersive installations, the mirror becomes concept and matter together, a tool to interrogate space, the body, perception. Each work with the mirror is an invitation to look beyond, to see what is not immediately visible, to recognize the multiplicity of reality and of our experience of the world.

Today, when we move in front of a mirror, even a simple or domestic one, we can hearthe echoes of these researches: it is no longer just a matter of reflecting a face, but of multiplying points of view, of recognizing the fragmentation of reality, of perceiving the multiplicity of space and time, inside and outside of us. Through the twentieth century, the mirror has become a symbol of participation, of transformation, of the relationship between perception and reality. It is the tool that reminds us that reality is never unique, that every glance is experience, and that art can teach us to see beyond what immediately appears to us.

To enter a mirror today is therefore to enter into a dialogue with the past and with ourselves: with the avant-gardes that invented the language of reflections, with Magritte’s enigmas, with Kusama’s infinite rooms, and with the multiplicity that the twentieth century taught us to read. It is to understand that every reflection is possible, every multiplication is experience, and that art, like the mirror, never ceases to give us back new visions.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.