The relationship between Vasily Kandinsky (Moscow, 1866 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1944) andItaly is a complex affair, made up of missed encounters, long-distance admiration, and fruitful reworkings that in some ways marked the history of 20th-century art in our country. To this relationship, often described as fertile but far from peaceful, the MA*GA Museum in Gallarate has dedicated the exhibition Kandinsky and Italy (from November 30, 2025 to April 12, 2026, curated by Elisabetta Barisoni and Emma Zanella), organized in collaboration with the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. The great Russian artist, as is well known, played a crucial role in the renewal of visual languages, and his lesson was received, sometimes challenged and finally assimilated, by generations of Italian artists, from those active in the 1930s to the protagonists of the post-World War II period.

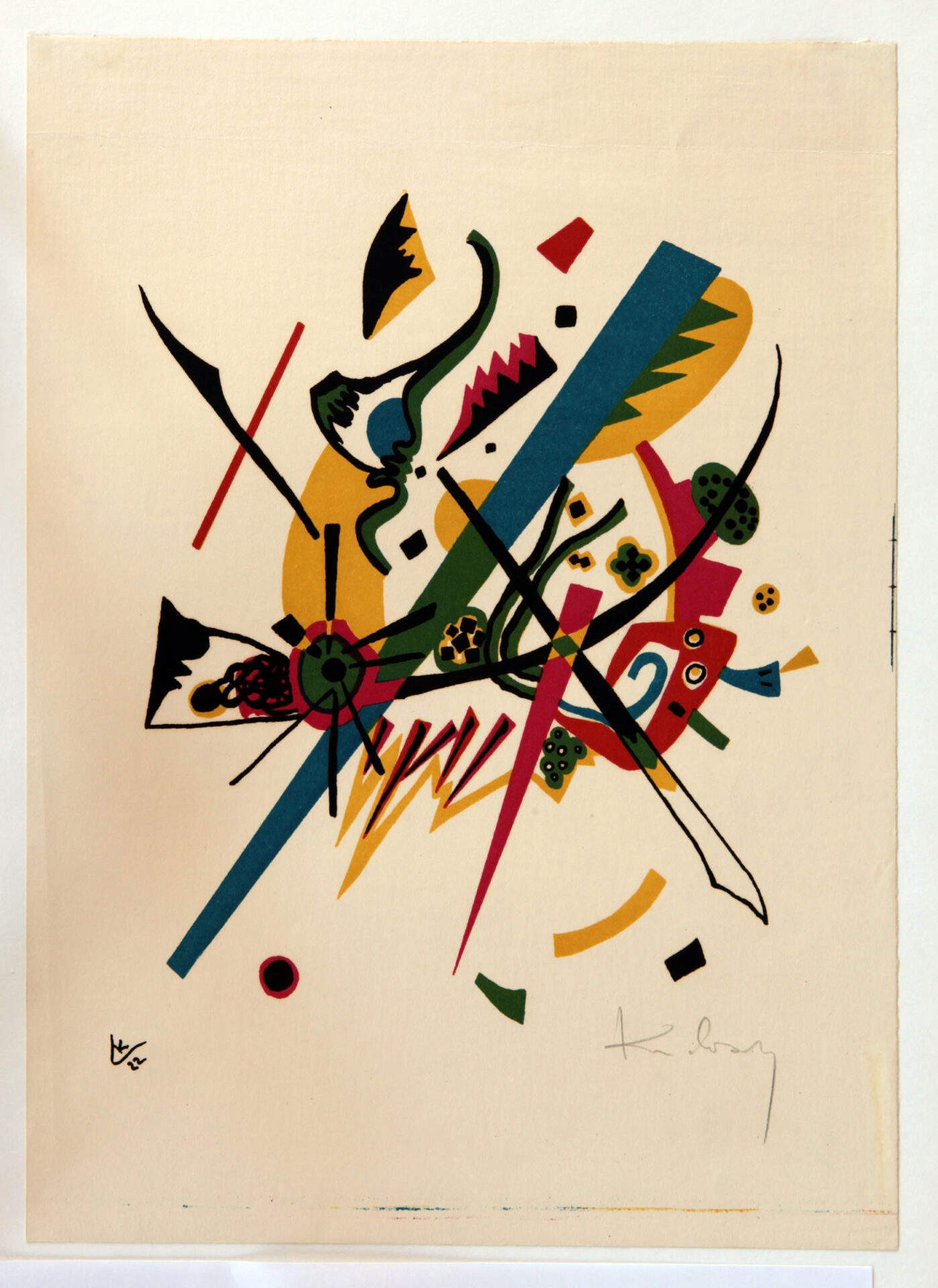

To understand the scope of this dialogue, it is necessary to go back to 1934, a year that marks a fundamental watershed in early 20th-century Italian artistic culture. In that spring, Galleria Il Milione in Milan, directed by the Ghiringhelli brothers, opened Kandinsky’s first solo exhibition in Italy. The event was made possible thanks to the mediation of the rationalist architect Alberto Sartoris, who had long had an epistolary relationship with the artist and who had personally gone out of his way to promote his work in the Italian context. Kandinsky, who at the time was living in Paris after the forced closure of the Bauhaus and the rise of Nazism in Germany, sent to Milan forty-five watercolors, thirty drawings made between 1922 and 1933, and the complete series of etchings entitled Small Worlds. The decision not to exhibit oil paintings was dictated by logistical and economic reasons, but this did not diminish the historical importance of the event, which offered the Italian public an opportunity to engage directly with the theories and practice of the father of Abstractionism.

The 1934 exhibition was not just an exhibition, but a sort of cultural manifesto that caught the attention of Milanese (and Italian all) art circles and sparked heated debates. Indeed, around Galleria Il Milione gravitated a group of young artists and intellectuals determined to close the gap between Italian art and the European avant-garde. Figures such as Lucio Fontana, Osvaldo Licini, Fausto Melotti, Atanasio Soldati, and Luigi Veronesi found in Kandinsky’s works a confirmation of their research and a stimulus to break free for good from the dominant figurative tradition and naturalism. However, the reception was not without misunderstandings. While Kandinsky’s work was admired for its formal freedom, his insistence on the spiritual and mystical dimension of art clashed with the aspirations for order, clarity and rationality that characterized much of Italian Abstractionism in those years. A central role in this debate was played by Carlo Belli (Rovereto, 1903 - Rome, 1991) an art theorist and critic whose famous essay Kn, published in 1935, was defined by Kandinsky himself as the “gospel of so-called abstract art.” Belli argued for the absolute autonomy of art from reality, stating that art should not represent anything outside of itself. However, substantial differences existed between Belli’s and the Russian master’s positions. While Belli attributed to Kandinsky a tendency toward symbolism, the artist politely but firmly rejected this interpretation, making it clear that he never intended to do symbolist painting, but to work exclusively with shapes and colors without wanting to tell stories. Despite these theoretical misunderstandings, Belli had the unquestioned merit of recognizing how Kandinsky’s painting was totally free from the weight of the object and naturalism, living from an autonomous spirit and perfect balance.

Kandinsky’s influence was particularly felt in the context ofComo Abstractism, where artists such as Manlio Rho, Mario Radice and Carla Badiali developed a language that, while looking to Europe, maintained a strong specificity. These artists, often from the world of industrial production and textile design, declined the lesson of abstraction in a pragmatic and constructive sense, dialoguing closely with the rationalist architecture of Giuseppe Terragni. Manlio Rho (Como, 1901 - 1957), for example, found in the books of the Bauhaus and in the writings of Kandinsky a source of inspiration for integrating the formal needs of art with those of production, pursuing an ideal of unity of the arts. In his works, abstraction is constructed through the superimposition of planes and geometric forms, in a dynamic balance that excludes all realistic references. Mario Radice (Como, 1898 - Milan, 1987), who collaborated with Terragni on the decoration of the Casa del Fascio in Como, also experimented with a language made of balance and open compositional possibilities, far from mere decorativism.

While a rigorous abstractionism linked to architecture was being consolidated in Como, in Milan artists such as Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968) and Fausto Melotti (Rovereto, 1901 - Milan, 1986) explored different paths, focusing on sculpture and the use of innovative or poor materials such as concrete, iron and plaster. Fontana’s abstract sculptures of 1934, made of iron wire or colored concrete, broke with the static and monumental tradition, literally drawing in space and anticipating postwar spatialist research. Bruno Munari (Milan, 1907 - 1998), with his “Useless Machines,” introduced the element of movement and lightness, freeing abstract forms from the static nature of the painting and placing them in relation to their surroundings. Osvaldo Licini (Monte Vidon Corrado, 1898 - 1954), an atypical and solitary figure, mixed an interest in abstraction with a lyrical and visionary vein, rejecting the certainties of Milanese rationalism to praise doubt and imagination.

The dialogue between Kandinsky and Italy suffered a setback with the outbreak of World War II, but resumed with vigor in the postwar period, when the need for cultural and moral renewal prompted new generations of artists to look again to the masters of the European avant-garde. The 1948 Venice Biennale marked an important moment with the exhibition of three paintings by Kandinsky from Peggy Guggenheim’s collection. But it was the 1950 edition, curated by Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, that definitively consecrated the Russian artist with a major retrospective that presented to the Italian public the evolution of his style, from his early figurative works to his mature abstract compositions. On that occasion, the City of Venice purchased the 1922 work White Zig zags for the Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro, an act that sanctioned the official entry of International Abstractionism into Italian public collections.

In the climate of postwar reconstruction, groups such as Forma 1 in Rome and MAC (Movimento Arte Concreta) in Milan found in Kandinsky’s writings and work an indispensable point of reference. For the artists of MAC, founded in 1948 by Gillo Dorfles, Bruno Munari, Atanasio Soldati and Gianni Monnet, the texts Dello spirituale nell’arte and Punto, linea, superficie offered a methodological basis for rethinking abstract painting as a universal language. However, their adherence was not uncritical: to Kandinsky’s mysticism, MAC contrasted a more rationalist and planning approach, attentive to dialogue with design and architecture. Atanasio Soldati (Parma, 1896 - 1953), forerunner of Abstractionism in the 1930s, represented a linking figure between Kandinsky’s lyrical abstraction and the concreteness of the new movement, introducing in his geometries a dynamism that recalled the Russian master’s theories.

In Rome, the Forma 1 group, composed of Piero Dorazio, Carla Accardi, Achille Perilli and Giulio Turcato, among others, stood in sharp opposition to socialist realism, claiming the autonomy of form and color. For Piero Dorazio, Kandinsky was the “creator of the 20th century,” the one who had saved young painters from the suffocating influence of Picasso and national-popular rhetoric. Dorazio saw in Kandinsky not so much the prophet of a mystical dimension as the founder of a modern pictorial language based on the autonomy of expressive means. The magazine Forma 2, published in 1950 and entirely dedicated to Kandinsky, represented a tribute but also a critical manifesto, recognizing in the Russian master the origin of an abstract genealogy to be renewed and projected into the future.

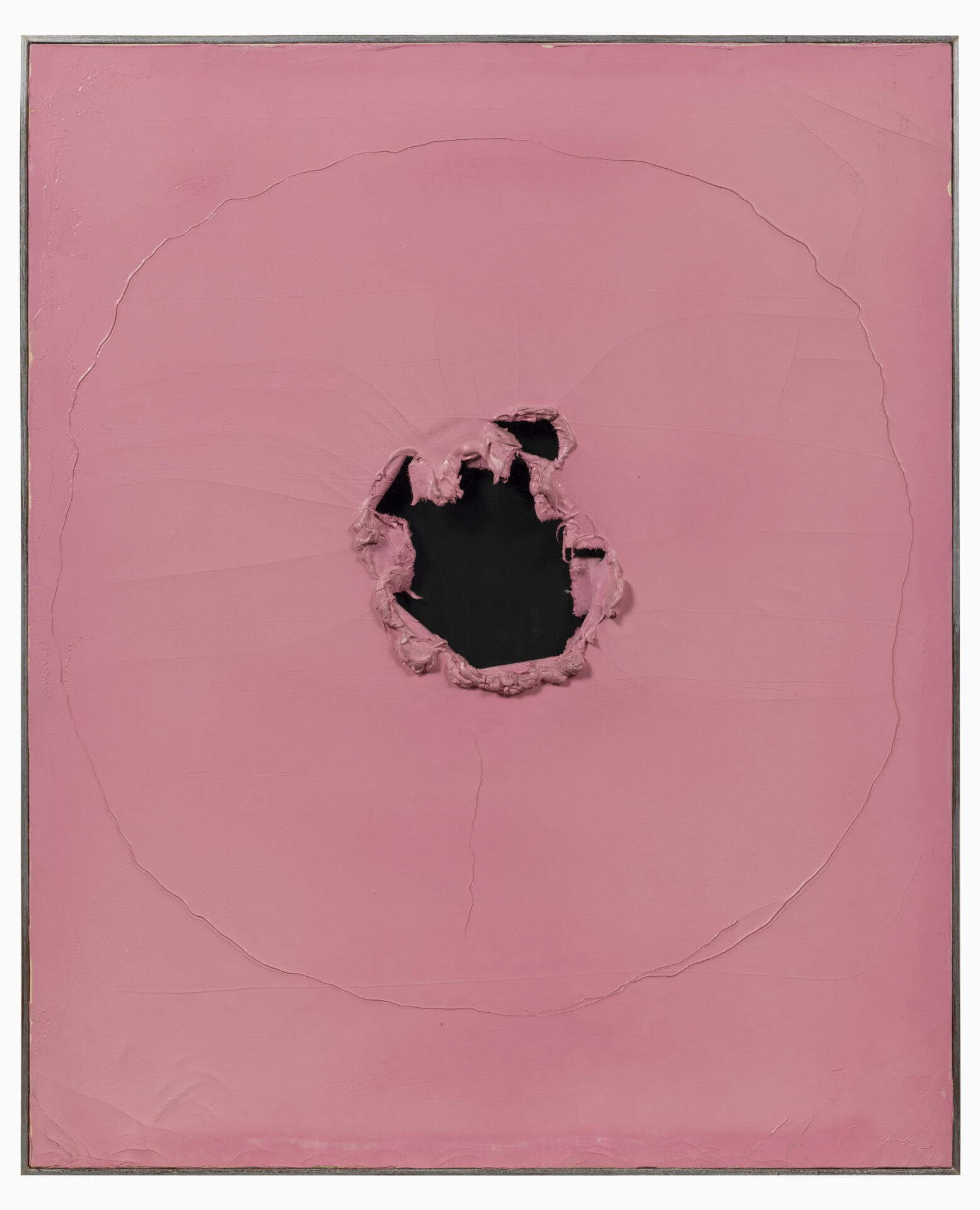

In the 1950s, Kandinsky’s legacy was also reworked by artists working outside organized groups, such as Osvaldo Licini and Lucio Fontana. Licini, in his last creative season, developed a language populated by cosmic symbols and fantastical characters, such as the Amalassunte and the Rebel Angels, which profoundly transformed Kandinsky’s cues into a personal and poetic vision. Fontana, while ideally dialoguing with Kandinsky’s desire to go beyond the surface of things, went beyond the pictorial dimension with his Spatial Concepts, piercing and cutting the canvas to transform it into a concrete threshold to the infinite.

Even within the Informal, Kandinsky’s lesson continued to resonate. Artists such as Emilio Vedova, Tancredi Parmeggiani and Ennio Morlotti transformed the master’s spiritual legacy into gesture, sign and matter. Vedova, in his Geometrie nere (Black Geometries ) and subsequent pictorial cycles, developed a gestural and material painting that, while going beyond controlled geometry, maintained a dramatic and compositional tension indebted to the historical avant-gardes. Tancredi, with his teeming pointillism and lyrical visions, explicitly paid homage to Kandinsky in works that reflected a musical and luminous dimension of color.

A fundamental aspect that emerged from the studies presented at the Gallarate exhibition concerns the specificity of Italian Abstractionism, which did not simply imitate foreign models but knew how to move with critical autonomy. Italian artists read, observed and evaluated Kandinsky, Gropius and Mondrian, adapting their lessons to the sensibility and urgencies of the national context. If Como’s Abstractionism was distinguished by greater concreteness and formal solidity, the Milanese and Roman artists explored more experimental and theoretical avenues, helping to define an original and varied artistic language of modernity.

The relationship between Kandinsky and Italy was thus not simply a one-way process of influence, but a living and sometimes conflicting dialogue. The diversity of the Russian master, a witness to a radical spirituality and formal freedom, represented a challenge and an opportunity for growth for Italy in the Fascist and postwar decades. Kandinsky offered Italian artists a vocabulary and genealogy, opening a space of creative freedom in which different generations could recognize, contradict or surpass him.

Graphics also played a significant role in this history of cultural exchange. The series of etchings Piccoli Mondi(Kleine Welten), created by Kandinsky at the Bauhaus in 1922 and exhibited in its entirety in Gallarate, represents a perfect synthesis of his theories on the correspondence between sign, color and sound. These graphic works, which explore the inner dimension through form and color, were purchased by the Art Library of Milan’s Castello Sforzesco as early as 1934, reflecting an early interest on the part of Milanese institutions.

Then, in the years of the economic boom, abstract and concrete art became an integral part of the Italian cultural landscape, thanks in part to the work of critics and gallery owners who continued to argue the case for modernity, in the complexity of a historical period in which art became the bearer of instances of renewal and freedom, demonstrating how Kandinsky’s lesson, with its tension toward the invisible and the spiritual, continued to fertilize the imagery of artists long after his death in 1944 in Neuilly-sur-Seine. From a comparison of the Russian master’s works with those of his Italian interlocutors, a vivid fresco emerges of an era in which art sought to shape a new world, transcending the limits of traditional representation to explore the infinite possibilities of spirit and matter. Kandinsky, with his painting that aspired to the condition of music and the purity of form, remained for decades a beacon, an inescapable term of comparison for anyone who wanted to take the path of abstraction, leaving an indelible mark on Italian visual culture. As Piero Dorazio wrote in 1966, Kandinsky was the one who saved young painters “from the suffocating influence of Picasso, from his Mediterranean mythology that gives an illusory image of this century and remains glued to the Pillars of Hercules of the Renaissance.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.