In the white courtyard of the Bishop’s Seminary in Senigallia, a group of young pretties chase each other, as if they wanted to fly, as if their black cloaks were wings. These images, which appear suspended, surreal, poetic and at the same time also a little disturbing, images that still challenge the viewer, are perhaps among the most famous of Italian photography. We are between 1961 and 1963, and Mario Giacomelli (Senigallia, 1925 - 2000), then a young, self-taught photographer, was making what would soon become one of his most famous and controversial series, Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto (I have no hands to caress my face). The series has always been the focus of exhibitions on Giacomelli, including even the major centennial retrospective, Mario Giacomelli. The Photographer and the Poet (in Milan, Palazzo Reale, May 22 to Sept. 7, 2025), curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi and Katiuscia Biondi Giacomelli, as part of which works from the photographer’s entire career were brought together: an entire room, defined by the curators as the “beating heart” of the exhibition, was dedicated precisely to Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto, a title that echoes a poem by Father David Maria Turoldo, chosen by the artist because it seemed to him the most suitable to convey, in a few words, the images of young seminarians.

The seminary in Senigallia was only a few kilometers from the home of the photographer, who was also born and raised in the Marche city. And it was there in that rigid and closed microcosm that Giacomelli would find the place to stage a series of seemingly carefree, willingly even bizarre photographs, but which actually conceal questions about the meaning of existence, faith, freedom, interrupted childhood and imposed vocation. For Giacomelli, Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto is a kind of existentialist reflection. The series, explains the photographer’s son, Simone Giacomelli, in the volume Mario Giacomelli. Works 1954-2000, “stems from reflections on the gap between worldly and ecclesial life, matured over time from the second half of the 1950s, talking with the young chaplain of his parish, the Church of Peace, touching in their reflections on the topics discussed by the Second Vatican Council in 1962.”

It was the chaplain of his parish, Fr. Enzo Formiconi, newly appointed rector of the seminary, who had introduced him to that silent world governed by rituals that seemed alien to contemporary reality. Giacomelli and Formiconi, moved by the spiritual and intellectual ferment that would soon animate the Second Vatican Council, shared a reflection: can the Church, in its most traditional form, still speak to the people of our time? And would those boys dressed in black, growing up far from the noise and temptations of the world, become free, conscious, happy men? It is a question that made sense in the 1960s; it is a question that is all the more pregnant with meaning even today, when more than sixty years have passed since Giacomelli took his photographs of pretenders.

However, Mario Giacomelli was not looking for answers, he was rather looking for new questions, and he found them, or rather let them surface, through photography. It is in this profoundly existential logic that the series fits, born after two years of reflection and immediately becoming the scene of a visual and poetic intuition that still prompts us to question ourselves decades later.

It must be said that photography, for Giacomelli, was neither chronicle nor document. It was total immersion in life. A way to “enter inside” things, to pass through them and return a vision that was never univocal, but made of layers, of time, of overlapping gazes. Thus, when in the 1960s Giacomelli began attending the Seminary, he did so with the humility and curiosity of someone who wanted to understand without invading. His approach, however, was visceral, never detached, and was nourished from the beginning by an urgency: that of confronting the meaning of religion, of pain, of salvation. With questions matured by talking at length with Fr. Formiconi.

Giacomelli thus entered the seminary thanks to the consent of Don Enzo himself, a man of faith but also of modernity, sensitive to the inner turmoil of an artist who wanted to observe, mingle, disturb. Before starting to shoot, however, it had been necessary to attend, distant but nevertheless present, later recounted in an interview, many years later (it was 1990), by the artist himself: “I would like to go inside. I believe in abstractionism, for me abstraction is a way to get even closer to reality. I am not so much interested in documenting what is happening as in going inside what is happening.” And it is, moreover, precisely the disturbance that becomes the engine and meaning of the series. The artist makes it clear: “I have finally disturbed the quiet of this convent,” which reads on the back of one print. Disturbing to understand, basically. Breaking the silence, to let the images speak. Even before he shoots, he spends months winning the trust of the boys, participating with them in prayers, lessons, playtime. When he finally picks up his camera, he is already part of the scene. He does not observe from the outside: he is an accomplice, an invisible director.

“The first few months,” says Simone Giacomelli, “he spent them gaining the confidence of the youngest, participating with them in educational, spiritual and playful activities. Soon he asked permission to bring his camera. He began photographing one Saturday in March 1961, during the meeting between the young students and their fathers. These were mostly farmers, hoping for a better future for their children. But in some cases, prevailing in the young seminarians was a painful sense of abandonment. Giving meaning to this photographic project was witnessing a scene. A father livid in the face, anger and shame barely restrained; and in front of him, his son in tears, wearing his Sunday best. The boy would rather have wrested the fruits from the earth for his own sustenance as his earthly father did, than speak to a Father they told him lived in Heaven, never showing himself, either for a slap or a hug. The boy was 11 years old.” That young man would have liked to stay on his land, to work, to live by the concreteness of toil and harvest. But he was shown another destiny, he would have to become a priest out of necessity, because his father, a farmer, wanted to tear him away from a life of misery, of working in the fields. Giacomelli would later confess to having photographed that moment, but not having had the courage to develop it. The fact remains that between the carnal father and the spiritual father (or rather: the Father, the one with a capital “P”) a void opened up, and in that void the artist grasped the trauma, the fracture, the enigma of existence that would run through the entire Pretini series. The final choice of the title, Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto (I have no hands to caress my face), stems as mentioned from a poem by Father David Maria Turoldo, a friend of Rector’s, and becomes the poetic key to the entire project: a cry of loneliness, but also a plea for love, an invocation.

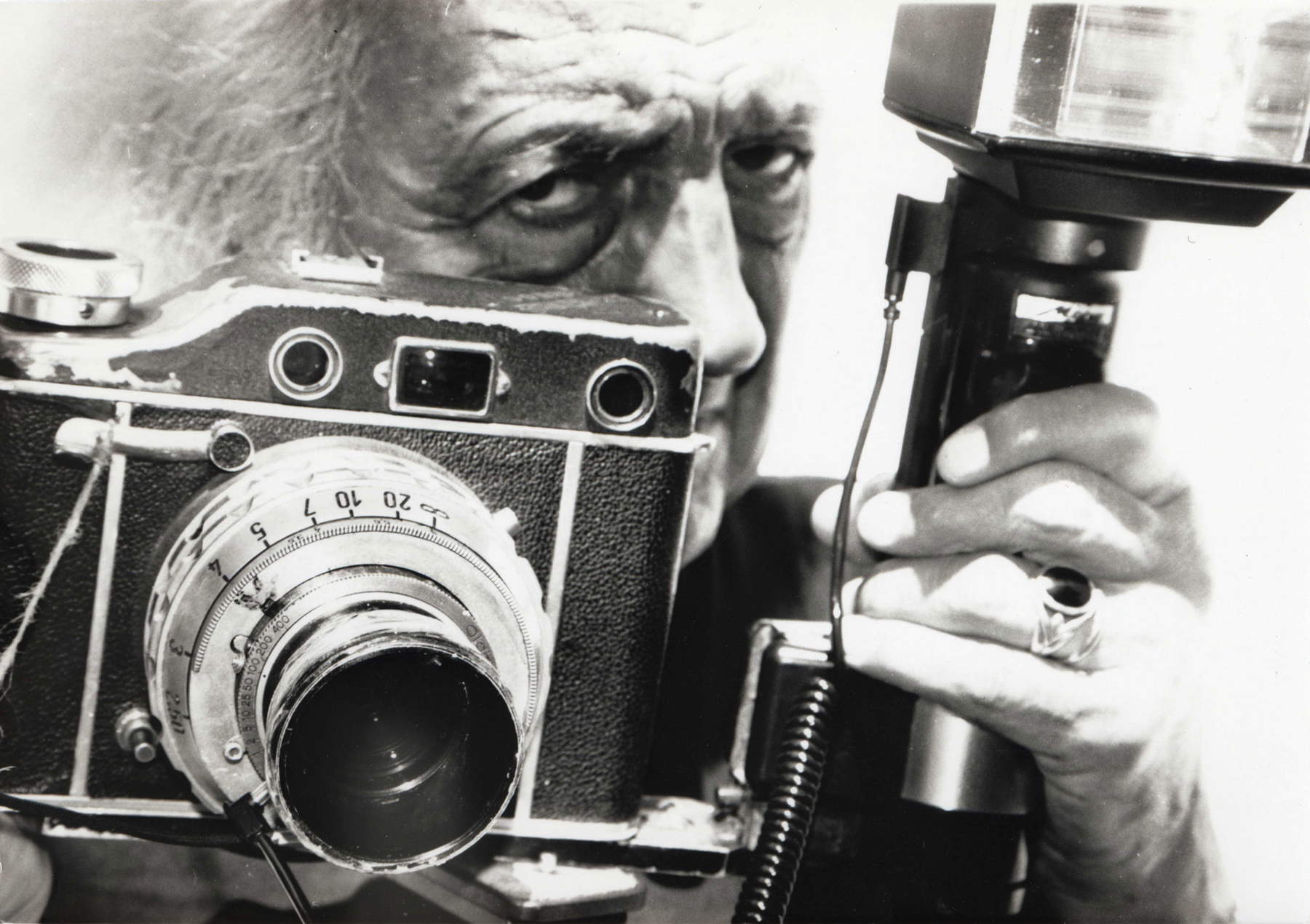

Famous on all the photographs in the series is the image of the circling of the pretenders. It was the rector himself who had suggested to the seminarians to make this roundabout, following Giacomelli’s directions, and the photographer, hidden in a skylight, photographed from above. “Iconic images these, of black figures suspended in white, obtained by masking in a darkroom by cutting out the silhouettes of the pretenders on the envelopes of photographic paper,” Simone Giacomelli writes again. “Everyone there knew that the gentleman with the camera would wreak havoc on the monotonous passage of time. Like when in the little ones’ dormitory, during the recitation of the rosary, he threw a pillow causing a pillow war; or when he brought from home his white cat with which the youngsters fell in love; or when he staged a little party in the seminary attic, with trumpet, piano and an empty wine bottle. In the winter, while one of them was helping the artist change the roll of film, Giacomelli set about throwing snowballs, thus instigating a battle in the middle of the white mantle that covered the courtyard around the seminary, while others with toboggans swooped down avoiding bodies specially arranged like dummies. Everyone followed the artist’s directives in a natural way, participating in the composition of those photographic scenes, which are now known all over the world.”

This is the strength of Giacomelli’s photographs. His subjects do not pose. Although there is careful direction behind the scene, each image is alive. The artist instigates, suggests, prepares. Then, in the darkroom, Giacomelli makes another transformation. The black silhouettes of the pretenders stand out against an almost unreal white, achieved through masking techniques that sculpt the figures and dissolve space. The result is a transfigured, suspended reality where the figures seem to fly, like birds. Photography thus becomes metaphor, and the images no longer narrate a seminar, but themes such as lost childhood, the tension between rule and desire, innocence and guilt, joy and at the same time the renunciation of worldly pleasures.

The images in the series, Giacomelli would later say in an interview granted Sept. 16, 1995, to journalist Francesca Vitale for the Radio Rai 3 program Lampi , “describe the moment of play, the transgression of the place where I photographed. I attended the seminar to understand what I could steal as a photographer with images, and I attended this place without knowing what I might want after all. Then later, almost in my third year of attending, I said to myself: ’Now I’m living in the light,’ because maybe I had it all wrong before, caught up in the whys of life, wondering all sorts of things about these pretenders (these priests who talk about how to raise children by not having children, how to keep a family together by not having a family, here I was expecting answers, which I didn’t get then, and rather I got caught up in thecourse of things), but then seeing them play, after reading Father Turoldo’s poem, with this new light, I discovered new images, spaces that were filled with imagination, like a little theater, like something that I did not know, and I began to know what was happening in front of my eyes. [...] The little pretenders on the meadow with the moving snow opening their black cloaks and they were suspended like birds in the white sky [...] To find myself in the seminary and see them playing, this circling, this looking like birds, this carefree, this anger that they were putting on me - me with the problems of life and them playing like children - out of this came all the whys. And my whiteness burned all traces of reality to propose a symbolic reality, basically they were signs and shapes as signs of something else. These things are images of memory, images that are born within us, things that I have experienced and continue to experience, I am also a spectator today.”

However, that whiteness, and especially that lightness, did not meet with unanimous approval. On the contrary: church authorities reacted with disappointment, accusing Giacomelli of ridiculing the figure of the seminarian, of debasing the cassock habit. The scandal then exploded when some images from the series, depicting young men holding cigars, won a contest sponsored by the German Cigar Consortium. At that point the case became national. Don Enzo was removed from the rectorship and sent to teach in Fano. And Giacomelli could no longer pass through the gates of the seminary.

By then, however, the work was done. And those images, rejected by those who felt they were offensive, are now part of the photographic heritage of the twentieth century. They speak to everyone, they force us to see with new eyes, and above all they are true not as document, but as poetry. Giacomelli, after all, was a poet with light and shadow, with his burnt whites and dissolving silhouettes. He was so with his gaze that could listen and record, with his ability to transform a snowy meadow into a stage of visions, a roundabout into a metaphor for the human condition.

Io non ho mani che mi accarezzino il volto (I have no hands to caress my face ) is an attempt to make the invisible visible, to “pass inside things,” as Giacomelli himself said, to talk about fragility, the desire to be loved, the tension between destiny and choice, perhaps even the need to disobey in order to exist. Giacomelli’s series, in a sense, is revolutionary because he wanted to show us what was really behind the cassock of a young boy who often became a priest out of necessity, out of compulsion, rather than out of choice or vocation: the flesh, the soul.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.