Galileo Galilei and Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli were very good friends: they were almost the same age (the scientist was born in 1564, the artist in 1559), they had met in Florence when they were young, and a strong friendship was born between them, which lasted all their lives, partly because they both cultivated the same passions. Galileo loved to spend his free time making drawings, and Cigoli, for his part, had considerable interests in science and astronomy.

|

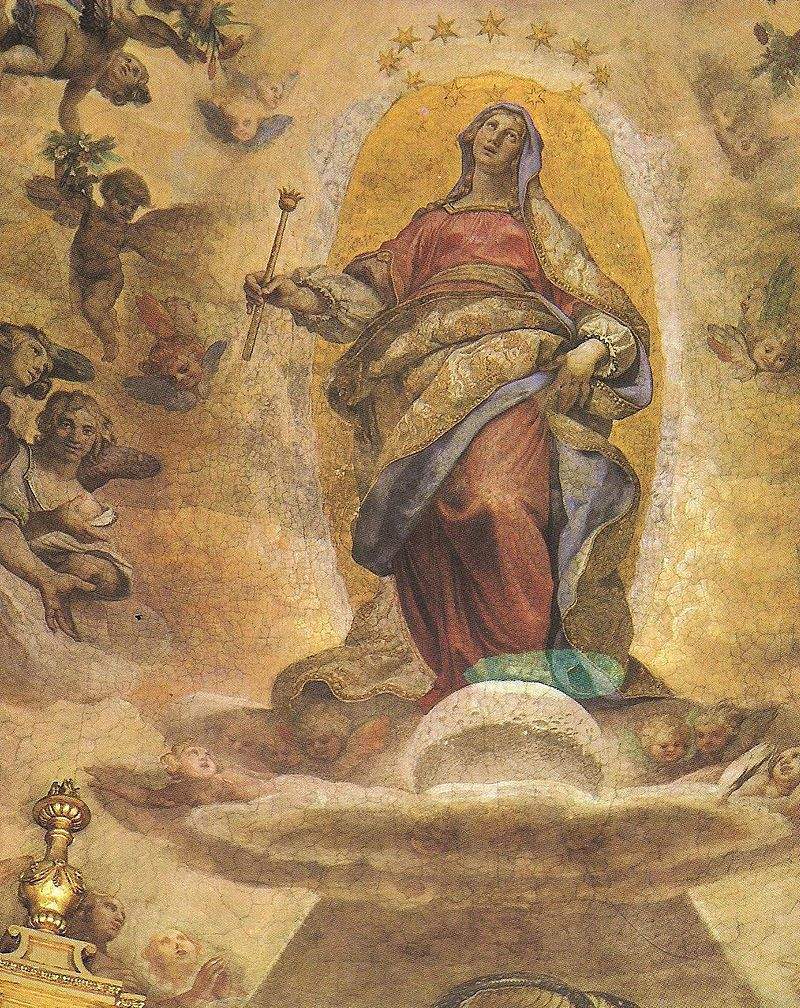

| Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli, Frescoes of the Pauline Chapel; 1610-1612; Rome, Santa Maria Maggiore. Photo credit. |

We are left with a dense correspondence: the letters that have come down to us cover a time span from 1609 to 1613 (the year of Cigoli’s death) and were published in 2009 in a volume published by Edizioni ETS (on the blog Letteratura artistica you can find a nice article on this correspondence). It was through this friendship that one of Cigoli’s greatest and most modern masterpieces would come to life: the fresco known as theImmaculate Conception in the Pauline Chapel inside the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.

Cigoli obtained the commission directly from Pope Paul V, born Camillo Borghese: this was in 1610. It should be specified, however, that the original document with which Cigoli was commissioned the work did not strictly speak of the Immaculate Conception. The subject was in fact supposed to be the woman of the Apocalypse, an iconographic theme very similar to that of the Immaculate Conception. Here is what the document stated, “In the dome the vision of Revelation ch. 12 will be painted, that is, a woman clothed with the sun, under her feet the moon, around her head a crown of twelve stars. I meet St. Michael the Archangel in the form of a fighter. Around the three hierarchies distinguished each in three orders: underneath at the bottom baits a serpent with a crushed head, as in Genesis ch. 3. Around them the twelve Apostles.” So how is it possible that this woman was later identified with the representation of the Immaculata? To understand this, it is enough to continue reading the document: “Such woman signifies and the Church, as Andrea Cesariense wants, and St. Methodius, and Our Lady as St. Bernard in the said chapter 2 with many Latins, and literally no less signifies the Church, than Our Lady, who from the beginning of the world manifested with the Incarnatione to the Angels, fights to the end of the World triumphing in heaven.”

|

| The Immaculate Conception painted by Cigoli |

|

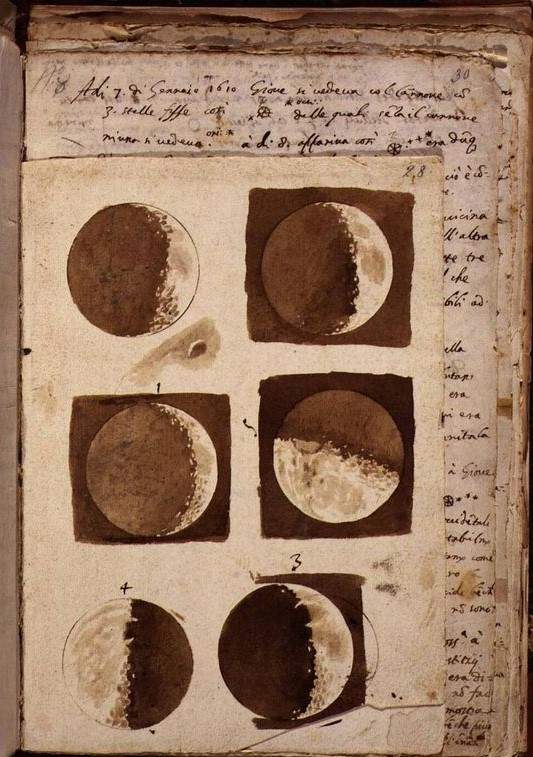

| Galileo Galilei, Astronomy. Observations of the Lunar Phases, November-December 1609 (1609; autograph paper manuscript, watercolor drawings on paper, 33 x 23 x 1.7 cm; Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, ms. Galilean 48 |

So, the woman of Revelation, described, precisely, in chapter 12 of the book of Revelation of John in the ways in which we see her described in the document, would allude, according to many theological interpretations (including that of St. Bernard quoted in the document) precisely to Our Lady. And from this vision then derives the traditional iconography of the Immaculate Conception, which, though with different variations, in its basic elements has always remained unchanged throughout the history of art: the twelve stars symbolizing the tribes of Israel but also the twelve apostles, the serpent representing the defeated evil one, and the white robe symbolizing purity. To these symbols is added that of the moon, which has a complex meaning: suffice it here to think of the fact that, in those days, the Aristotelian conception, espoused by the Church, of the moon as a perfect, smooth and incorruptible star was still taken at face value: thus a symbol, among others, of the purity of the Madonna.

When Cigoli finished his work in 1612, however, the moon that the patrons saw before their eyes was anything but perfect, smooth and incorruptible. Two years earlier, the same year that Cigoli began his work, Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius, his famous treatise on astronomy in which, in Latin, the Pisan scientist published many of his discoveries, was being given to the press. Among these were the discoveries about the surface of the moon: through his observations, Galileo had in fact noticed that the lunar surface had craters, depressions, and mountains, which from our planet appear somewhat like spots dotting the visible surface of the moon. Cigoli was aware of these discoveries, and thought to visually account for them in his fresco. So much so that in 1612, the scientist Federico Cesi, who founded theAccademia dei Lincei and was a friend of both, wrote a letter to Galileo in which he said that Cigoli “s’è portato divinamente nella cupola della cappella di S. S.ta a S. Maria Maggiore, e come buon amico e leale, ha, sotto l’immagine della Beata Vergine, pinto la Luna nel modo che da V.S. è stata scoperta, con la divisione merlata e le sue isolette.” It was, in short, the first acknowledgement, in art, of Galileo’s discoveries, as well as a masterpiece of absolute modernity that brought inside a papal basilica, and in a work commissioned by a pope, those innovations that would later be opposed by the Church itself: only three years later, the scientist would be denounced to the Holy Office, and his troubles with the Inquisition would thus begin.

How, then, is it possible that the fresco was not, in some way, censured by the ecclesiastical authorities? Quite simply, the attitude that the upper echelons of the Church preferred was one of prudence rather than censorship. In the oculus of the dome in which Cigoli’s fresco is painted, one can in fact read this inscription, “Mariae Christi Mater Semper Virgini Paulus V P.M.,” or “Pontiff Paul V [dedicates] to Mary, mother of Christ, ever virgin.” Thus there are no direct references to belief in the Immaculate Conception, although the dedication makes it explicit that the figure of the woman in Revelation should be interpreted precisely as Mary, the mother of Christ. The Church, therefore, preferred to avoid clarifying the meaning of the symbolism adopted in the painting.

What, then, is the correct way to refer to this painting? There are scholars who continue to call it Immaculate Conception. Others opt for a more “neutral” Assumption of Mary. Still others refer to the original document and prefer a generic Woman of the Apocalypse. The fact remains, however, that Ludovico Cardi’s fresco is the first work in the history of art to represent the moon according to Galileo Galilei’s discoveries, which thus entered the temple of those who were shortly to become his greatest opponents. And the work’s importance is also enhanced by the fact that there were then a great many artists who later decided to represent the moon in this way.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.