“Glück glaubte ein Gemälde so grossen Formats der Hand einer Frau nicht zutrauen zu dürfen.” That is, Glück did not believe that such a large-format painting was made by the hand of a woman. Writing these words was, in 1967, the then curator of the Painting Gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Günther Heinz (Salzburg, 1927 - Vienna, 1992). That year, the Austrian scholar had given the prints to an essay on Jan van den Hoecke and the Dutch painters in the Viennese museum, and he dwelt on a monumental painting, one of the most spectacular in the collection, a large oil on canvas two and seventy meters high by three and fifty-four meters wide, depicting a Triumph of Bacchus. The great protagonist of the work is the god of wine, visibly drunk, so much so that he cannot stand upright: he thus lies in a disheveled manner on top of a kind of wheelbarrow covered with a leopard skin, and pitifully pulled by a satyr who, far from being that cheerful and grotesque character we are used to seeing in works of the same subject, has rather the appearance of a dignified old man, who seems to turn a look of compassionate reproach on the young inebriated Bacchus. All around, a festive troop of various characters: there is Silenus, Bacchus’s companion, who is squeezing a bunch of grapes directly over the god’s mouth. Behind is Silenus’s donkey, on the opposite side is a bare-breasted maenad carrying a thyrsus with a few vine shoots entwined in it, and she is the only character looking toward the viewer, below still we observe three children playing with a goat (and one of them holds a glass, a kind of flûte), on the left another satyr playing a trumpet.

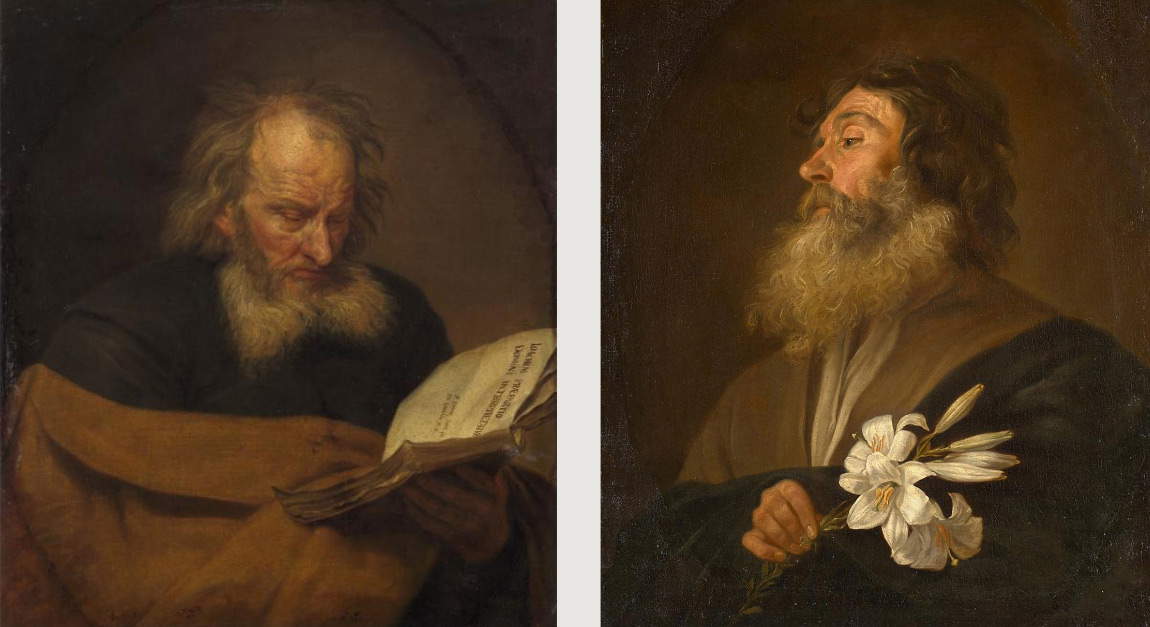

In addition to being a large painting, it is also an educated and up-to-date painting: we find in it suggestions from Rubens, revivals of ideas from Duquesnoy, Philippe de Champaigne, and Jordaens, classical quotations. And there is also an incredible rendering of the male anatomies: a sign that the artist who had created the work must have been remarkably familiar with the human body, and must have undergone continuous practice on real models. Scholars who had examined the Triumph of Bacchus before Heinz had thus discarded the hypothesis that it might be the work of a woman: too large, too complex, too beautiful, and too perfect for decades-old prejudices to assign it to a female hand. Consequently, the attribution in the 1659 inventory of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria (Wiener Neustadt, 1615 - Vienna, 1662) had always raised doubts: the Triumph of Bacchus, in fact, was recorded as the work of an unspecified “N. Woutiers.” Not even Gustav Glück (Vienna, 1871 - Santa Monica, 1952), historical director of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, and a great specialist in Dutch art, had been able to come up with convincing explanations as to the painting’s author. This was because, despite the fact that Michaelina’s name was already known in the 1960s, Glück, as Heinz reported, did not believe that that work could have been done by a female hand. It had therefore taken Heinz’s insight to realize that that large canvas was instead the work of a woman: Michaelina Wautier (Mons, 1617 - Brussels, 1689). And to think that the answer had always been close at hand: in the same museum, in fact, a St. Joachim is preserved along with its pendant, a St. Joseph, both also once in the archduke’s collection. Behind the St. Joachim appears the artist’s signature: Michelline Wovteers.F., which stands for “Michaelina Wautier fecit,” or “Michaelina Wautier painted it” (“Wautier” is the French form of the Flemish “Woutiers”). By closely comparing the two saints with the Triumph of Bacchus, Heinz had noticed that “the characteristic ductus is so clearly corresponding, that these works can be recognized, even without outside help, as products of the same hand.” And stylistically, too, the similarities are indisputable: one need only compare the heads of the saints and their naturalism with the satyr pushing Bacchus’ wheelbarrow to see that there is perfect consistency.

However, despite the fact that Heinz’s attribution was matched (and no one has since questioned that Michaelina painted the Triumph of Bacchus), it was not easy for the Flemish artist to leap to the attention of the general public. Until the 2000s, her monumental painting remained confined to a section of the Kunsthistorisches Museum not open to the public. Then, the growing interest of scholars, culminating in 2005 with the first attempt to compile a general catalog of Michaelina, brought the Triumph of Bacchus out of oblivion: for the first time, a wide public was able to see the work, and this was on the occasion of the exhibition entitled Sinnlich, weiblich, flämisch (“Sensual, Feminine, Flemisch”) dedicated to women painted by Rubens and contemporaries and opened at the Viennese museum on August 6, 2009. Michaelina’s painting was a huge success, between 2013 and 2014 it underwent a restoration conducted by Michael Odlozil, and, at the initiative of scholar Gerlinde Gruber, curator of the section of Flemish Baroque painting at the Kunsthistorisches, and thanks to the mediation of Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, director of the Austrian museum’s Gemäldegalerie, the Triumph of Bacchus was finally able to make its entrance, after the restoration was completed, into the main section of the institution, and specifically into the Rubens room.

|

| Michaelina Wautier, Triumph of Bacchus (1659; oil on canvas, 270 x 354 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

|

| Models for the Triumph of Bacchus. Left to right: Roman Art, copy from Greek original, Wounded Amazon (c. 450 B.C.; marble; New York, Metropolitan Museum); Pieter Paul Rubens, Bacchus on a Wine Barrel (c. 1638-1640; oil on canvas, 191 x 161.3 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage); Da Jacob Jordaens, Bacchanal (c. 1650; oil on canvas, 157 x 100 cm; Le Puy, Musée Crozatier) |

|

| François Duquesnoy, Sleeping Silenus (c. 1630?; bronze and lapis lazuli, 53 x 105 cm; Antwerp, Rubenshuis) |

|

| Philippe de Champaigne, Adam and Eve Mourn the Death of Abel (1656; oil on canvas, 312 x 394 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

|

| Michaelina Wautier, St. Joachim and St. Joseph (both before 1659; oil on canvas, 76 x 66 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

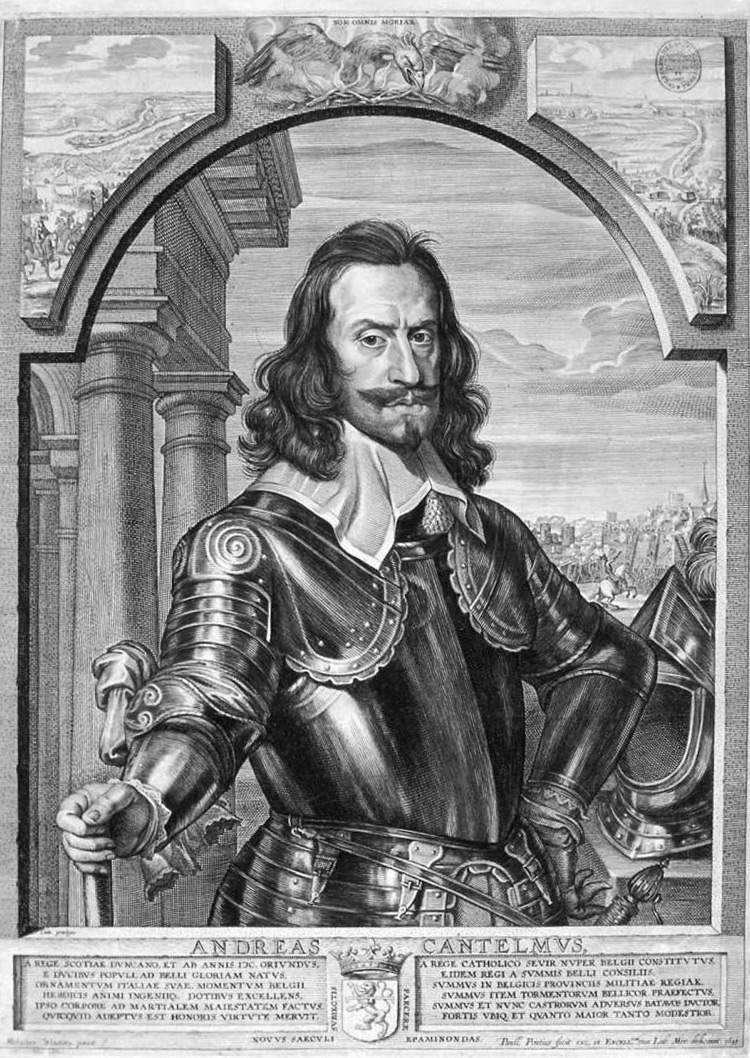

About Michaelina, however, we continue to have little information, without calculating the fact that her known works are very few in number. Despite the fact that the painter lived for seventy-two years, her entire artistic career, at present, can be placed in a very specific time frame: between 1643 and 1659. Before and after these dates, there are no known works, nor are there any others that, by style, can be dated outside this period. Art historian Katlijne van der Stighelen, a great expert on Michaelina Wautier, speculates that the painter began her career as a portrait painter-a fact that “is not surprising,” the scholar explains in the catalog of the first monographic exhibition devoted to the artist (at the Museum aan de Stroom and the Rubenshuis in Antwerp, June 1 to September 2, 2018), because “women with artistic ambitions” at the time “preferred to focus on portraiture.” “there was never a shortage of subjects (starting with members of one’s own family), and knowledge of anatomy was not a prerequisite for capturing an accurate likeness.” It follows that Michaelina’s earliest known works are portraits. Even, her earliest work that can be dated with certainty has not even reached us, since it arrived reproduced in an engraving made by Paulus Pontius (Antwerp, 1603 - 1658). It is a portrait depicting the leader Andrea Cantelmo (Pettorano, 1598 - Alcubierre, 1645), commander of the Spanish armies during the Thirty Years’ War and the War of Succession of Mantua and Monferrato.

We are not sure how Michaelina might have come into contact with Andrea Cantelmo: we can speculate, however, that the Wautier family had solid contacts with the Neapolitan communities living in Flanders (contacts that, moreover, may have also benefited the artist in bringing his style up to date with the achievements of Neapolitan painting of the time: certain of Michaelina’s saints show connections, for example, with the art of José de Ribera). Michaelina’s father, Charles Wautier, had been part of theentourage of Pedro Enríquez de Acevedo y Toledo, count of Fuentes and governor of the Spanish Low Countries between 1596 and 1599, and in this context the family may have come into connection with several members of the Neapolitan circles active in Flanders (as is well known, both Naples and Flanders were dependent on Spain at the time). What is certain is that Michaelina came from a wealthy family: her father had been a court page as a young man and later probably became an officer in the Spanish army stationed in Flanders, while her mother, Jeanne George, came from a wealthy merchant family. Although no one in the family harbored artistic interests, it is nevertheless certain that such an environment could provide important support to Michaelina during the start of her artistic activity, toward which she was probably driven by personal interest: perhaps, her knowledge of the works of Anna Francisca de Bruyns (Morialmé, 1604 - Arras, 1675), who in 1628 was present and active in Mons, Michaelina’s hometown, influenced her decision to become a painter. In any case, she was the first artist in the family, along with her younger brother Charles (Mons, 1609 - Brussels, 1703), who embarked on an artistic career in parallel with her (although we do not know which of the two began first).

The above-mentioned portrait of Andrea Cantelmo, in all likelihood, helped to pave, for her who was in any case an already mature artist (one would not otherwise explain where a work of such great quality as the portrait of the Abruzzese condottiere came from), the road to the most important circles in Flanders at the time. Another portrait, dated 1646, depicting a Spanish army commander, whose identity, however, is unknown, is the oldest surviving painting of Michaelina. Taken in three-quarter view, the man shows a confident gaze that does not meet the viewer’s eyes and is brought to life by the light coming from the right, illuminating his rosy complexion and making the commander’s figure stand out against the dark background. The clothes are those typical of the time (the fashion of the collar to be tightened with the two tassels was proper to the 1740s) and are those of a military man: in particular, the leather jacket that the figure wears was the one that soldiers used to wear under their armor. It is a vivid, very precise portrait, adhering to the truth, revealing manners typical of a virtuoso of the brush (let us dwell on the details: the light that makes the eyes shine, the curls of the wavy hair, the mustache, the lace that decorates the pink sash, but also the gaze that reveals an attention to the rendering of the subject’s personality) and demonstrating the pure and obvious talent of Michaelina Wautier.

|

| Paulus Pontius da Michaelina Wautier, Portrait of Andrea Cantelmo (1643; engraving on paper, 403 x 298 mm; Private collection) |

|

| Michaelina Wautier, Portrait of a Spanish Army Commander (1646; oil on canvas, 63 x 56.5 cm; Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts) |

An interesting fact that emerges from Michaelina’s works is her ability to deal fluently and confidently with male models: this was especially seen in the Triumph of Bacchus, a work in which the artist paints with extreme skill the nude bodies of men of all ages. The painter’s exceptional skill in depicting men denotes a great confidence with male subjects, stemming from the fact that Michaelina had the opportunity to draw while observing real, living, flesh-and-blood models: as far as we know, hers is a very rare case, probably unique, in all of northern Europe in the seventeenth century. Women were not allowed to try their hand at real models: this issue was still debated in nineteenth-century Brussels, when it had to be determined whether women could enter the Academy to practice on nude models. Michaelina had already solved this problem in the seventeenth century. Surely she had her brother Charles to thank: indeed, it was together with him that Michaelina could paint looking at nude men. Admittedly, we have little information about the collaboration between the two brothers: we do not know how their workshop was structured, what exactly their relationships were, how they divided their work if they worked together. We can speculate, however, that they shared a studio, or at least worked in the same building: the fact that Charles worked closely with her certainly allowed her to do basically whatever she wanted, in defiance of the rigid morals of the time, according to which it was unthinkable that a woman could be left alone in front of a model.

However, the collaboration with Charles also provided Michaelina with other important insights. Indeed, Charles, from the very beginnings of his career, displayed a marked Caravaggism (so much so that we still wonder whether or not he had been to Italy, and if so whether Michaelina accompanied him): a Caravaggism that may also have influenced his sister herself. But the “mediator” may also have been a profoundly Caravaggesque painter, active in the Brussels of the time: we are talking about Theodoor van Loon (Erkelenz, 1581/1582 - Maastricht, 1649), present in Italy between 1602 and 1608, precisely in the years in which Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) first established himself, and then began his own downward parabola, which ended in 1610 with his untimely death. A work like the splendid Education of the Virgin, from 1656, is a kind of summation of these experiences. In the painting, a very young Mary, astonishing in her extraordinary verisimilitude, made all the more precious by her vivacity (her viscous gaze, the corners of her mouth hinting at a smile, her posture), is held by the hand of her mother, St. Anne, who helps her in the task of learning to read from a book. St. Joachim, Mary’s father, is caught in an ecstatic attitude, as is typical of the iconography of works that insist on the subject of the Virgin’s education: since the little girl was born through divine intervention (and since, moreover, she was born without sin and should have given birth to Jesus), the figure of Joachim usually has the purpose of making evident this thread that unites his family to God.

TheVirgin’s Education is a cultured work, cast in the cultural context of the time: as van der Stighelen suggests, the fact that Anne follows Mary so intensely as the girl learns to read may be a kind of homage to the ideas of the humanist Juan Luis Vives (Valencia, 1492 - Bruges, 1540), a Spaniard but who moved to Flanders at a very young age to escape the Inquisition in his country. Vives was in fact a staunch advocate of female education, and although he still considered women subordinate to men, in his De institutione feminae christianae (considered by many to be the main treatise of the sixteenth century on the subject of female education) Vives suggested that women should learn to read (even though the purpose of reading, for Vives, was the preservation of the Christian virtues, from humility to chastity, from sincerity to moderation). In addition to its content, the painting, now held in a private collection, is interesting for several other reasons, starting with its obvious Caravaggism, as anticipated above: the characters are characterized by remarkable realism and the figures are constructed by means of light, which creates intense chiaroscuro effects. The very young scholar Hannelore Magnus wanted to identify in two paintings by van Loon some precedents that could have inspired Michaelina: the face of St. Anne resembles that of the midwife who appears in van Loon’s Birth of the Virgin preserved in the basilica of Our Lady in Scherpenheuvel, and the pose of Joachim is practically identical to that of the St. Simeon we find in the Presentation in the Temple, another painting by van Loon preserved in the same house of worship. Debts to van Loon can, moreover, be found in other paintings as well: this is the case with Michaelina’s last known work, theAnnunciation dated 1659. Here, the great plasticism of the figures of the protagonists, as well as some compositional solutions (the archangel Gabriel arriving proceeding on a cloud, the Virgin kneeling with her gaze low and seeming almost to shield herself, the rays of light that, almost like thunderbolts, rend the clouds) derive from a painting of the same subject made by van Loon and preserved in Brussels. Returning instead to theEducation of the Virgin, Michaelina’s painting is also distinguished by the signature the artist placed on it. On the column, in fact, it reads this phrase: Michaelina Wautier, invenit, et fecit 1656 (“Michaelina Wautier conceived and made [the painting] in 1656”), a formula that the artist had moreover already used in the past. It is almost a stance, a proud vindication, a declaration of her own talent: Michaelina wanted to emphasize that she did not merely paint the work, but that she also conceived it, that the composition was the fruit of her own thought, and that she was able to elaborate the theme with originality, an all-female originality that the painter intends to manifest with pride and dignity.

And Michaelina was able to give substance to her originality in a great variety of subjects: her versatility allowed her to deal with paintings of religious subjects, mythological paintings, portraits, still lifes, and genre scenes with equal success. For example, a tasty painting preserved in the Seattle Art Museum that depicts two children intent on playing with soap bubbles belongs to the latter strand. This was a particularly popular subject in seventeenth-century northern Europe, partly because of its allegorical implications (the soap bubble, due to its ephemeral nature, is a symbol of vanitas): Michaelina knew how to deal with it by giving the scene a tone of intimate everyday life and producing, writes van der Stighelen, two “beautifully painted figures,” with the faces being “executed with a fluid impasto technique, and with the dark-haired child modeled so expressively, so much so as to look like he came out of a youthful painting by Caravaggio.” From her production, finally, there was no lack of the genre of theself-portrait: we have a wonderful and self-conscious one, preserved in a private collection, in which Michaelina portrays herself intent on painting, in front of a canvas resting on an easel. Her pride is reminiscent of that of a Sofonisba Anguissola, an Elisabetta Sirani or an Artemisia Gentileschi (for that matter, it is certain that Michaelina was familiar with Italian art, and perhaps even got to know a self-portrait of Artemisia, in the form of an engraving), as opposed to her fellow countrymen Rubens van Dyck, and Jordaens he avoids including in the self-portrait signs of the status he achieved through painting, but merely portrays himself with the tools of the trade, and again proudly includes a clock in the composition (we see it resting on the top of the easel), as if to say, perhaps, that his art will survive over time.

|

| Michaelina Wautier, The Education of the Virgin (1656; oil on canvas, 144.7 x 119.4 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Left: Theodoor van Loon, Presentation in the Temple (c. 1623-1628; oil on canvas, 257 x 180 cm; Scherpenheuvel, Basilica of Our Lady). Right: Theodoor van Loon, Birth of the Virgin (c. 1623-1628; oil on canvas, 257 x 180 cm; Scherpenheuvel, Basilica of Our Lady) |

|

| Michaelina Wautier, Annunciation (1659; oil on canvas, 200 x 134 cm; Louveciennes, Musée-promenade de Marly-le-Roi) |

|

| Michaelina Wautier, Two Children Playing with Soap Bubbles (c. 1653; oil on canvas, 90.5 x 121.3 cm; Seattle, Seattle Art Museum) |

|

| Michaelina Wautier, Self-Portrait (c. 1650; oil on canvas, 120 x 102 cm; Private collection) |

|

| From left to right: Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait (1554; oil on panel, 19.5 x 14.5 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum); Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as Allegory of Painting (c. 1638-1639; oil on canvas, 98.6 x 75.2 cm; Windsor, The Royal Collection); Elisabetta Sirani, Self-Portrait as Allegory of Painting (1658; oil on canvas, 114 x 85 cm; Moscow, Pushkin Museum) |

And now there are indeed all the conditions for Michaelina Wautier’s art to truly survive, finally emerging from the darkness of history and ready to be rediscovered. Indeed, her works remained, for centuries, hidden from the eyes of most: most of them figured in family collections after her passing, and the private circulation of such paintings prevented Michaelina from enjoying wide recognition. Her name therefore took to flow karstically among inventories, catalogs and collections, often with different variants, until it began to arouse some interest, resulting, in 1884, in the first essay on the artist, written by a near-homonym of Michaelina, Alphonse-Jules Wauters (Brussels, 1845 - 1916), an art historian and lecturer at the Royal Academy of Belgium, who had come across the talented painter’s works simply by leafing through a Kunsthistorisches Museum catalog, published in that same 1884. This, too, was a work of primary importance for the rediscovery of Michaelina: for the first time, it was established that the St. Joseph and St. Joachim discussed above were not, as was then believed, paintings by Frans Wouters, a pupil of Rubens, but were works by Michaelina. Wauters’ article stimulated some curiosity, although contributions on Michaelina had continued to follow one another with some sporadicity, and it took Heinz’s intervention, discussed in the opening, to restore the artist to her greatness once again.

This path of rediscovery culminated with the major monographic exhibition in Antwerp in 2018, curated precisely by Katlijne van der Stighelen, who so much of her career has been devoted to reconstructing Michaelina’s affairs. Of course: many unanswered questions remain, because we still know little about Michaelina, her life and career, and probably many works have yet to emerge. But it can be said that the latest achievements in the field of studies on her figure have restored her to the pantheon of the greats of Flemish painting, and today her name can be safely placed alongside that of male colleagues such as Rubens, van Dyck, Jordaens, Snyders, Sweerts. To whom he had nothing to envy.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.