by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 26/09/2018

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Andrea Mantegna's The Dead Christ is one of the most shocking and revolutionary works in art history. A painting imbued with great humanity. History, dating, events, influences.

On Oct. 2, 1506, Ludovico Mantegna, son of the great artist Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506), sent a letter to the marquis of Mantua, Francesco II Gonzaga (Mantua, 1466 - 1519), in which the painter’s heir (and he himself a painter) proposed to the sovereign the purchase of a work that had remained among his father’s possessions after his death, so that his family could pay off a certain debt. The work mentioned was a Cristo in scurto, or a “Christ in foreshortening,” and would end up the following year in the collections of Francesco II’s younger brother, Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga: there is another letter from Ludovico Mantegna, sent to Isabella d’Este on November 12, 1507, that documents the passage (although the modalities remain unclear to this day). We have no solid certainties or definitive, incontrovertible evidence, but that Christ in Scurto mentioned by Ludovico may be the work that has passed into art history as Andrea Mantegna’s Dead Christ, one of the most dramatic and revolutionary paintings of the Renaissance.

No one before Mantegna had depicted a dead Christ so fiercely dramatic, so extraordinarily human: a cold corpse just laid down from the cross, rather than the son of God awaiting resurrection. Christ’s body is in fact lying on a slab of red marble (this is the so-called Anointing Stone, where according to Christian tradition Jesus’ body would have been prepared for burial: we also sense this from the jar of ointment we see on the edge), and it is barely covered by his shroud, which, except for his legs, leaves everything else uncovered. The relative can thus observe the marks of the wounds left by the nails, which pierced and lacerated the skin of the hands and feet. On the left side of the painting appear three mourners, with faces furrowed by wrinkles and characterized by Mantegna’s hard and harsh mark, shedding copious tears: they are the Madonna, who is wiping her eyes with a handkerchief, Saint John, who is weeping with his hands joined (a detail that increases the tragic nature of his figure), and a woman who opens her mouth in despair, presumably Mary Magdalene. But perhaps, beyond the characters we observe in the scene, the real protagonists of the composition are two elements: light and perspective. The light comes from the right and brings out the stiff folds of the shroud, creating strong contrasts with the shadows, so that the viewer’s attention can be focused on the painting’s starkest details, starting with Jesus’ own wounds: it is a light that almost has a narrative purpose and helps to fuel the drama and emotional participation of the viewer of the Mantegna work. The same can be said for perspective. Mantegna was one of the greatest masters ofperspective illusionism, and he also demonstrates his exceptional skills with the Dead Christ.

Breaking totally with tradition, Mantegna offered a novel representation of the theme of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, experimenting with a point of view that no one before him had ventured to dare. It is as if we were entering the environment in which the corpse of Jesus was transported and Mantegna had wanted to make us direct witnesses of what is happening, placing us in front of Christ, to see him frontally, with slightly elevated point of view. The body of Christ, however, does not appear deformed to us, as would result from a truthful image, from a photograph: to achieve the effects that he was able to achieve, Mantegna had to depart from the canons of Albertian perspective to submit them to his will to create an artifice in order to prevent the body of Jesus from taking on grotesque contours. If the artist had in fact adhered strictly to the rules of perspective, the feet would have been much larger, the head smaller and the body more compressed: on the contrary, Mantegna “came to achieve the adjustment of proportions by empirical means, in order to maintain the due dignity to the figure of Christ” (so art historian Peter Humfrey, who echoes the remarks of scholar Robert Smith, author of important pages on the work of the Venetian artist).

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Dead Christ (c. 1475-1485; tempera on canvas, 68 x 81 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

One of the greatest art historians of all time, Cesare Brandi, also focused on these elements, dedicating an essay also to the Dead Christ, which he called an “extraordinary canvas” that “touches on the absolute without any lenocinio, with an overwhelming severity, so as to constitute the least decorative and almost repulsive painting. A canvas capable of provoking in the viewer a ”coziness“ of ”different feelings,“ which ”ensures a contrasted and almost fearful reception, without, however, arousing pietism of any kind.“ For Brandi, in front of Mantegna’s work ”one can even speak of estrangement, as for an actor.“ This is how the supreme scholar described it: ”the painting is almost a monochrome and constitutes itself normal to the viewer: but singular is the fact that, in the mighty foreshortening [...], there is no illusionism: it is as if the artist paid no more attention to it than to a parallel, instead of normal, depiction to the canvas. Moreover, the structure of the painting is very laborious: Mantegna intended to graduate the penetration of the body into depth, and for this he made use of the folds of the shroud adhering to the body as if it were damp. These folds create as it were secant planes parallel to the soles of the feet and gradually move the body away, so to speak, from space. Light contributes to this result; lateral as in Piero and Masaccio, which for that matter applies more to the shadows than as light: these sink in shaping the body, which thus does not appear shrunken as somewhat happened to Paolo Uccello’s bodies in the Battles, also normal to the surface of the painting, but, in the bold volumetric synthesis and the renunciation of chiaroscuro, compressed into themselves, like the bellows of a bellows. Christ’s hands, not outstretched but with the wrist raised, help the foreshortening of the forearm, while the slight support given to the head by the antique red cushion does not reduce it to a schematic string of nostrils and eyeballs. In short, the whole body is as if segmented by skillful caesuras that slow the flight into depth, and it is as if they elongate it: in the end it does not appear constricted in a space of too little thickness. [...] Remaining in the margin are the two figures of the mourners (but surely the canvas has been trimmed), so much in the margin that Mantegna did not even think of endowing them with greater plastic prominence: in profile they laminate as if lying in the planes of the caesuras that horizontally suggest the folds of the shroud. Thus the picture closes without escape, like a poetic composition, in which the riveted play of rhymes unfolds like the articulation of the overlapping plates of an armor: and the body of Christ is truly assimilated to a body in the armor. Which is what takes away all vagueness and helps give that sense of absolute."

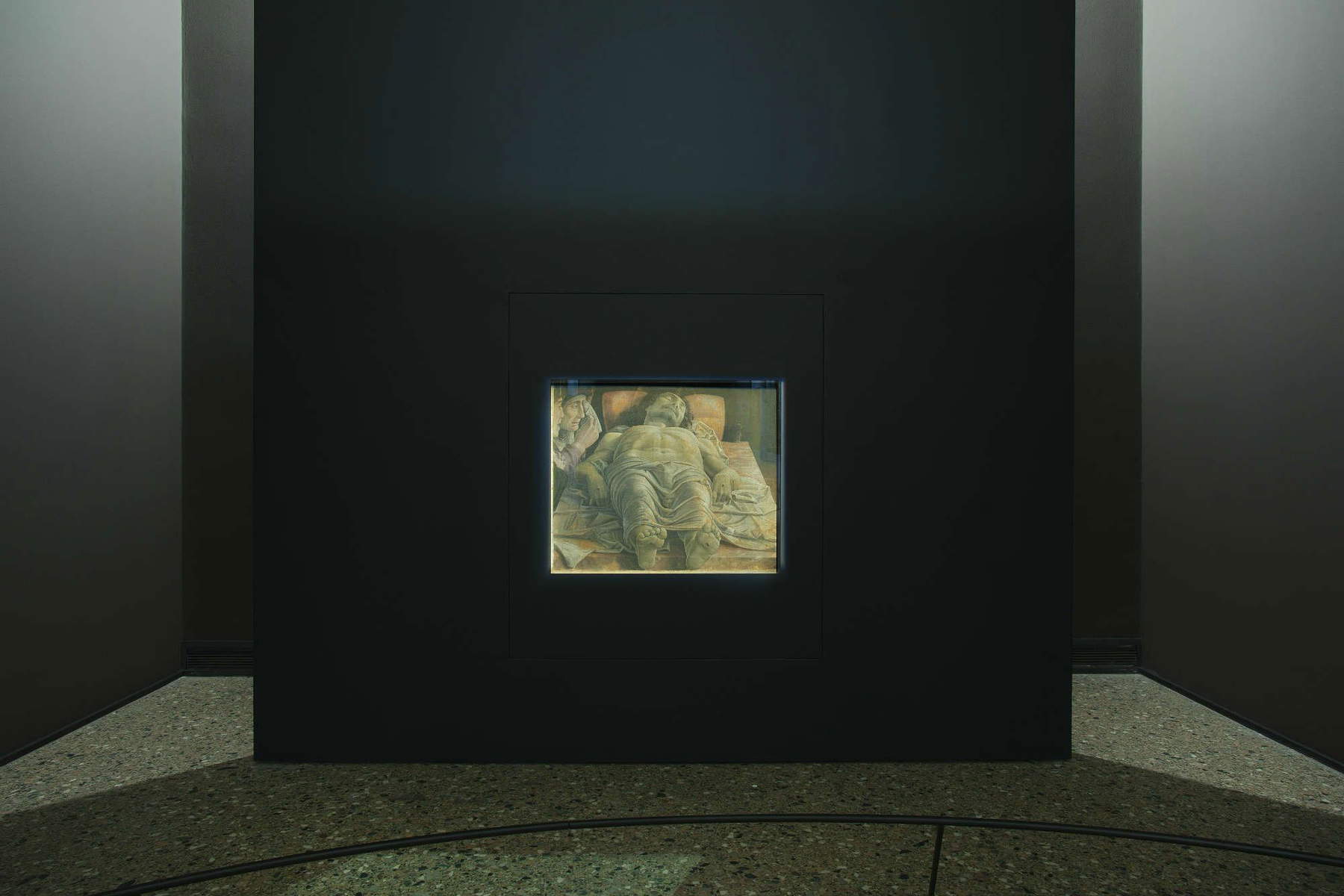

The Dead Christ has, moreover, been the subject of special attention in recent years, since the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, the museum where the work is currently housed, wanted to do justice to its uniqueness by overcoming the location that the painting had maintained until 2013: in fact, Mantegna’s masterpiece was on display, along with other paintings, on the right-hand wall of Room VI, the long corridor dedicated to 15th-century Venetian painting, from which one then accesses the Napoleonic salons. The museum opted for solutions that could give prominence to the work. The 2013 installation was entrusted by Superintendent Sandrina Bandera to the great director Ermanno Olmi (Bergamo, 1931 - Asiago, 2018), who for the Dead Christ imagined a secluded, dark room set up at the end of the corridor, which would have at its center the Mantegna painting alone, placed a few centimeters above the floor (67, to be exact). For the Pinacoteca, Olmi’s project, an official note read, was “the result of a profound intellectual research,” was aimed at isolating and distancing the painting “to allow the correct vision of the particular perspective and chromatic forcing that characterizes it,” and intended to guarantee its vision to small groups of visitors, who would be placed behind a curvilinear spacer “so that the perspective perception” would be “correct” and “the encounter with the work” would be “emotional.” And Ermanno Olmi himself, in an interview published by La Stampa on Dec. 3, 2013, claimed to have placed the work “in the perspective the artist wanted, as indeed Mantegna himself indicates in his testamentary will, at the height where the body was, as it should be looked at.” “To look at it above, as it was before according to the usual museum criteria,” he added, “is an oxymoron, a contradiction that would make even nails rebel. I drowned it in black, in infinite space, in the absolute.” The Bergamasque director’s staging, however, was harshly criticized: according to some critics, it put the work at serious risk of fetishization, made Giovanni Bellini ’s Pietà (placed on the opposite wall as an introduction) almost an accessory, caused the audience to establish a relationship that sought more surprise than insight and knowledge, and made use of a kind of “scenography” deemed inappropriate. Moreover, according to some, the Dead Christ, so placed, gave the idea of being more of a religious icon to be venerated than a figurative text of extreme importance for the developments of Italian art, a situation hardly suitable for a museum of a secular state, and moreover a museum of Napoleonic origin.

In the summer of 2016, the Bandera-Olmi display was dismantled and the Dead Christ underwent a rearrangement: it is the current display, curated by art historian Giovanni Agosti, who received the commission from the Pinacoteca’s director, James M. Bradburne. In particular, the work has been placed on a panel inserted in the center of Room VI, placed at the conclusion of the section on the 15th century to introduce the following century: a solution that, contrary to the one conceived by Ermanno Olmi, has received greater approval.

|

| The old installation (still from a 1999 film by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure) |

|

| The Bandera-Olmi staging |

|

| The Bradburne-Agosti installation. Ph. Credit James O’Mara |

|

| The Bradburne-Agosti installation. Ph. Credit James O’Mara |

It must be stressed, however, that we know very little about Andrea Mantegna’s Dead Christ. We do not even know the date of execution, and in this regard scholars have advanced several hypotheses. Certain stylistic similarities shared with certain elements of the Bridal Chamber have led many art historians to imagine a placement of the Dead Christ shortly after the Mantuan undertaking, which we know ended in 1474: the masterpiece now in Brera could therefore be placed around 1475-1480. This was the opinion of scholars such as Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle (who considered it a work executed immediately after the Camera degli Sposi), Roberto Longhi (for him it was placeable in the eighth decade of the fifteenth century), Ettore Camesasca (who imagined it executed between 1478 and 1485) and many others. Another proposal that has some support is the one according to which the work can be placed between 1470 and 1474, the period in which Mantegna waited for the realization of the scene of the meeting between Ludovico and Francesco Gonzaga in the Bridal Chamber (because of stylistic similarities). Other proposals were unsuccessful, such as those of early 20th-century scholars (above all Paul Kristeller) who considered it to be the work of the Paduan years, or that of Rodolfo Pallucchini, according to whom the painting was to be fixed at Andrea Mantegna’s return from his Florentine sojourns, in 1467. Still others have imagined a later date, in the early sixteenth century, believing it to be a work that the artist executed for his own personal private devotion (in fact, we do not even have any idea who the commissioner was, if there was one). Recently the hypothesis, formulated by Stefano L’Occaso, has gained ground, which would have the painting executed in 1483, on the occasion of the arrival of a fragment of the Anointing Stone in Mantua: it was brought there by Friar Paolo Arrivabene da Canneto, who between 1481 and 1484 was custodian of the Holy Land (i.e., the superior of the Custody of the Holy Land, an entity in charge of the Friars Minor who live and preach in the Middle East, and take care of the reception of pilgrims arriving in the Holy Land: a position that still exists today). It is likely that Mantegna was fascinated by the important relic and decided to pay homage to it in his own way: however, there is no firm evidence, and the dating of the Dead Christ remains an exceedingly complex issue.

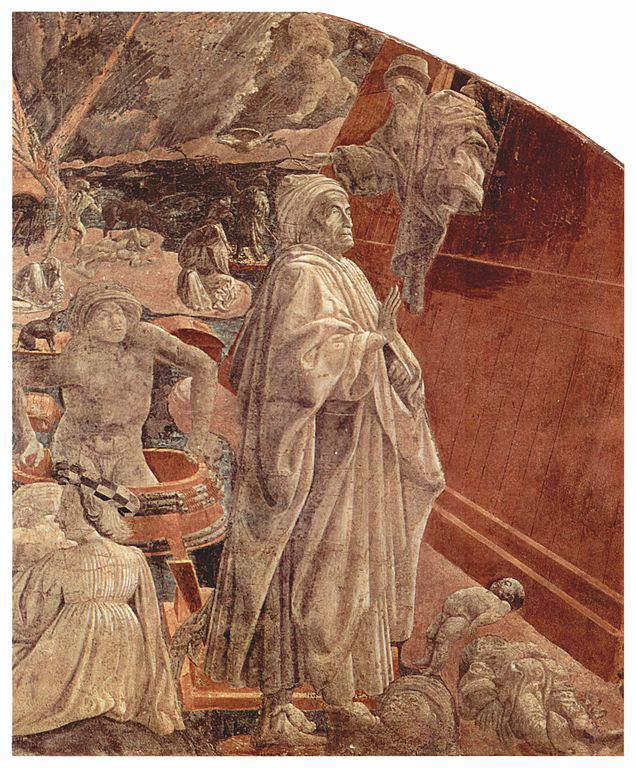

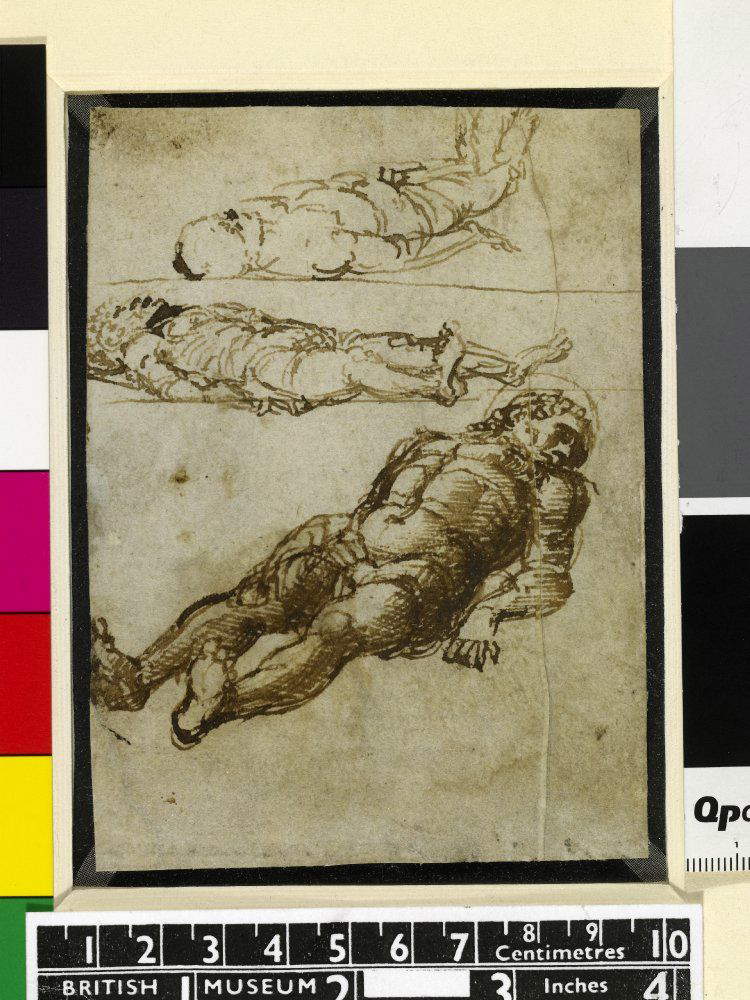

The dating is also made complex by the fact that it is very difficult to find similar works that can provide indications to fix a date that is not already incontrovertible, but at least realistic: it must be reiterated that the range extends over a period of fifty years, and almost all temporal collocations seem plausible. It is, in short, an unprecedented work, although in the history of older art there is no shortage of artists who tried their hand at similar views. Mention must be made of Paolo Uccello (real name Paolo di Dono, Pratovecchio, 1397 - Florence, 1475), who in the Stories of Noah in Santa Maria Novella and the Battle of San Romano inserted foreshortened figures frontally, as would later be Mantegna’s Dead Christ. We know, moreover, that Mantegna got to know the Florentine artist when the latter worked in Padua, in 1445, the year in which the Venetian painter was also in the City of the Saint: in Padua, Paolo Uccello painted some frescoes in Palazzo Vitaliani (now lost), which depicted giants “so beautiful,” as Vasari wrote in his Lives, “that Andrea Mantegna made great account of them.” Certainly the willingness to experiment with daring foreshortenings was never lacking in Mantegna’s art: from the Paduan years, with the body of St. Christopher in the frescoes of the Ovetari chapel, to the Bridal Chamber with its surprising oculus, and finally to the Dead Christ, with which, moreover, two drawings preserved in the British Museum have been associated (one with a further Dead Christ, taken from a slightly different angle, and another with a Man lying on a slab), which could constitute preparatory studies for the Brera painting.

|

| Paolo Uccello, Stories of Noah, The Recession of the Waters, detail (c. 1447-1448; fresco; Florence, Santa Maria Novella) |

|

| Paolo Uccello, Battle of San Romano, Niccolò da Tolentino at the Head of the Florentines, detail (1438; mixed media on panel, 180 x 316 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Mantegna, Transporting the Body of St. Christopher, detail (1454-1457; fresco; Padua, Church of the Eremitani, Ovetari Chapel) |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Oculus of the Bridal Chamber (1465-1474; fresco; Mantua, Castle of San Giorgio) |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Three Studies for the Dead Christ (c. 1475-1485; brown ink on paper, 122 x 88 mm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Man Lying on Plate (c. 1475-1485; brown ink and black chalk on paper, 203 x 139 mm; London, British Museum) |

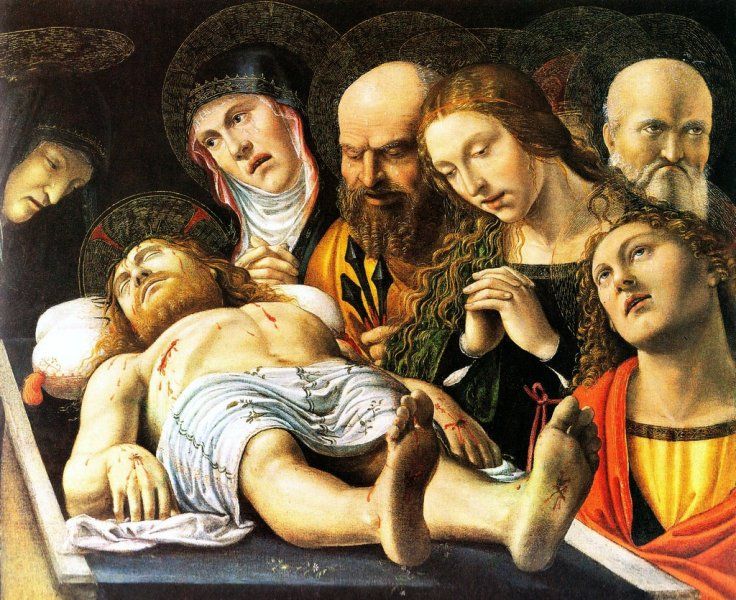

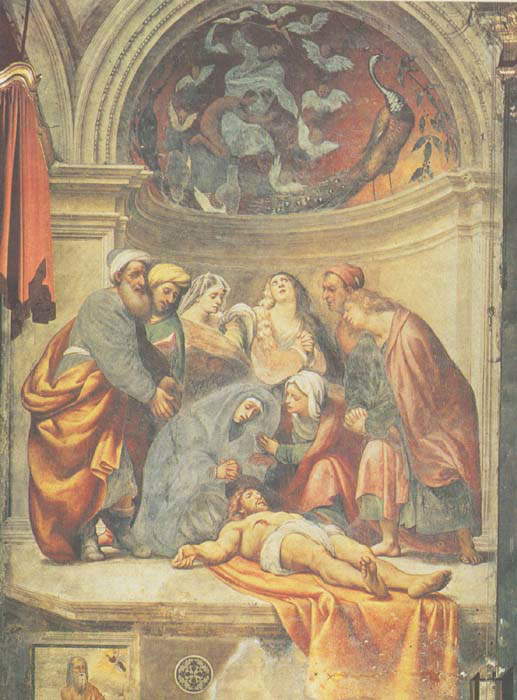

It proves much easier to list the artists who looked at Andrea Mantegna’s Dead Christ and drew inspiration for their art from it. The list is very long: the first to transpose Mantegna’s novelty, in all likelihood, was Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, better known as Sodoma (Vercelli, 1477 - Siena, 1549), who with his Lamentation over the Dead Christ in a private Milanese collection, executed around 1503, made an “outrageous homage to the perspective masterpieces” (Roberto Bartalini) of the great Venetian artist. And even in the 16th century there were several tributes to Mantegna’s masterpiece: mention must be made of the Deposition executed in fresco by Pordenone (real name Giovanni Antonio de’ Sacchis, Pordenone, 1483 - Ferrara, 1539) on the counter-façade of Cremona Cathedral, as well as the singular Dead Christ between Charity and Justice by Lelio Orsi (Novellara, 1511 - 1587), a small canvas preserved in Modena and made in the 1670s, and above all the Dead Christ with the Instruments of the Passion by Annibale Carracci (Bologna, 1560 - Rome, 1609), an early masterpiece of the Emilian painter, probably made around 1582-1584. Carracci’s work is particularly important in that it would be the first meditation on Mantegna to focus exclusively on the body of Christ: in particular, the Bolognese artist wanted to increase the tragic nature of Mantegna’s precedent by increasing the amount of blood, proposing an even more mangled body in a less dignified pose (Christ’s body is in fact bent at hip height), and with the objects of his martyrdom resting at his feet. The echo of Mantegna’s innovations reached as far as the seventeenth century: it was Orazio Borgianni (Rome, 1576 - 1616), an early Caravaggesque, who again included the mourners and gave an intimate and touching interpretation of the dead Christ, light years away from Carracci’s violence and pervaded by an atmosphere of sad melancholy, with the scene illuminated by a soft, dim light that softens Mantegna’s harshness while replicating the composition almost identically.

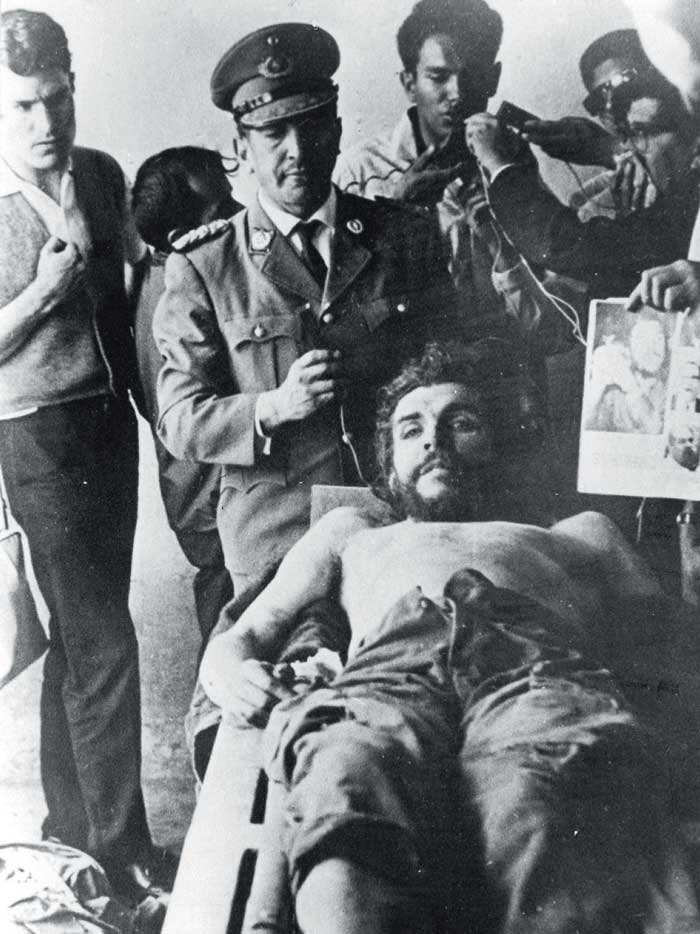

Centuries later, Mantegna has also provided suggestions for cinema. Beyond Pasolini’s Mamma Roma, where in the final scenes one witnesses the death of one of the protagonists (the very young Ettore who expires tied to a prison plank to the indifference of the guards) in which one wanted to see a reference to the dead Christ (denied, however, by Pasolini, who writing in the magazine Vie nuove addressed himself directly to Roberto Longhi, whose pupil he had been: “Ah, Longhi, you intervene, you explain, how it is not enough to put a foreshortened figure and look at it with the soles of the feet in the foreground to speak of Mantegna influence! But don’t these critics have eyes?”), other filmmakers have expressly taken inspiration from Mantegna’s painting to shoot some scenes in their films: among them it is possible to mention Paolo Benvenuti’s Il bacio di giuda (1988) and Andrej Zvjagincev’s Il ritorno (2003). In the field of photography, both the art critic and writer John Berger and the sociologist Eduard Grüner, in two of their essays ( Che Guevara dead and Iconografías malditas, respectively), have pointed to the Dead Christ as a reference to a famous 1967 photograph by Freddy Alborta depicting Che Guevara after his execution (Alborta’s work was moreover the focus of a 1997 documentary, El día que me quieras, directed by Leandro Katz).

|

| Sodom, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1503; oil on canvas; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Pordenone, Deposition (1520-1521; fresco; Cremona, Duomo) |

|

| Lelio Orsi, Dead Christ between Charity and Justice (c. 1570-1579; oil on canvas, 48 x 39.5 cm; Modena, Galleria Estense). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Annibale Carracci, Dead Christ and Instruments of the Passion (1583-1585; oil on canvas, 70.7 x 88.8 cm; Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart) |

|

| Orazio Borgianni, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1615; oil on canvas, 55 x 77 cm; Rome, Galleria Spada) |

|

| A still from the film Mamma Roma by Pier Paolo Pasolini |

|

| A still from the film The Kiss of Judas by Paolo Benvenuti |

|

| A frame from the film The Return by Andrei Zvjagincev |

|

| Cinematography by Freddy Alborta |

These are the last chapters of a long history that began with Ludovico Mantegna’s letter mentioned in the opening. Then, for at least three centuries, the vicissitudes of the painting become somewhat complex, and at a certain point in the story they split, because we know of a very similar replica, now in a private collection, so much so that there are passages in which the vicissitudes of the two canvases become confused. We know that the work, in 1531, was still among the possessions belonging to the Gonzaga: that year, a secretary of the Gonzaga court, Ippolito Calandra, wrote to Duke Frederick II that it was necessary to bring, to what would become the apartment of his wife, Margherita Paleologa (who would marry the duke in November 1531), at least six paintings, one of them “like that painting that el Mantegna did of that Christ who is in dark.” For seventy years, traces of the work were lost: it reappeared in 1603, listed in the inventory of paintings that the Roman cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini had acquired after the spoliations that followed the devolution of Ferrara to the Papal States (it seems, therefore, that at some point in history the Dead Christ had passed to the Este family). In 1626 the work appears in the inventory of Olimpia Aldobrandini’s collection, and for several decades it would remain in Rome. At the same time, a “N.S. deposto sopra il sepolcro in scurzo con cornici fregiate d’oro di mano del Mantegna” appears in the Gonzaga inventories in 1627: it is possible that this was the copy, which would later be sold in 1628, together with a large part of the Celeste Galeria (the spectacular Gonzaga collection) to Charles I of England, and then end up on the antiques market. The other specimen, however, remained in Rome until the early 19th century. On December 17, 1806, Giuseppe Bossi (Busto Arsizio, 1777 Milan, 1815), then secretary of the Brera Academy, wrote a letter to Antonio Canova asking for help in getting him his “desired Mantegna”: the sculptor actually helped his friend and bought the Dead Christ on the Roman market. The painting would later join the collections of the Pinacoteca, as did many other works in Bossi’s collection, later, in 1824 to be exact. It has not left the Milanese museum since then.

The subject of constant study, the focus of heated debate, and one of the most admired works in the Milanese museum, Andrea Mantegna’s Dead Christ is one of the cornerstones of the Renaissance, both technically and in terms of its content. Perhaps it is with this painting that for the first time all the fragility and all the humanity of Christ are emphasized and placed before the viewer’s eyes without delay. James Bradburne himself pointed this out at the presentation of the most recent exhibition: “Mantegna knew that more important than science and more important than perspective itself was to make Christ’s suffering visible, and to make his death absolute. To emphasize the humanity of Christ: if Christ had not been able to die, all the foundations of the Christian religion would have failed.” And Andrea Mantegna succeeded in this purpose with a canvas capable of shocking the history of art.

Reference bibliography

- Giovanni Agosti, Dominique Thiébaut (eds.), Mantegna 1431-1506, Officina Libraria, 2008

- Mauro Lucco (ed.), Mantegna in Mantova 1460-1506, exhibition catalog (Mantova, Palazzo Te, from September 16, 2006 to January 14, 2007), Skira, 2006

- Sergio Marinelli, Paola Marini, Mantegna and the Arts in Verona 1450-1500, exhibition catalog (Mantua, Palazzo Te, from September 16, 2006 to January 14, 2007), Marsilio, 2006

- Roberto Bartalini, Le Occasioni del Sodoma, Donzelli, 1996

- Claudia Cieri Via, Mantegna, Giunti, 1991

- Peter Humfrey, The Venetian Painting of the Renaissance at Brera, Cantini, 1990

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.