It is hard to imagine that the Macchiaioli would have been successful if there had not been a host of patrons behind them, not very numerous but nonetheless ready to support their art, either financially or through less direct support, for example by promoting their knowledge. The Macchiaioli have gone down in history for having revolutionized the Italian art scene in the years immediately following the mid-19th century with their innovative approach to painting, representing an avant-garde with respect to the prevailing artistic trends of the time: their revolution would not have been possible, however, had it not been for those patrons who played a crucial role in the movement’s development and success. The supporters of Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, Vincenzo Cabianca, Odoardo Borrani, and their companions enabled the group to pursue its artistic vision and establish itself as the most advanced tip of the art of the time.

The peculiarity of the Macchiaioli’s network of patrons lies in the fact that it was rather meager and often counted on elements completely unrelated to the group, who could offer sometimes occasional support: however, there was also no lack of individuals who promoted their art over the long term by flanking the group for a long time and also directing its orientations. It should also be considered that the Macchiaioli lived through a moment of profound political and social transformation: the movement was born even before the unification of Italy but only became established from the 1960s, and with theunited Italy, the system of protection that the courts of the Italian states had guaranteed for centuries to artists had definitely come to an end (Telemaco Signorini’s father, Giovanni Signorini, for example, who was also a painter and was among the leading artists in the court of Lorraine at the time of the waning of the preunitary states, had benefited): as these ancient and deep-rooted forms of support disappeared, the Macchiaioli could only rely on their own strength to succeed in imposing their works on a market that was emerging in those years and that was fed mainly by the educated city bourgeoisie that was not bound to traditional tastes, or by some particularly enlightened aristocratic elements that were inclined to support novelties.

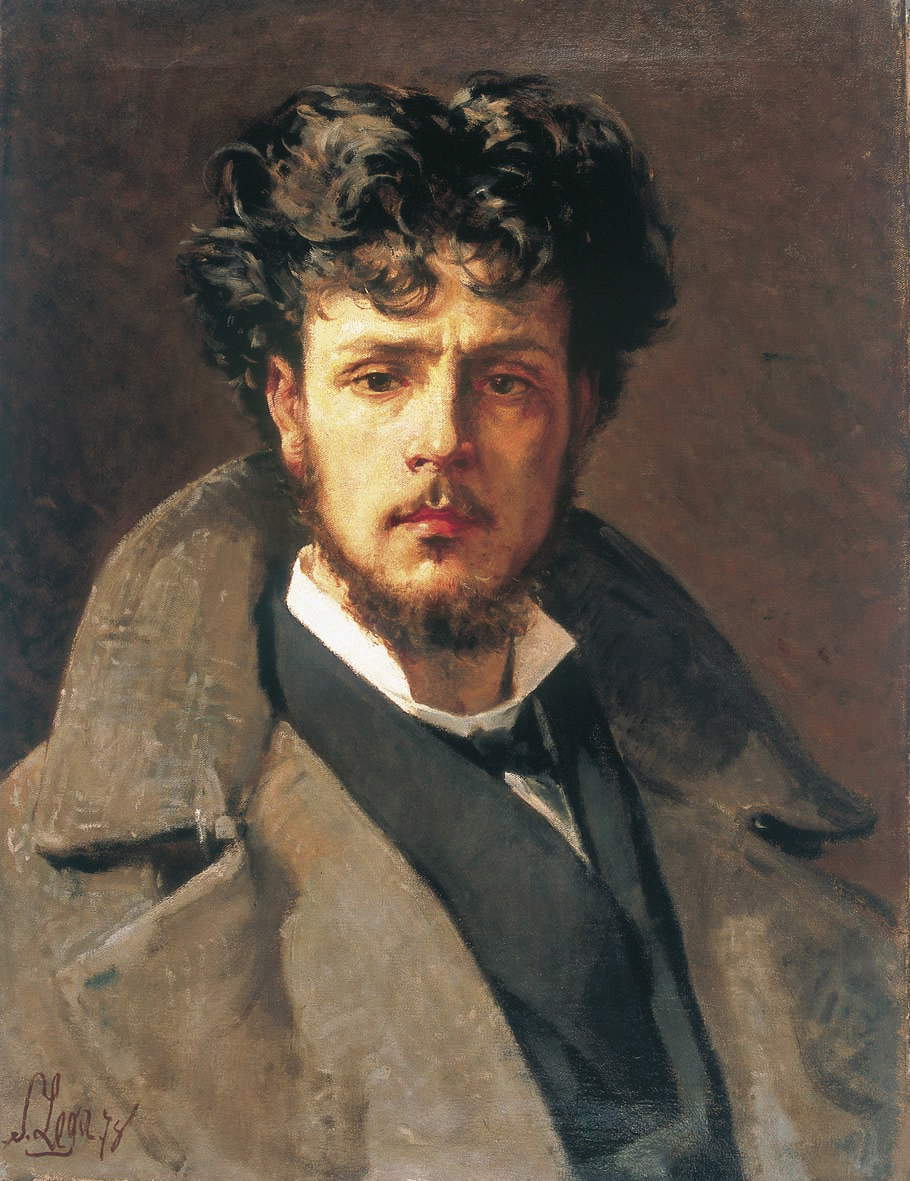

Obviously, the leading roles belonged to the patrons, few in fact, who were convinced supporters of the group and accompanied it for a long time: among them certainly stands out Diego Martelli ( Florence, 1839 - 1896), who was not only an economic supporter of the Macchiaioli, but was also a leading critic who, with his writings, actually “invented” the movement. Martelli, probably the best known of the Macchiaioli’s patrons, came from a wealthy Florentine family and was an art critic, writer and collector.He began to frequent the group very young, not even 18 years old, from the very first meetings at Caffè Michelangiolo in Florence, which, since 1855, had become the usual meeting place for the group’s regulars . This café, located on Via Larga, today’s Via Cavour, “plays in Grand Ducal Florence,” scholar Francesca Dini has written, “the role of an alternative meeting place for intellectuals, patriots and artists who there love to mingle with ’amen chiefs,’ i.e., extravagant types of popular and non-popular extraction, giving rise to a society in which joking and facetiousness hold sway over the most serious discussions and burning current events. In 1855, a new generation of painters who called themselves ’progressives’ made a compact entry there, and whose first goal was to distance themselves from the very institution in which they were trained: the Academy of Fine Arts, with its outdated teachings. The contestation does not specifically concern the Florence Academy in which some of them such as Telemaco Signorini, Raffaello Sernesi, Giovanni Fattori, Giovanni Mochi, and Vito D’Ancona were trained, under the protective aura of the great painter of Italian Romanticism Giuseppe Bezzuoli; it is rather a mental attitude against all Italian academies ’nurseries of mediocrity.’” It was this climate of contestation that fostered the interest of intellectuals and supporters who immediately shared the ideal instances of that group of young people.

Martelli soon switched from intellectual to financial support. In 1861 he inherited from his father an estate in Castiglioncello, on the Leghorn coast, which immediately became the group’s ’summer’ meeting place: indeed, Martelli used to invite all his painter friends, such as Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, Silvestro Lega, Giuseppe Abbati, and Odoardo Borrani, who spent long and productive stays on the Tuscan coast: a presence so assiduous, and made up of artists moved by common and homogeneous intentions, that it even led critics to speak of a “Castiglioncello school” to indicate the artistic community that used to gather here between the 1860s and 1870s. “Diego,” Giovanni Fattori would recall, “out of a feeling of an artist enthusiastic about everything that hinted at progress was with us, and of us younger, rich, free without prejudice, pedantic point welcomed us enthusiastically to his estate, said ’work study there is cloth for all’ and it was a real boem [sic], cheerful well-fed, without thoughts we threw ourselves into art at full throttle and fell in love with that beautiful nature of the great lines serious and classical.”

In addition, Martelli not only offered financial support to the artists but also provided intensive promotion through his writings and criticism. His reviews and articles, published in art journals and newspapers (including the Gazzettino delle arti del disegno, which he founded in 1867) helped to spread the work of the Macchiaioli and introduce them to a wider audience. "The Gazzettino, which offered readers biographies of contemporary Italian and foreign artists, reviews of exhibitions, debates and various chronicles,“ Fulvio Conti wrote, ”qualified itself on the one hand as an instrument for aggregating the various realist schools that had sprung up in various parts of the peninsula on the model of the Tuscan school, and on the other hand as a means of acquainting Italian painters with the new international artistic currents."

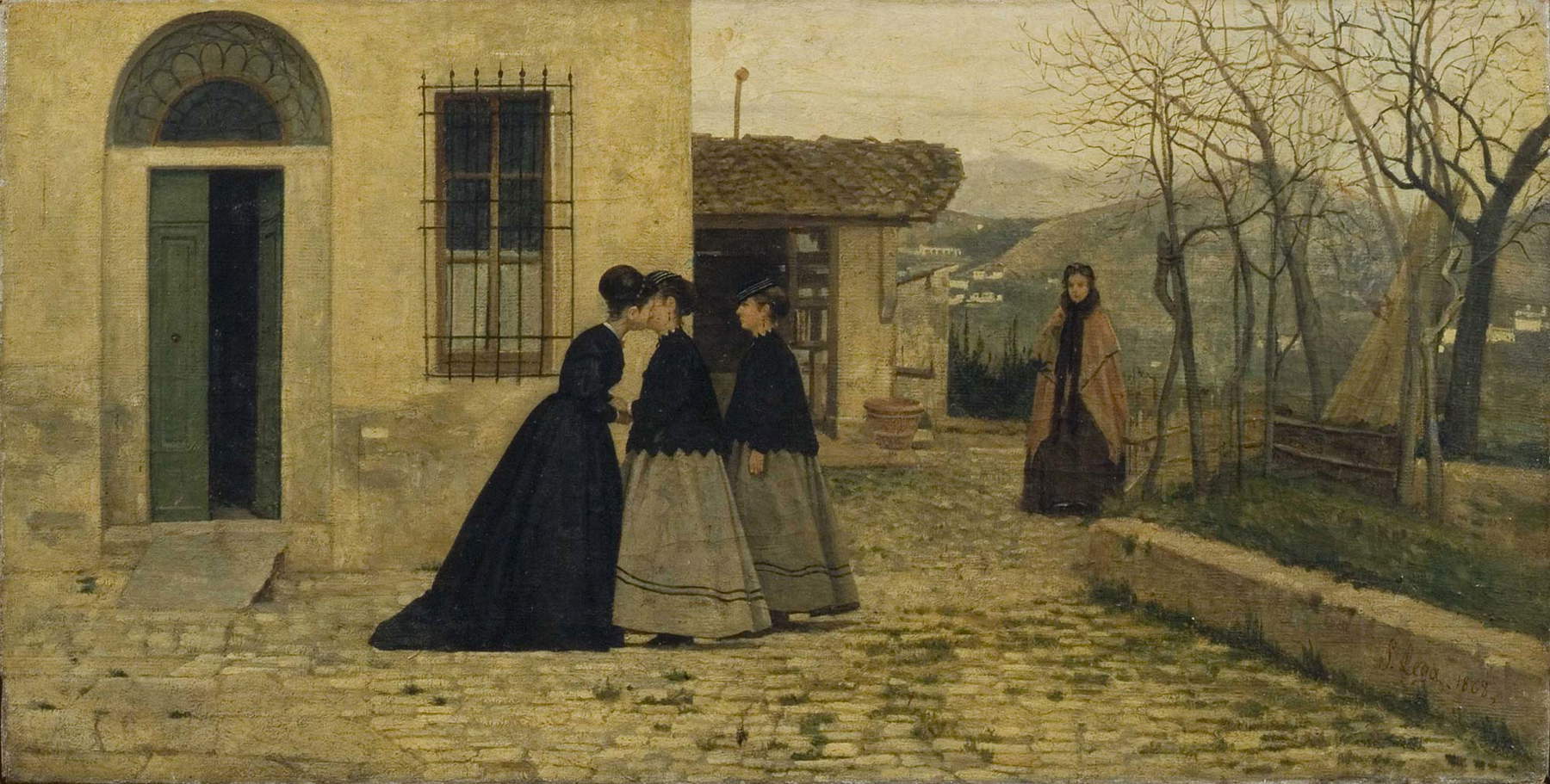

The habit of spending long stays with host families was common to several of the Macchiaioli and was one of the earliest forms of support that ensured that the artists in the group could work with serenity: we could imagine these stays as a kind of modern update of the ancient systems of polite protection offered to artists in the past. Not infrequently, several members of the group stayed at country estates or villas of wealthy landowners who made space and tools available to them so that they could work. The most famous case is probably that of Silvestro Lega, who stayed on several occasions at the estate of the Batelli family (Spirito Batelli was an important publisher at the time), who welcomed the Romagna painter to their estate in Piagentina, in the countryside on the outskirts of Florence, now urbanized: some of Lega’s best-known masterpieces, such as La visita or Il pergolato, were born here. Lega, moreover, had an affair with Spirito’s daughter, Virginia Batelli, who posed for several of his paintings: the girl’s untimely death in 1870 threw the artist into a state of deep depression, which led him to return to his native Romagna. The lives of the Macchiaioli’s patrons often became the subject of their paintings, as Dini still recalls: “The composed elegance of the Florentine bourgeoisie of the Batelli and Cecchini families [another family that supported the Macchiaioli in the same way, nda] is not a simple exterior fact that resurfaces in the sobriety of the calmly hued clothes on which the ladies’ chastened white collars stand out, but it is a fact intrinsic to the painting: it becomes sparse and essential in delineating the wall backdrop of the building, a beautiful rustic fifteenth-century character that the patina of time has coated with a warm golden hue; it becomes embellished in modulating that same hue through barely perceptible chromatic-bright vibrations that translate into a luminous dusting the warmth of that sunny, but not clear, afternoon.”

Several other artists took advantage of thehospitality of families willing to take them in: Signorini, for example, from 1868 was a guest of the De Gori family, which that year commissioned the artist to teach drawing and painting to Giulio, the scion of this lineage of the Florentine aristocracy. Signorini was then a guest several times of the noblewoman Isabella Falconer in her villa in Pistoia, as well as of the Marchesa Vettori in Florence and Montemurlo. It is also possible to mention the Sacchetti family, which offered hospitality to the Macchiaioli since Giuseppe Sacchetti had taken to frequenting members of the group from the very beginning (one of Silvestro Lega’s best-known paintings, I fidanzati, apparently portrays Giuseppe Sacchetti himself along with his future wife Isolina Cecchini). Signorini, by the way, was in this sense among the most ’calculating’ of the Macchiaioli: the Florentine artist, wrote the collector Fabrizio Misuri, “had taken care from the beginning to surround himself with a circle of acquaintances-friends-members. It had not been difficult for him to fit into the circle of the upper middle class elite, nor to endear himself to the refined post-Unitarian aristocracy, thanks to his name, his strong personality, and his being a man of society and good culture.” After all, these frequentations favored commissions and consequently sales: in fact, the Macchiaioli did not disdain to paint on commission. And again, among those who hosted the Macchiaioli on their estates was one of the group’s own painters, Cristiano Banti (Santa Croce sull’Arno, 1824 - Montemurlo, 1904), a Macchiaiolo of the first hour and the author of some of the movement’s best-known pictures (his, for example, is the Riunione di contadine (Meeting of Peasant Women ) in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti).

Banti developed a deep respect for and personal bond with many of the group’s artists (it will be worth mentioning that Banti, along with Signorini and Cabianca, spent a period of residence in the La Spezia area in 1859, which was decisive for the group’s orientations). His career began as a traditional painter (several of his paintings with historical subjects of an academic nature remain, which also earned him a few prizes in the competitions in which he participated), but he soon drew closer to the innovative ideas of the Macchiaioli and became a fervent supporter of their style. Banti, who like Martelli came from a wealthy family, purchased numerous works by the Macchiaioli artists and was instrumental in promoting them. His private collection became one of the most important of the time and helped preserve many significant works. In addition, Banti offered hospitality to the artists in his home, creating a stimulating environment for their creativity. What remains of Banti’s collection is now on display at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti, where a room is also dedicated to Diego Martelli’s rich collection: both Martelli and Banti were, after all, patrons with many traits in common and were probably the closest to the group. As early as 1884, moreover, Adriano Cecioni provided a rather enthusiastic description of Cristiano Banti’s collection: “That Gallery,” the artist pointed out in one of his writings dedicated precisely to Banti, “is unique in its kind, and is, from the point of view of art history, very important, because from some works of the academic school we pass to the first attempts of the macchia, then to the first results, and we arrive up to the present times, which are represented by the second manner of Boldini.”

Another patron fundamental to the movement’s developments was Gustavo Uzielli (Livorno, 1839 - Impruneta, 1911): coming from a family of Jewish descent, Uzielli was a renowned mineralogist, but he also had a deep passion for art. His friendship with Diego Martelli and several members of the Macchiaioli group, including Telemaco Signorini and Adriano Cecioni, led him to become their supporter. Uzielli purchased numerous works of art for members of the group, offering substantial financial support for their projects. His home became a center for intellectual discussion, where science and art met, creating a unique environment that fostered the intellectual and artistic growth of the group. Uzielli was also involved in the intellectual promotion of the group, since in 1905 he took charge of the publication of Adriano Cecioni’s writings, which are still fundamental today for reconstructing the genesis of the Macchiaioli movement.

The role played by some excellent collectors who flanked the group at a later stage, when the careers of the movement’s founders were in their twilight years, should also be recalled: some supporters would prove to be important, however, in spreading knowledge of the work of the Macchiaioli and in supporting in any case the work of the group’s second generation (in which they counted artists of anything but secondary importance, such as the brothers Francesco and Luigi Gioli, Niccolò Cannicci, Ruggero Panerai, Arturo Faldi and others who developed the research of their predecessors). Among the leading names is certainly that of Rinaldo Carnielo (Biadene, 1853 - Florence, 1910), a Venetian sculptor who moved to Florence as a teenager and frequented the members of the group from the 1980s: Carnielo set up a sizeable collection with hundreds of works by Fattori, Signorini, Lega and several other artists, part of which was later donated to the City of Florence. The vastness of Carnielo’s collection contributed in a determinate way to fuel interest in the Macchiaioli. And the same can be said for the collection of another supporter of the group, the Turin businessman Edoardo Bruno, who also moved to Florence: his collection numbered about one hundred and forty paintings, including some of the group’s most famous works such as Odoardo Borrani’s Cucitrici di camicie rosse or Niccolò Cannicci’s later Gramignaie al fiume.

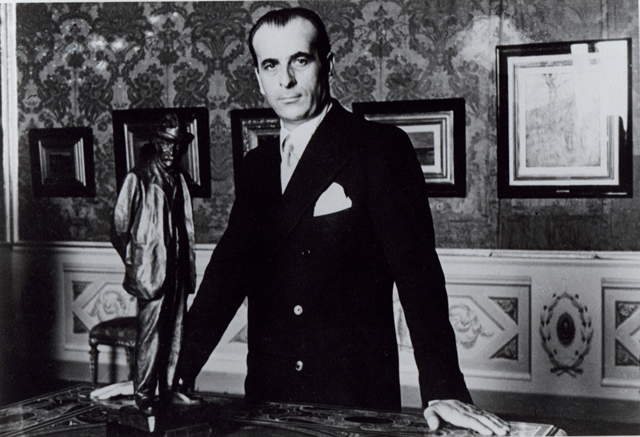

We can then consider some figures who played a dual role, that of collectors of the Macchiaioli and patrons of the post-Macchiaioli: belonging to this important group, which had the merit of raising the interest of the Macchiaioli in the early twentieth century, are collectors such as Gustavo Sforni (Florence, 1888 - Bologna, 1939), a painter and intellectual, coming like so many others from a wealthy family, who was a patron of artists such as Oscar Ghiglia and Mario Puccini, and then the Florentine sculptor Mario Galli (Florence, 1877 - 1946), who was among the most competent collectors of the Macchiaioli on a par with Mario Borgiotti (Leghorn, 1906 - Florence, 1977), who went down in history as “the man of the Macchiaioli” (as an exhibition dedicated to him in 2018 called him), an amateur painter, a refined student of the movement, and a scholar and popularizer who should be credited with a central role in the knowledge of the group. According to Piero Bargellini, Borgiotti was even “the inventor” of the Macchiaioli, since through his activity he rediscovered them “drawing them from the shadows of the bourgeois salons, putting them in the right light in exemplary exhibitions and reproducing them in splendid volumes.” Not, therefore, a patron in the strict sense of the term, but a decisive figure in their knowledge, since with his collection and writings he helped to revive interest in their art at a time in history, the mid-twentieth century, when attention to the Macchiaioli had waned.

The patronage that sustained the Macchiaioli was, in essence, not so widespread, and it took enlightened figures even during the twentieth century for the group to continue to establish itself and be understood as one of the movements that changed the course of nineteenth-century art history. In regard to the Macchiaioli there was initially a certain mistrust, which not infrequently turned into indifference. "Very rare were Diego Martelli’s contemporaries or little posthumans who had encouraged those romantic, hapless, boulevardieres artists," Giovanni Spadolini would even write when presenting an exhibition on the Castiglioncello school.

Yet the ’flankers,’ as it turned out, were not lacking. Indeed: it could be said that this support was crucial to the success of the painters who participated in the group, not least because several supporters did not simply provide financial support or purchase works: some, Martelli in primis, provided an environment in which artists could experiment, grow and share innovative ideas. To these figures, too, the Macchiaioli owe the possibility of having developed a new, original language without being subject to economic constraints that limited their creativity. The role of the few patrons was therefore essential. And while a figure such as Martelli’s has already been widely studied and the terms of the support he gave to his friends are well known, the subject of patronage in regard to the Macchiaioli has nonetheless been little addressed by critics and could constitute for the future an interesting line of research on the activity of this group that revolutionized the art of its era.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.